ELEMENTARY CONCEPTS OF VECTOR ALGEBRA

In physics, some quantities possess only magnitude and some quantities possess both magnitude and direction. To understand these physical quantities, it is very important to know the properties of vectors and scalars.

Scalar

It is a property which can be described only by magnitude. In physics a number of quantities can be described by scalars.

Examples

Distance, mass, temperature, speed and energy.

Vector

It is a quantity which is described by both magnitude and direction. Geometrically a vector is a directed line segment which is shown in Figure 2.10. In physics certain quantities can be described only by vectors.

Figure 2.10 Geometrical representation of a vector

Examples Force, velocity, displacement, position vector, acceleration, linear momentum and angular momentum.

Magnitude of a Vector

The length of a vector is called magnitude of the vector. It is always a positive quantity. Sometimes the magnitude of a vector is also called ‘norm’ of the vector. For a vector A, the magnitude or norm is denoted by |A| or simply ‘A’ (Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11 Magnitude of a vector

Different types of Vectors

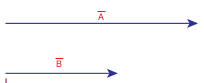

- Equal vectors: Two vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) are said to be equal when they have equal magnitude and same direction and represent the same physical quantity (Figure 2.12.).

Figure 2.12 Geometrical representation of equal vectors

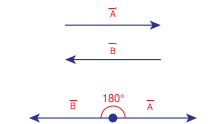

(a)Collinear vectors: Collinear vectors are those which act along the same line. The angle between them can be 0° or 180°.

(i) Parallel Vectors: If two vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) act in the same direction along the same line or on parallel lines, then the angle between them is \(0^{\circ}\) (Figure 2.13).

Figure 2.13 Geometrical representation of parallel vectors

(ii) Anti–parallel vectors: Two vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) are said to be anti-parallel when they are in opposite directions along the same line or on parallel lines. Then the angle between them is \(180^{\circ}\) (Figure 2.14).

Figure 2.14 Geometrical representation of anti– parallel vectors.

- Unit vector: A vector divided by its magnitude is a unit vector. The unit vector for \(\vec{A}\) is denoted by \(\hat{A}\) (read as A cap or \(\mathrm{A}\) hat). It has a magnitude equal to unity or one.

$$ \text { Since, } \hat{A}=\frac{\vec{A}}{A} \text { we can write } \vec{A}=A \hat{A} $$

Thus, we can say that the unit vector specifies only the direction of the vector quantity.

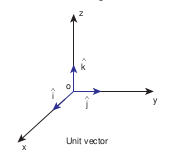

3. Orthogonal unit vectors: Let \(\hat{i}, \hat{j}\) and \(\hat{k}\) be three unit vectors which specify the directions along positive \(x\) -axis, positive \(y\) -axis and positive \(z\) -axis respectively. These three unit vectors are directed perpendicular to each other, the angle between any two of them is \(90^{\circ}. \hat{i}, \hat{j}\) and \(\hat{k}\) are examples of orthogonal vectors. Two vectors which are perpendicular to each other are called orthogonal vectors as is shown in Figure 2.15

Figure 2.15 Orthogonal unit vectors

Addition of Vectors

Since vectors have both magnitude and direction they cannot be added by the method of ordinary algebra. Thus, vectors can be added geometrically or analytically using certain rules called ‘vector algebra’. In order to find the sum (resultant) of two vectors, which are inclined to each other, we use (i) Triangular law of addition method or (ii) Parallelogram law of vectors.

Triangular Law of addition method

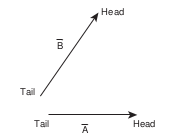

Let us consider two vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) as shown in Figure 2.16.

\(\overrightarrow{O Q} = \overrightarrow{O P} + \overrightarrow{P Q}\)

figure 2.16 Head And Tail Of The Vectors

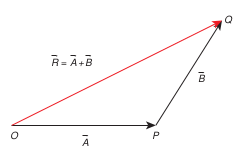

To find the resultant of the two vectors we apply the triangular law of addition as follows:

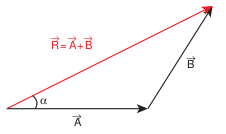

Represent the vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) by the two adjacent sides of a triangle taken in the same order. Then the resultant is given by the third side of the triangle taken in the reverse order as shown in Figure 2.17.

\(\overrightarrow{O Q} = \overrightarrow{O P} + \overrightarrow{P Q}\)

Figure 2.17 Triangle law of addition

To explain further, the head of the first vector \(\vec{A}\) is connected to the tail of the second vector \(\vec{B}\) . Let \(\theta\) be the angle between \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) . Then \(\vec{R}\) is the resultant vector connecting the tail of the first vector \(\vec{A}\) to the head of the second vector \(\vec{B}\) . The magnitude of \(\vec{R}\) (resultant) is given geometrically by the length of \(\vec{R}\) (OQ) and the direction of the resultant vector is the angle between \(\vec{R}\) and \(\vec{A}\) . Thus we write \(\vec{R}=\vec{A}+\vec{B}\) .

\(\overrightarrow{O Q}=\overrightarrow{O P}+\overrightarrow{P Q}\)(1) Magnitude of resultant vector The magnitude and angle of the resultant vector are determined as follows.

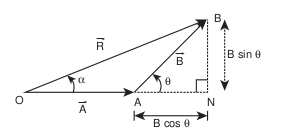

From Figure 2.18, consider the triangle \(\mathrm{ABN}\) , which is obtained by extending the side \(\mathrm{OA}\) to \(\mathrm{ON}\) . \(\mathrm{ABN}\) is a right angled triangle.

Figure 2.18 Resultant vector and its direction by triangle law of addition.

From Figure 2.18

\(\begin{gathered} \cos \theta=\frac{A N}{B} \therefore A N=B \cos \theta \text { and } \\ \sin \theta=\frac{B N}{B} \therefore B N=B \sin \theta \end{gathered}\)For \(\triangle O B N\) , we have \(O B^{2}=O N^{2}+B N^{2}\)

\(\begin{aligned} & \Rightarrow R^{2}=(A+B \cos \theta)^{2}+(B \sin \theta)^{2} \\ & \Rightarrow R^{2}=A^{2}+B^{2} \cos ^{2} \theta+2 A B \cos \theta+B^{2} \sin ^{2} \theta \\ & \Rightarrow R^{2}=A^{2}+B^{2}\left(\cos ^{2} \theta+\sin ^{2} \theta\right)+2 A B \cos \theta \\ & \Rightarrow R=\sqrt{A^{2}+B^{2}+2 A B \cos \theta} \end{aligned}\)which is the magnitude of the resultant of \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\)

(2) Direction of resultant vectors: If \(\theta\) is the angle between \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) , then

\(|\vec{A}+\vec{B}|=\sqrt{A^{2}+B^{2}+2 A B \cos \theta}\)If \(\vec{R}\) makes an angle a with \(\vec{A}\) , then in \(\triangle \mathrm{OBN}\) ,

\(\begin{aligned} & \tan \alpha=\frac{B N}{O N}=\frac{B N}{O A+A N} \\ & \tan \alpha=\frac{B \sin \theta}{A+B \cos \theta} \\ & \Rightarrow \alpha=\tan ^{-1}\left(\frac{B \sin \theta}{A+B \cos \theta}\right) \end{aligned}\)EXAMPLE 2.1

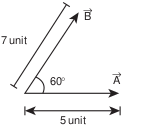

Two vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) of magnitude 5 units and 7 units respectively make an angle \(60^{\circ}\) with each other as shown below. Find the magnitude of the resultant vector and its direction with respect to the vector \(\vec{A}\) .

Solution

By following the law of triangular addition, the resultant vector is given by

\(\vec{R}=\vec{A}+\vec{B}\)as illustrated below

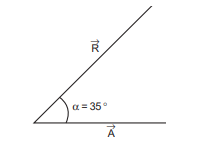

The angle \(\alpha\) between \(\vec{R}\) and \(\vec{A}\) is given by

\(\tan \alpha=\frac{B \sin \theta}{A+B \cos \theta}\)

Note Another method to determine the resultant and angle of resultant of two vectors is the Parallelogram Law of vector addition method. It is given in appendix 2.1

Subtraction of vectors

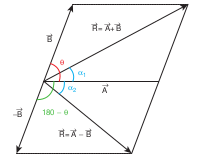

Since vectors have both magnitude and direction two vectors cannot be subtracted from each other by the method of ordinary algebra. Thus, this subtraction can be done either geometrically or analytically. We shall now discuss subtraction of two vectors geometrically using the Figure 2.19

For two non-zero vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) which are inclined to each other at an angle \(\theta\) , the difference \(\vec{A}-\vec{B}\) is obtained as follows. First obtain \(-\vec{B}\) as in Figure 2.19. The angle between \(\vec{A}\) and \(-\vec{B}\) is \(180-\theta\) .

Figure 2.19 Subtraction of vectors

The difference \(\vec{A}-\vec{B}\) is the same as the resultant of \(\vec{A}\) and \(-\vec{B}\) .

We can write \(\vec{A}-\vec{B}=\vec{A}+(-\vec{B})\) and using the equation (2.1), we have

\(|\vec{A}-\vec{B}|=\sqrt{A^{2}+B^{2}+2 A B \cos (180-\theta)}\)Since, \(\cos (180-\theta)=-\cos \theta\) , we get

\(\Rightarrow|\vec{A}-\vec{B}|=\sqrt{A^{2}+B^{2}-2 A B \cos \theta}\)Again from the Figure 2.19, and using an equation similar to equation (2.2) we have

\(\tan \alpha_{2}=\frac{B \sin \left(180^{\circ}-\theta\right)}{A+B \cos \left(180^{\circ}-\theta\right)}\)But \(\sin \left(180^{\circ}-\theta\right)=\sin \theta\) hence we get

\(\Rightarrow \tan \alpha_{2}=\frac{B \sin \theta}{A-B \cos \theta}\)Thus the difference \(\vec{A}-\vec{B}\) is a vector with magnitude and direction given by equations 2.4 and 2.6 respectively.

EXAMPLE 2.2

Two vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) of magnitude 5 units and 7 units make an angle \(60^{\circ}\) with each other. Find the magnitude of the difference vector \(\vec{A}-\vec{B}\) and its direction with respect to the vector \(\vec{A}\) . Solution

Using the equation (2.4),

\(\begin{aligned} & |\vec{A}-\vec{B}|=\sqrt{5^{2}+7^{2}-2 \times 5 \times 7 \cos 60^{\circ}} \\ & =\sqrt{25+49-35}=\sqrt{39} \text { units } \end{aligned}\)The angle that \(\vec{A}-\vec{B}\) makes with the vector \(\vec{A}\) is given by

\(\begin{gathered} \tan \alpha_{2}=\frac{7 \sin 60^{\circ}}{5-7 \cos 60^{\circ}}=\frac{7 \sqrt{3}}{10-7}=\frac{7}{\sqrt{3}}=4.041 \\ \alpha_{2}=\tan ^{-1}(4.041) \cong 76^{\circ} \end{gathered}\)