Body Fluids

The body fluid consists of water and substances dissolved in them. There are two types of body fluids, the intracellular fluid present inside the cells and the extracellular fluid present outside the cells. The three types of extracellular fluids are the interstitial fluid or tissue fluid (surrounds the cell), the plasma (fluid component of the blood) and lymph. The blood flowing into the capillary from an arteriole has a high hydrostatic pressure. This pressure is brought about by the pumping action of the blood and it tends to force water and small molecules out through the permeable walls of the capillary into the tissue fluid.

The volume of fluid which leaves the capillary to form tissue fluid is the result of two pressure (hydrostatic pressure and Oncotic pressure). At the anterior end of the capillary bed, the water potential is lesser than hydrostatic pressure inside the capilary bed which is enough to push fluid into the tissues. The tissue fluid has low concentration of protien than that of plasma. At the venous end of the capillary bed, the water potential is greater than the hydrostatic pressure and the fluid from the tissues flows into the capillary and water is drawn back into the blood, taking with it waste products produced by the cells.

Composition of Blood

Blood is the most common body fluid that transports substances from one part of the body to the other. Blood is a connective tissue consisting of plasma (fluid matrix) and formed elements. The plasma constitutes 55% of the total blood volume. The remaining 45% is the formed elements that consist of blood cells. The average blood volume is about 5000ml (5L) in an adult weighing 70 Kg.

Plasma

Plasma mainly consists of water (80-92%) in which the plasma proteins, inorganic constituents (0.9%), organic constituents (0.1%) and respiratory gases are dissolved. The four main types of plasma proteins synthesized in the liver are albumin, globulin, prothrombin and fibrinogen. Albumin maintains the osmotic pressure of the blood. Globulin facilitates the transport of ions, hormones, lipids and assists in immune function. Both Prothrombin and Fibrinogen are involved in blood clotting. Organic constituents include urea, amino acids, glucose, fats and vitamins and the inorganic constituents include chlorides, carbonates and phosphates of potassium, sodium, calcium and magnesium. The composition of plasma is not always constant. Immediately after a meal, the blood in the hepatic portal vein has a very high concentration of glucose as it is transporting glucose from the intestine to the liver where it is stored. The concentration of the glucose in the blood gradually falls after sometime as most of the glucose is absorbed. If too much of protein is consumed, the body cannot store the excess amino acids formed from the digestion of proteins. The liver breaks down the excess amino acids and produces urea. Blood in the hepatic vein has a high concentration of urea than the blood in other vessels namely, hepatic portal vein and hepatic artery.

**Liver receives its blood supply from two sources:** the hepatic artery brings oxygenated blood from the heart, while the hepatic portal vein brings blood from the intestine and other abdominal organs. The blood is re- turned from the liver to the heart by the hepatic veins.

Formed Elements

Red blood cells/corpuscles (erythrocytes), white blood cells/corpuscles (Leucocytes) and platelets are collectively called formed elements.

Red Blood Cells

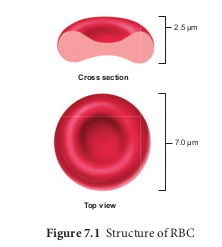

Red blood cells are abundant than the other blood cells. There are about 5 million to 5.5 millions of RBC mm23 of blood in a healthy man and 4.5-5.0 millions of RBC mm23 in healthy women. The RBCs are very small with the diameter of about 7µm (micrometer). The structure of RBC is shown in Figure 7.1. The red colour of the RBC is due to the presence of a respiratory pigment, haemoglobin dissolved in the cytoplasm. Haemoglobin plays an important role in the transport of respiratory gases and facilitates the exchange of gases with the fluid outside the cell (tissue fluid). The biconcave shaped RBCs increases the surface area to volume ratio, hence oxygen diffuses quickly in and out of the cell. The RBCs are devoid of nucleus, mitochondria, ribosomes and endoplasmic reticulum. The absence of these organelles accommodates more haemoglobin thereby maximising the oxygen carrying capacity of the cell. The average life span of RBCs in a healthy individual is about 120 days after which they are destroyed in the spleen (graveyard / cemetery of RBCs) and the iron component returns to the bone marrow for reuse. Erythropoietin is a hormone secreted by the kidneys in response to low oxygen and helps in differentiation of stem cells of the bone marrow to erythrocytes (erythropoiesis) in adults. The ratio of red blood cells to blood plasma is expressed as Haematocrit (packed cell volume).

White Blood Cells

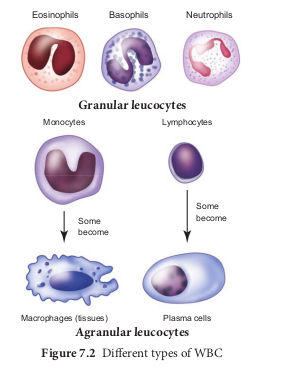

White blood cells (leucocytes) are colourless, amoeboid, nucleated cells devoid of haemoglobin and other pigments. Approximately 6000 to 8000 per cubic mm of WBCs are seen in the blood of an average healthy individual. The different types of WBCs are shown in Figure 7.2. Depending on the presence or absence of granules, WBCs are divided into two types, granulocytes and agranulocytes.

Granulocytes

Granulocytes are characterised by the presence of granules in the cytoplasm and are differentiated in the bone marrow. The granulocytes include neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils.

Neutrophils are also called heterophils or polymorphonuclear (cells with 3-4 lobes of nucleus connected with delicate threads) cells which constitute about 60%- 65% of the total WBCs. They are phagocytic in nature and appear in large numbers in and around the infected tissues.

Eosinophils have distinctly bilobed nucleus and the lobes are joined by thin strands. They are non-phagocytic and constitute about 2-3% of the total WBCs. Eosinophils increase during certain types of parasitic infections and allergic reactions.

Basophils are less numerous than any other type of WBCs constituting 0.5%- 1.0% of the total number of leucocytes. The cytoplasmic granules are large sized, but fewer than eosinophils. Nucleus is large sized and constricted into several lobes but not joined by

delicate threads. Basophils secrete substances such as heparin, serotonin and histamines. They are also involved in inflammatory reactions.

Agranulocytes

Agranulocytes are characterised by the absence of granules in the cytoplasm and are differentiated in the lymph glands and spleen. These are of two types, lymphocytes and monocytes.

Lymphocytes constitute 28% of WBCs. These have large round nucleus and small amount of cytoplasm. The two types of lymphocytes are B and T cells. Both B and T cells are responsible for the immune responses of the body. B cells produce antibodies to neutralize the harmful effects of foreign substances and T cells are involved in cell mediated immunity.

Monocytes (Macrophages) are phagocytic cells that are similar to mast

cells and have kidney shaped nucleus. They constitute 1-3% of the total WBCs. The macrophages of the central nervous system are the ‘microglia’, in the sinusoids of the liver they are called ‘Kupffer cells’ and in the pulmonary region they are the ‘alveolar macrophages’.

Platelets

Platelets are also called thrombocytes that are produced from megakaryocytes (special cells in bone marrow) and lack nuclei. Blood normally contains 1, 50,000 -3, 50,000 platelets mm23 of blood. They secrete substances involved in coagulation or clotting of blood. The reduction in platelet number can lead to clotting disorders that result in excessive loss of blood from the body.

Blood Groups

Commonly two types of blood groupings are done. They are ABO and Rh which are widely used all over the world.

ABO Blood Grouping

Depending on the presence or absence of surface antigens on the RBCs, blood group in individual belongs to four different types namely, A, B, AB and O. The plasma of A, B and O individuals have natural antibodies (agglutinins) in them. Surface antigens are called agglutinogens. The antibodies (agglutinin) acting on agglutinogen A is called anti A and the agglutinin acting on agglutinogen B is called anti B. Agglutinogens are absent in O blood group. Agglutinogens A and B are present in AB blood group and do not contain anti A and anti B in them. Distribution of antigens and antibodies in blood groups are shown in Table 7.1. A, B and O are major allelic genes in ABO systems. All agglutinogens contain sucrose, D-galactose, N-acetyl glucosamine and 11 terminal amino acids. The attachments of the terminal amino acids are dependent on the gene products of A and B. The reaction is catalysed by glycosyl transferase.

Distribution of antigens and antibodies in different blood groups

| Bloodgroup | Agglutinogens(antigens) on the RBC | Agglutinin(antibodies)in the plasma |

|---|---|---|

| A | A | Anti B |

| B | B | Anti A |

| AB | AB | No antibodies |

| O | No antigens | Anti A and Anti B |

Rh factor is a protein (D antigen) present on the surface of the red blood cells in majority (80%) of humans. This protein is similar to the protein present in Rhesus monkey, hence the term Rh. Individuals who carry the antigen D on the surface of the red blood cells are Rh1 (Rh positive) and the individuals who do not carry antigen D, are Rh2 (Rh negative). Rh factor compatibility is also checked before blood transfusion. When a pregnant women is Rh2 and the foetus is Rh1 incompatibility (mismatch) is observed. During the first pregnancy, the Rh2 antigens of the foetus does not get exposed to the mother’s blood as both their blood are separated by placenta. However, small amount of the foetal antigen becomes exposed to the mother’s blood during the birth of the first child. The mother’s blood starts to synthesize D antibodies. But during subsequent pregnancies the Rh antibodies from the mother (Rh2) enters the foetal circulation and destroys the foetal RBCs. This becomes fatal to the foetus because the child suffers from anaemia and jaundice. This condition is called erythroblastosis foetalis. This condition can be avoided by administration of anti D antibodies (Rhocum) to the mother immediately after the first child birth.

Coagulation of Blood

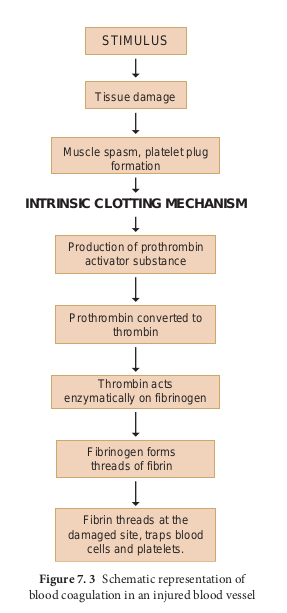

If you cut your finger or when you get yourself hurt, your wound bleeds for some time after which it stops to bleed. This is because the blood clots or coagulates in response to trauma. The mechanism by which excessive blood loss is prevented by the formation of clot is called blood coagulation or clotting of blood. Schematic representation of blood coagulation is shown Figure 7.3. The clotting process begins when the endothelium of the blood vessel is damaged and the connective tissue in its wall is exposed to the blood. Platelets adhere to collagen fibres in the connective tissue and release substances that form the platelet plug which provides emergency protection against blood loss. Clotting factors released from the clumped platelets or damaged cells mix with clotting factors in the plasma. The protein called prothrombin is converted to its active form called thrombin in the presence of calcium and vitamin K. Thrombin helps in the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin threads. The threads of fibrins become interlinked into a patch that traps blood cell and seals the injured vessel until the wound is healed. After sometime fibrin fibrils contract, squeezing out a straw-coloured fluid through a meshwork called serum (Plasma without fibrinogen is called serum). Heparin is an anticoagulant produced in small quantities by mast cells of connective tissue which prevents coagulation in small blood vessels.

Composition of Lymph and its Functions

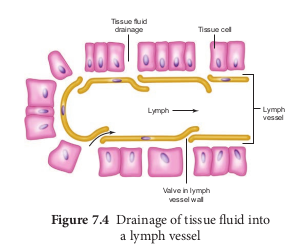

About 90% of fluid that leaks from capillaries eventually seeps back into the capillaries and the remaining 10% is collected and returned to blood system by means of a series of tubules known as lymph vessels or lymphatics. The fluid inside the lymphatics is called lymph. The lymphatic system consists of a complex network of thin walled ducts (lymphatic vessels), filtering bodies (lymph nodes) and a large number of lymphocytic cell concentrations in various lymphoid organs. The lymphatic vessels have smooth walls that run parallel to the blood vessels, in the skin, along the respiratory and digestive tracts. These vessels serve as return ducts for the fluids that are continually diffusing out of the blood capillaries into the body tissues. The end of a vessel is shown in Figure 7.4.

Lymph fluid must pass through the lymph nodes before it is returned to the blood. The lymph nodes that filter the fluid from the lymphatic vessels of the skin are highly concentrated in the neck, inguinal, axillaries, respiratory and digestive tracts. The lymph fluid flowing out of the lymph nodes flow into large collecting duct which finally drains into larger veins that runs beneath the collar bone, the subclavian vein and is emptied into the blood stream. The narrow passages in the lymph nodes are the sinusoids that are lined with macrophages. The lymph nodes successfully prevent the invading microorganisms from reaching the blood stream. Cells found in the lymphatics are the lymphocytes. Lymphocytes collected in the lymphatic fluid are carried via the arterial blood and are recycled back to the lymph. Fats are absorbed through lymph in the lacteals present in the villi of the intestinal wall.