UNIT 8: DUAL NATURE OF RADIATION AND MATTER

Learning Objectives In this unit, the students are exposed to

- the phenomenon of electron emission and its types

- the observations of Hertz, Hallwachs and Lenard

- photoelectric effect and its laws

- the concept of quantization of energy

- photo cell and its applications

- particle nature of radiation

- the wave nature of matter

- de Broglie equation and de Broglie waveleng

- the construction and working of electron microscope

- Davisson and Germer experiment

- X-rays and its production

- X-rays spectra and its types

INTRODUCTION

We are familiar with the concepts of particle and wave in our everyday experience. Marble balls, grains of sand, atoms, electrons and so on are some examples of particles while the examples of waves are sea waves, ripples in a pond, sound waves and light waves.

Particle is a material object which is considered as a tiny concentration of matter (localized in space and time) whereas wave is a broad distribution of energy (not localized in space and time). They, both particles and waves, have the ability to carry energy and momentum from one place to another.

Classical physics which describes the motion of the macroscopic objects treats particles and waves as separate components of physical reality. The mechanics of particles and the optics of waves are traditionally independent subjects, each with its own experiments and principles.

Electromagnetic radiations are regarded as waves because they exhibit wave nature in phenomena such as interference, diffraction and polarization under some suitable circumstances. Similarly, under other circumstances like black body radiation and photo electric effect, electromagnetic radiations behave as though they consist of stream of particles.

When electrons, protons and other particles are discovered, they are considered as particles because they possess mass and charge. However, later experiments showed that under certain circumstances, they exhibit wave-like properties also.

In this unit, the particle nature of waves (radiation) and the wave nature of particles (matter) – that is, wave-particle duality of radiation and matter is discussed with the relevant experimental observations supporting this dual nature.

Electron emission

In metals, the electrons in the outer most shells are loosely bound to the nucleus. Even at room temperature, there are a large number of free electrons which are moving inside the metal in a random manner. Though they move freely inside the metal, they cannot leave the surface of the metal. The reason is that when free electrons reach the surface of the metal, they are attracted by the positive nuclei of the metal. It is this attractive pull which will not allow free electrons to leave the metallic surface at room temperature.

In order to leave the metallic surface, the free electrons must cross a potential barrier created by the positive nuclei of the metal. The potential barrier which prevents free electrons from leaving the metallic surface is called surface barrier.

Free electrons possess some kinetic energy and this energy is different for different electrons. The kinetic energy of the free electrons is not sufficient to overcome the surface barrier. Whenever an additional energy is given to the free electrons, they will have sufficient energy to cross the surface barrier and they escape from the metallic surface**. The liberation of electrons from any surface of a substance is called electron emission.

The minimum energy needed for an electron to escape from the metal surface is called work function of that metal. The work function of the metal is denoted by φ0 and is measured in electron volt (eV).

Note The SI unit of energy is joule. But electron volt is a commonly used unit of energy in atomic and nuclear physics. One electron volt is defined as the kinetic energy gained by an electron when accelerated by a potential difference of 1 V.

Suppose the maximum kinetic energy of the free electron inside the metal is 0.5 eV and the energy needed to overcome the surface barrier of a metal is 3 eV, then the minimum energy needed for electron emission from the metallic surface is 3 – 0.5 = 2.5 eV. Here 2.5 eV is the work function of the metal.

The work function is different for different metals and is a typical property of metals and the nature of their surface. Table 8.1 gives the approximate value of work function for various metals. The material with smaller work function is more effective in electron emission because extra energy required to release the free electrons from the metal surface is smaller. Table 8.1 Work function of some materials

| Metal | Symbol | Work function (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| Cesium | Cs | 2.14 |

| Potassium | K | 2.30 |

| Sodium | Na | 2.75 |

| Calcium | Ca | 3.20 |

| Molybdenum | Mo | 4.17 |

| Lead | Pb | 4.25 |

| Aluminium | Al | 4.28 |

| Mercury | Hg | 4.49 |

| Copper | Cu | 4.65 |

| Silver | Ag | 4.70 |

| Nickel | Ni | 5.15 |

| Platinum | Pt | 5.65 |

So the metal selected for electron emission should have low work function. The electron emission is categorized into different types depending upon the form of energy being utilized. There are mainly four types of electron emission which are given below.

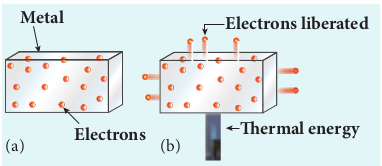

(i) Thermionic emission

When a metal is heated to a high temperature, the free electrons on the surface of the metal get sufficient energy in the form of thermal energy so that they are emitted from the metallic surface (Figure 8.1). This type of emission is known as thermionic emission.

The intensity of the thermionic emission (the number of electrons emitted) depends on the metal used and its temperature. Examples: cathode ray tubes, electron microscopes, x-ray tubes etc (Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2 Thermionic emission from hot filament of cathode ray tube or x-ray tube

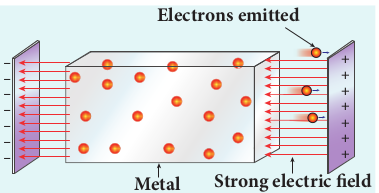

(ii) Field emission Electric field emission occurs when a

very strong electric field is applied across the metal. This strong field pulls the free electrons and helps them to overcome the surface barrier of the metal (Figure 8.3). Examples: Field emission scanning electron microscopes, Field-emission display etc.

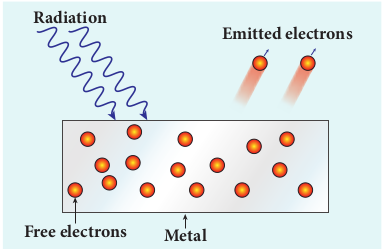

(iii) Photo electric emission

When an electromagnetic radiation of suitable frequency is incident on the surface of the metal, the energy is transferred from the radiation to the free electrons. Hence, the free electrons get sufficient energy to cross the surface barrier and the photo electric emission takes place (Figure 8.4). The number of electrons emitted depends on the intensity of the incident radiation. Examples: Photo diodes, photo electric cells etc.

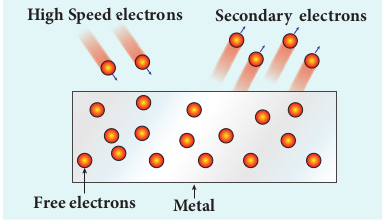

(iv) Secondary emission

When a beam of fast moving electrons strikes the surface of the metal, the kinetic energy of the striking electrons is transferred to the free electrons on the metal surface. Thus the free electrons get sufficient kinetic energy so that the secondary emission of electron occurs (Figure 8.5). Examples: Image intensifiers, photo multiplier tubes etc.