In the last chapter we he we have explored arrays with only one dimension. It is also possible for arrays to have two or more dimensions. This chapter describes how multidimensional arrays can be created and manipulated in C.

Two-Dimensional Arrays The two-dimensional array is also called a matrix. Let us see how to create this array and work with it. Here is a sample program that stores roll number and marks obtained by a student side-by-side in a matrix.

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

int stud[ 4 ][ 2 ] ;

int i, j ;

for ( i = 0 ; i <= 3 ; i++ )

{

printf ( "Enter roll no. and marks" ) ;

scanf ( "%d %d", &stud[ i ][ 0 ], &stud[ i ][ 1 ] ) ;

}

for ( i = 0 ; i <= 3 ; i++ )

printf ( "%d %d\n", stud[ i ][ 0 ], stud[ i ][ 1 ] ) ;

return 0 ;

}

There are two parts to the program—in the first part, through a for loop, we read in the values of roll no. and marks, whereas, in the second part through another for loop, we print out these values.

Look at the scanf( ) statement used in the first for loop:

scanf ( “%d %d”, &stud[ i ][ 0 ], &stud[ i ][ 1 ] ) ;

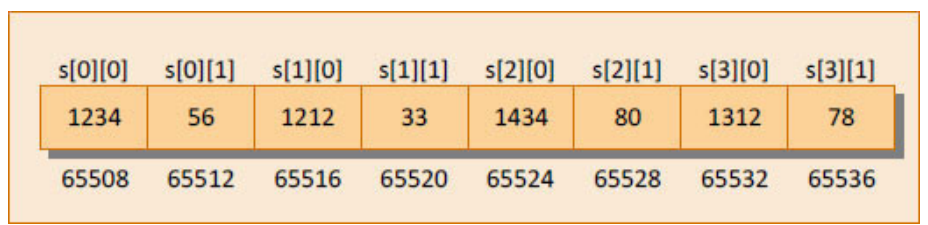

In stud[ i ][ 0 ] and stud[ i ][ 1 ], the first subscript of the variable stud, is row number which changes for every student. The second subscript tells which of the two columns are we talking about—the zeroth column which contains the roll no. or the first column which contains the marks. Remember the counting of rows and columns begin with zero. The complete array arrangement is shown in Figure 14.1.

column no. 0 column no. 1

row no. 0| 1234 | 56 |

row no. 1| 1212 | 33 |

row no. 2| 1434 | 80 |

row no. 3| 1312 | 78 |

Figure 14.1

Thus, 1234 is stored in stud[ 0 ][ 0 ], 56 is stored in stud[ 0 ][ 1 ] and so on. The above arrangement highlights the fact that a two- dimensional array is nothing but a collection of a number of one- dimensional arrays placed one below the other.

In our sample program, the array elements have been stored row-wise and accessed row-wise. However, you can access the array elements column-wise as well. Traditionally, the array elements are being stored and accessed row-wise; therefore we would also stick to the same strategy.

Initializing a Two-Dimensional Array

How do we initialize a two-dimensional array? As simple as this…

int stud[ 4 ][ 2 ] = { { 1234, 56 }, { 1212, 33 }, { 1434, 80 }, { 1312, 78 } } ;

or even this would work…

int stud[ 4 ][ 2 ] = { 1234, 56, 1212, 33, 1434, 80, 1312, 78 } ;

of course, with a corresponding loss in readability.

It is important to remember that, while initializing a 2-D array, it is necessary to mention the second (column) dimension, whereas the first dimension (row) is optional.

Thus the declarations,

int arr[ 2 ][ 3 ] = { 12, 34, 23, 45, 56, 45 } ;

int arr[ ][ 3 ] = { 12, 34, 23, 45, 56, 45 } ;

are perfectly acceptable,

whereas,

int arr[ 2 ][ ] = { 12, 34, 23, 45, 56, 45 } ; int arr[ ][ ] = { 12, 34, 23, 45, 56, 45 } ;

would never work.

Memory Map of a Two-Dimensional Array

Let us reiterate the arrangement of array elements in a two-dimensional array of students, which contains roll nos. in one column and the marks in the other.

The array arrangement shown in Figure 14.1 is only conceptually true. This is because memory doesn’t contain rows and columns. In memory, whether it is a one-dimensional or a two-dimensional array, the array elements are stored in one continuous chain. The arrangement of array elements of a two-dimensional array in memory is shown in Figure 14.2:

65508 65520 65524 65528

1234 56 1212 33 1434 80

65532 65536

1312 78

65512 65516

s[0][0] s[0][1] s[1][0] s[1][1] s[2][0] s[2][1] s[3][0] s[3][1]

Figure 14.2

We can easily refer to the marks obtained by the third student using the subscript notation as shown below.

printf ( "Marks of third student = %d", stud[ 2 ][ 1 ] ) ;

Can we not refer to the same element using pointer notation, the way we did in one-dimensional arrays? Answer is yes. Only the procedure is slightly difficult to understand. So, read on…

Pointers and Two-Dimensional Arrays

The C language embodies an unusual but powerful capability—it can treat parts of arrays as arrays. More specifically, each row of a two- dimensional array can be thought of as a one-dimensional array. This is a very important fact if we wish to access array elements of a two- dimensional array using pointers.

Thus, the declaration,

int s[ 5 ][ 2 ] ;

can be thought of as setting up an array of 5 elements, each of which is a one-dimensional array containing 2 integers. We refer to an element of a one-dimensional array using a single subscript. Similarly, if we can imagine s to be a one-dimensional array, then we can refer to its zeroth element as s[ 0 ], the next element as s[ 1 ] and so on. More specifically, s[ 0 ] gives the address of the zeroth one-dimensional array, s[ 1 ] gives the address of the first one-dimensional array and so on. This fact can be demonstrated by the following program:

/* Demo: 2-D array is an array of arrays */

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

int s[ 4 ][ 2 ] = { { 1234, 56 }, { 1212, 33 }, { 1434, 80 }, { 1312, 78 } } ;

int i ;

for ( i = 0 ; i <= 3 ; i++ )

printf ( "Address of %d th 1-D array = %u\n", i, s[ i ] ) ;

return 0 ;

}

And here is the output…

Address of 0 th 1-D array = 65508 Address of 1 th 1-D array = 65516 Address of 2 th 1-D array = 65524 Address of 3 th 1-D array = 65532

Let’s figure out how the program works. The compiler knows that s is an array containing 4 one-dimensional arrays, each containing 2 integers. Each one-dimensional array occupies 4 bytes (two bytes for each integer). These one-dimensional arrays are placed linearly (zeroth 1-D array followed by first 1-D array, etc.). Hence, each one-dimensional array starts 4 bytes further along than the last one, as can be seen in the memory map of the array shown in Figure 14.3.

65508 65520 65524 65528

1234 56 1212 33 1434 80

65532 65536

1312 78

65512 65516

s[0][0] s[0][1] s[1][0] s[1][1] s[2][0] s[2][1] s[3][0] s[3][1]

Figure 14.3

We know that the expressions s[ 0 ] and s[ 1 ] would yield the addresses of the zeroth and first one-dimensional array respectively. From Figure 14.3 these addresses turn out to be 65508 and 65516.

Now, we have been able to reach each one-dimensional array. What remains is to be able to refer to individual elements of a one- dimensional array. Suppose we want to refer to the element s[ 2 ][ 1 ] using pointers. We know (from the above program) that s[ 2 ] would give the address 65524, the address of the second one-dimensional array. Obviously ( 65524 + 1 ) would give the address 65528. Or ( s[ 2 ] + 1 ) would give the address 65528. And the value at this address can be obtained by using the value at address operator, saying *( s[ 2 ] + 1 ). But, we have already studied while learning one-dimensional arrays that num[ i ] is same as *( num + i ). Similarly, *( s[ 2 ] + 1 ) is same as, *( *( s + 2 ) + 1 ). Thus, all the following expressions refer to the same element:

s[ 2 ][ 1 ] * ( s[ 2 ] + 1 ) * ( * ( s + 2 ) + 1 )

Using these concepts, the following program prints out each element of a two-dimensional array using pointer notation:

/* Pointer notation to access 2-D array elements */

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

int s[ 4 ][ 2 ] = { { 1234, 56 }, { 1212, 33 }, { 1434, 80 }, { 1312, 78 } } ;

int i, j ;

for ( i = 0 ; i <= 3 ; i++ )

{

for ( j = 0 ; j <= 1 ; j++ )

printf ( "%d ", *( *( s + i ) + j ) ) ;

printf ( "\n" ) ;

}

return 0 ;

}

And here is the output…

1234 56 1212 33 1434 80 1312 78

Pointer to an Array

If we can have a pointer to an integer, a pointer to a float, a pointer to a char, then can we not have a pointer to an array? We certainly can. The following program shows how to build and use it:

/* Usage of pointer to an array */

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

int s[ 4 ][ 2 ] = { { 1234, 56 }, { 1212, 33 }, { 1434, 80 }, { 1312, 78 } } ;

int ( *p )[ 2 ] ;

int i, j, *pint ;

for ( i = 0 ; i <= 3 ; i++ )

{

p = &s[ i ];

pint = ( int * ) p ;

printf ( "\n" ) ;

for ( j = 0 ; j <= 1 ; j++ )

printf ( "%d ", *( pint + j ) ) ;

}

return 0 ;

}

And here is the output…

1234 56 1212 33 1434 80 1312 78

Here p is a pointer to an array of two integers. Note that the parentheses in the declaration of p are necessary. Absence of them would make p an array of 2 integer pointers. Array of pointers is covered in a later section in this chapter. In the outer for loop, each time we store the address of a new one-dimensional array. Thus first time through this loop, p would contain the address of the zeroth 1-D array. This address is then assigned to an integer pointer pint. Lastly, in the inner for loop using the pointer pint, we have printed the individual elements of the 1-D array to which p is pointing.

But why should we use a pointer to an array to print elements of a 2-D array. Is there any situation where we can appreciate its usage better? The entity pointer to an array is immensely useful when we need to pass a 2-D array to a function. This is discussed in the next section.

Passing 2-D Array to a Function

There are three ways in which we can pass a 2-D array to a function. These are illustrated in the following program:

/* Three ways of accessing a 2-D array */

# include <stdio.h>

void display ( int *q, int , int ) ;

void show ( int ( *q )[ 4 ], int, int ) ;

void print ( int q[ ][ 4 ], int , int ) ;

int main( )

{

int a[ 3 ][ 4 ] = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 0, 1, 6 } ;

display ( a, 3, 4 ) ;

show ( a, 3, 4 ) ;

print ( a, 3, 4 ) ;

return 0 ;

}

void display ( int *q, int row, int col )

{

int i, j ;

for ( i = 0 ; i < row ; i++ )

{

for ( j = 0 ; j < col ; j++ )

printf ( "%d ", *( q + i * col + j ) ) ;

printf ( "\n" ) ;

}

printf ("\n" ) ;

}

void show ( int ( *q )[ 4 ], int row, int col )

{

int i, j ;

int *p ;

for ( i = 0 ; i < row ; i++ )

{

p = q + i ;

for ( j = 0 ; j < col ; j++ )

printf ( "%d ", * ( p + j ) ) ;

printf ( "\n" ) ;

}

printf ( "\n" ) ;

}

void print ( int q[ ][ 4 ], int row, int col )

{

int i, j ;

for ( i = 0 ; i < row ; i++ )

{

for ( j = 0 ; j < col ; j++ )

printf ( "%d ", q[ i ][ j ] ) ;

printf ( "\n" ) ;

}

printf ( "\n" ) ;

}

And here is the output…

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 6

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 6

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 6

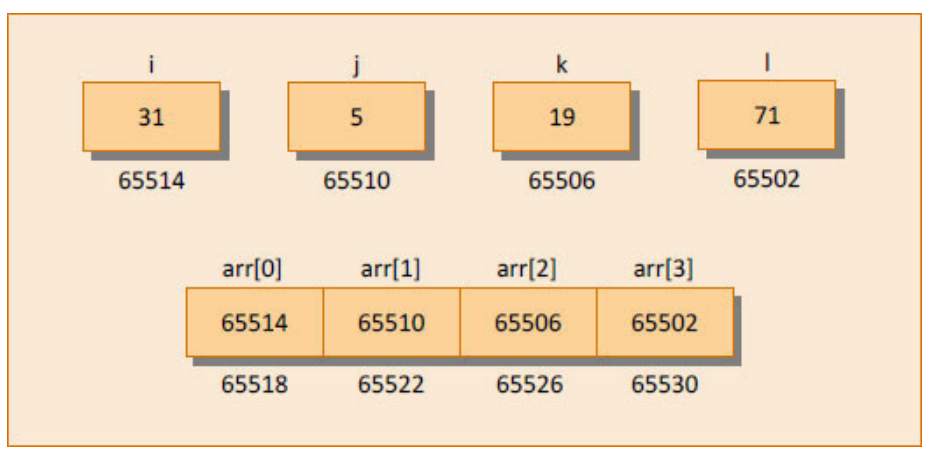

In the display( ) function, we have collected the base address of the 2-D array being passed to it in an ordinary int pointer. Then, through the two for loops using the expression ( q + i * col + j ), we have reached the appropriate element in the array. Suppose i is equal to 2 and j is equal to 3, then we wish to reach the element a[ 2 ][ 3 ]. Let us see whether the expression ( q + i * col + j ) does give this element or not. Refer Figure 14.4 to understand this.

Figure 14.4

The expression *** ( q + i * col + j )** becomes *** ( 65502 + 2 * 4 + 3). This turns out to be *** (65502 + 11 ). Since 65502 is the address of an integer, *** ( 65502 + 11 )** turns out to be * (65546). Value at this address is 6. This is indeed same as a[ 2 ][ 3 ]. A more general formula for accessing each array element would be:

- ( base address + row no. * no. of columns + column no. )

In the show( ) function, we have defined q to be a pointer to an array of 4 integers through the declaration:

int(*q)[4] ;

To begin with, q holds the base address of the zeroth 1-D array, i.e. 65502 (refer Figure 14.4). This address is then assigned to p, an int pointer, and then using this pointer, all elements of the zeroth 1-D array are accessed. Next time through the loop, when i takes a value 1, the expression q + i fetches the address of the first 1-D array. This is because, q is a pointer to zeroth 1-D array and adding 1 to it would give us the address of the next 1-D array. This address is once again assigned to p, and using it all elements of the next 1-D array are accessed.

In the third function print( ), the declaration of q looks like this:

int q[ ][ 4 ] ;

This is same as int ( *q )[ 4 ], where q is pointer to an array of 4 integers. The only advantage is that, we can now use the more familiar expression q[ i ][ j ] to access array elements. We could have used the same expression in show( ) as well.

Array of Pointers The way there can be an array of ints or an array of floats, similarly, there can be an array of pointers. Since a pointer variable always contains an address, an array of pointers would be nothing but a collection of addresses. The addresses present in the array of pointers can be addresses of isolated variables or addresses of array elements or any other addresses. All rules that apply to an ordinary array apply to the array of pointers as well. I think a program would clarify the concept.

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

int *arr[ 4 ] ; /* array of integer pointers */

int i = 31, j = 5, k = 19, l = 71, m ;

arr[ 0 ] = &i ;

arr[ 1 ] = &j ;

arr[ 2 ] = &k ;

arr[ 3 ] = &l ;

for ( m = 0 ; m <= 3 ; m++ )

printf ( "%d\n", *( arr[ m ] ) ) ;

return 0 ;

}

Figure 14.5 shows the contents and the arrangement of the array of pointers in memory. As you can observe, arr contains addresses of isolated int variables i, j, k and l. The for loop in the program picks up the addresses present in arr and prints the values present at these addresses.

Figure 14.5

An array of pointers can even contain the addresses of other arrays. The following program would justify this:

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

static int a[ ] = { 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 } ;

int *p[ ] = { a, a + 1, a + 2, a + 3, a + 4 } ;

printf ( "%u %u %d\n", p, *p, * ( *p ) ) ;

return 0 ;

}

I would leave it for you to figure out the output of this program.

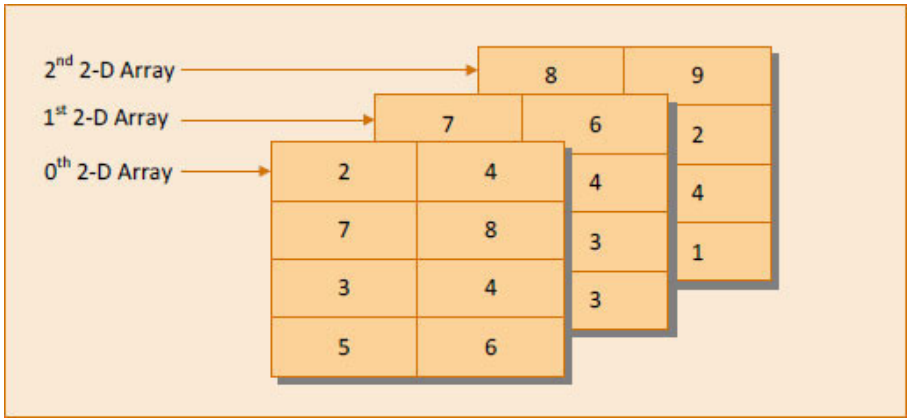

Three-Dimensional Array We aren’t going to show a programming example that uses a three- dimensional array. This is because, in practice, one rarely uses this array. However, an example of initializing a three-dimensional array will consolidate your understanding of subscripts.

int arr[ 3 ][ 4 ][ 2 ] = { { { 2, 4 }, { 7, 8 }, { 3, 4 }, { 5, 6 } }, { { 7, 6 }, { 3, 4 }, { 5, 3 }, { 2, 3 } }, { { 8, 9 }, { 7, 2 }, { 3, 4 }, { 5, 1 }, } } ;

A 3-D array can be thought of as an array of arrays of arrays. The outer array has three elements, each of which is a 2-D array of four 1-D arrays, each of which contains two integers. In other words, a 1-D array of two elements is constructed first. Then four such 1-D arrays are placed one below the other to give a 2-D array containing four rows. Then, three such 2-D arrays are placed one behind the other to yield a 3-D array containing three 2-D arrays. In the array declaration, note how the commas have been given. Figure 14.6 would possibly help you in visualizing the situation better.

Figure 14.6

Again remember that the arrangement shown above is only conceptually true. In memory, the same array elements are stored linearly as shown in Figure 14.7.

Figure 14.7

How would you refer to the array element 1 in the above array? The first subscript should be [ 2 ], since the element is in third two-dimensional array; the second subscript should be [ 3 ] since the element is in fourth row of the two-dimensional array; and the third subscript should be [ 1 ] since the element is in second position in the one-dimensional array. We can, therefore, say that the element 1 can be referred as arr[ 2 ][ 3 ][ 1 ]. It may be noted here that the counting of array elements even for a 3-D array begins with zero. Can we not refer to this element using pointer notation? Of course, yes. For example, the following two expressions refer to the same element in the 3-D array:

arr[ 2 ][ 3 ][ 1 ] *( *( *( arr + 2 ) + 3 ) + 1 )

Summary

-

It is possible to construct multidimensional arrays.

-

A 2-D array is a collection of several 1-D arrays.

-

A 3-D array is a collection of several 2-D arrays.

-

All elements of a 2-D or a 3-D array are internally accessed using pointers.

Exercise

[A] What will be the output of the following programs:

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

int n[ 3 ][ 3 ] = { 2, 4, 3, 6, 8, 5, 3, 5, 1 } ;

printf ( "%d %d %d\n", *n, n[ 3 ][ 3 ], n[ 2 ][ 2 ] ) ;

return 0 ;

}

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

int n[ 3 ][ 3 ] = { 2, 4, 3, 6, 8, 5, 3, 5, 1 } ;

int i, *ptr ;

ptr = n ;

for ( i = 0 ; i <= 8 ; i++ )

printf ( "%d\n", *( ptr + i ) ) ;

return 0 ;

}

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

int n[ 3 ][ 3 ] = { 2, 4, 3, 6, 8, 5, 3, 5, 1 } ;

int i, j ;

for ( i = 0 ; i <= 2 ; i++ )

for ( j = 0 ; j <= 2 ; j++ )

printf ( "%d %d\n", n[ i ][ j ], *( *( n + i ) + j ) ) ;

return 0 ;

}

[B] Point out the errors, if any, in the following programs:

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

int twod[ ][ ] = { 2, 4, 6, 8 } ;

printf ( "%d\n", twod ) ;

return 0 ;

}

# include <stdio.h>

int main( )

{

int three[ 3 ][ ] = { 2, 4, 3, 6, 8, 2, 2, 3, 1 } ;

printf ( "%d\n", three[ 1 ][ 1 ] ) ;

return 0 ;

}

[C] Attempt the following:

-

How will you initialize a three-dimensional array threed[ 3 ][ 2 ][ 3]? How will you refer the first and last element in this array?

-

Write a program to pick up the largest number from any 5 row by 5 column matrix.

-

Write a program to obtain transpose of a 4 x 4 matrix. The transpose of a matrix is obtained by exchanging the elements of each row with the elements of the corresponding column.

-

Very often in fairs we come across a puzzle that contains 15 numbered square pieces mounted on a frame. These pieces can be moved horizontally or vertically. A possible arrangement of these pieces is shown in Figure 14.8:

1 4 15 7

8 10 2 11

14 3 6 13

12 9 5

Figure 14.8

As you can see there is a blank at bottom right corner. Implement the following procedure through a program:

Draw the boxes as shown above. Display the numbers in the above order. Allow the user to hit any of the arrow keys (up, down, left, or right). If you are using Turbo C/C++, use the library function gotoxy( ) to position the cursor on the screen while drawing the boxes. If you are using Visual Studio then use the following function to position the cursor:

#include <windows.h>

void gotoxy ( short col, short row )

{

HANDLE h = GetStdHandle ( STD\_OUTPUT\_HANDLE ) ;

COORD position = { col, row } ;

SetConsoleCursorPosition ( h, position ) ;

}

If user hits say, right arrow key then the piece with a number 5 should move to the right and blank should replace the original

position of 5. Similarly, if down arrow key is hit, then 13 should move down and blank should replace the original position of 13. If left arrow key or up arrow key is hit then no action should be taken.

The user would continue hitting the arrow keys till the numbers aren’t arranged in ascending order.

Keep track of the number of moves in which the user manages to arrange the numbers in ascending order. The user who manages it in minimum number of moves is the one who wins.

How do we tackle the arrow keys? We cannot receive them using scanf( ) function. Arrow keys are special keys which are identified by their ‘scan codes’. Use the following function in your program. It would return the scan code of the arrow key being hit. The scan codes for the arrow keys are:

up arrow key – 72 down arrow key – 80 left arrow key – 75 right arrow key – 77

# include <conio.h>

int getkey( )

{

int ch ;

ch = getch( ) ;

if ( ch == 0 )

{

ch = getch( ) ;

return ch ;

}

return ch ;

}

- Match the following with reference to the program segment given below:

int i, j, = 25;

int *pi, *pj = & j; ……. ……. /* more lines of program */ …….

*pj = j + 5;

j = *pj + 5 ;

pj = pj ;

*pi = i + j

Each integer quantity occupies 2 bytes of memory. The value assigned to i begin at (hexadecimal) address F9C and the value assigned to j begins at address F9E. Match the value represented by left hand side quantities with the right.

1. &i a. 30

2. &j b. F9E

3. pj c. 35

4. *pj d. FA2

5. i e. F9C

6. pi f. 67

7. *pi g. unspecified

8. ( pi + 2 ) h. 65

9. (*pi + 2) i. F9E

10. *( pi + 2 ) j. F9E

k. FAO l. F9D

- Match the following with reference to the following program segment:

int x[ 3 ][ 5 ] = { { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }, { 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 }, { 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 } }, *n = &x ;

1. *( *( x + 2 ) + 1) a. 9

2. *( *x + 2 ) + 5 b. 13

3. *( *( x + 1) ) c. 4

4. *( *( x ) + 2 ) + 1 d. 3

5. * ( *( x + 1 ) + 3 ) e. 2

6. *n f. 12

7. *( n +2 ) g. 14

8. (*(n + 3 ) + 1 h. 7

9. *(n + 5)+1 i. 1

10. ++*n j. 8

k. 5 l. 10 m. 6

- Match the following with reference to the following program segment:

unsigned int arr[ 3 ][ 3 ] = { 2, 4, 6, 9, 1, 10, 16, 64, 5 } ;

1. **arr a. 64

2. **arr < *( *arr + 2 ) b. 18

3. *( arr + 2 ) / ( *( *arr + 1 ) > **arr ) c. 6

4. *( arr[ 1 ] + 1 ) | arr[ 1 ][ 2 ] d. 3

5. *( arr[ 0 ] ) | *( arr[ 2 ] ) e. 0

6. arr[ 1 ][ 1 ] < arr[ 0 ][ 1 ] f. 16

7. arr[ 2 ][ 1 ] & arr[ 2 ][ 0 ] g. 1

8. arr[ 2 ][ 2 ] | arr[ 0 ][ 1 ] h. 11

9. arr[ 0 ][ 1 ] ^ arr[ 0 ][ 2 ] i. 20

10. ++**arr + --arr[ 1 ][ 1 ] j. 2

k. 5 l. 4

-

Write a program to find if a square matrix is symmetric.

-

Write a program to add two 6 x 6 matrices.

-

Write a program to multiply any two 3 x 3 matrices.

-

Given an array p[ 5 ], write a function to shift it circularly left by two positions. Thus, if p[ 0 ] = 15, p[ 1 ]= 30, p[ 2 ] = 28, p[ 3 ]= 19 and p[ 4 ] = 61 then after the shift p[ 0 ] = 28, p[ 1 ] = 19, p[ 2 ] = 61, p[ 3 ] = 15 and p[ 4 ] = 30. Call this function for a (4 x 5 ) matrix and get its rows left shifted.

-

A 6 x 6 matrix is entered through the keyboard. Write a program to obtain the Determinant value of this matrix.

(m) For the following set of sample data, compute the standard deviation and the mean.

-6, -12, 8, 13, 11, 6, 7, 2, -6, -9, -10, 11, 10, 9, 2

The formula for standard deviation is

_n_

_xxi_

- (

where x i is the data item and x is the mean.

(n) The area of a triangle can be computed by the sine law when 2 sides of the triangle and the angle between them are known.

Area = (1 / 2 ) ab sin ( angle )

Given the following 6 triangular pieces of land, write a program to find their area and determine which is largest.

Plot No. a b angle

1 137.4 80.9 0.78 2 155.2 92.62 0.89 3 149.3 97.93 1.35 4 160.0 100.25 9.00 5 155.6 68.95 1.25 6 149.7 120.0 1.75

(o) For the following set of n data points (x, y), compute the correlation coefficient r, given by

x y 34.22 102.43 39.87 100.93 41.85 97.43 43.23 97.81 40.06 98.32 53.29 98.32 53.29 100.07 54.14 97.08 49.12 91.59 40.71 94.85 55.15 94.65

(p) For the following set of point given by (x, y) fit a straight line given by y = a + bx

where,

and

-

])([])([ 2222 yynxxn

yxxy r

xb y_a_

-

])([ 22 xxn

yxyxn b

x Y 3.0 1.5 4.5 2.0 5.5 3.5 6.5 5.0 7.5 6.0 8.5 7.5 8.0 9.0 9.0 10.5 9.5 12.0 10.0 14.0

(q) The X and Y coordinates of 10 different points are entered through the keyboard. Write a program to find the distance of last point from the first point (sum of distances between consecutive points).

(r) A dequeue is an ordered set of elements in which elements may be inserted or retrieved from either end. Using an array simulate a dequeue of characters and the operations retrieve left, retrieve right, insert left, insert right. Exceptional conditions such as dequeue full or empty should be indicated. Two pointers (namely, left and right) are needed in this simulation.

(s) Sudoku is a popular number-placement puzzle (refer Figure 14.9). The objective is to fill a 9×9 grid with digits so that each column, each row, and each of the nine 3×3 sub-grids that compose the grid contains all of the digits from 1 to 9. The puzzle setter provides a partially completed grid, which typically has a unique solution. One such solution is given below. Write a program to check whether the solution is correct or not.

5 3 4 6

6 7 2 1

1 9 8 3

8 5 9 7

7 8 9 1

9 5 3 4

4 2 5 6

6 1 4 2

2

8

7

3

4 2 6 8

7 1 3 9

9 6 1 5

2 8 7 4

5 3 7 9

2 4 8 5

3 7 2 8

1 9 6 3

1

6

4

5

3 4 5 2 8 6 1 7 9

Figure 14.9