Storage Attachment

Computers access secondary storage in three ways: via host-attached storage, network-attached storage, and cloud storage.

Host-Attached Storage

Host-attached storage is storage accessed through local I/O ports. These ports use several technologies, the most common being SATA, as mentioned earlier. A typical system has one or a few SATA ports.

To allow a system to gain access to more storage, either an individual storage device, a device in a chassis, or multiple drives in a chassis can be connected via USB FireWire or Thunderbolt ports and cables.

High-end workstations and servers generally need more storage or need to share storage, so use more sophisticated I/O architectures, such as fibr channel (FC), a high-speed serial architecture that can operate over optical fiber or over a four-conductor copper cable. Because of the large address space and the switched nature of the communication, multiple hosts and storage devices can attach to the fabric, allowing great flexibility in I/O communication.

A wide variety of storage devices are suitable for use as host-attached storage. Among these are HDDs; NVM devices; CD, DVD, Blu-ray, and tape drives; and storage-area networks (SANs) (discussed in Section 11.7.4). The I/O commands that initiate data transfers to a host-attached storage device are reads andwrites of logical data blocks directed to specifically identified storage units (such as bus ID or target logical unit).

Network-Attached Storage

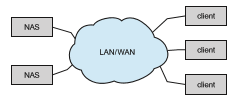

Network-attached storage (NAS) (Figure 11.12) provides access to storage across a network.AnNAS device can be either a special-purpose storage system or a general computer system that provides its storage to other hosts across the network. Clients access network-attached storage via a remote-procedure- call interface such as NFS for UNIX and Linux systems or CIFS for Windows machines. The remote procedure calls (RPCs) are carried via TCP or UDP over an IP network—usually the same local-area network (LAN) that carries all data traffic to the clients. The network-attached storage unit is usually implemented as a storage array with software that implements the RPC interface.

CIFS and NFS provide various locking features, allowing the sharing of files betweenhosts accessing aNASwith those protocols. For example, a user logged in tomultipleNAS clients can access her homedirectory fromall of those clients, simultaneously.

Network-attached storage provides a convenient way for all the computers on a LAN to share a pool of storage with the same ease of naming and access enjoyed with local host-attached storage. However, it tends to be less efficient and have lower performance than some direct-attached storage options.

iSCSI is the latest network-attached storage protocol. In essence, it uses the IP network protocol to carry the SCSI protocol. Thus, networks—rather than SCSI cables—can be used as the interconnects between hosts and their storage. As a result, hosts can treat their storage as if it were directly attached, even if the storage is distant from the host. Whereas NFS and CIFS present a file system and send parts of files across the network, iSCSI sends logical blocks across the network and leaves it to the client to use the blocks directly or create a file system with them.

Cloud Storage

Section 1.10.5 discussed cloud computing. One offering from cloud providers is cloud storage. Similar to network-attached storage, cloud storage provides access to storage across a network. Unlike NAS, the storage is accessed over the Internet or another WAN to a remote data center that provides storage for a fee (or even for free).

Another difference between NAS and cloud storage is how the storage is accessed and presented to users. NAS is accessed as just another file system if the CIFS orNFS protocols are used, or as a rawblock device if the iSCSI protocol is used.Most operating systems have these protocols integrated and present NAS storage in the sameway as other storage. In contrast, cloud storage is API based, and programs use the APIs to access the storage. Amazon S3 is a leading cloud storage offering. Dropbox is an example of a company that provides apps to connect to the cloud storage that it provides. Other examples includeMicrosoft OneDrive and Apple iCloud.

One reason that APIs are used instead of existing protocols is the latency and failure scenarios of a WAN. NAS protocols were designed for use in LANs, which have lower latency thanWANs and aremuch less likely to lose connectiv- ity between the storage user and the storage device. If a LAN connection fails, a system using NFS or CIFS might hang until it recovers. With cloud storage, failures like that are more likely, so an application simply pauses access until connectivity is restored.

Storage-Area Networks and Storage Arrays

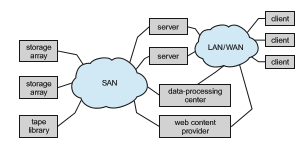

One drawback of network-attached storage systems is that the storage I/O operations consume bandwidth on the data network, thereby increasing the latency of network communication. This problem can be particularly acute in large client–server installations—the communication between servers and clients competes for bandwidth with the communication among servers and storage devices.

Astorage-area network (SAN) is a private network (using storage protocols rather than networking protocols) connecting servers and storage units, as shown in Figure 11.13. The power of a SAN lies in its flexibility. Multiple hosts and multiple storage arrays can attach to the same SAN, and storage can be dynamically allocated to hosts. The storage arrays can be RAID protected or unprotected drives (Just a Bunch of Disks (JBOD)). A SAN switch allows or prohibits access between the hosts and the storage. As one example, if a host is running low on disk space, the SAN can be configured to allocate more storage to that host. SANs make it possible for clusters of servers to share the same storage and for storage arrays to include multiple direct host connections. SANs typically have more ports—and cost more—than storage arrays. SAN connectivity is over short distances and typically has no routing, so a NAS can have many more connected hosts than a SAN.

A storage array is a purpose-built device (see Figure 11.14) that includes SANports, networkports, or both. It also contains drives to store data and a con- troller (or redundant set of controllers) to manage the storage and allow access to the storage across the networks. The controllers are composed of CPUs, memory, and software that implement the features of the array, which can include network protocols, user interfaces, RAID protection, snapshots, repli- cation, compression, deduplication, and encryption. Some of those functions are discussed in Chapter 14.

Some storage arrays include SSDs. An array may contain only SSDs, result- ing in maximum performance but smaller capacity, or may include a mix of SSDs and HDDs, with the array software (or the administrator) selecting the best medium for a given use or using the SSDs as a cache and HDDs as bulk storage.

FC is the most common SAN interconnect, although the simplicity of iSCSI is increasing its use. Another SAN interconnect is InfiniBan (IB)—a special- purpose bus architecture that provides hardware and software support for high-speed interconnection networks for servers and storage units.