DIFFERENTIAL CALCULUS

The Concept of a function

- Any physical quantity is represented by a “function” in mathematics. Take the example of temperature \(\mathrm{T}\) . We know that the temperature of the surroundings is changing throughout the day. It increases till noon and decreases in the evening. At any time " \(\mathrm{t}\) " the temperature \(\mathrm{T}\) has a unique value. Mathematically this variation can be represented by the notation ’ \(\mathrm{T}(\mathrm{t})\) ’ and it should be called “temperature as a function of time”. It implies that if the value of ’ \(t\) ’ is given, then the function " \(\mathrm{T}(\mathrm{t})\) " will give the value of the temperature at that time ’ \(t\) ‘. Similarly, the position of a bus in motion along the \(\mathrm{x}\) direction can be represented by \(x(t)\) and this is called ’ \(x\) ’ as a function of time’. Here ’ \(x\) ’ denotes the \(\mathrm{x}\) coordinate.

Example

Consider a function \(f(x)=x^{2}\) . Sometimes it is also represented as \(y=x^{2}\) . Here \(y\) is called the dependent variable and \(\mathrm{x}\) is called independent variable. It means as \(x\) changes, \(\mathrm{y}\) also changes. Once a physical quantity is represented by a function, one can study the variation of the function over time or over the independent variable on which the quantity depends. Calculus is the branch of mathematics used to analyse the change of any quantity.

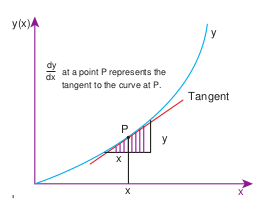

If a function is represented by \(y=f(x)\) , then \(d y / d x\) represents the derivative of \(y\) with respect to \(x\) . Mathematically this represents the variation of \(y\) with respect to change in \(\mathrm{x}\) , for various continuous values of \(\mathrm{x}\) .

Mathematically the derivative \(\mathrm{dy} / \mathrm{dx}\) is defined as follows

\(\begin{aligned} \frac{d y}{d x} & =\lim _{\Delta x \rightarrow 0} \frac{y(x+\Delta x)-y(x)}{\Delta x} \\ & =\lim _{\Delta x \rightarrow 0} \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} \end{aligned}\)\(\frac{d y}{d x}\) represents the limit that the quantity \(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\) attains, as \(\Delta x\) tends to zero. Graphically this is represented as shown in Figure 2.28.

Figure 2.28 Derivative of a function

EXAMPLE 2.18

Consider the function \(y=x^{2}\) . Calculate the derivative \(\frac{d y}{d x}\) using the concept of limit, at the point \(x=2\) .

Solution

Let us take two points given by

\(\mathrm{x}_{1}=2 \text { and } \mathrm{x}_{2}=3 \text {, then } \mathrm{y}_{1}=4 \text { and } \mathrm{y}_{2}=9\)Here \(\Delta x=1\) and \(\Delta y=5\)

Then

\(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}=\frac{9-4}{3-2}=5\)If we take \(\mathrm{x}_{1}=2\) and \(\mathrm{x}_{2}=2.5\) , then \(\mathrm{y}_{1}=4\) and \(\mathrm{y}_{2}=(2.5)^{2}=6.25\)

\(\text { Here } \Delta x=0.5=\frac{1}{2} \text { and } \Delta y=2.25\)Then

\(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}=\frac{6.25-4}{0.5}=4.5\)If we take \(\mathrm{x}_{1}=2\) and \(\mathrm{x}_{2}=2.25\) , then \(\mathrm{y}_{1}=4\) and \(\mathrm{y}_{2}=5.0625\)

\(\text { Here } \Delta x=0.25=\frac{1}{4}, \Delta y=1.0625\) \(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}=\frac{5.0625-4}{0.25}=\frac{(5.0625-4)}{\frac{1}{4}}\) \(=4(5.0625-4)=4.25\)If we take \(\mathrm{x}_{1}=2\) and \(\mathrm{x}_{2}=2.1\) , then \(\mathrm{y}_{1}=4\) and \(\mathrm{y}_{2}=4.41\)

\(\begin{gathered} \text { Here } \Delta x=0.1=\frac{1}{10} \text { and } \\ \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}=\frac{(4.41-4)}{\frac{1}{10}}=10(4.41-4)=4.1 \end{gathered}\)These results are tabulated as shown below:

| \(\mathrm{x}_{1}\) | \(\mathrm{x}_{2}\) | \(\Delta x\) | \(\mathrm{y}_{1}\) | \(\mathrm{y}_{2}\) | \(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2.25 | 0.25 | 4 | 5.0625 | 4.25 |

| 2 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 4 | 4.41 | 4.1 |

| 2 | 2.01 | 0.01 | 4 | 4.0401 | 4.01 |

| 2 | 2.001 | 0.001 | 4 | 4.004001 | 4.001 |

| 2 | 2.0001 | 0.0001 | 4 | 4.00040001 | 4.0001 |

From the above table, the following inferences can be made.

- As \(\Delta x\) tends to zero, \(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\) approaches the limit given by the number 4 .

- At a point \(\mathrm{x}=2\) , the derivative \(\frac{d y}{d x}=4\) .

- It should also be mentioned here that \(\Delta x \rightarrow 0\) does not mean that \(\Delta x=0\) . This is because, if we substitute \(\Delta x=0\) , \(\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\) becomes indeterminate.

In general, we can obtain the derivative of the function \(y=x^{2}\) , as follows:

\(\begin{aligned} \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} & =\frac{(x+\Delta x)^{2}-x^{2}}{\Delta x}=\frac{x^{2}+2 x \Delta x+\Delta x^{2}-x^{2}}{\Delta x} \\ & =\frac{2 x \Delta x+\Delta x^{2}}{\Delta x}=2 x+\Delta x \\ & \frac{d y}{d x}=\lim _{\Delta x \rightarrow 0} 2 x+\Delta x=2 x \end{aligned}\)The table below shows the derivatives of some common functions used in physics

| Function | Derivative |

|---|---|

| \(y=x\) | \(d y / d x=1\) |

| \(y=x^{2}\) | \(d y / d x=2 x\) |

| \(y=x^{3}\) | \(d y / d x=3 x^{2}\) |

| \(y=x^{n}\) | \(d y / d x=n x^{n-1}\) |

| \(y=\sin x\) | \(d y / d x=\cos x\) |

| \(y=\cos x\) | \(d y / d x=-\sin x\) |

| \(y=\operatorname{constant}<span> \( | \) </span> d y / d x=0\) | |

| \(y=A B\) | \(\frac{d y}{d x}=A\left(\frac{d B}{d x}\right)+\left(\frac{d A}{d x}\right) B\) |

In physics, velocity, speed and acceleration are all derivatives with respect to time ’ \(\mathrm{t}\) ‘. This will be dealt with in the next section.

EXAMPLE 2.19

Find the derivative with respect to \(t\) , of the function \(\mathrm{x}=\mathrm{A}_{0}+\mathrm{A}_{1} \mathrm{t}+\mathrm{A}_{2} \mathrm{t}^{2}\) where \(\mathrm{A}_{0}, \mathrm{~A}_{1}\) and \(\mathrm{A}_{2}\) are constants.

Solution

Note that here the independent variable is ’ \(\mathfrak{t}\) ’ and the dependent variable is ’ \(\mathrm{x}\) '

The required derivative is \(\mathrm{dx} / \mathrm{dt}=0+\) \(\mathrm{A}_{1}+2 \mathrm{~A}_{2} \mathrm{t}\)

The second derivative is \(\mathrm{d}^{2} \mathrm{x} / \mathrm{dt}^{2}=2 \mathrm{~A}_{2}\)