CONCEPT OF REST AND MOTION

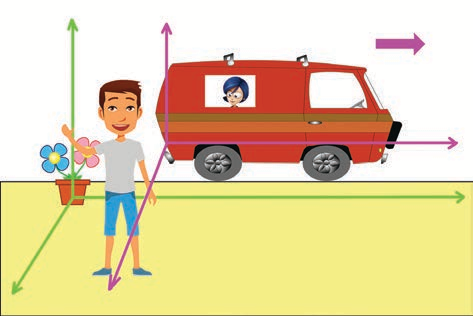

The concept of rest and motion can be well understood by the following elucidation (Figure 2.1). A person sitting in a moving bus is at rest with respect to a fellow passenger but is in motion with respect to a person outside the bus. The concepts of rest and motion have meaning only with respect to some reference frame. To understand rest or motion we need a convenient fixed reference frame.

Figure 2.1 Frame of Reference

Frame of Reference:

If we imagine a coordinate system and the position of an object is described relative to it, then such a coordinate system is called “Cartesian coordinate system” as shown in Figure 2.2 At any given instant of time, the frame of reference with respect to which the position of the object is described in terms of position coordinates (x, y, z) (i.e., distances of the given position of an object along the x, y, and z–axes.) is called “Cartesian coordinate system” as shown in Figure 2.2

Figure 2.2 Cartesian coordinate system

It is to be noted that if the x, y and z axes are drawn in anticlockwise direction then the coordinate system is called as “right– handed Cartesian coordinate system”. Though other coordinate systems do exist, in physics we conventionally follow the right–handed coordinate system as shown in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Right handed coordinate system

The following Figure 2.4 illustrates the difference between left and right handed coordinate systems.

Figure 2.4 Right and left handed coordinate systems

Point mass

To explain the motion of an object which has finite mass, the concept of “point mass” is required and is very useful. Let the mass of any object be assumed to be concentrated at a point. Then this idealized mass is called “point mass”. It has no internal structure like shape and size. Mathematically a point mass has finite mass with zero dimension. Even though in reality a point mass does not exist, it often simplifies our calculations. It is to be noted that the term “point mass” is a relative term. It has meaning only with respect to a reference frame and with respect to the kind of motion that we analyse.

Examples

-

To analyse the motion of Earth with respect to Sun, Earth can be treated as a point mass. This is because the distance between the Sun and Earth is very large compared to the size of the Earth.

-

If we throw an irregular object like a small stone in the air, to analyse its motion it is simpler to consider the stone as a point mass as it moves in space. The size of the stone is very much smaller than the distance through which it travels.

Types of motion

In our day‒to‒day life the following kinds of motion are observed: a) Linear motion An object is said to be in linear motion if it moves in a straight line.

Examples

- An athlete running on a straight track

- A particle falling vertically downwards to the Earth.

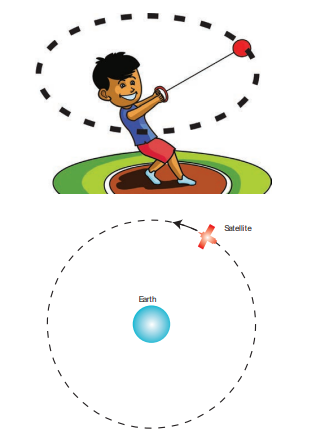

b) Circular motion Circular motion is defined as a motion described by an object traversing a circular path.

Examples

- The whirling motion of a stone attached to a string

- The motion of a satellite around the Earth

These two circular motions are shown in Figure 2.5

Figure 2.5 Examples of circular motion

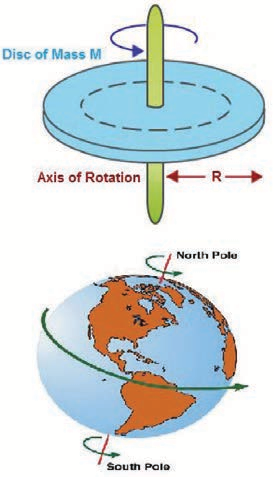

c) Rotational motion If any object moves in a rotational motion about an axis, the motion is called ‘rotation’. During rotation every point in the object transverses a circular path about an axis, (except the points located on the axis).

Examples

- Rotation of a disc about an axis through its centre

- Spinning of the Earth about its own axis.

These two rotational motions are shown in Figure 2.6.

Figure 2.6 Examples of Rotational motion

d) Vibratory motion If an object or particle executes a to–and– fro motion about a fixed point, it is said to be in vibratory motion. This is sometimes also called oscillatory motion.

Examples

- Vibration of a string on a guitar

- Movement of a swing

These motions are shown in Figure 2.7

Figure 2.7 Examples of Vibratory motion

Other types of motion like elliptical motion and helical motion are also possible.

Motion in One, Two and Three Dimensions

Let the position of a particle in space be expressed in terms of rectangular coordinates x, y and z. When these coordinates change with time, then the particle is said to be in motion. However, it is not necessary that all the three coordinates should together change with time. Even if one or two coordinates change with time, the particle is said to be in motion. Then we have the following classification.

(i) Motion in one dimension

One dimensional motion is the motion of a particle moving along a straight line.

This motion is sometimes known as rectilinear or linear motion.

In this motion, only one of the three rectangular coordinates specifying the position of the object changes with time.

For example, if a car moves from position A to position B along x–direction, as shown in Figure 2.8, then a variation in x–coordinate alone is noticed.

Figure 2.8 Motion of a particle along one dimension

Examples

- Motion of a train along a straight railway track.

- An object falling freely under gravity close to Earth.

(ii) Motion in two dimensions

If a particle is moving along a curved path in a plane, then it is said to be in two dimensional motion.

In this motion, two of the three rectangular coordinates specifying the position of object change with time.

For instance, when a particle is moving in the y – z plane, x does not vary, but y and z vary as shown in Figure 2.9

Figure 2.9 Motion of a particle along two dimensions

Examples

- Motion of a coin on a carrom board.

- An insect crawling over the floor of a room.

(iii) Motion in three dimensions

A particle moving in usual three dimensional space has three dimensional motion.

In this motion, all the three coordinates specifying the position of an object change with respect to time. When a particle moves in three dimensions, all the three coordinates x, y and z will vary.

Examples

- A bird flying in the sky.

- Random motion of a gas molecule.

- Flying of a kite on a windy day.