The C language provides a capability that enables the user to design a set of similar data types, called array. This chapter describes how arrays can be created and manipulated in C.

We should note that, in many C books and courses, arrays and pointers are taught separately. I feel it is worthwhile to deal with these topics together. This is because pointers and arrays are so closely related that discussing arrays without discussing pointers would make the discussion incomplete and wanting. In fact, all arrays make use of pointers internally. Hence, it is all too relevant to study them together rather than as isolated topics.

What are Arrays? For understanding the arrays properly, let us consider the following program:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

int x;

x = 5;

x = 10;

printf("x = %d\n", x);

return 0;

}

No doubt, this program will print the value of x as 10. Why so? Because, when a value 10 is assigned to x, the earlier value of x, i.e., 5 is lost. Thus, ordinary variables(the ones which we have used so far) are capable of holding only one value at a time(as in this example). However, there are situations in which we would want to store more than one value at a time in a single variable.

For example, suppose we wish to arrange the percentage marks obtained by 100 students in ascending order. In such a case, we have two options to store these marks in memory:

-

Construct 100 variables to store percentage marks obtained by 100 different students, i.e., each variable containing one student’s marks.

-

Construct one variable(called array or subscripted variable) capable of storing or holding all the hundred values.

Obviously, the second alternative is better. A simple reason for this is, it would be much easier to handle one variable than handling 100 different variables. Moreover, there are certain logics that cannot be dealt with, without the use of an array. Now a formal definition of an array—An array is a collective name given to a group of ‘similar quantities’. These similar quantities could be percentage marks of 100 students, or salaries of 300 employees, or ages of 50 employees. What is important is that the quantities must be ‘similar’. Each member in the group is referred to by its position in the group. For example, assume the following group of numbers, which represent percentage marks obtained by five students.

per = { 48, 88, 34, 23, 96 }

If we want to refer to the second number of the group, the usual notation used is per2. Similarly, the fourth number of the group is referred as per4. However, in C, the fourth number is referred as per[3]. This is because, in C, the counting of elements begins with 0 and not with 1. Thus, in this example per[3] refers to 23 and per[4] refers to 96. In general, the notation would be per[i], where, i can take a value 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4, depending on the position of the element being referred. Here per is the subscripted variable(array), whereas i is its subscript.

Thus, an array is a collection of similar elements. These similar elements could be all ints, or all floats, or all chars, etc. Usually, the array of characters is called a ‘string’, whereas an array of ints or floats is called simply an array. Remember that all elements of any given array must be of the same type, i.e., we cannot have an array of 10 numbers, of which 5 are ints and 5 are floats.

A Simple Program using Array

Let us try to write a program to find average marks obtained by a class of 30 students in a test.

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

int avg,sum = 0;

int i;

int marks[30]; /* array declaration */

for(i = 0; i <= 29; i++)

{

printf("Enter marks");

scanf("%d", &marks[i]); /* store data in array */

}

for(i = 0; i <= 29; i++)

sum = sum + marks[i]; /* read data from an array*/

avg = sum / 30;

printf("Average marks = %d\n", avg);

return 0;

}

There is a lot of new material in this program, so let us take it apart slowly.

Array Declaration

To begin with, like other variables, an array needs to be declared so that the compiler will know what kind of an array and how large an array we want. In our program, we have done this with the statement:

int marks[30];

Here, int specifies the type of the variable, just as it does with ordinary variables and the word marks specifies the name of the variable. The [30] however is new. The number 30 tells how many elements of the type int will be in our array. This number is often called the ‘dimension’ of the array. The bracket([]) tells the compiler that we are dealing with an array.

Accessing Elements of an Array

Once an array is declared, let us see how individual elements in the array can be referred. This is done with subscript, the number in the brackets following the array name. This number specifies the element’s position in the array. All the array elements are numbered, starting with 0. Thus, marks[2] is not the second element of the array, but the third. In our program, we are using the variable i as a subscript to refer to various elements of the array. This variable can take different values and hence can refer to the different elements in the array in turn. This ability to use variables to represent subscripts is what makes arrays so useful.

Entering Data into an Array

Here is the section of code that places data into an array:

for(i = 0; i <= 29; i++)

{

printf("Enter marks");

scanf("%d", &marks[i]);

}

The for loop causes the process of asking for and receiving a student’s marks from the user to be repeated 30 times. The first time through the loop, i has a value 0, so the scanf() function will cause the value typed to be stored in the array element marks[0], the first element of the array. This process will be repeated until i becomes 29. This is last time through the loop, which is a good thing, because there is no array element like marks[30].

In scanf() function, we have used the “address of” operator(&) on the element marks[i] of the array, just as we have used it earlier on other variables (&rate, for example). In so doing, we are passing the address of this particular array element to the scanf() function, rather than its value; which is what scanf() requires.

Reading Data from an Array

The balance of the program reads the data back out of the array and uses it to calculate the average. The for loop is much the same, but now the body of the loop causes each student’s marks to be added to a running total stored in a variable called sum. When all the marks have been added up, the result is divided by 30, the number of students, to get the average.

for(i = 0; i <= 29; i++)

sum = sum + marks[i];

avg = sum / 30;

printf("Average marks = %d\n", avg);

To fix our ideas, let us revise whatever we have learnt about arrays:

-

An array is a collection of similar elements.(b) The first element in the array is numbered 0, so the last element is 1 less than the size of the array.

-

An array is also known as a subscripted variable.(d) Before using an array, its type and dimension must be declared.(e) However big an array, its elements are always stored in contiguous

memory locations. This is a very important point which we would discuss in more detail later on.

More on Arrays Array is a very popular data type with C programmers. This is because of the convenience with which arrays lend themselves to programming. The features which make arrays so convenient to program would be discussed below, along with the possible pitfalls in using them.

Array Initialization

So far we have used arrays that did not have any values in them to begin with. We managed to store values in them during program execution. Let us now see how to initialize an array while declaring it. Following are a few examples that demonstrate this:

int num[6] = { 2, 4, 12, 5, 45, 5 };

int n[] = { 2, 4, 12, 5, 45, 5 };

float press[] = { 12.3, 34.2, -23.4, -11.3 };

Note the following points carefully:

-

Till the array elements are not given any specific values, they are supposed to contain garbage values.

-

If the array is initialised where it is declared, mentioning the dimension of the array is optional as in the 2nd and 3rd examples above.

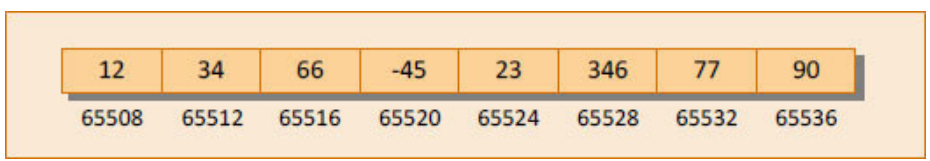

Array Elements in Memory

Consider the following array declaration:

int arr[8];

What happens in memory when we make this declaration? 32 bytes get immediately reserved in memory, 4 bytes each for the 8 integers(under TC/TC++ the array would occupy 16 bytes as each integer would occupy 2 bytes). And since the array is not being initialized, all eight values present in it would be garbage values. This so happens because the storage class of this array is assumed to be auto. If the storage class is declared to be static, then all the array elements would have a default

initial value as zero. Whatever be the initial values, all the array elements would always be present in contiguous memory locations. This arrangement of array elements in memory is shown in Figure 13.1.

Figure 13.1

Bounds Checking

In C, there is no check to see if the subscript used for an array exceeds the size of the array. Data entered with a subscript exceeding the array size will simply be placed in memory outside the array; probably on top of other data, or on the program itself. This will lead to unpredictable results, to say the least, and there will be no error message to warn you that you are going beyond the array size. In some cases, the computer may just hang. Thus, the following program may turn out to be suicidal:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

int num[40], i;

for(i = 0; i <= 100; i++)

num[i] = i;

return 0;

}

Thus, to see to it that we do not reach beyond the array size, is entirely the programmer’s botheration and not the compiler’s.

Passing Array Elements to a Function

Array elements can be passed to a function by calling the function by value, or by reference. In the call by value, we pass values of array elements to the function, whereas in the call by reference, we pass addresses of array elements to the function. These two calls are illustrated below.

/* Demonstration of call by value */

#include <stdio.h>

void display(int);

int main()

{

int i;

int marks[] = { 55, 65, 75, 56, 78, 78, 90 };

for(i = 0; i <= 6; i++)

display(marks[i]);

return 0;

}

void display(int m)

{

printf("%d", m);

}

And here’s the output…

55 65 75 56 78 78 90

Here, we are passing an individual array element at a time to the function display() and getting it printed in the function display(). Note that, since at a time only one element is being passed, this element is collected in an ordinary integer variable m, in the function display().

And now the call by reference.

/* Demonstration of call by reference */

#include <stdio.h>

void disp(int *);

int main()

{

int i;

int marks[] = { 55, 65, 75, 56, 78, 78, 90 };

for(i = 0; i <= 6; i++)

disp(&marks[i]);

return 0;

}

void disp(int *n)

{

printf("%d", *n);

}

And here’s the output…

55 65 75 56 78 78 90

Here, we are passing addresses of individual array elements to the function disp(). Hence, the variable in which this address is collected(n), is declared as a pointer variable. And since n contains the address of array element, to print out the array element, we are using the ‘value at address’ operator (*).

Read the following program carefully. The purpose of the function disp() is just to display the array elements on the screen. The program is only partly complete. You are required to write the function show() on your own. Try your hand at it.

#include <stdio.h>

void disp(int *);

int main()

{

int i;

int marks[] = { 55, 65, 75, 56, 78, 78, 90 };

for(i = 0; i <= 6; i++)

disp(&marks[i]);

return 0;

}

void disp(int *n)

{

show(&n);

}

Pointers and Arrays To be able to see what pointers have got to do with arrays, let us first learn some pointer arithmetic. Consider the following example:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i = 3, *x;

float j = 1.5, *y;

char k = 'c', *z;

printf("Value of i = %d\n", i);

printf("Value of j = %f\n", j);

printf("Value of k = %c\n", k);

x = &i;

y = &j;

z = &k;

printf("Original address in x = %u\n", x);

printf("Original address in y = %u\n", y);

printf("Original address in z = %u\n", z);

x++;

y++;

z++;

printf("New address in x = %u\n", x);

printf("New address in y = %u\n", y);

printf("New address in z = %u\n", z);

return 0;

}

Here is the output of the program.

Value of i = 3

Value of j = 1.500000

Value of k = c

Original address in x = 65524

Original address in y = 65520

Original address in z = 65519

New address in x = 65528

New address in y = 65524

New address in z = 65520

Observe the last three lines of the output. 65528 is original value in x plus 4, 65524 is original value in y plus 4, and 65520 is original value in z plus 1. This so happens because every time a pointer is incremented, it points to the immediately next location of its type. That is why, when the integer pointer x is incremented, it points to an address four locations after the current location, since an int is always 4 bytes long(under TC/TC++, since int is 2 bytes long, new value of x would be 65526). Similarly, y points to an address 4 locations after the current location and z points 1 location after the current location. This is a very important result and can be effectively used while passing the entire array to a function.

The way a pointer can be incremented, it can be decremented as well, to point to earlier locations. Thus, the following operations can be performed on a pointer:

- Addition of a number to a pointer. For example,

int i = 4, *j, *k;

j = &i;

j = j + 1;

j = j + 9;

k = j + 3;

- Subtraction of a number from a pointer. For example,

int i = 4, *j, *k;

j = &i;

j = j - 2;

j = j - 5;

k = j - 6;

- Subtraction of one pointer from another.

One pointer variable can be subtracted from another provided both variables point to elements of the same array. The resulting value indicates the number of elements separating the corresponding array elements. This is illustrated in the following program:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int arr[] = { 10, 20, 30, 45, 67, 56, 74 };

int *i, *j;

i = &arr[1];

j = &arr[5];

printf("%d %d\n", j - i, *j - *i);

return 0;

}

Here i and j have been declared as integer pointers holding addresses of first and fifth element of the array, respectively.

Suppose the array begins at location 65502, then the elements arr[1] and arr[5] would be present at locations 65506 and 65522 respectively, since each integer in the array occupies 2 bytes in memory. The expression j - i would print a value 4 and not 8. This is because j and i are pointing to locations that are 4 integers apart. What will be the result of the expression **j - i? 36, since *j and *i return the values present at addresses contained in the pointers j and i.

- Comparison of two pointer variables

Pointer variables can be compared provided both variables point to objects of the same data type. Such comparisons can be useful when both pointer variables point to elements of the same array. The comparison can test for either equality or inequality. Moreover, a pointer variable can be compared with zero(usually expressed as NULL). The following program illustrates how the comparison is carried out:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int arr[] = { 10, 20, 36, 72, 45, 36 };

int *j, *k;

j = &arr[4];

k = (arr + 4);

if (j == k)

printf("The two pointers point to the same location\n");

else

printf("The two pointers do not point to the same location\n");

return 0;

}

A word of caution! Do not attempt the following operations on pointers… they would never work out.

- Addition of two pointers(b) Multiplication of a pointer with a constant(c) Division of a pointer with a constant

Now we will try to correlate the following two facts, which we have learnt above:

- Array elements are always stored in contiguous memory locations.(b) A pointer when incremented always points to an immediately next

location of its type.

Suppose we have an array **num[]** = { 24, 34, 12, 44, 56, 17 }. Figure 13.2 shows how this array is located in memory.

Figure 13.2

Here is a program that prints out the memory locations in which the elements of this array are stored.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int num[] = { 24, 34, 12, 44, 56, 17 };

int i;

for (i = 0; i <= 5; i++) {

printf("element no. %d", i);

printf("address = %u\n", &num[i]);

}

return 0;

}

The output of this program would look like this:

element no. 0

address = 65512

element no. 1

address = 65516

element no. 2

address = 65520

element no. 3

address = 65524

element no. 4

address = 65528

element no. 5

address = 65532

Note that the array elements are stored in contiguous memory locations, each element occupying 2 bytes, since it is an integer array. When you run this program, you may get different addresses, but what is certain is that each subsequent address would be 4 bytes(2 bytes in Turbo C/C++) greater than its immediate predecessor.

Our next two programs show ways in which we can access the elements of this array.

#include <stdio.h> int main()

{ int num[] = { 24, 34, 12, 44, 56, 17 };

int i;

for(i = 0; i <= 5; i++)

{

printf("address = %u", &num[i]);

printf("element = %d\n", num[i]);

} return 0;

}

The output of this program would be:

address = 65512 element = 24 address = 65516 element = 34 address = 65520 element = 12 address = 65524 element = 44 address = 65528 element = 56 address = 65532 element = 17

This method of accessing array elements by using subscripted variables is already known to us. This method has, in fact, been given here for easy comparison with the next method, which accesses the array elements using pointers.

#include <stdio.h> int main()

{ int num[] = { 24, 34, 12, 44, 56, 17 };

int i, *j;

j = &num[0]; /* assign address of zeroth element */

for(i = 0; i <= 5; i++)

{

printf("address = %u", j);

printf("element = %d\n", *j);

j++; /* increment pointer to point to next location */ }

return 0;

}

The output of this program would be:

address = 65512 element = 24 address = 65516 element = 34 address = 65520 element = 12 address = 65524 element = 44 address = 65528 element = 56 address = 65532 element = 17

In this program, to begin with, we have collected the base address of the array(address of the 0th element) in the variable j using the statement,

j = &num[0]; /* assigns address 65512 to j */

When we are inside the loop for the first time, j contains the address 65512, and the value at this address is 24. These are printed using the statements,

printf(“address = %u”, j); printf(“element = %d\n”, *j);

On incrementing j, it points to the next memory location of its type(that is location no. 65516). But location no. 65516 contains the second element of the array, therefore when the printf() statements are executed for the second time, they print out the second element of the array and its address(i.e., 34 and 65516)… and so on till the last element of the array has been printed.

Obviously, a question arises as to which of the above two methods should be used when? Accessing array elements by pointers is always faster than accessing them by subscripts. However, from the point of view of convenience in programming, we should observe the following:

Array elements should be accessed using pointers, if the elements are to be accessed in a fixed order, say from beginning to end, or from end to beginning, or every alternate element or any such definite logic.

Instead, it would be easier to access the elements using a subscript if there is no fixed logic in accessing the elements. However, in this case also, accessing the elements by pointers would work faster than subscripts.

Passing an Entire Array to a Function

In the previous section, we saw two programs—one in which we passed individual elements of an array to a function, and another in which we passed addresses of individual elements to a function. Let us now see how to pass an entire array to a function rather than its individual elements. Consider the following example:

/* Demonstration of passing an entire array to a function */ #include <stdio.h>

void display(int *, int);

int main()

{

int num[] = { 24, 34, 12, 44, 56, 17 };

dislpay(&num[0], 6);

return 0;

}

void display(int *j, int n)

{

int i; for(i = 0; i <= n - 1; i++)

{

printf("element = %d\n", *j); j++; /* increment pointer to point to next element */ }

}

Here, the display() function is used to print out the array elements. Note that the address of the zeroth element is being passed to the display() function. The for loop is same as the one used in the earlier program to access the array elements using pointers. Thus, just passing the address of the zeroth element of the array to a function is as good as passing the entire array to the function. It is also necessary to pass the total number of elements in the array, otherwise the display() function

would not know when to terminate the for loop. Note that the address of the zeroth element(many a time called the base address) can also be passed by just passing the name of the array. Thus, the following two function calls are same:

display(&num[0], 6); display(num, 6);

The Real Thing

If you have grasped the concept of storage of array elements in memory and the arithmetic of pointers, here is some real food for thought. Once again consider the following array:

65512 65516 65520 65524 65528 65532

24 34 12 44 56 17

Figure 13.3

This is how we would declare the above array in C,

int num[] = { 24, 34, 12, 44, 56, 17 };

We also know, that on mentioning the name of the array, we get its base address. Thus, by saying *num, we would be able to refer to the zeroth element of the array, that is, 24. One can easily see that *num and *(num + 0) both refer to 24.

Similarly, by saying *(num + 1), we can refer the first element of the array, that is, 34. In fact, this is what the C compiler does internally. When we say, num[i], the C compiler internally converts it to *(num + i). This means that all the following notations are same:

num[i] *(num + i) *(i + num) i[num]

And here is a program to prove my point.

/* Accessing array elements in different ways */ #include <stdio.h> int main()

{

int num[] = { 24, 34, 12, 44, 56, 17 };

int i; for(i = 0; i <= 5; i++)

{

printf("address = %u", &num[i]);

printf("element = %d %d", num[i], *(num + i)); printf("%d %d\n", *(i + num), i[num]);

}

return 0;

}

The output of this program would be:

address = 65512 element = 24 24 24 24 address = 65516 element = 34 34 34 34 address = 65520 element = 12 12 12 12 address = 65524 element = 44 44 44 44 address = 65528 element = 56 56 56 56 address = 65532 element = 17 17 17 17

Summary

-

An array is similar to an ordinary variable except that it can store multiple elements of similar type.

-

Compiler doesn’t perform bounds checking on an array.

-

The array variable acts as a pointer to the zeroth element of the array. In a 1-D array, zeroth element is a single value, whereas, in a 2-D array this element is a 1-D array.

-

On incrementing a pointer it points to the next location of its type.

-

Array elements are stored in contiguous memory locations and so they can be accessed using pointers.

-

Only limited arithmetic can be done on pointers.

Exercise

[A] What will be the output of the following programs:

- #include <stdio.h> int main() { int num[26], temp; num[0] = 100; num[25] = 200; temp = num[25]; num[25] = num[0]; num[0] = temp; printf("%d %d\n", num[0], num[25]); return 0; }

- #include <stdio.h> int main() { int array[26], i; for(i = 0; i <= 25; i++) { array[i] = 'A' + i; printf("%d %c\n", array[i], array[i]); } return 0; }

- #include <stdio.h> int main() { int sub[50], i; for(i = 0; i <= 48; i++); { sub[i] = i; printf("%d\n", sub[i]); } return 0; }

[B] Point out the errors, if any, in the following program segments:

- /* mixed has some char and some int values */

#include <stdio.h> int char mixed[100]; int main() { int a[10], i; for(i = 1; i <= 10; i++) { scanf("%d", a[i]); printf("%d\n", a[i]); } return 0; }

- #include <stdio.h> int main() { int size; scanf("%d", &size); int arr[size]; for(i = 1; i <= size; i++) { scanf("%d", &arr[i]); printf("%d\n", arr[i]); } return 0; }

- #include <stdio.h> int main() { int i, a = 2, b = 3; int arr[2 + 3]; for(i = 0; i < a+b; i++) { scanf("%d", &arr[i]); printf("%d\n", arr[i]); } return 0; }

[C] Answer the following:

- An array is a collection of:

1. Different data types scattered throughout memory 2. The same data type scattered throughout memory 3. The same data type placed next to each other in memory 4. Different data types placed next to each other in memory

- Are the following array declarations correct?

int a(25); int size = 10, b[size]; int c = { 0,1,2 };

- Which element of the array does this expression reference?

num[4]

- What is the difference between the 5’s in these two expressions?(Select the correct answer)

int num[5]; num[5] = 11;

1. First is particular element, second is type 2. First is array size, second is particular element 3. First is particular element, second is array size 4. Both specify array size

- State whether the following statements are True or False:

1. The array int num[26] has twenty-six elements. 2. The expression num[1] designates the first element in the

array. 3. It is necessary to initialize the array at the time of declaration. 4. The expression num[27] designates the twenty-eighth element

in the array.

[D] Attempt the following:

-

Twenty-five numbers are entered from the keyboard into an array. The number to be searched is entered through the keyboard by the user. Write a program to find if the number to be searched is present in the array and if it is present, display the number of times it appears in the array.

-

Implement the Selection Sort, Bubble Sort and Insertion sort algorithms on a set of 25 numbers.(Refer Figures 13.4(a), 13.4(b), 13.4(c) for the logic of the algorithms)

Figure 13.4(c)

- Implement in a program the following procedure to generate prime numbers from 1 to 100. This procedure is called sieve of Eratosthenes.

Step 1 Fill an array num[100] with numbers from 1 to 100.

Step 2 Starting with the second entry in the array, set all its multiples to zero.

Step 3 Proceed to the next non-zero element and set all its multiples to zero.

Step 4 Repeat Step 3 till you have set up the multiples of all the non-zero elements to zero.

Step 5 At the conclusion of Step 4, all the non-zero entries left in the array would be prime numbers, so print out these numbers.

-

Twenty-five numbers are entered from the keyboard into an array. Write a program to find out how many of them are positive, how many are negative, how many are even and how many odd.

-

Write a program that interchanges the odd and even elements of an array.

[E] What will be the output of the following programs:

- #include <stdio.h> int main()

{ int b[] = { 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 }; int i; for(i = 0; i <= 4; i++) printf("%d\n" *(b + i)); return 0; }

-

#include <stdio.h> int main() { int b[] = { 0, 20, 0, 40, 5 }; int i, *k; k = b; for(i = 0; i <= 4; i++) { printf("%d\n" *k); k++; } return 0; }

-

#include <stdio.h> void change(int *, int); int main() { int a[] = { 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 }; int i; change(a, 5); for(i = 0; i <= 4; i++) printf("%d\n", a[i]); return 0; } void change(int *b, int n) { int i; for(i = 0; i < n; i++) *(b + i) = *(b + i) + 5; }

-

#include <stdio.h> int main()

{ static int a[5]; int i; for(i = 0; i <= 4; i++) printf("%d\n", a[i]); return 0; }

- #include <stdio.h> int main() { int a[5] = { 5, 1, 15, 20, 25 }; int i, j, k = 1, m; i = ++a[1]; j = a[1]++; m = a[i++]; printf("%d %d %d\n", i, j, m); }

[F] Point out the errors, if any, in the following programs:

-

#include <stdio.h> int main() { int array[6] = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 }; int i; for(i = 0; i <= 25; i++) printf("%d\n", array[i]); return 0; }

-

#include <stdio.h> int main() { int sub[50], i; for(i = 1; i <= 50; i++) { sub[i] = i; printf("%d\n" , sub[i]); } return 0; }

-

#include <stdio.h>

int main() { int a[] = { 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 }; int j; j = a; /* store the address of zeroth element */ j = j + 3; printf("%d\n" *j); return 0; }

-

#include <stdio.h> int main() { float a[] = { 13.24, 1.5, 1.5, 5.4, 3.5 }; float *j; j = a; j = j + 4; printf("%d %d %d\n", j, *j, a[4]); return 0; }

-

#include <stdio.h> int main() { int max = 5; float arr[max]; for(i = 0; i < max; i++) scanf("%f", &arr[i]); return 0; }

[G] Answer the following:

- What will happen if you try to put so many values into an array when you initialize it that the size of the array is exceeded?

1. Nothing 2. Possible system malfunction 3. Error message from the compiler 4. Other data may be overwritten

-

In an array int arr[12] the word arr represents the a_________ of the array.

-

What will happen if you put too few elements in an array when you initialize it?

1. Nothing 2. Possible system malfunction 3. Error message from the compiler 4. Unused elements will be filled with 0’s or garbage

- What will happen if you assign a value to an element of an array whose subscript exceeds the size of the array?

1. The element will be set to 0 2. Nothing, it’s done all the time 3. Other data may be overwritten 4. Error message from the compiler

- When you pass an array as an argument to a function, what actually gets passed?

1. Address of the array 2. Values of the elements of the array 3. Address of the first element of the array 4. Number of elements of the array

- Which of these are reasons for using pointers?

1. To manipulate parts of an array 2. To refer to keywords, such as for and if 3. To return more than one value from a function 4. To refer to particular programs more conveniently

- If you don’t initialize a static array, what will be the elements set to?

1. 0 2. an undetermined value 3. a floating point number 4. the character constant ‘\0’

[H] State True or False:

-

Address of a floating-point variable is always a whole number.

-

Which of the following is the correct way of declaring a float pointer:

1. float ptr; 2. float *ptr;

3. *float ptr; 4. None of the above

- Add the missing statement for the following program to print 35:

#include <stdio.h> int main() { int j, *ptr; *ptr = 35; printf("%d\n", j); return 0; }

- if int s[5] is a one-dimensional array of integers, which of the following refers to the third element in the array?

1. *(s + 2) 2. *(s + 3) 3. s + 3 4. s + 2

[I] Attempt the following:

-

Write a program to copy the contents of one array into another in the reverse order.

-

If an array arr contains n elements, then write a program to check if arr[0] = arr[n-1], arr[1] = arr[n - 2] and so on.

-

Write a program using pointers to find the smallest number in an array of 25 integers.

-

Write a program which performs the following tasks:

-

Initialize an integer array of 10 elements in main()

-

Pass the entire array to a function modify()

-

In modify() multiply each element of array by 3

-

Return the control to main() and print the new array elements in main()