LORENTZ FORCE

When an electric charge (q) is kept at rest in a magnetic field, no force acts on it. At the same time, if the charge moves in the magnetic field, it experiences a force. This force is different from Coulomb force, studied in unit 1. This force is known as magnetic force. It is given by the equation

\(\vec{F} = q \vec{v} \times \vec{B} \quad (3.54)\)In general, if the charge is moving in both the electric and magnetic fields, the total force experienced by the charge is given by

\(\vec{F} = q(\vec{E} + \vec{v} \times \vec{B})\)It is known as Lorentz force.

Force on a moving charge in a magnetic field

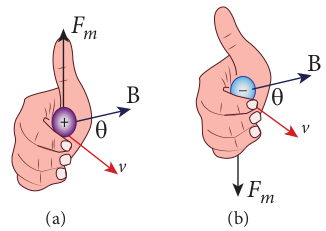

When an electric charge q is moving with velocity \( \vec{v} \) in the magnetic field \( \vec{B} \) , it experiences a force, called magnetic force \( \vec{F}_m \) . After careful experiments, Lorentz deduced the force experienced by a moving charge in the magnetic field:

\(\vec{F}_m = q (\vec{v} \times \vec{B}) \quad (3.55)\)In magnitude, \( F_m = qv\sin(\theta) \) (3.56)

The equations (3.55) and (3.56) imply:

- \( \vec{F}_m \) is directly proportional to the magnetic field \( \vec{B}\)

- \( \vec{F}_m \) is directly proportional to the velocity \( \vec{v} \) of the moving charge

- \( \vec{F}_m \) is directly proportional to the sine of the angle between the velocity and magnetic field

- \( \vec{F}_m \) is directly proportional to the magnitude of the charge q

- The direction of \( \vec{F}_m \) is always perpendicular to \( \vec{v} \) and \( \vec{B} \) as \( \vec{F}_m \) is the cross product of \( \vec{v} \) and \( \vec{B} \) .

- The direction of \( \vec{F}_m \) on a negative charge is opposite to the direction of \( \vec{F}_m \) on a positive charge provided other factors are identical, as shown in Figure 3.44 (b).

- If the velocity \( \vec{v} \) of the charge q is along the magnetic field \( \vec{B} \) , then \( \vec{F}_m \) is zero.

Definition of tesla: The strength of the magnetic field is one tesla if a unit charge moving in it with unit velocity experiences unit force.

\( 1 \, \text{T} = 1 \, \text{Ns/C m} = 1 \, \text{N/A m} = 1 \, \text{N A}^{-1} m^{-1}\)EXAMPLE 3.17

A particle of charge q moves with velocity \( \vec{v} \) along the positive y-direction in a magnetic field \( \vec{B} \) . Compute the Lorentz force experienced by the particle: (a) when the magnetic field is along the positive y-direction, (b) when the magnetic field points in the positive z-direction, (c) when the magnetic field is in the zy-plane and making an angle \( \theta \) with the velocity of the particle. Mark the direction of the magnetic force in each case.

Solution

Velocity of the particle is \( \vec{v} = \hat{j} \) .

(a) Magnetic field is along positive y-direction, which implies \( \vec{B} = \hat{j}\) . From Lorentz force, \( \vec{F}_m = q (\vec{v} \times \vec{B}) = \vec{0} \) . So, no force acts on the particle when it moves along the direction of the magnetic field.

(b) Since the magnetic field points in positive \( z \) -direction, which implies \( \vec{B} = \hat{k} \) . From Lorentz force, \( \vec{F}_m = q (\vec{v} \times \vec{B}) = qv \hat{i} \) . Therefore, the magnitude of the Lorentz force is \( qvB \) and the direction is along the positive \( x \) -direction.

(c) Magnetic field is in the zy-plane and making an angle \( \theta \) with the velocity of the particle, which implies \( \vec{B} = \hat{j}\cos(\theta) + \hat{k}\sin(\theta) \) . From Lorentz force, \( \vec{F}_m = q (\vec{v} \times \vec{B}) = qvB\sin(\theta) \hat{i} \) . Therefore, the magnitude of the Lorentz force is \( qvB\sin(\theta) \) and the direction is along the positive \( x \) -direction.

EXAMPLE 3.18

Compute the work done and power delivered by the Lorentz force on the particle of charge \( q \) moving with velocity \( \vec{v} \) . Calculate the angle between the Lorentz force and velocity of the charged particle and also interpret the result.

Solution

For a charged particle moving in a magnetic field, \( \vec{F}_m = q (\vec{v} \times \vec{B}) \) .

The work done by the magnetic field is \( W = \int \vec{F}_m \cdot d\vec{r} \) , which is zero since \( \vec{F}_m \) and \( d\vec{r} \) are perpendicular to each other.

\( \frac{dW}{dt} = \vec{F}_m \cdot \vec{v} = 0\)Since \( \vec{F}_m \) and \( \vec{v} \) are perpendicular to each other, the angle between them is \( 90^\circ \) . Thus, the Lorentz force changes the direction of the velocity but not the magnitude of the velocity. Hence, the Lorentz force does no work and also does not alter the kinetic energy of the particle.

Motion of a charged particle in a uniform magnetic field

Consider a charged particle of charge ( q ) having mass ( m ) entering into a region of uniform magnetic field ( \mathbf{B} ) with velocity ( \mathbf{v} ) such that velocity is perpendicular to the magnetic field. As soon as the particle enters into the field, Lorentz force acts on it in a direction perpendicular to both magnetic field ( \mathbf{B} ) and velocity ( \mathbf{v} ). As a result, the charged particle moves in a circular orbit as shown in Figure 3.45. The Lorentz force on the charged particle is given by

\( \mathbf{F} = q \mathbf{B} \times \mathbf{v}\)Since Lorentz force alone acts on the particle, the magnitude of the net force on the particle is

\( F = \frac{qBv}{m}\)This Lorentz force acts as centripetal force for the particle causing it to execute circular motion. Therefore,

\( \frac{qvB}{m} = \frac{v^2}{r}\)The radius of the circular path is

\( r = \frac{mv}{qB} \quad \text{(3.57)}\)where ( p = mv ) is the magnitude of the linear momentum of the particle. Let ( T ) be the time taken by the particle to finish one complete circular motion, then

\( T = \frac{2\pi}{v}\)Hence substituting (3.57) in (3.58), we get

\( T = \frac{m}{qB} \frac{1}{2\pi} \quad \text{(3.59)}\)Equation (3.59) is called the cyclotron period. The reciprocal of time period is the frequency ( f ), which is

\( f = \frac{1}{T} = \frac{qB}{2\pi m} \quad \text{(3.60)}\)In terms of angular frequency ( \omega ),

\( \omega = \frac{\pi}{2} \frac{q}{m} B \quad \text{(3.61)}\)Equations (3.60) and (3.61) are called as cyclotron frequency or gyro-frequency.

From equations (3.59), (3.60), and (3.61), we infer that time period and frequency depend only on charge-to-mass ratio (specific charge) but not on velocity or the radius of the circular path.

If a charged particle moves in a region of uniform magnetic field such that its velocity is not perpendicular to the magnetic field, then the velocity of the particle is split up into two components; one component is parallel to the field while the other component perpendicular to the field. The component of velocity parallel to the field remains unchanged, and the component perpendicular to the field keeps changing due to Lorentz force. Hence the path of the particle is not a circle; it is a helix around the field lines.

For example, the helical path of an electron when it moves in a magnetic field is shown in Figure 3.47. Inside the particle detector called a cloud chamber, the path is made visible by the condensation of water droplets.

EXAMPLE 3.19

An electron moving perpendicular to a uniform magnetic field 0.500 T undergoes circular motion of radius 2.50 mm. What is the speed of the electron?

Solution

Charge of an electron ( q = -1.60 \times 10^{-19} ) C ⇒ ( q = -e )

Magnitude of magnetic field ( B = 0.500 ) T

Mass of the electron, ( m = 9.11 \times 10^{-31} ) kg

Radius of the orbit, ( r = 2.50 ) mm = ( 2.50 \times 10^{-3} ) m

Speed of the electron,

\( v = \frac{q rB}{m} = \frac{1.60 \times 10^{-19} \times 2.50 \times 10^{-3} \times 0.500}{9.11 \times 10^{-31}}\) \( v = 2.195 \times 10^8 \, \text{m/s}\)EXAMPLE 3.20

A proton moves in a uniform magnetic field of strength 0.500 T magnetic field is directed along the x-axis. At initial time, ( t = 0 ), the proton has velocity ( \mathbf{v} = (1.95 \times 10^5 \mathbf{i} + 2.00 \times 10^5 \mathbf{j} + 5.00 \times 10^5 \mathbf{k}) ) m/s. Find

(a) At initial time, what is the acceleration of the proton.

(b) Is the path circular or helical? If helical, calculate the radius of helical trajectory and also calculate the pitch of the helix (Note: Pitch of the helix is

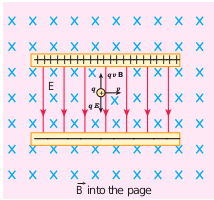

Motion of a charged particle under crossed electric and magnetic field (velocity selector)

For a positive charge, the electric force on the charge acts in the downward direction, whereas the Lorentz force acts upwards. When these two forces balance each other, then

\( qE = qBv \) \( v = \frac{E}{B} \)(3.62)

This principle is used in the Bainbridge mass spectrograph to separate isotopes. This concept is explained in Example (3.21).

Schematic diagram of Bainbridge mass spectrometer

\( m_2 > m_1 \) \( 2r \) \( m_2 \) \( B \) \( S2 \) \( S1 \) \( m_1 \)Magnetic field perpendicular to the diagram and into the plane

Beam of positive ions

Vacuum chamber

Note: \( \Delta d = d_2 - d_1 \) \( t_{235} = \frac{97.6 \times 10^{-2}}{5.76 \times 10^{5}} \) \( t_{238} = \frac{98.8 \times 10^{-2}}{5.88 \times 10^{5}} \)

This means, for a given magnitude of \( \vec{E}\) -field and \( \vec{B}\) -field, the forces act only on the particle moving with a particular speed \( v_{\text{0}} = \frac{E}{B}\) . This speed is independent of mass and charge.

By proper choice of electric and magnetic fields, the particle with a particular speed can be selected. Such an arrangement of fields is called a velocity selector.

EXAMPLE 3.22

Let \( E \) be the electric field of magnitude \( 6.0 \times 10^6 \, \text{N C}^{-1} \) and \( B \) be the magnetic field magnitude \( 0.83 \, \text{T} \) . Suppose an electron is accelerated with a potential of \( 200 \, \text{V} \) , will it show zero deflection? If not, at what potential will it show zero deflection.

Solution:

Electric field, \( E = 6.0 \times 10^6 \, \text{N C}^{-1} \) and magnetic field, \( B = 0.83 \, \text{T} \) .

\( v_0 = \frac{E}{B} = \frac{6.0 \times 10^6}{0.83} \, \text{m/s} \)When an electron goes with this velocity, it shows null deflection. Since the accelerating potential is \( 200 \, \text{V} \) , the electron acquires kinetic energy because of this accelerating potential. Hence,

\( \frac{1}{2} m_e v_{200}^2 = eV \)Since the mass of the electron, \( m_e = 9.1 \times 10^{-31} \, \text{kg} \) and charge of an electron, \( e = -1.6 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{C} \) , the velocity acquired by the electron due to the accelerating potential of \( 200 \, \text{V} \) is

\( v_{200} = \sqrt{\frac{2 \cdot 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \cdot 200}{9.1 \times 10^{-31}}} \, \text{m/s} \)Since the speed \( v_{200} > v_0 \) , the electron is deflected towards the direction of the Lorentz force. So, in order to have null deflection, the potential we have to supply is

\( V = \frac{1}{2} m_e v_{200}^2 = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 9.1 \times 10^{-31} \cdot (148 \times 10^3)^2 \) \( V = 65 \, \text{V} \)

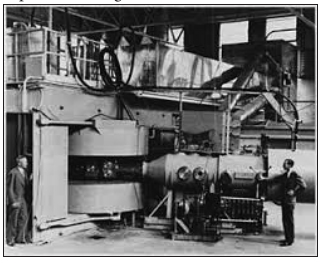

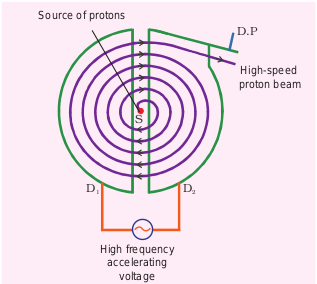

Cyclotron

Cyclotron (Figure 3.49) is a device used to accelerate charged particles to gain large kinetic energy. It is also called a high energy accelerator and was invented by Lawrence and Livingston in 1934.

Principle

When a charged particle moves perpendicular to the magnetic field, it experiences magnetic Lorentz force.

Construction

The schematic diagram of a cyclotron is shown in Figure 3.50. The particles move between two semi-circular metal containers called Dees (hollow D-shaped objects). Dees are enclosed in an evacuated chamber and are kept in a region with a uniform magnetic field controlled by an electromagnet. The direction of the magnetic field is normal to the plane of the Dees. The two Dees are kept separated with a gap, and the source (S) (which ejects the particle to be accelerated) is placed at the center in the gap between the Dees. Dees are connected to a high-frequency alternating potential difference.

Working

Let us assume that the ion ejected from the source (S) is positively charged. As soon as the ion is ejected, it is accelerated towards a Dee (say, Dee – 1) which has a negative potential at that time. Since the magnetic field is normal to the plane of the Dees, the ion moves in a circular path. After one semi-circular path inside Dee-1, the ion reaches the gap between Dees. At this time, the polarities of the Dees are reversed, so the ion is now accelerated towards Dee-2 with greater velocity. For this circular motion, the centripetal force on the charged particle (q) is provided by the Lorentz force.

\( \frac{m r v^2}{r} = q B v\) \( v \propto \frac{r}{\sqrt{r}}\)From the equation (3.63), the increase in velocity increases the radius of the circular path. This process continues, and hence the particle moves in a spiral path of increasing radius. Once it reaches near the edge, it is taken out with the help of a deflector plate and allowed to hit the target (T).

The important condition in cyclotron operation is that the frequency (f) at which the positive ion circulates in the magnetic field must be equal to the constant frequency of the electrical oscillator (f_{\text{osc}}). This is called the resonance condition.

\( f = \frac{q B}{2\pi m}\)The time period of oscillation is

\( T = \frac{2\pi m}{q B}\)The kinetic energy of the charged particle is

\( KE = \frac{1}{2} m q B r^2\)Limitations of cyclotron (a) The speed of the ion is limited. (b) Electrons cannot be accelerated. (c) Uncharged particles cannot be accelerated.

Note

EXAMPLE 3.23

Suppose a cyclotron is operated to accelerate protons with a magnetic field of strength 1 T. Calculate the frequency in which the electric field between two Dees could be reversed.

Solution

Magnetic field (B = 1 , \text{T}), mass of the proton (m_p = 1.67 \times 10^{-27} , \text{kg}), charge of the proton (q = 1.6 \times 10^{-19} , \text{C}).

\( f = \frac{q B}{2\pi m_p} = \frac{1.6 \times 10^{-19} \times 1}{2 \times \pi \times 1.67 \times 10^{-27}} \, \text{Hz}\) \( f \approx 3 \, \text{MHz}\)Force on a current carrying conductor placed in a magnetic field

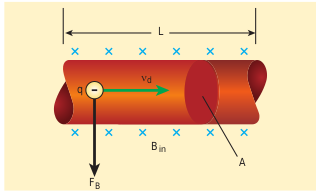

When a current carrying conductor is placed in a magnetic field, the force experienced by the conductor is equal to the sum of Lorentz forces on the individual charge carriers in the conductor. Consider a small segment of conductor of length (dl), with cross-sectional area (A) and current (I) as shown in Figure 3.51. The free electrons drift opposite to the direction of the current. So the relation between current (I) and the magnitude of drift velocity (v_d) (Refer Unit 2) is

\( I = neAv_d \, (3.65)\)If the conductor is kept in a magnetic field (\vec{B}), then the average force experienced by the charge (electron) in the conductor is

\( \vec{F_e} = -e \vec{v_d} \times \vec{B}\)If (n) is the number of free electrons present in unit volume, then

\( n = \frac{N}{V}\)where (N) is the number of free electrons in the small element of volume (V = Adl).

Hence Lorentz force on the elementary section of length (dl) is the product of the number of the electrons ((N = nAdl)) and the force acting on each electron.

\( \vec{F} = -e n Adl \vec{v_d} \times \vec{B}\)The current element in the conductor is (Idl = enAdl v_d). Therefore the force on the small elemental section of the current-carrying conductor is

\( d\vec{F} = I \, dl \, \vec{B} \, (3.66)\)

(-)

EXAMPLE 3.23

Suppose a cyclotron is operated to accelerate protons with a magnetic field of strength (1 , \text{T}). Calculate the frequency in which the electric field between two Dees could be reversed.

Solution

Magnetic field (B = 1 , \text{T}), mass of the proton (m_p = 1.67 \times 10^{-27} , \text{kg}), charge of the proton (q = 1.6 \times 10^{-19} , \text{C}).

\( f = \frac{q B}{2\pi m_p} = \frac{1.6 \times 10^{-19} \times 1}{2 \times \pi \times 1.67 \times 10^{-27}} \, \text{Hz}\) \( f \approx 3 \, \text{MHz}\)Thus, the force on a straight current-carrying conductor of length (l) placed in a uniform magnetic field is

\( \vec{F} = I \, \vec{l} \times \vec{B} \, (3.67)\)In magnitude,

\( F = BIl \sin \theta_{\text{total}}\)(a) If the conductor is placed along the direction of the magnetic field, then the angle ( \theta ) is (0^\circ ). Hence, the force experienced by the conductor is zero.

(b) If the conductor is placed perpendicular to the magnetic field, then the angle ( \theta = 90^\circ ). Hence, the force experienced by the conductor is maximum, which is ( F_{\text{total}} = BIl ).

Fleming’s left hand rule When a current-carrying conductor is placed in a magnetic field, the direction of the force experienced by it is given by Fleming’s Left Hand Rule (FLHR) as shown in Figure 3.52.

Figure 3.52 Fleming’s Left Hand Rule (FLHR)

\( \text{Force} \quad \quad \text{Magnet}\) \( \text{Current}\)Stretch out forefinger, the middle finger, and the thumb of the left hand such that they are in three mutually perpendicular directions. If the forefinger points in the direction of the magnetic field, the middle finger in the direction of the electric current, then the thumb will point in the direction of the force experienced by the conductor.

EXAMPLE 3.24

A metallic rod of linear density is (0.25 , \text{kg m}^{-1}) is lying horizontally on a smooth inclined plane which makes an angle of (45^\circ) with the horizontal. The rod is not allowed to slide down by flowing a current through it when a magnetic field of strength (0.25 , \text{T}) is acting on it in the vertical direction. Calculate the electric current flowing in the rod to keep it stationary.

\( \vec{mg} \sin 45^\circ\) \( \vec{B}\) \( 45^\circ\) \( \vec{I}\) \( \vec{B}_{\text{in}}\) \( \vec{T}\)Solution

The linear density of the rod, i.e., mass per unit length of the rod is (0.25 , \text{kg m}^{-1})

\( \Rightarrow \lambda = \frac{m}{l} = 0.25 \, \text{kg m}^{-1}\)Let (I) be the current flowing in the metallic rod. The direction of the electric current is into the plane of the paper. The direction of magnetic force (\vec{IBl}) is given by Fleming’s left-hand rule.

\( \vec{mg} \sin 45^\circ\) \( \vec{B}\) \( 45^\circ\) \( 45^\circ\) \( \vec{BI}_l \cos 45^\circ\) \( \vec{BI}_l\) \( \vec{I}\) \( \vec{B}_{\text{in}}\)For equilibrium of the rod,

\( \vec{mg} \, \vec{IBl} \sin 45^\circ \cos 45^\circ = 0\) \( \Rightarrow I \, B \, m \, l \, g \, \tan 45^\circ = \frac{0.25 \times 1 \times 9.8}{2} \, \text{A}\) \( \Rightarrow I = \frac{0.25 \times 1 \times 9.8}{2} \, \text{A}\) \( \Rightarrow I = 0.25 \, \text{A}\)So, we need to supply a current of 0.25 A to keep the metallic rod stationary.

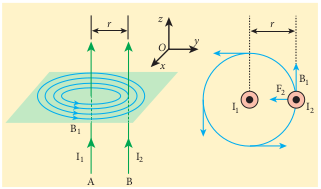

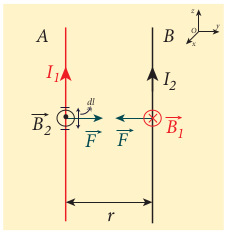

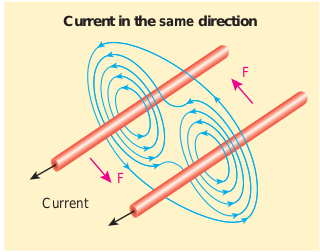

Force between two long parallel current carrying conductors

Let two long straight parallel current carrying conductors separated by a distance (r) be kept in an air medium as shown in Figure 3.53. Let (I_1) and (I_2) be the electric currents passing through the conductors A and B in the same direction (i.e., along (z)-direction) respectively. The net magnetic field at a distance (r) due to current (I_1) in conductor A is

\( \vec{B_1} = \frac{\mu I_1}{2\pi r} \hat{i}\)

From the thumb rule, the direction of the magnetic field is perpendicular to the plane of the paper and inwards (arrow into the page (\otimes)), i.e., along the negative (\hat{i}) direction.

Let us consider a small elemental length (dl) in conductor B at which the magnetic field (\vec{B_1}) is present. From equation 3.66, Lorentz force on the element (dl) of conductor B is

\( d\vec{F} = I dl \vec{B_1} = I dl \frac{\mu I_1}{2\pi r} \hat{j}\)Therefore the force on (dl) of the wire B is directed towards the conductor A. So the element of length (dl) in B is attracted towards the conductor A. Hence the force per unit length of the conductor B due to current in the conductor A is

\( \vec{F_l} = -I_1I_2\frac{\mu}{2\pi r} \hat{j}\)Similarly, the net magnetic induction due to current (I_2) (in conductor B) at a distance (r) in the elemental length (dl) of conductor A is

\( \vec{B_2} = \frac{\mu I_2}{2\pi r} \hat{i}\)From the thumb rule, the direction of the magnetic field is perpendicular to the plane of the paper and outwards (arrow out of the page (\epsilon)), i.e., along the positive (\hat{i}) direction. Hence, the magnetic force acting on element (dl) of the conductor A is

\( d\vec{F} = I dl \vec{B_2} = I dl \frac{\mu I_2}{2\pi r} \hat{j}\)Therefore the force on (dl) of conductor A is directed towards the conductor B. So the length (dl) is attracted towards the conductor B as shown in Figure (3.54).

The force acting per unit length of the conductor A due to the current in conductor B is

\( \vec{F_l} = I_1I_2\frac{\mu}{2\pi r} \hat{j}\)Thus, the force between two parallel current carrying conductors is attractive if they carry current in the same direction (Figure 3.55).

Current in the same direction

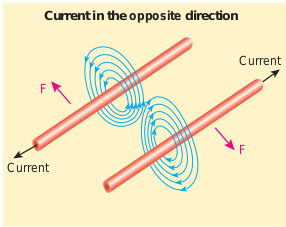

The force between two parallel current carrying conductors is repulsive if they carry current in opposite directions (Figure 3.56).

Definition of ampere: One ampere is defined as that constant current which, when passed through each of the two infinitely long parallel straight conductors kept side by side parallelly at a distance of one meter apart in air or vacuum, causes each conductor to experience a force of (2 \times 10^{-7}) newton per meter length of conductor.