PHOTO ELECTRIC EFFECT

Hertz, Hallwachs and Lenard’s observation

Hertz observation

Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves and concluded that light itself is just an electromagnetic wave. Then the experimentalists tried to generate and detect electromagnetic waves through various experiments.

In 1887, Heinrich Hertz was successful in generating and detecting electromagnetic wave with his high voltage induction coil causing a spark discharge between two metallic spheres (we have learnt this in Unit 5 of XII standard physics). When a spark is formed, the charges will oscillate back and forth rapidly and the electromagnetic waves are produced.

The electromagnetic waves thus produced were detected by a detector that has a copper wire bent in the shape of a circle. Although the detection of waves is successful, there is a problem in observing the tiny spark produced in the detector.

In order to improve the visibility of the spark, Hertz made many attempts and finally noticed an important thing that small detector spark became more vigorous when it was exposed to ultraviolet light.

The reason for this behaviour of the spark was not known at that time. Later it was found that it is due to the photoelectric emission. Whenever ultraviolet light is incident on the metallic sphere, the electrons on the outer surface are emitted which caused the spark to be more vigorous.

Do You Know ? It is interesting to note that the experiment of Hertz confirmed that light is an electromagnetic wave. But the same experiment also produced the first evidence for particle nature of light.

Hallwachs’ observation

In 1888, Wilhelm Hallwachs, a German physicist, confirmed that the strange behaviour of the spark is due to the action of ultraviolet light with his simple experiment.

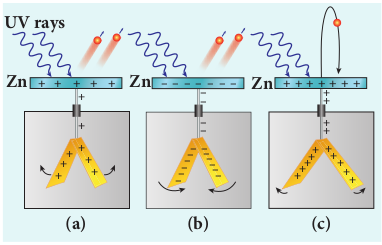

A clean circular plate of zinc is mounted on an insulating stand and is attached to a gold leaf electroscope by a wire. When the uncharged zinc plate is irradiated by ultraviolet light from an arc lamp, it becomes positively charged and the leaves will open as shown in Figure 8.6(a).

Further, if the negatively charged zinc plate is exposed to ultraviolet light, the leaves will come closer as the charges leaked away quickly (Figure 8.6(b)). If the plate is positively charged, it becomes more positive upon UV rays irradiation and the leaves open further (Figure 8.6(c)). From these observations, it was concluded that negatively charged electrons were emitted from the zinc plate under the action of ultraviolet light.

Lenard’s observation

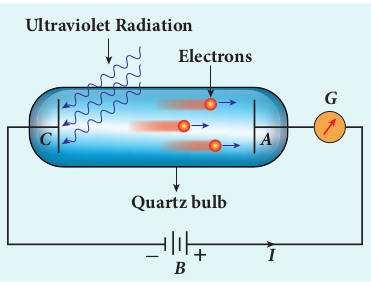

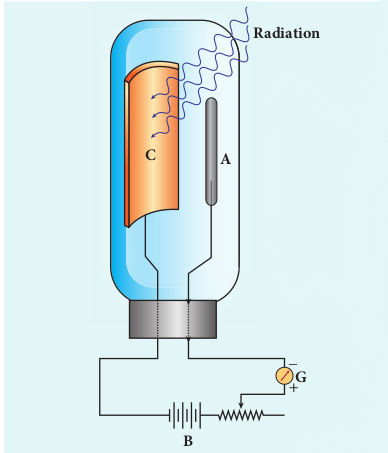

In 1902, Lenard studied this electron emission phenomenon in detail. His simple experimental setup is shown in Figure 8.7. The apparatus consists of two metallic plates A and C placed in an evacuated quartz bulb. The galvanometer G and battery B are connected in the circuit.

When ultraviolet light is incident on the negative plate C, an electric current flows in the circuit that is indicated by the deflection in the galvanometer. On other hand, if the positive plate is irradiated by the ultraviolet light, no current is observed in the circuit.

From these observations, it is concluded that when ultraviolet light falls on the negative plate, electrons are ejected from it which are attracted by the positive plate A. On reaching the positive plate through the evacuated bulb, the circuit is completed and the current flows in it. Thus, the ultraviolet light falling on the negative plate causes the electron emission from the surface of the plate.

Photoelectric effect

The ejection of electrons from a metal plate when illuminated by light or any other electromagnetic radiation of suitable wavelength (or frequency) is called photoelectric effect. Although these electrons are not different from all other electrons, it is customary to call them as photoelectrons and the corresponding current as photoelectric current or photo current.

Metals like cadmium, zinc, magnesium etc show photoelectric emission with ultraviolet light while some alkali metals lithium, sodium, caesium respond well even to larger wavelength radiation like visible light. The materials which eject photoelectrons upon irradiation of electromagnetic wave of suitable wavelength are called photosensitive materials.

Effect of intensity of incident light on photoelectric current

Experimental setup

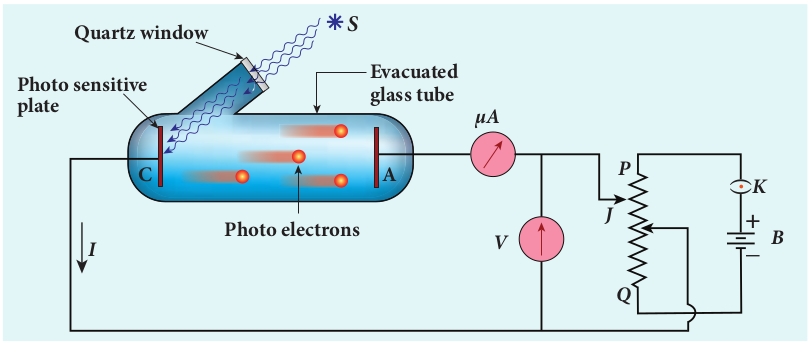

The apparatus shown in Figure 8.8 is employed to study the phenomenon of photoelectric effect in detail. S is a source of electromagnetic waves of known and variable frequency ν and intensity I. C is

the cathode (negative electrode) made up of photosensitive material and is used to emit electrons. The anode (positive electrode) A collects the electrons emitted from C. These electrodes are kept in an evacuated glass envelope with a quartz window that permits the passage of ultraviolet and visible light.

The necessary potential difference between C and A is provided by high tension battery B which is connected across a potential divider arrangement PQ through a key K. C is connected to the centre terminal while A to the sliding contact J of the potential divider. The plate A can be maintained at a desired positive or negative potential with respect to C. To measure both positive and negative potential of A with respect to C, the voltmeter is designed to have its zero marking at the centre and is connected between A and C. The current is measured by a micro ammeter mA connected in series.

If there is no light falling on the cathode C, no photoelectrons are emitted and the microammeter reads zero. When ultraviolet or visible light is allowed to fall on C, the photoelectrons are liberated and are attracted towards anode. As a result, the photoelectric current is set up in the circuit which is measured using micro ammeter.

The variation of photocurrent with respect to (i) intensity of incident light (ii) the potential difference between the electrodes (iii) the nature of the material and (iv) frequency of incident light can be studied with the help of this arrangement.

Effect of intensity of incident light on photoelectric current

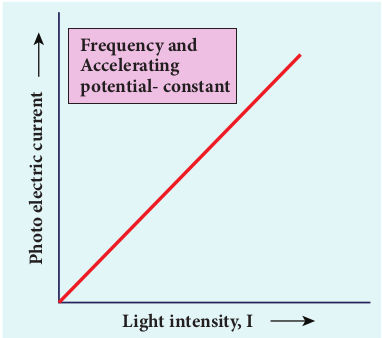

To study the effect of intensity of incident light on photoelectric current, the frequency of the incident light and the accelerating potential V of the anode are kept constant. Here the potential of A is kept positive with respect to that of C so that the electrons emitted from C are attracted towards A. Now, the intensity of the incident light is varied and the corresponding photoelectric current is measured.

A graph is drawn between light intensity along x-axis and the photocurrent along y-axis. From the graph in Figure 8.9, it is evident that photocurrent – the number of electrons emitted per second – is directly proportional to the intensity of the incident light.

Note

Here, intensity of light means brightness. A bright light has more intensity than a dim light.

Effect of potential difference on photoelectric current

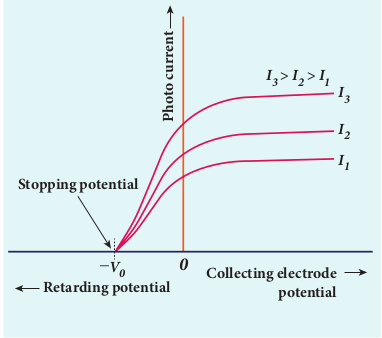

To study the effect of potential difference V between the electrodes on photoelectric current, the frequency and intensity of the incident light are kept constant. Initially the potential of A is kept positive with respect to C and the cathode is irradiated with the given light.

Now, the potential of A is increased and the corresponding photocurrent is noted. As the potential of A is increased, photocurrent also increases. However a stage is reached where photocurrent reaches a saturation value (saturation current) at which all the photoelectrons from C are collected by A. This is represented by the flat portion of the graph between potential of A and photocurrent (Figure 8.10).

When a negative (retarding) potential is applied to A with respect to C, the current does not immediately drop to zero because the photoelectrons are emitted with some definite and different kinetic energies. The kinetic energy of some of the photoelectrons is such that they could overcome the retarding electric field and reach the electrode A.

When the negative (retarding) potential of A is gradually increased, the photocurrent starts to decrease because more and more photoelectrons are being repelled away from reaching the electrode A. The photocurrent becomes zero at a particular negative potential Vo, called stopping or cut-off potential.

Stopping potential is that value of the negative (retarding) potential given to the collecting electrode A which is just sufficient to stop the most energetic photoelectrons emitted and make the photocurrent zero.

At the stopping potential, even the most energetic electron is brought to rest. Therefore, the initial kinetic energy of the fastest electron \(\left(K_{\max }\right)\) is equal to the work done by the stopping potential to stop it \(\left(e V_{0}\right)\).

\(K_{\max }=\frac{1}{2} m v_{\max }^{2}=e V_{0}\)

where \(v_{\max }\) is the maximum speed of the emitted photoelectron.

\(\begin{aligned} v_{\max } & =\sqrt{\frac{2 e V_{0}}{m}} \\ v_{\max } & =\sqrt{\frac{2 \times 1.602 \times 10^{-19}}{9.1 \times 10^{-31}} \times V_{0}} \\ & =5.93 \times 10^{5} \sqrt{V_{0}} \end{aligned}\)From equation (8.1),

\(\begin{aligned} & K_{\max }=e V_{0}(\text { in joule }) \\ & K_{\max }=V_{0}(\text { in } \mathrm{eV}) \end{aligned}\)From the Figure 8.10, when the intensity of the incident light alone is increased, the saturation current also increases but the value of \(V_{0}\) remains constant.

Thus, for a given frequency of the incident light, the stopping potential is independent of intensity of the incident light. This also implies that the maximum kinetic energy of the photoelectrons is independent of intensity of the incident light.

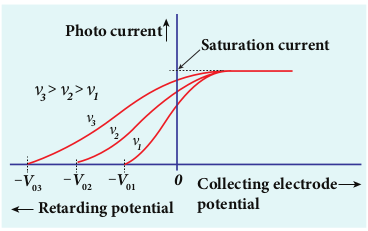

Effect of frequency of incident light on stopping potential

To study the effect of frequency of incident light on stopping potential, the intensity of the incident light is kept constant. The variation of photocurrent with the collecting electrode potential is studied for radiations of different frequencies and a graph drawn between them is shown in Figure 8.11. From the graph, it is clear that stopping potential vary over different frequencies of incident light.

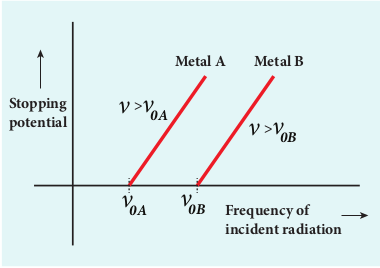

Now a graph is drawn between frequency of incident radiation and the stopping potential for different metals (Figure 8.12). From this graph, it is found that stopping potential varies linearly with frequency. Below a certain frequency called threshold frequency, no electrons are emitted; hence stopping potential is zero for that reason. But as the frequency is increased above threshold value, the stopping potential varies linearly with the frequency of incident light.

Laws of photoelectric effect

The above detailed experimental investigations of photoelectric effect revealed the following results: i) For a given metallic surface, the emission of photoelectrons takes place only if the frequency of incident light is greater than a certain minimum frequency called the threshold frequency. ii) For a given frequency of incident light (above threshold value), the number of photoelectrons emitted is directly proportional to the intensity of the incident light. The saturation current is also directly proportional to the intensity of incident light. iii) Maximum kinetic energy of the photo electrons is independent of intensity of the incident light. iv) Maximum kinetic energy of the photo electrons from a given metal is directly proportional to the frequency of incident light. v) There is no time lag between incidence of light and ejection of photoelectrons.

Once photoelectric phenomenon has been thoroughly examined through various experiments, the attempts were made to explain it on the basis of wave theory of light.

Concept of quantization of energy

Failures of classical wave theory

From Maxwell’s theory (Refer unit 5 of volume 1), we learnt that light is an electromagnetic wave consisting of coupled electric and magnetic oscillations that move with the speed of light and exhibit typical wave behaviour. Let us try to explain the experimental observations of photoelectric effect using wave picture of light.

(i) When light is incident on a metallic surface, there is a continuous supply of energy to the electrons in the metal surface. According to wave theory, light of greater intensity should impart greater kinetic energy to the liberated electrons (Here, Intensity of light is the energy delivered per unit area per unit time).But this does not happen. The experiments show that maximum kinetic energy of the photoelectrons emitted does not depend on the intensity of the incident light.

(ii) According to wave theory, if a sufficiently intense beam of light is incident on the surface, electrons should be liberated from the surface of the target, however low the frequency of the radiation is. From the experiments, it is found that photoelectric emission is not possible below a certain minimum frequency of incident radition. Therefore, the wave theory fails to explain the existence of threshold frequency.

(iii) Since the energy of light is spread across the entire wavefront, the electrons which receive energy from it are large in number. Each electron needs considerable amount of time (a few hours) to get energy sufficient to overcome the work function and to get liberated from the surface.

But experiments show that photoelectric emission is almost instantaneous process (the time lag is less than \(10^{-9} \mathrm{~s}\) after the surface is illuminated) which could not be explained by wave theory.

Thus, the experimental observations of photoelectric emission could not be explained on the basis of the wave theory of light.

EXAMPLE 8.1

For the photoelectric emission from cesium, show that wave theory predicts that

i) maximum kinetic energy of the photoelectrons \(\left(K_{\max }\right)\) depends on the intensity \(I\) of the incident light

ii) \(K_{\max }\) does not depend on the frequency of the incident light and

iii) the time interval between the incidence of light and the ejection of photoelectrons is very long. For the sake of simplicity, the following standard assumptions can be made when light is incident on the given material.

a) Light is absorbed in the top atomic layer of the metal

b) For a given element, each atom absorbs an equal amount of energy and this energy is proportional to its cross-sectional area \(A\)

c) Each atom gives this energy to one of the electrons.

(Given : The work function for cesium is \(2.14 \mathrm{eV}\) and the power absorbed per unit area is \(1.60 \times 10^{-6} \mathrm{Wm}^{-2}\) which produces a measurable photocurrent in cesium.)

Solution

i) According to wave theory, the energy in a light wave is spread out uniformly and continuously over the wavefront.

The energy absorbed by each electron in time \(t\) is given by

\(E=I A t\)With this energy absorbed, the most energetic electron is released with \(K_{\text {max }}\) by overcoming the surface energy barrier or work function \(\phi_{0}\) and this is expressed as

\(K_{\max }=I A t-\phi_{0}\)Thus, wave theory predicts that for a unit time, at low light intensities when \(I A<\phi_{0}\) , no electrons are emitted. At higher intensities, when \(I A \geq \phi_{0}\) , electrons are emitted. This implies that higher the light intensity, greater will be \(K_{\max }\)

\(K_{\text {max }}\) is dependent only on the intensity under given conditions - that is, by suitably increasing the intensity, one can produce photoelectric effect even if the frequency is less than the threshold frequency. So the concept of threshold frequency does not even exist in wave theory.

ii) According to wave theory, the intensity of a light wave is proportional to the square of the amplitude of the electric field \(\left(E_{0}^{2}\right)\) . The amplitude of this electric field increases with increasing intensity and imparts an increasing acceleration and kinetic energy to an electron.

Now \(I\) is replaced with a quantity proportional to \(E_{0}^{2}\) in equation (1). This means that \(K_{\max }\) should not depend at all on the frequency of the classical light wave which again contradicts the experimental results.

iii) If an electron accumulates light energy just enough to overcome the work function, then it is ejected out of the atom with zero kinetic energy. Therefore, from equation (1),

\(\begin{aligned} & 0=I A t-\phi_{0} \\ & t=\frac{\phi_{0}}{I A}=\frac{\phi_{0}}{I\left(\pi r^{2}\right)} \end{aligned}\)By taking the atomic radius \(r=1.0 \times 10^{-10} \mathrm{~m}\) and substituting the given values of \(I\) and \(\phi_{0}\) , we can estimate the time interval as

\(\begin{aligned} t & =\frac{2.14 \times 1.6 \times 10^{-19}}{1.60 \times 10^{-6} \times 3.14 \times\left(1 \times 10^{-10}\right)^{2}} \\ & =0.68 \times 10^{7} s \approx 79 \text { days } \end{aligned}\)Thus, wave theory predicts that there is a large time gap between the incidence of light and the ejection of photoelectrons but the experiments show that photo emission is an instantaneous process.

Concept of quantization of energy

Max Planck proposed quantum concept in 1900 in order to explain the thermal radiations emitted by a black body and the shape of its radiation curves.

According to Planck, matter is composed of a large number of oscillating particles (atoms) which vibrate with different frequencies. Each atomic oscillator - which vibrates with its characteristic frequency emits or absorbs electromagnetic radiation of the same frequency. It also says that

i) If an oscillator vibrates with frequency \(v\) , its energy can have only certain discrete values, given by the equation.

\(E_{\mathrm{n}}=n h v \quad n=1,2,3 \ldots\)where \(h\) is a constant, called Planck’s constant.

ii) The oscillators emit or absorb energy in small packets or quanta and the energy of each quantum is \(h v\) .

This implies that the energy of the oscillator is quantized - that is, energy is not continuous as believed in the wave picture. This is called quantization of energy.

Particle nature of light: Einstein’s explanation

Einstein extended Planck’s quantum concept to explain the photoelectric effect in 1905. According to Einstein, the energy in light is not spread out over wavefronts but is concentrated in small packets or energy quanta. Therefore, light (or any other electromagnetic waves) of frequency \(v\) from any source can be considered as a stream of quanta and the energy of each light quantum is given by \(E=h v\) .

He also proposed that a quantum of light has linear momentum and the magnitude of that linear momentum is \(p=\frac{h v}{c}\) . The individual light quantum of definite energy and momentum can be associated with a particle. The light quantum can behave as a particle and this is called photon. Therefore, photon is nothing but particle manifestation of light.

Characteristics of photons:

According to particle nature of light, photons are the basic constituents of any radiation and possess the following characteristic properties:

i) The photons of light of frequency \(v\) and wavelength \(\lambda\) will have energy, given by

\(E=h v=\frac{h c}{\lambda}\)ii) The energy of a photon is determined by the frequency of the radiation and not by its intensity and the intensity has no relation with the energy of the individual photons in the beam.

iii) The photons travel with the speed of light and its momentum is given by

\(p=\frac{h}{\lambda}=\frac{h v}{c}\)iv) Since photons are electrically neutral, they are unaffected by electric and magnetic fields.

v) When a photon interacts with matter (photon-electron collision), the total energy, total linear momentum and angular momentum are conserved. Since photon may be absorbed or a new photon may be produced in such interactions, the number of photons may not be conserved.

Note According to quantum concept, intensity of light of given wavelength is defined as the number of energy quanta or photons incident per unit area per unit time, with each photon having same energy. Its unit is Wm–2.

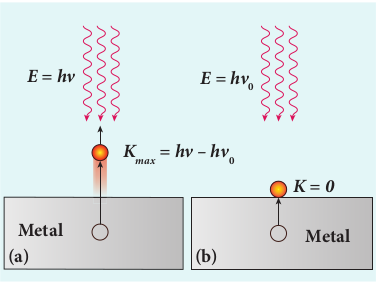

Einstein’s explanation of photoelectric equation

When a photon of energy \(h v\) is incident on a metal surface, it is completely absorbed by a single electron and the electron is ejected. In this process, a part of the photon energy is used in overcoming the potential barrier of the metal surface (photoelectric work function \(\phi_{0}\) ) and the remaining energy as the kinetic energy of the ejected electron. From the law of conservation of energy,

\(h v=\phi_{0}+\frac{1}{2} m v^{2}\)where \(m\) is the mass of the electron and \(v\) its velocity. This is shown in Figure 8.13(a).

Figure 8.13 Emission of photoelectrons

If we reduce the frequency of the incident light, the speed or kinetic energy of photo electrons is also reduced. At some frequency \(v_{0}\) of incident radiation, the photo electrons are just ejected with almost zero kinetic energy (Figure 8.13(b)). Then the equation (8.6) becomes

\(h v_{0}=\phi_{0}\)where \(v_{0}\) is the threshold frequency. By rewriting the equation (8.6), we get

\(h v=h v_{0}+\frac{1}{2} m v^{2}\)The equation (8.7) is known as Einstein’s photoelectric equation.

If the electron does not lose energy by internal collisions, then it is emitted with maximum kinetic energy \(K_{\max }\) . Then

\(K_{\max }=\frac{1}{2} m v_{\max }^{2}\)where \(v_{\max }\) is the maximum velocity of the electron ejected. The equation (8.6) is rearranged as follows:

\(K_{\max }=h v-\phi_{0}\)

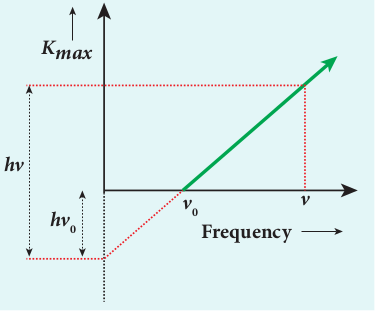

Figure 8.14 \(K_{\max }\) vs \(v\) graph

A graph between maximum kinetic energy \(K_{\max }\) of the photoelectron and frequency \(v\) of the incident light is a straight line as shown in Figure 8.14. The slope of the line is \(h\) and its y-intercept is \(-\phi_{0}\) .

Einstein’s equation was experimentally verified by R.A. Millikan. He drew \(K_{\max }\) versus \(v\) graph for many metals (cesium, potassium, sodium and lithium) as shown in Figure 8.15 and found that the slope is independent of the metals.

Figure 8.15 \(K_{\max }\) vs \(v\) graph for different metals

Millikan also calculated the value of Planck’s constant \(\left(h=6.626 \times 10^{-34} \mathrm{Js}\right)\) and work function of many metals (Cs, K, Na, \(\mathrm{Ca}\) ); these values are in agreement with the theoretical prediction.

Explanation for the photoelectric effect:

The experimentally observed facts of photoelectric effect can be explained with the help of Einstein’s photoelectric equation.

i) As each incident photon liberates one electron, then the increase of intensity of the light (the number of photons per unit area per unit time) increases the number of electrons emitted thereby increasing the photocurrent. The same has been experimentally observed.

ii) From \(K_{\max }=h v-\phi_{0}\) , it is evident that \(K_{\max }\) is proportional to the frequency of the incident light and is independent of intensity of the light.

iii) As given in equation (8.7), there must be minimum energy (equal to the work function of the metal) for incident photons to liberate electrons from the metal surface. Below this value of energy, emission of electrons is not possible. Correspondingly, there exists minimum frequency called threshold frequency below which there is no photoelectric emission. iv) According to quantum concept, the transfer of photon energy to the electrons is instantaneous so that there is no time lag between incidence of photons and ejection of electrons.

Thus, the photoelectric effect is explained on the basis of quantum concept of light.

The nature of light: wave - particle duality

We have learnt that wave nature of light explains phenomena such as interference, diffraction and polarization. Certain phenomena like black body radiation, photoelectric effect can be explained by assigning particle nature to light. Therefore, both theories have enough experimental evidences.

In the past, many scientific theories have been either revised or discarded when they contradicted with new experimental results. Here, two different theories are needed to answer the question: what is nature of light?

It is therefore concluded that light possesses dual nature, that of both particle and wave. It behaves like a wave at some circumstances and it behaves like a particle at some other circumstances.

In other words, light behaves as a wave during its propagation and behaves as a particle during its interaction with matter. Both theories are necessary for complete description of physical phenomena. Hence, the wave nature and quantum nature complement each other.

A reader may find it difficult to u stream of particle. This is the case ev Einstein once wrote a letter to his frustration:

“All these fifty years of conscious broodin question, ‘What are light quanta?’ Of course t but he is deluding himself ”.

Photo electric cells and their applications

Photo cell

Photo electric cell or photo cell is a device which converts light energy into electrical energy. It works on the principle of photo electric effect. When light is incident on the photosensitive materials, their electric properties will get affected, based on which photo cells are classified into three types. They are

i) Photo emissive cell: Its working depends on the electron emission from a metal cathode due to irradiation of light or other radiations.

ii) Photo voltaic cell: Here sensitive element made of semiconductor is used which generates voltage proportional to the intensity of light or other radiations.

iii) Photo conductive cell: In this, the resistance of the semiconductor changes in accordance with the radiant energy incident on it. In this section, we discuss about photo emissive cell and its applications.

Do you know:

A reader may find it difficult to understand how light can be both a wave and a stream of particle. This is the case even for great scientist like Albert Einstein. Einstein once wrote a letter to his friend Michel Besso in 1954 expressing his frustration: “All these fifty years of conscious brooding have brought me no closer to answer the question, ‘What are light quanta?’ Of course today everyone thinks he knows the answer, but he is deluding himself ”

Photo emissive cell

Construction:

It consists of an evacuated glass or quartz bulb in which two metallic electrodes – that is, a cathode and an anode are fixed as shown in Figure 8.16.

Figure 8.16 Construction of photo cell

Working:

When cathode is irradiated with suitable radiation, electrons are emitted from it. These electrons are attracted by anode and hence a current is produced which is measured by the galvanometer. For a given cathode, the magnitude of the current depends on i) the intensity of incident radiation and ii) the potential difference between anode and cathode.

Applications of photo cells:

Photo cells have many applications, especially as switches and sensors. Automatic lights that turn on when it gets dark use photocells, and street lights that switch on and switch off according to whether it is night or day use photocells.

Photo cells are used for reproduction of sound in motion pictures and are used as timers to measure the speeds of athletes during a race. Photo cells of exposure meters in photography are used to measure the intensity of the given light and to calculate the exact time of exposure.

EXAMPLE 8.2 A radiation of wavelength \(300 \mathrm{~nm}\) is incident on a silver surface. Will photoelectrons be observed? [work function of silver \(=4.7 \mathrm{eV}\) ]

Solution: Energy of the incident photon is

\(\begin{aligned} & E=h v=\frac{h c}{\lambda} \text { (in joules) } \\ & E=\frac{h c}{\lambda e}(\text { in } \mathrm{eV}) \end{aligned}\)Substituting the known values, we get

\(E=\frac{6.626 \times 10^{-34} \times 3 \times 10^{8}}{300 \times 10^{-9} \times 1.6 \times 10^{-19}}\) \(E=4.14 \mathrm{eV}\)The work function of silver \(=4.7 \mathrm{eV}\) . Since the energy of the incident photon is less than the work function of silver, photoelectrons are not observed in this case.

EXAMPLE 8.3 When light of wavelength \(2200 A\) falls on \(\mathrm{Cu}\) , photo electrons are emitted from it. Find (i) the threshold wavelength and (ii) the stopping potential. Given: the work function for \(\mathrm{Cu}\) is \(\phi_{0}=4.65 \mathrm{eV}\) .

Solution i) The threshold wavelength is given by

\(\begin{aligned} \lambda_{0} & =\frac{h c}{\phi_{0}}=\frac{6.626 \times 10^{-34} \times 3 \times 10^{8}}{4.65 \times 1.6 \times 10^{-19}} \\ & =2672 A \end{aligned}\)ii) Energy of the photon of wavelength \(2200 A\) is

\(\begin{aligned} E & =\frac{h c}{\lambda}=\frac{6.626 \times 10^{-34} \times 3 \times 10^{8}}{2200 \times 10^{-10}} \\ & =9.035 \times 10^{-19} \mathrm{~J}=5.65 \mathrm{eV} \end{aligned}\)We know that kinetic energy of fastest photo electron is

\(\begin{aligned} K_{\max } & =h v-\phi_{0}=5.65-4.65 \\ & =1 \mathrm{eV} \end{aligned}\)From equation (8.3), \(K_{\max }=e V_{0}\)

\(V_{0}=\frac{K_{\max }}{e}=\frac{1 \times 1.6 \times 10^{-19}}{1.6 \times 10^{-19}}\)Therefore, stopping potential \(=1 \mathrm{~V}\)

EXAMPLE 8.4 The work function of potassium is \(2.30 \mathrm{eV}\) . UV light of wavelength \(3000 \AA\) and intensity \(2 \mathrm{Wm}^{-2}\) is incident on the potassium surface. i) Determine the maximum kinetic energy of the photo electrons ii) If \(40 \%\) of incident photons produce photo electrons, how many electrons are emitted per second if the area of the potassium surface is \(2 \mathrm{~cm}^{2}\) ?

Solution i) The work function is given by

\(\begin{aligned} & \phi_{0}=h v-K_{\max }=\frac{h c}{\lambda}-e V_{0} \\ & =\left[\frac{6.626 \times 10^{-34} \times 3 \times 10^{8}}{390 \times 10^{-9}}\right]-\left[1.6 \times 10^{-19} \times 1.10\right] \\ & =5.10 \times 10^{-19}-1.76 \times 10^{-19}=3.34 \times 10^{-19} \mathrm{~J} \\ & =2.09 \mathrm{eV} \end{aligned}\)ii) The threshold wavelength is

\(\begin{aligned} \lambda_{0} & =\frac{h c}{\phi_{0}}=\frac{6.626 \times 10^{-34} \times 3 \times 10^{8}}{3.34 \times 10^{-19}} \\ & =5.951 \times 10^{-7} \mathrm{~m}=5951 A \end{aligned}\)EXAMPLE 8.5 Light of wavelength \(390 \mathrm{~nm}\) is directed at a metal electrode. To find the energy of electrons ejected, an opposing potential difference is established between it and another electrode. The current of photoelectrons from one to the other is stopped completely when the potential difference is \(1.10 \mathrm{~V}\) . Determine i) the work function of the metal and ii) the maximum wavelength of light that can eject electrons from this metal.

Solution i) The work function is given by

\(\begin{aligned} & \phi_{0}=h v-K_{\max }=\frac{h c}{\lambda}-e V_{0} \\ & =\left[\frac{6.626 \times 10^{-34} \times 3 \times 10^{8}}{390 \times 10^{-9}}\right]-\left[1.6 \times 10^{-19} \times 1.10\right] \\ & =5.10 \times 10^{-19}-1.76 \times 10^{-19}=3.34 \times 10^{-19} \mathrm{~J} \\ & =2.09 \mathrm{eV} \end{aligned}\)ii) The threshold wavelength is

\(\begin{aligned} \lambda_{0} & =\frac{h c}{\phi_{0}}=\frac{6.626 \times 10^{-34} \times 3 \times 10^{8}}{3.34 \times 10^{-19}} \\ & =5.951 \times 10^{-7} \mathrm{~m}=5951 A \end{aligned}\)