RAID Structure

Storage devices have continued to get smaller and cheaper, so it is now eco- nomically feasible to attach many drives to a computer system. Having a large number of drives in a system presents opportunities for improving the rate at which data can be read or written, if the drives are operated in paral- lel. Furthermore, this setup offers the potential for improving the reliability of data storage, because redundant information can be stored on multiple drives. Thus, failure of one drive does not lead to loss of data. A variety of disk-organization techniques, collectively called redundant arrays of inde- pendent disks (RAIDs), are commonly used to address the performance and reliability issues.

In the past, RAIDs composed of small, cheap disks were viewed as a cost- effective alternative to large, expensive disks. Today, RAIDs are used for their higher reliability and higher data-transfer rate rather than for economic rea- sons. Hence, the I in **RAID,**which once stood for “inexpensive,” now stands for “independent.”

Improvement of Reliability via Redundancy

Let’s first consider the reliability of a RAID of HDDs. The chance that some disk out of a set of N disks will fail is much greater than the chance that a specific single disk will fail. Suppose that the mean time between failures (MTBF) of a single disk is 100,000 hours. Then the MTBF of some disk in an array of 100

STRUCTURING RAID

RAID storage can be structured in a variety of ways. For example, a system can have drives directly attached to its buses. In this case, the operating system or system software can implement RAID functionality. Alternatively, an intelligent host controller can control multiple attached devices and can implement RAID on those devices in hardware. Finally, a storage array can be used. A storage array, as just discussed, is a standalone unit with its own controller, cache, anddrives. It is attached to the host via one ormore standard controllers (for example, FC). This common setup allows an operating system or software without RAID functionality to have RAID-protected storage.

disks will be 100,000/100 = 1,000 hours, or 41_._66 days, which is not long at all! If we store only one copy of the data, then each disk failure will result in loss of a significant amount of data—and such a high rate of data loss is unacceptable.

The solution to the problem of reliability is to introduce redundancy; we store extra information that is not normally needed but can be used in the event of disk failure to rebuild the lost information. Thus, even if a disk fails, data are not lost. RAID can be applied to NVM devices as well, although NVM devices have no moving parts and therefore are less likely to fail than HDDs.

The simplest (but most expensive) approach to introducing redundancy is to duplicate every drive. This technique is called mirroring. With mirroring, a logical disk consists of two physical drives, and every write is carried out on both drives. The result is called a mirrored volume. If one of the drives in the volume fails, the data can be read from the other. Data will be lost only if the second drive fails before the first failed drive is replaced.

The MTBF of a mirrored volume—where failure is the loss of data— depends on two factors. One is the MTBF of the individual drives. The other is the mean time to repair, which is the time it takes (on average) to replace a failed drive and to restore the data on it. Suppose that the failures of the two drives are independent; that is, the failure of one is not connected to the failure of the other. Then, if the MTBF of a single drive is 100,000 hours and the mean time to repair is 10 hours, themean time to data loss of amirrored drive system is 100, 0002∕(2 ∗ 10) = 500 ∗ 106 hours, or 57,000 years!

You should be aware that we cannot really assume that drive failures will be independent. Power failures and natural disasters, such as earthquakes, fires, and floods, may result in damage to both drives at the same time. Also, manufacturing defects in a batch of drives can cause correlated failures. As drives age, the probability of failure grows, increasing the chance that a second drive will fail while the first is being repaired. In spite of all these considera- tions, however, mirrored-drive systems offer much higher reliability than do single-drive systems.

Power failures are a particular source of concern, since they occur far more frequently than do natural disasters. Even with mirroring of drives, if writes are in progress to the same block in both drives, and power fails before both blocks are fully written, the two blocks can be in an inconsistent state. One solution to this problem is to write one copy first, then the next. Another is to add a solid-state nonvolatile cache to the RAID array. This write-back cache is protected from data loss during power failures, so the write can be considered complete at that point, assuming the cache has some kind of error protection and correction, such as ECC or mirroring.

Improvement in Performance via Parallelism

Now let’s consider how parallel access to multiple drives improves perfor- mance. With mirroring, the rate at which read requests can be handled is doubled, since read requests can be sent to either drive (as long as both in a pair are functional, as is almost always the case). The transfer rate of each read is the same as in a single-drive system, but the number of reads per unit time has doubled.

With multiple drives, we can improve the transfer rate as well (or instead) by striping data across the drives. In its simplest form, data striping consists of splitting the bits of each byte across multiple drives; such striping is called bit-level striping. For example, if we have an array of eight drives, we write bit i of each byte to drive i. The array of eight drives can be treated as a single drive with sectors that are eight times the normal size and, more important, have eight times the access rate. Every drive participates in every access (read or write); so the number of accesses that can be processed per second is about the same as on a single drive, but each access can read eight times asmany data in the same time as on a single drive.

Bit-level striping can be generalized to include a number of drives that either is a multiple of 8 or divides 8. For example, if we use an array of four drives, bits i and 4+ i of each byte go to drive i. Further, striping need not occur at the bit level. In block-level striping, for instance, blocks of a file are striped across multiple drives; with n drives, block i of a file goes to drive (_i_mod n)+1. Other levels of striping, such as bytes of a sector or sectors of a block, also are possible. Block-level striping is the only commonly available striping.

Parallelism in a storage system, as achieved through striping, has twomain goals:

1. Increase the throughput of multiple small accesses (that is, page accesses) by load balancing.

2. Reduce the response time of large accesses.

RAID Levels

Mirroring provides high reliability, but it is expensive. Striping provides high data-transfer rates, but it does not improve reliability. Numerous schemes to provide redundancy at lower cost by using disk striping combined with “parity” bits (which we describe shortly) have been proposed. These schemes have different cost–performance trade-offs and are classified according to levels called RAID levels. We describe only the most common levels here; Figure 11.15 shows them pictorially (in the figure, P indicates error-correcting bits and C indicates a second copy of the data). In all cases depicted in the figure, four drives’ worth of data are stored, and the extra drives are used to store redundant information for failure recovery.

• RAID level 0. RAID level 0 refers to drive arrays with striping at the level of blocks but without any redundancy (such as mirroring or parity bits), as shown in Figure 11.15(a).

• RAID level 1. RAID level 1 refers to drive mirroring. Figure 11.15(b) shows a mirrored organization.

• RAID level 4. RAID level 4 is also known as memory-style error-correcting- code (ECC) organization. ECC is also used in RAID 5 and 6.

The idea of ECC can be used directly in storage arrays via striping of blocks across drives. For example, the first data block of a sequence of writes can be stored in drive 1, the second block in drive 2, and so on until the _N_th block is stored in drive N; the error-correction calculation result of those blocks is stored on drive N + 1. This scheme is shown in Figure 11.15(c), where the drive labeled P stores the error-correction block. If one of the drives fails, the error-correction code recalculation detects that and prevents the data from being passed to the requesting process, throwing an error.

RAID 4 can actually correct errors, even though there is only one ECC block. It takes into account the fact that, unlike memory systems, drive controllers can detect whether a sector has been read correctly, so a single parity block can be used for error correction and detection. The idea is as follows: If one of the sectors is damaged, we know exactly which sector it is.We disregard the data in that sector and use the parity data to recalculate the bad data. For every bit in the block, we can determine if it is a 1 or a 0 by computing the parity of the corresponding bits from sectors in the other drives. If the parity of the remaining bits is equal to the stored parity, the missing bit is 0; otherwise, it is 1.

A block read accesses only one drive, allowing other requests to be processed by the other drives. The transfer rates for large reads are high, since all the disks can be read in parallel. Large writes also have high transfer rates, since the data and parity can be written in parallel. Small independentwrites cannot be performed in parallel. An operating-system write of data smaller than a block requires that the block be read, modified with the new data, and written back. The parity block has to be updated as well. This is known as the read-modify-write cycle. Thus, a single write requires four drive accesses: two to read the two old blocks and two to write the two new blocks. WAFL (which we cover in Chapter 14) uses RAID level 4 because this RAID level allows drives to be added to a RAID set seamlessly. If the added drives are initializedwith blocks containing only zeros, then the parity value does not change, and the RAID set is still correct.

RAID level 4 has two advantages over level 1 while providing equal data protection. First, the storage overhead is reduced because only one parity drive is needed for several regular drives, whereas one mirror drive is needed for every drive in level 1. Second, since reads and writes of a series of blocks are spread out over multiple drives with N-way striping of data, the transfer rate for reading or writing a set of blocks is N times as fast as with level 1.

A performance problem with RAID 4—and with all parity-based RAID levels—is the expense of computing and writing the XOR parity. This overhead can result in slower writes than with non-parity RAID arrays. Modern general-purpose CPUs are very fast compared with drive I/O, however, so the performance hit can be minimal. Also, many RAID storage arrays or host bus-adapters include a hardware controller with dedicated parity hardware. This controller offloads the parity computation from the CPU to the array. The array has an NVRAM cache as well, to store the blocks while the parity is computed and to buffer the writes from the controller to the drives. Such buffering can avoid most read-modify- write cycles by gathering data to be written into a full stripe and writing to all drives in the stripe concurrently. This combination of hardware acceleration and buffering can make parity RAID almost as fast as non- parity RAID, frequently outperforming a non-caching non-parity RAID.

• RAID level 5. RAID level 5, or block-interleaved distributed parity, differs from level 4 in that it spreads data and parity among all_N_+1 drives, rather than storing data in N drives and parity in one drive. For each set of N blocks, one of the drives stores the parity and the others store data. For example, with an array of five drives, the parity for the _n_th block is stored in drive (_n_mod 5) + 1. The _n_th blocks of the other four drives store actual data for that block. This setup is shown in Figure 11.15(d), where the _P_s are distributed across all the drives. A parity block cannot store parity for blocks in the same drive, because a drive failure would result in loss of data as well as of parity, and hence the loss would not be recoverable. By spreading the parity across all the drives in the set, RAID 5 avoids potential overuse of a single parity drive, which can occur with RAID 4. RAID 5 is the most common parity RAID.

• RAID level 6. RAID level 6, also called the P + Q redundancy scheme, is much like RAID level 5 but stores extra redundant information to guard against multiple drive failures. XOR parity cannot be used on both parity blocks because theywould be identical andwould not providemore recov- ery information. Instead of parity, error-correcting codes such as Galois fiel math are used to calculate Q. In the scheme shown in Figure 11.15(e), 2 blocks of redundant data are stored for every 4 blocks of data—com- paredwith 1 parity block in level 5—and the system can tolerate two drive failures.

• Multidimensional RAID level 6. Some sophisticated storage arrays amplify RAID level 6. Consider an array containing hundreds of drives. Putting those drives in a RAID level 6 stripe would result in many data drives and only two logical parity drives. Multidimensional RAID level 6 logically arranges drives into rows and columns (two ormore dimensional arrays) and implements RAID level 6 both horizontally along the rows and vertically down the columns. The system can recover from any failure —or, indeed, multiple failures—by using parity blocks in any of these locations. This RAID level is shown in Figure 11.15(f). For simplicity, the figure shows the RAID parity on dedicated drives, but in reality the RAID blocks are scattered throughout the rows and columns.

• RAID levels 0 + 1 and 1 + 0. RAID level 0 + 1 refers to a combination of RAID levels 0 and 1. RAID 0 provides the performance, while RAID 1 provides the reliability. Generally, this level provides better performance than RAID 5. It is common in environments where both performance and reliability are important. Unfortunately, like RAID 1, it doubles the number of drives needed for storage, so it is also relatively expensive. In RAID 0 + 1, a set of drives are striped, and then the stripe is mirrored to another, equivalent stripe.

Another RAID variation is RAID level 1 + 0, in which drives are mirrored in pairs and then the resulting mirrored pairs are striped. This scheme has some theoretical advantages over RAID 0 + 1. For example, if a single drive fails in RAID 0 + 1, an entire stripe is inaccessible, leaving only the other stripe. With a failure in RAID 1 + 0, a single drive is unavailable, but the drive that mirrors it is still available, as are all the rest of the drives (Figure 11.16).

Numerous variations have been proposed to the basic RAID schemes described here. As a result, some confusion may exist about the exact definitions of the different RAID levels.

The implementation of RAID is another area of variation. Consider the following layers at which RAID can be implemented.

• Volume-management software can implement RAIDwithin the kernel or at the system software layer. In this case, the storage hardware can provide minimal features and still be part of a full RAID solution.

• RAID can be implemented in the host bus-adapter (HBA) hardware. Only the drives directly connected to the HBA can be part of a given RAID set. This solution is low in cost but not very flexible.

• RAID can be implemented in the hardware of the storage array. The storage array can create RAID sets of various levels and can even slice these sets into smaller volumes, which are then presented to the operating system. The operating system need only implement the file system on each of the volumes. Arrays can have multiple connections available or can be part of a SAN, allowing multiple hosts to take advantage of the array’s features.

• RAID can be implemented in the SAN interconnect layer by drive virtualiza- tion devices. In this case, a device sits between the hosts and the storage. It accepts commands from the servers and manages access to the storage. It could provide mirroring, for example, by writing each block to two separate storage devices.

Other features, such as snapshots and replication, can be implemented at each of these levels as well. A snapshot is a view of the file system before the last update took place. (Snapshots are coveredmore fully inChapter 14.)Repli- cation involves the automatic duplication of writes between separate sites for redundancy and disaster recovery. Replication can be synchronous or asyn- chronous. In synchronous replication, each block must be written locally and remotely before the write is considered complete, whereas in asynchronous replication, the writes are grouped together and written periodically. Asyn- chronous replication can result in data loss if the primary site fails, but it is faster and has no distance limitations. Increasingly, replication is also used within a data center or even within a host. As an alternative to RAID protec- tion, replication protects against data loss and also increases read performance (by allowing reads from each of the replica copies). It does of course use more storage than most types of RAID.

The implementation of these features differs depending on the layer at which RAID is implemented. For example, if RAID is implemented in software, then each host may need to carry out and manage its own replication. If replication is implemented in the storage array or in the SAN interconnect, however, then whatever the host operating system or its features, the host’s data can be replicated.

One other aspect of most RAID implementations is a hot spare drive or drives. A hot spare is not used for data but is configured to be used as a replacement in case of drive failure. For instance, a hot spare can be used to rebuild a mirrored pair should one of the drives in the pair fail. In this way, the RAID level can be reestablished automatically, without waiting for the failed drive to be replaced. Allocating more than one hot spare allows more than one failure to be repaired without human intervention.

Selecting a RAID Level

Given the many choices they have, how do system designers choose a RAID level? One consideration is rebuild performance. If a drive fails, the time needed to rebuild its data can be significant. This may be an important factor if a continuous supply of data is required, as it is in high-performance or interactive database systems. Furthermore, rebuild performance influences the mean time between failures.

Rebuild performance varies with the RAID level used. Rebuilding is easiest for RAID level 1, since data can be copied from another drive. For the other levels, we need to access all the other drives in the array to rebuild data in a failed drive. Rebuild times can be hours for RAID level 5 rebuilds of large drive sets.

RAID level 0 is used in high-performance applications where data loss is not critical. For example, in scientific computing where a data set is loaded and explored, RAID level 0 works well because any drive failures would just require a repair and reloading of the data from its source. RAID level 1 is popular for applications that require high reliability with fast recovery. RAID

THE InServ STORAGE ARRAY

Innovation, in an effort to provide better, faster, and less expensive solutions, frequently blurs the lines that separated previous technologies. Consider the InServ storage array from HP 3Par. Unlike most other storage arrays, InServ does not require that a set of drives be configured at a specific RAID level. Rather, each drive is broken into 256-MB “chunklets.” RAID is then applied at the chunklet level. Adrive can thus participate in multiple and various RAID levels as its chunklets are used for multiple volumes.

In Serv also provides snapshots similar to those created by the WAFL file system. The format of InServ snapshots can be read–write as well as read- only, allowing multiple hosts to mount copies of a given file system without needing their own copies of the entire file system. Any changes a host makes in its own copy are copy-on-write and so are not reflected in the other copies.

A further innovation is utility storage. Some file systems do not expand or shrink. On these systems, the original size is the only size, and any change requires copying data. An administrator can configure InServ to provide a host with a large amount of logical storage that initially occupies only a small amount of physical storage. As the host starts using the storage, unused drives are allocated to the host, up to the original logical level. The host thus can believe that it has a large fixed storage space, create its file systems there, and so on. Drives can be added to or removed from the file system by InServ without the file system’s noticing the change. This feature can reduce the number of drives needed by hosts, or at least delay the purchase of drives until they are really needed.

0 + 1 and 1 + 0 are used where both performance and reliability are important —for example, for small databases. Due to RAID 1’s high space overhead, RAID 5 is often preferred for storing moderate volumes of data. RAID 6 and multidimensional RAID 6 are themost common formats in storage arrays. They offer good performance and protection without large space overhead.

RAID system designers and administrators of storage have to make several other decisions as well. For example, how many drives should be in a given RAID set? Howmany bits should be protected by each parity bit? If more drives are in an array, data-transfer rates are higher, but the system is more expensive. If more bits are protected by a parity bit, the space overhead due to parity bits is lower, but the chance that a second drive will fail before the first failed drive is repaired is greater, and that will result in data loss.

Extensions

The concepts of RAID have been generalized to other storage devices, including arrays of tapes, and even to the broadcast of data over wireless systems. When applied to arrays of tapes, RAID structures are able to recover data even if one of the tapes in an array is damaged.When applied to broadcast of data, a block of data is split into short units and is broadcast along with a parity unit. If one of the units is not received for any reason, it can be reconstructed from the other units. Commonly, tape-drive robots containing multiple tape drives will stripe data across all the drives to increase throughput and decrease backup time.

Problems with RAID

Unfortunately, RAID does not always assure that data are available for the operating system and its users. Apointer to a file could be wrong, for example, or pointers within the file structure could be wrong. Incomplete writes (called “torn writes”), if not properly recovered, could result in corrupt data. Some other process could accidentally write over a file system’s structures, too. RAID protects against physical media errors, but not other hardware and software errors. A failure of the hardware RAID controller, or a bug in the software RAID code, could result in total data loss. As large as is the landscape of software and hardware bugs, that is how numerous are the potential perils for data on a system.

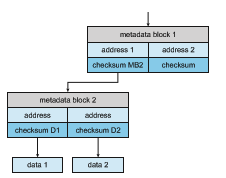

The Solaris ZFS file system takes an innovative approach to solving these problems through the use of checksums. ZFS maintains internal checksums of all blocks, including data and metadata. These checksums are not kept with the block that is being checksummed. Rather, they are stored with the pointer to that block. (See Figure 11.17.) Consider an inode—a data structure for storing file system metadata—with pointers to its data. Within the inode is the checksum of each block of data. If there is a problem with the data, the checksum will be incorrect, and the file system will know about it. If the data are mirrored, and there is a block with a correct checksum and one with an incorrect checksum, ZFS will automatically update the bad block with the good one. Similarly, the directory entry that points to the inode has a check- sum for the inode. Any problem in the inode is detected when the directory is accessed. This checksumming takes places throughout all ZFS structures, providing a much higher level of consistency, error detection, and error cor-

rection than is found in RAID drive sets or standard file systems. The extra overhead that is created by the checksum calculation and extra block read- modify-write cycles is not noticeable because the overall performance of ZFS is very fast. (A similar checksum feature is found in the Linux BTRFS file system. See https://btrfs.wiki.kernel.org/index.php/Btrfs design.)

Another issue with most RAID implementations is lack of flexibility. Con- sider a storage array with twenty drives divided into four sets of five drives. Each set of five drives is a RAID level 5 set. As a result, there are four separate volumes, each holding a file system. But what if one file system is too large to fit on a five-drive RAID level 5 set? And what if another file system needs very little space? If such factors are known ahead of time, then the drives and volumes can be properly allocated. Very frequently, however, drive use and requirements change over time.

Even if the storage array allowed the entire set of twenty drives to be created as one large RAID set, other issues could arise. Several volumes of various sizes could be built on the set. But some volume managers do not allow us to change a volume’s size. In that case, wewould be left with the same issue described above—mismatched file-system sizes. Some volumemanagers allow size changes, but some file systems do not allow for file-system growth or shrinkage. The volumes could change sizes, but the file systemswould need to be recreated to take advantage of those changes.

ZFS combines file-system management and volume management into a unit providing greater functionality than the traditional separation of those functions allows. Drives, or partitions of drives, are gathered together via RAID sets into pools of storage. A pool can hold one or more ZFS file systems. The entire pool’s free space is available to all file systems within that pool. ZFS uses the memory model of malloc() and free() to allocate and release storage for each file system as blocks are used and freed within the file system. As a result, there are no artificial limits on storage use and no need to relocate file systems between volumes or resize volumes. ZFS provides quotas to limit the size of a file system and reservations to assure that a file system can grow by a specified amount, but those variables can be changed by the file-system owner at any time. Other systems like Linux have volumemanagers that allow the logical joining of multiple disks to create larger-than-disk volumes to hold large file systems. Figure 11.18(a) depicts traditional volumes and file systems, and Figure 11.18(b) shows the ZFS model.

Object Storage

General-purpose computers typically use file systems to store content for users. Another approach to data storage is to start with a storage pool and place objects in that pool. This approach differs from file systems in that there is no way to navigate the pool and find those objects. Thus, rather than being user-oriented, object storage is computer-oriented, designed to be used by programs. A typical sequence is:

1. Create an object within the storage pool, and receive an object ID.

2. Access the object when needed via the object ID.

3. Delete the object via the object ID.

Object storage management software, such as the Hadoop fil system (HDFS) and Ceph, determines where to store the objects and manages object protection. Typically, this occurs on commodity hardware rather than RAID arrays. For example, HDFS can store N copies of an object on N different com- puters. This approach can be lower in cost than storage arrays and can provide fast access to that object (at least on those_N_ systems). All systems in a Hadoop cluster can access the object, but only systems that have a copy have fast access via the copy. Computations on the data occur on those systems, with results sent across the network, for example, only to the systems requesting them. Other systems neednetwork connectivity to read andwrite to the object. There- fore, object storage is usually used for bulk storage, not high-speed random access. Object storage has the advantage of horizontal scalability. That is, whereas a storage array has a fixed maximum capacity, to add capacity to an object store, we simply add more computers with internal disks or attached external disks and add them to the pool. Object storage pools can be petabytes in size.

Another key feature of object storage is that each object is self-describing, including description of its contents. In fact, object storage is also known as content-addressable storage, because objects can be retrieved based on their contents. There is no set format for the contents, so what the system stores is unstructured data.

While object storage is not common on general-purpose computers, huge amounts of data are stored in object stores, including Google’s Internet search contents, Dropbox contents, Spotify’s songs, and Facebook photos. Cloud com- puting (such as Amazon AWS) generally uses object stores (in Amazon S3) to hold file systems as well as data objects for customer applications running on cloud computers.

Practice Exercises 485

For the history of object stores see http://www.theregister.co.uk/2016/07/15 /the history boys cas and object storage map.

Summary

• Hard disk drives and nonvolatilememory devices are themajor secondary storage I/O units on most computers. Modern secondary storage is struc- tured as large one-dimensional arrays of logical blocks.

• Drives of either type may be attached to a computer system in one of three ways: (1) through the local I/O ports on the host computer, (2) directly connected to motherboards, or (3) through a communications network or storage network connection.

• Requests for secondary storage I/O are generated by the file system and by the virtual memory system. Each request specifies the address on the device to be referenced in the form of a logical block number.

• Disk-scheduling algorithms can improve the effective bandwidth of HDDs, the average response time, and the variance in response time. Algo- rithms such as SCAN and C-SCAN are designed to make such improve- ments through strategies for disk-queue ordering. Performance of disk- scheduling algorithms can vary greatly on hard disks. In contrast, because solid-state disks have no moving parts, performance varies little among scheduling algorithms, and quite often a simple FCFS strategy is used.

• Data storage and transmission are complex and frequently result in errors. Error detection attempts to spot such problems to alert the system for corrective action and to avoid error propagation. Error correction can detect and repair problems, depending on the amount of correction data available and the amount of data that was corrupted.

• Storage devices are partitioned into one or more chunks of space. Each partition can hold a volume or be part of a multidevice volume. File systems are created in volumes.

• The operating system manages the storage device’s blocks. New devices typically come pre-formatted. The device is partitioned, file systems are created, and boot blocks are allocated to store the system’s bootstrap pro- gram if the device will contain an operating system. Finally, when a block or page is corrupted, the systemmust have a way to lock out that block or to replace it logically with a spare.

• An efficient swap space is a key to good performance in some systems. Some systems dedicate a raw partition to swap space, and others use a file within the file system instead. Still other systems allow the user or system administrator to make the decision by providing both options.

• Because of the amount of storage required on large systems, and because storage devices fail in various ways, secondary storage devices are fre- quently made redundant via RAID algorithms. These algorithms allow more than one drive to be used for a given operation and allow continued operation and even automatic recovery in the face of a drive failure. RAID algorithms are organized into different levels; each level provides some combination of reliability and high transfer rates.

• Object storage is used for big data problems such as indexing the Inter- net and cloud photo storage. Objects are self-defining collections of data, addressed by object ID rather than file name. Typically it uses replication for data protection, computes based on the data on systems where a copy of the data exists, and is horizontally scalable for vast capacity and easy expansion.

Practice Exercises

11.1 Is disk scheduling, other than FCFS scheduling, useful in a single-user environment? Explain your answer.

11.2 Explain why SSTF scheduling tends to favor middle cylinders over the innermost and outermost cylinders.

11.3 Why is rotational latency usually not considered in disk scheduling? How would you modify SSTF, SCAN, and C-SCAN to include latency optimization?

11.4 Why is it important to balance file-system I/O among the disks and controllers on a system in a multitasking environment?

11.5 What are the tradeoffs involved in rereading code pages from the file system versus using swap space to store them?

11.6 Is there any way to implement truly stable storage? Explain your answer.

11.7 It is sometimes said that tape is a sequential-access medium, whereas a hard disk is a random-access medium. In fact, the suitability of a storage device for random access depends on the transfer size. The term streaming transfer rate denotes the rate for a data transfer that is underway, excluding the effect of access latency. In contrast, the effec- tive transfer rate is the ratio of total bytes to total seconds, including overhead time such as access latency.

Suppose we have a computer with the following characteristics: the level-2 cache has an access latency of 8 nanoseconds and a streaming transfer rate of 800 megabytes per second, the main memory has an access latency of 60 nanoseconds and a streaming transfer rate of 80 megabytes per second, the hard disk has an access latency of 15 mil- liseconds and a streaming transfer rate of 5 megabytes per second, and a tape drive has an access latency of 60 seconds and a streaming transfer rate of 2 megabytes per second.

a. Random access causes the effective transfer rate of a device to decrease, because no data are transferred during the access time. For the disk described, what is the effective transfer rate if an average access is followed by a streaming transfer of (1) 512 bytes, (2) 8 kilobytes, (3) 1 megabyte, and (4) 16 megabytes?

b. The utilization of a device is the ratio of effective transfer rate to streaming transfer rate. Calculate the utilization of the disk drive for each of the four transfer sizes given in part a.

c. Suppose that a utilization of 25 percent (or higher) is considered acceptable. Using the performance figures given, compute the smallest transfer size for a disk that gives acceptable utilization.

d. Complete the following sentence: A disk is a random- access device for transfers larger than bytes and is a sequential-access device for smaller transfers.

e. Compute the minimum transfer sizes that give acceptable utiliza- tion for cache, memory, and tape.

f. When is a tape a random-access device, and when is it a sequential-access device?

11.8 Could a RAID level 1 organization achieve better performance for read requests than a RAID level 0 organization (with nonredundant striping of data)? If so, how?

11.9 Give three reasons to use HDDs as secondary storage.

11.10 Give three reasons to use NVM devices as secondary storage.

Further Reading

[Services (2012)] provides an overview of data storage in a variety of modern computing environments. Discussions of redundant arrays of independent disks (RAIDs) are presented by [Patterson et al. (1988)]. [Kim et al. (2009)] discuss disk-scheduling algorithms for SSDs. Object-based storage is described by [Mesnier et al. (2003)].

[Russinovich et al. (2017)], [McDougall and Mauro (2007)], and [Love (2010)] discuss file-systemdetails inWindows, Solaris, and Linux, respectively.

Storage devices are continuously evolving, with goals of increasing perfor- mance, increasing capacity, or both. For one direction in capacity improvement seehttp://www.tomsitpro.com/articles/shingled-magnetic-recoding-smr-101- basics,2-933.html).

RedHat (and other) Linux distributions have multiple, selectable disk scheduling algorithms. For details seehttps://access.redhat.com/site/docume ntation/en-US/Red Hat Enterprise Linux/7/html/Performance Tuning Guide/in dex.html.

Learn more about the default Linux bootstrap loader at https://www.gnu.org/software/grub/manual/grub.html/.

Arelatively newfile system, BTRFS, is detailed in https://btrfs.wiki.kernel.or g/index.php/Btrfs design.

For the history of object stores see http://www.theregister.co.uk/2016/07/15 /the history boys cas and object storage map.

Bibliography

[Kim et al. (2009)] J. Kim, Y. Oh, E. Kim, J. C. D. Lee, and S. Noh, “Disk Sched- ulers for Solid State Drivers”, Proceedings of the seventh ACM international confer- ence on Embedded software (2009), pages 295–304.

[Love (2010)] R. Love, Linux Kernel Development, Third Edition, Developer’s Library (2010).

[McDougall and Mauro (2007)] R. McDougall and J. Mauro, Solaris Internals, Second Edition, Prentice Hall (2007).

[Mesnier et al. (2003)] M. Mesnier, G. Ganger, and E. Ridel, “Object-based stor- age”, IEEE Communications Magazine, Volume 41, Number 8 (2003), pages 84–99.

[Patterson et al. (1988)] D. A. Patterson, G. Gibson, and R. H. Katz, “A Case for Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks (RAID)”, Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD International Conference on the Management of Data (1988), pages 109– 116.

[Russinovich et al. (2017)] M.Russinovich,D.A. Solomon, andA. Ionescu,Win- dows Internals–Part 1, Seventh Edition, Microsoft Press (2017).

[Services (2012)] E. E. Services, Information Storage and Management: Storing, Managing, and Protecting Digital Information in Classic, Virtualized, and Cloud Envi- ronments, Wiley (2012).

Chapter 11 Exercises

11.11 None of the disk-scheduling disciplines, except FCFS, is truly fair (star- vation may occur).

a. Explain why this assertion is true.

b. Describe a way to modify algorithms such as SCAN to ensure fairness.

c. Explainwhy fairness is an important goal in amulti-user systems.

d. Give three or more examples of circumstances in which it is important that the operating system be unfair in serving I/O requests.

11.12 ExplainwhyNVMdevices often use an FCFS disk-scheduling algorithm.

11.13 Suppose that a disk drive has 5,000 cylinders, numbered 0 to 4,999. The drive is currently serving a request at cylinder 2,150, and the previous request was at cylinder 1,805. The queue of pending requests, in FIFO order, is:

2,069; 1,212; 2,296; 2,800; 544; 1,618; 356; 1,523; 4,965; 3,681

Starting from the current head position, what is the total distance (in cylinders) that the disk arm moves to satisfy all the pending requests for each of the following disk-scheduling algorithms?

a. FCFS

b. SCAN

c. C-SCAN

11.14 Elementary physics states that when an object is subjected to a constant acceleration a, the relationship between distance d and time t is given by d = 1

2 _at_2. Suppose that, during a seek, the disk in Exercise 11.14

accelerates the disk arm at a constant rate for the first half of the seek, then decelerates the disk arm at the same rate for the second half of the seek. Assume that the disk can perform a seek to an adjacent cylinder in 1 millisecond and a full-stroke seek over all 5,000 cylinders in 18 milliseconds.

a. The distance of a seek is the number of cylinders over which the head moves. Explain why the seek time is proportional to the square root of the seek distance.

b. Write an equation for the seek time as a function of the seek distance. This equation should be of the form t = x+y

√ L, where t

is the time in milliseconds and L is the seek distance in cylinders.

c. Calculate the total seek time for each of the schedules in Exercise 11.14. Determine which schedule is the fastest (has the smallest total seek time).

EX-43

Exercises

d. The percentage speedup is the time saved divided by the original time. What is the percentage speedup of the fastest schedule over FCFS?

11.15 Suppose that the disk in Exercise 11.15 rotates at 7,200 RPM.

a. What is the average rotational latency of this disk drive?

b. What seek distance can be covered in the time that you found for part a?

11.16 Compare and contrast HDDs and NVM devices.What are the best appli- cations for each type?

11.17 Describe some advantages and disadvantages of using NVM devices as a caching tier and as a disk-drive replacement compared with using only HDDs.

11.18 Compare the performance of C-SCAN and SCAN scheduling, assum- ing a uniform distribution of requests. Consider the average response time (the time between the arrival of a request and the completion of that request’s service), the variation in response time, and the effective bandwidth. Howdoes performance depend on the relative sizes of seek time and rotational latency?

11.19 Requests are not usually uniformly distributed. For example, we can expect a cylinder containing the file-system metadata to be accessed more frequently than a cylinder containing only files. Suppose you know that 50 percent of the requests are for a small, fixed number of cylinders.

a. Would any of the scheduling algorithms discussed in this chapter be particularly good for this case? Explain your answer.

b. Propose a disk-scheduling algorithm that gives even better per- formance by taking advantage of this “hot spot” on the disk.

11.20 Consider a RAID level 5 organization comprising five disks, with the parity for sets of four blocks on four disks stored on the fifth disk. How many blocks are accessed in order to perform the following?

a. Awrite of one block of data

b. Awrite of seven continuous blocks of data

11.21 Compare the throughput achieved by a RAID level 5 organization with that achieved by a RAID level 1 organization for the following:

a. Read operations on single blocks

b. Read operations on multiple contiguous blocks

11.22 Compare the performance of write operations achieved by a RAID level 5 organization with that achieved by a RAID level 1 organization.

11.23 Assume that you have a mixed configuration comprising disks orga- nized as RAID level 1 and RAID level 5 disks. Assume that the system has flexibility in deciding which disk organization to use for storing a

EX-44

particular file. Which files should be stored in the RAID level 1 disks and which in the RAID level 5 disks in order to optimize performance?

11.24 The reliability of a storage device is typically described in terms ofmean time between failures (MTBF). Although this quantity is called a “time,” the MTBF actually is measured in drive-hours per failure.

a. If a system contains 1,000 disk drives, each ofwhich has a 750,000- hour MTBF, which of the following best describes how often a drive failurewill occur in that disk farm: once per thousand years, once per century, once per decade, once per year, once per month, once per week, once per day, once per hour, once per minute, or once per second?

b. Mortality statistics indicate that, on the average, a U.S. resident has about 1 chance in 1,000 of dying between the ages of 20 and 21. Deduce the MTBF hours for 20-year-olds. Convert this figure from hours to years. What does this MTBF tell you about the expected lifetime of a 20-year-old?

c. The manufacturer guarantees a 1-million-hour MTBF for a certain model of disk drive. What can you conclude about the number of years for which one of these drives is under warranty?

11.25 Discuss the relative advantages and disadvantages of sector sparing and sector slipping.

11.26 Discuss the reasons why the operating system might require accurate information on how blocks are stored on a disk. How could the operat- ing system improve file-system performance with this knowledge?

EX-45

Chapter 11 Mass-Storage Structure

Programming Problems

11.27 Write a program that implements the following disk-scheduling algo- rithms:

a. FCFS

b. SCAN

c. C-SCAN

Your program will service a disk with 5,000 cylinders numbered 0 to 4,999. The program will generate a random series of 1,000 cylinder requests and service them according to each of the algorithms listed above. The program will be passed the initial position of the disk head (as a parameter on the command line) and report the total amount of head movement required by each algorithm.