Asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction is wide spread among different organisms. It is common in members of Protista, Bacteria, Archaea and in multicellular organisms with relatively simpler organisation. The offsprings show “uniparental inheritance” without any genetic variation. The different modes of asexual reproduction seen in animals are fission, budding, fragmentation and regeneration.

Fission is the division of the parent body into two or more identical daughter individuals. Five types of fission are seen in animals. They are binary fission, multiple fission, plasmotomy, strobilation and sporulation.

In binary fission, the parent organism divides into two halves and each half forms a daughter individual. The nucleus divides first amitotically or mitotically (karyokinesis), followed by the division of the cytoplasm (cytokinesis). The resultant offsprings are genetically identical to the parent. Depending on the plane of fission, binary fission is of the following types,

i)Simple irregular binary fission ii) Transverse binary fission iii) Longitudinal binary fission iv) Oblique binary fission

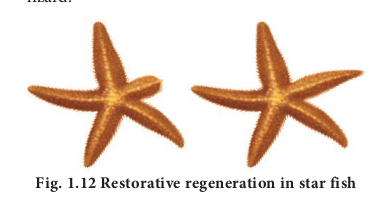

Simple irregular binary fission is seen in irregular shaped organisms like Amoeba (Fig. 1.1), where the plane of division is hard to observe. The contractile vacuoles cease to function and disappear. The nucleoli disintegrate and the nucleus divides mitotically. The cell then constricts in the middle, so the cytoplasm divides and forms two daughter cells.

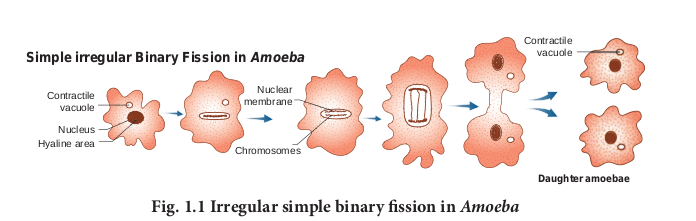

In transverse binary fission, the plane of the division runs along the transverse axis of the individual. e.g. Paramecium and Planaria. In Paramecium (Fig. 1.2) the macronucleus divides by amitosis and the micronucleus divides by mitosis.

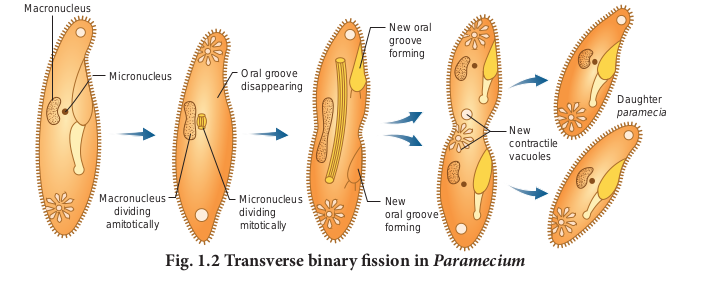

In longitudinal binary fission, the nucleus and the cytoplasm divides in the longitudinal axis of the organism (Fig 1.3). In flagellates, the flagellum is retained usually by one daughter cell. The basal granule is divided into two and the new basal granule forms a flagellum in the other daughter individual. e.g. Vorticella and Euglena.

In oblique binary fission the plane of division is oblique. It is seen in dinoflagellates. e.g. Ceratium.

In multiple fission the parent body divides into many similar daughter cells simultaneously. First, the nucleus divides repeatedly, later the cytoplasm divides into as many parts as that of nuclei. Each cytoplasmic part encircles one daughter nucleus. This results in the formation of many smaller individuals from a single parent organism. If multiple fission produces four or many daughter individuals by equal cell division and the young ones do not separate until the process is complete, then this division is called repeated fission. e.g. Vorticella.

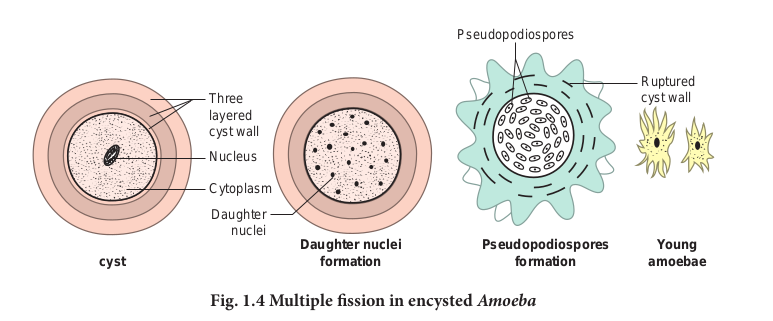

During unfavorable conditions (increase or decrease in temperature, scarcity of food) Amoeba withdraws its pseudopodia and secretes a three-layered, protective, chitinous cyst wall around it and becomes inactive (Fig. 1.4). This phenomenon is called encystment. When conditions become favourable, the encysted Amoeba divides by multiple fission and produces many minute amoebae called pseudopodiospore or amoebulae. The cyst wall absorbs water and breaks off liberating the young pseudopodiospores, each with a fine pseudopodia. They feed and grow rapidly to lead an independent life.

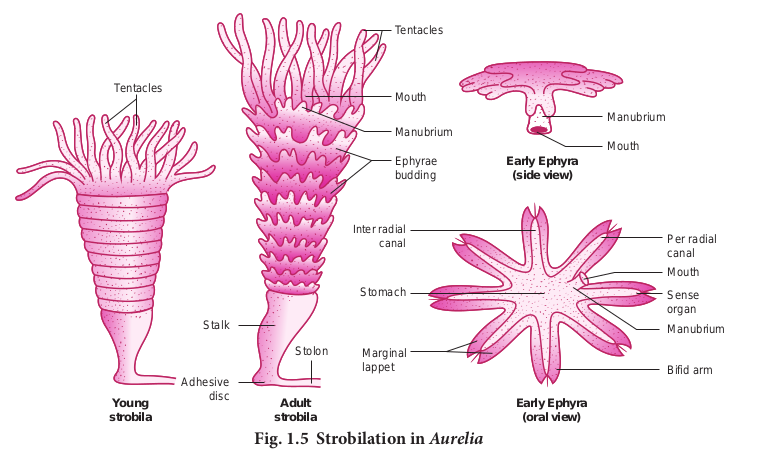

In some metazoan animals, a special type of transverse fission called strobilation occurs

(Fig. 1.5). In the process of strobilation, several transverse fissions occur simultaneously giving rise to a number of individuals which often do not separate immediately from each other e.g. Aurelia. Plasmotomy is the division of multinucleated parent into many multinucleate daughter individuals with the division of nuclei. Nuclear division occurs later to maintain normal number of nuclei. Plasmotomy occurs in Opalina and _Pelomyxa (_Giant Amoeba).

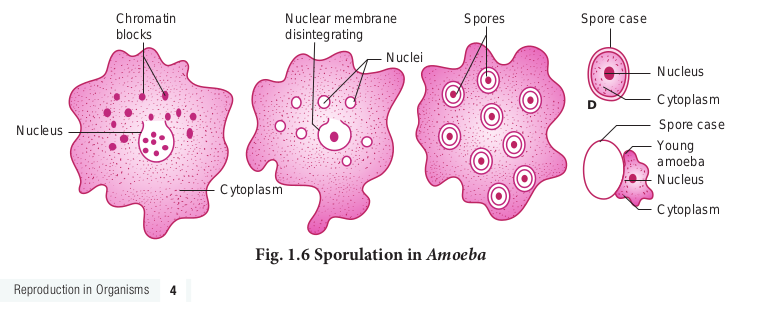

During unfavourable conditions Amoeba multiplies by sporulation without encystment.

Nucleus breaks into several small fragments or chromatin blocks. Each fragment develops a nuclear membrane, becomes surrounded by cytoplasm and develops a spore-case around it (Fig. 1.6). When conditions become favourable, the parent body disintegrates and the spores are liberated, each hatching into a young amoeba.

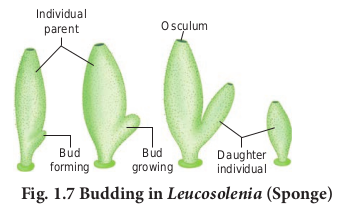

In budding, the parent body produces one or more buds and each bud grows into a young one. The buds separate from the parent to lead a normal life. In sponges, the buds constrict and detach from the parent body and the bud develops into a new sponge (Fig. 1.7).

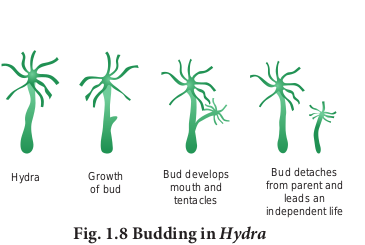

When buds are formed on the outer surface of the parent body, it is known as exogenous budding e.g. Hydra. In Hydra when food is plenty, the ectoderm cells increase and form a small elevation on the body surface (Fig. 1.8). Ectoderm and endoderm are pushed out to form the bud. The bud contains an interior lumen in continuation with parent’s gastro-vascular cavity. The bud enlarges, develops a mouth and a circle of tentacles at its free end. When fully grown, the bud constricts at the base and finally separates from the parent body and leads an independent life.

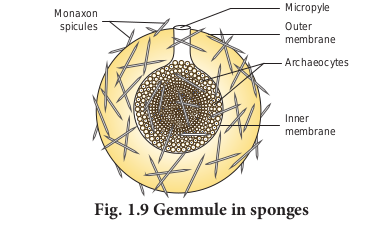

In Noctiluca, hundreds of buds are formed inside the cytoplasm and many remain within the body of the parent. This is called endogenous budding. In freshwater sponges and in some marine sponges a regular and peculiar mode of asexual reproduction occurs by internal buds called gemmules is seen (Fig. 1.9). A completely grown gemmule is a hard ball, consisting of an internal mass of food-laden archaeocytes. During unfavourable conditions, the sponge disintegrates but the gemmule can withstand adverse conditions. When conditions become favourable, the gemmules begin to hatch.

In fragmentation, the parent body breaks into fragments (pieces) and each of the fragment has the potential to develop into a new individual. Fragmentation or pedal laceration occurs in many genera of sea anemones. Lobes are constricted off from the pedal disc and each of the lobe grows mesenteries and tentacles to form a new sea anemone.

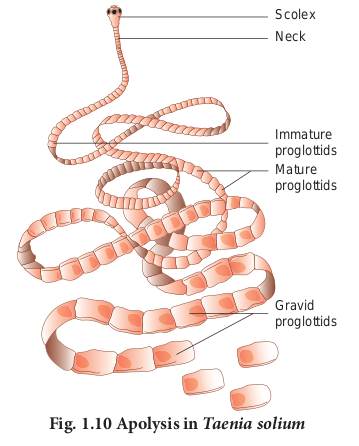

In the tapeworm, Taenia solium, the gravid (ripe) proglottids are the oldest at the posterior end of the strobila (Fig. 1.10). The gravid proglottids are regularly cut off either singly or in groups from the posterior end by a process called apolysis. This is very significant since it helps in transferring the developed embryos from the primary host (man) to find a secondary host (pig).

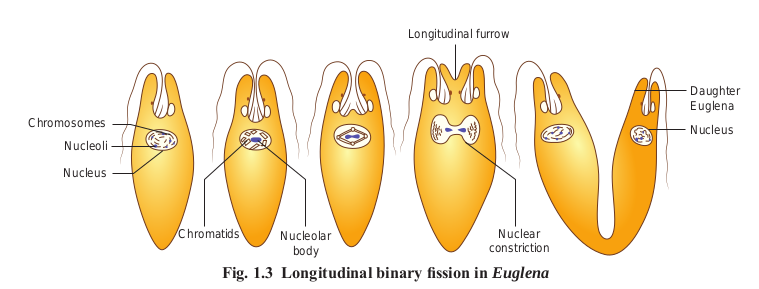

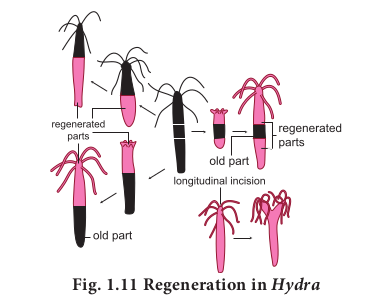

Regen eration is regrowth in the injured region. Regeneration was first studied in Hydra by Abraham Trembley in 1740. Regeneration is of two types, morphallaxis and epimorphosis. In morphallaxis the whole body grows from a small fragment e.g. Hydra and Planaria. When Hydra is accidentally cut into several pieces, each piece can regenerate the lost parts and develop into a whole new individual (Fig. 1.11). The parts usually retain their original polarity, with oral ends, by developing tentacles and aboral ends, by producing basal discs. Epimorphosis (Fig. 1.12) is the replacement of lost body parts. It is of two types, namely reparative and restorative regeneration. In reparative regeneration, only certain damaged tissue can be regenerated, e.g. human beings whereas in restorative regeneration severed body parts can develop. e.g. star fish, tail of wall lizard.