Application Architectures

To handle their complexity, large applications are often broken into several layers:

• The presentation or user interface layer, which deals with user interaction. A single application may have several different versions of this layer, corre- sponding to distinct kinds of interfaces such as Web browsers, and user interfaces of mobile phones, which have much smaller screens.

In many implementations, the presentation/user-interface layer is it- self conceptually broken up into layers, based on the model-view-controller (MVC) architecture. The model corresponds to the business-logic layer, de- scribed below. The view defines the presentation of data; a single underlying model can have different views depending on the specific software/device used to access the application. The controller receives events (user actions), executes actions on the model, and returns a view to the user. The MVC ar- chitecture is used in a number of Web application frameworks, which are discussed later in Section 9.5.2.

• The business-logic layer, which provides a high-level view of data and ac- tions on data. We discuss the business-logic layer in more detail in Sec- tion 9.4.1.

• The data access layer, which provides the interface between the business-logic layer and the underlying database. Many applications use an object-oriented language to code the business-logic layer, and use an object-oriented model of data, while the underlying database is a relational database. In such cases, the data-access layer also provides the mapping from the object-oriented data model used by the business logic to the relational model supported by the database. We discuss such mappings in more detail in Section 9.4.2.

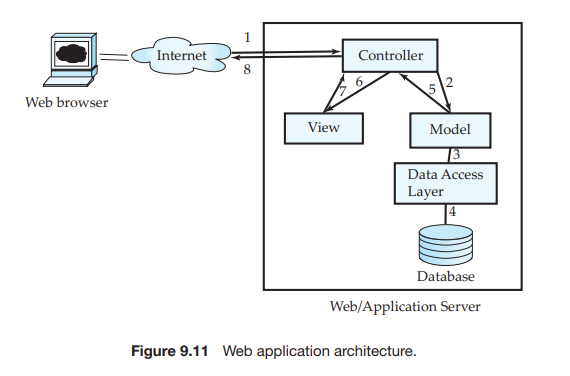

Figure 9.11 shows the above layers, along with a sequence of steps taken to process a request from the Web browser. The labels on the arrows in the figure indicate the order of the steps. When the request is received by the application server, the controller sends a request to the model. The model processes the

request, using business logic, which may involve updating objects that are part of the model, followed by creating a result object. The model in turn uses the data- access layer to update or retrieve information from a database. The result object created by the model is sent to the view module, which creates an HTML view of the result, to be displayed on the Web browser. The view may be tailored based on the characteristics of the device used to view the result, for example whether it is a computer monitor with a large screen, or a small screen on a phone.

The Business-Logic Layer

The business-logic layer of an application for managing a university may provide abstractions of entities such as students, instructors, courses, sections, etc., and actions such as admitting a student to the university, enrolling a student in a course, and so on. The code implementing these actions ensures that business rules are satisfied; for example the code would ensure that a student can enroll for a course only if she has already completed course prerequisites, and has paid her tuition fees.

In addition, the business logic includes workflows, which describe how a particular task that involves multiple participants is handled. For example, if a candidate applies to the university, there is a workflow that defines who should see and approve the application first, and if approved in the first step, who should see the application next, and so on until either an offer is made to the student, or a rejection note is sent out. Workflow management also needs to deal with error situations; for example, if a deadline for approval/rejection is not met, a supervisor may need to be informed so she can intervene and ensure the application is processed. Workflows are discussed in more detail in Section 26.2.

The Data-Access Layer and Object-Relational Mapping

In the simplest scenario, where the business-logic layer uses the same data model as the database, the data-access layer simply hides the details of interfacing with the database. However, when the business-logic layer is written using an object- oriented programming language, it is natural to model data as objects, with methods invoked on objects.

In early implementations, programmers had to write code for creating objects by fetching data from the database, and for storing updated objects back in the database. However, such manual conversions between data models is cumber- some and error prone. One approach to handling this problem was to develop a database system that natively stores objects, and relationships between objects. Such databases, called object-oriented databases, are discussed in more detail in Chapter 22. However, object-oriented databases did not achieve commercial success for a variety of technical and commercial reasons.

An alternative approach is to use traditional relational databases to store data, but to automate the mapping of data in relations to in-memory objects, which are created on demand (since memory is usually not sufficient to store all data in the database), as well as the reverse mapping to store updated objects back as relations in the database.

Several systems have been developed to implement such object-relational mappings. The Hibernate system is widely used for mapping from Java objects to relations. In Hibernate, the mapping from each Java class to one or more relations is specified in a mapping file. The mapping file can specify, for example, that a Java class called Student is mapped to the relation student, with the Java attribute ID mapped to the attribute student.ID, and so on. Information about the database, such as the host on which it is running, and user name and password for connecting to the database, etc., are specified in a properties file. The program has to open a session, which sets up the connection to the database. Once the session is set up, a Student object stud created in Java can be stored in the database by invoking session.save(stud). The Hibernate code generates the SQL commands required to store corresponding data in the student relation.

A list of objects can be retrieved from the database by executing a query written in the Hibernate query language; this is similar to executing a query us- ing JDBC, which returns a ResultSet containing a set of tuples. Alternatively, a single object can be retrieved by providing its primary key. The retrieved objects can be updated in memory; when the transaction on the ongoing Hibernate ses- sion is committed, Hibernate automatically saves the updated objects by making corresponding updates on relations in the database.

While entities in an E-R model naturally correspond to objects in an object- oriented language such as Java, relationships often do not. Hibernate supports the ability to map such relationships as sets associated with objects. For example, the takes relationship between student and section can be modeled by associating a set of _section_s with each student, and a set of _student_s with each section. Once the appropriate mapping is specified, Hibernate populates these sets automatically from the database relation takes, and updates to the sets are reflected back to the database relation on commit.

HIBERNATE EXAMPLE

As an example of the use of Hibernate, we create a Java class corresponding to the student relation as follows.

public class Student {

String ID;

String name;

String department;

int tot cred;

Student(String id, String name, String dept, int totcreds); // constructor

}

To be precise, the class attributes should be declared as private, and getter/setter methods should be provided to access the attributes, but we omit these details.

The mapping of the class attributes of Student to attributes of the relation student is specified in a mapping file, in an XML format. Again, we omit details.

The following code snippet then creates a Student object and saves it to the database.

Session session = getSessionFactory().openSession();

Transaction txn = session.beginTransaction();

Student stud = new Student("12328", "John Smith", "Comp. Sci.", 0);

session.save(stud);

txn.commit();

session.close();

Hibernate automatically generates the required SQL insert statement to create a student tuple in the database.

To retrieve students, we can use the following code snippet

Session session = getSessionFactory().openSession();

Transaction txn = session.beginTransaction();

List students =

session.find("from Student as s order by s.ID asc");

for ( Iterator iter = students.iterator(); iter.hasNext(); ) {

Student stud = (Student) iter.next();

.. print out the Student information ..

}

txn.commit();

session.close();

The above code snippet uses a query in Hibernate’s HQL query language. The HQL query is automatically translated to SQL by Hibernate and executed, and the results are converted into a list of Student objects. The for loop iterates over the objects in this list and prints them out.

The above features help to provide the programmer a high-level model of data without bothering about the details of the relational storage. However, Hibernate, like other object-relational mapping systems, also allows programmers direct SQL access to the underlying relations. Such direct access is particularly important for writing complex queries used for report generation.

Microsoft has developed a data model called the Entity Data Model, which can be viewed as a variant of the entity-relationship model, and an associated framework called the ADO.NET Entity Framework, which can map data between the Entity Data Model and a relational database. The framework also provides an SQL-like query language called Entity SQL, which operates directly on the Entity Data Model.

Web Services

In the past, most Web applications used only data available at the application server and its associated database. In recent years, a wide variety of data is available on the Web that is intended to be processed by a program, rather than displayed directly to the user; the program may be running as part of a back-end application, or may be a script running in the browser. Such data are typically accessed using what is in effect a Web application programming interface; that is, a function call request is sent using the HTTP protocol, executed at an application server, and the results sent back to the calling program. A system that supports such an interface is called a Web service.

Two approaches are widely used to implement Web services. In the simpler approach, called Representation State Transfer (or REST), Web service function calls are executed by a standard HTTP request to a URL at an application server, with parameters sent as standard HTTP request parameters. The application server executes the request (which may involve updating the database at the server), generates and encodes the result, and returns the result as the result of the HTTP request. The server can use any encoding for a particular requested URL; XML, and an encoding of JavaScript objects called JavaScript Object Notation(JSON), are widely used. The requestor parses the returned page to access the returned data.

In many applications of such RESTful Web services (that is, Web services using REST), the requestor is JavaScript code running in a Web browser; the code updates the browser screen using the result of the function call. For example, when you scroll the display on a map interface on the Web, the part of the map that needs to be newly displayed may be fetched by JavaScript code using a RESTful interface, and then displayed on the screen.

A more complex approach, sometimes referred to as “Big Web Services,” uses XML encoding of parameters as well as results, has a formal definition of the Web API using a special language, and uses a protocol layer built on top of the HTTP protocol. This approach is described in more detail in Section 23.7.3.

Disconnected Operation

Many applications wish to support some operations even when a client is dis- connected from the application server. For example, a student may wish to fill an application form even if her laptop is disconnected from the network, but have it saved back when the laptop is reconnected. As another example, if an email client is built as a Web application, a user may wish to compose an email even if her laptop is disconnected from the network, and have it sent when it is reconnected. Building such applications requires local storage, preferably in the form of a database, in the client machine. The Gears software (originally de- veloped by Google) is a browser plug-in that provides a database, a local Web server, and support for parallel execution of JavaScript at the client. The software works identically on multiple operating system/browser platforms, allowing ap- plications to support rich functionality without installation of any software (other than Gears itself). Adobe’s AIR software also provides similar functionality for building Internet applications that can run outside the Web browser.