Kernel I/O Subsystem

Kernels provide many services related to I/O. Several services—scheduling, buffering, caching, spooling, device reservation, and error handling—are pro- vided by the kernel’s I/O subsystem and build on the hardware and device- driver infrastructure. The I/O subsystem is also responsible for protecting itself from errant processes and malicious users.

I/O Scheduling

To schedule a set of I/O requests means to determine a good order in which to execute them. The order in which applications issue system calls rarely is the best choice. Scheduling can improve overall system performance, can share device access fairly among processes, and can reduce the average waiting time for I/O to complete. Here is a simple example to illustrate. Suppose that a disk arm is near the beginning of a disk and that three applications issue blocking read calls to that disk. Application 1 requests a block near the end of the disk, application 2 requests one near the beginning, and application 3 requests one in themiddle of the disk. The operating system can reduce the distance that the disk arm travels by serving the applications in the order 2, 3, 1. Rearranging the order of service in this way is the essence of I/O scheduling.

Operating-system developers implement scheduling by maintaining a wait queue of requests for each device. When an application issues a blocking I/O system call, the request is placed on the queue for that device. The I/O scheduler rearranges the order of the queue to improve the overall system effi- ciency and the average response time experienced by applications. The operat- ing systemmay also try to be fair, so that no one application receives especially poor service, or it may give priority service for delay-sensitive requests. For instance, requests from the virtual memory subsystem may take priority over application requests. Several scheduling algorithms for disk I/O were detailed in Section 11.2.

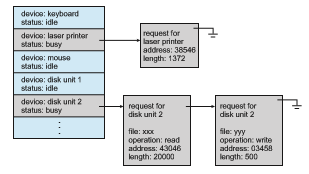

When a kernel supports asynchronous I/O, it must be able to keep track of many I/O requests at the same time. For this purpose, the operating system might attach the wait queue to a device-status table. The kernel manages this table, which contains an entry for each I/O device, as shown in Figure 12.10. Each table entry indicates the device’s type, address, and state (not functioning,

idle, or busy). If the device is busy with a request, the type of request and other parameters will be stored in the table entry for that device.

Scheduling I/O operations is oneway inwhich the I/O subsystem improves the efficiency of the computer. Another way is by using storage space in main memory or elsewhere in the storage hierarchy via buffering, caching, and spooling.

Buffering

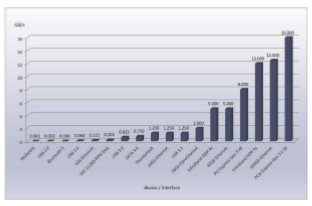

Abuffer, of course, is amemory area that stores data being transferred between two devices or between a device and an application. Buffering is done for three reasons. One reason is to cope with a speed mismatch between the producer and consumer of a data stream. Suppose, for example, that a file is being received via Internet for storage on an SSD. The network speed may be a thousand times slower than the drive. So a buffer is created in main memory to accumulate the bytes received from the network. When an entire buffer of data has arrived, the buffer can be written to the drive in a single operation. Since the drivewrite is not instantaneous and the network interface still needs a place to store additional incoming data, two buffers are used.After the network fills the first buffer, the drive write is requested. The network then starts to fill the second buffer while the first buffer is written to storage. By the time the network has filled the second buffer, the drive write from the first one should have completed, so the network can switch back to the first buffer while the drive writes the second one. This double buffering decouples the producer of data from the consumer, thus relaxing timing requirements between them. The need for this decoupling is illustrated in Figure 12.11, which lists the enormous differences in device speeds for typical computer hardware and interfaces.

A second use of buffering is to provide adaptations for devices that have different data-transfer sizes. Such disparities are especially common in computer networking, where buffers are used widely for fragmentation and

reassembly of messages. At the sending side, a large message is fragmented into small network packets. The packets are sent over the network, and the receiving side places them in a reassembly buffer to form an image of the source data.

A third use of buffering is to support copy semantics for application I/O. An example will clarify the meaning of “copy semantics.” Suppose that an application has a buffer of data that it wishes to write to disk. It calls the write() systemcall, providing a pointer to the buffer and an integer specifying the number of bytes to write. After the system call returns, what happens if the application changes the contents of the buffer? With copy semantics, the version of the data written to disk is guaranteed to be the version at the time of the application system call, independent of any subsequent changes in the application’s buffer. A simple way in which the operating system can guarantee copy semantics is for the write() system call to copy the application data into a kernel buffer before returning control to the application. The disk write is performed from the kernel buffer, so that subsequent changes to the application buffer have no effect. Copying of data between kernel buffers and application data space is common in operating systems, despite the overhead that this operation introduces, because of the clean semantics. The same effect can be obtained more efficiently by clever use of virtual memory mapping and copy-on-write page protection.

Caching

A cache is a region of fast memory that holds copies of data. Access to the cached copy is more efficient than access to the original. For instance, the instructions of the currently running process are stored on disk, cached in physicalmemory, and copied again in the CPU’s secondary andprimary caches.

The difference between a buffer and a cache is that a buffer may hold the only existing copy of a data item, whereas a cache, by definition, holds a copy on faster storage of an item that resides elsewhere.

Caching and buffering are distinct functions, but sometimes a region of memory can be used for both purposes. For instance, to preserve copy seman- tics and to enable efficient scheduling of disk I/O, the operating system uses buffers in main memory to hold disk data. These buffers are also used as a cache, to improve the I/O efficiency for files that are shared by applications or that are being written and reread rapidly. When the kernel receives a file I/O request, the kernel first accesses the buffer cache to see whether that region of the file is already available in main memory. If it is, a physical disk I/O can be avoided or deferred. Also, disk writes are accumulated in the buffer cache for several seconds, so that large transfers are gathered to allow efficient write schedules. This strategy of delaying writes to improve I/O efficiency is discussed, in the context of remote file access, in Section 19.8.

Spooling and Device Reservation

A spool is a buffer that holds output for a device, such as a printer, that cannot accept interleaved data streams. Although a printer can serve only one job at a time, several applicationsmaywish to print their output concurrently, without having their output mixed together. The operating system solves this problem by intercepting all output to the printer. Each application’s output is spooled to a separate secondary storage file. When an application finishes printing, the spooling system queues the corresponding spool file for output to the printer. The spooling system copies the queued spool files to the printer one at a time. In some operating systems, spooling is managed by a system daemon process. In others, it is handled by an in-kernel thread. In either case, the operating system provides a control interface that enables users and system administrators to display the queue, remove unwanted jobs before those jobs print, suspend printing while the printer is serviced, and so on.

Some devices, such as tape drives and printers, cannot usefully multiplex the I/O requests of multiple concurrent applications. Spooling is one way operating systems can coordinate concurrent output. Anotherway to dealwith concurrent device access is to provide explicit facilities for coordination. Some operating systems (including VMS) provide support for exclusive device access by enabling a process to allocate an idle device and to deallocate that device when it is no longer needed. Other operating systems enforce a limit of one open file handle to such a device. Many operating systems provide functions that enable processes to coordinate exclusive access among themselves. For instance, Windows provides system calls to wait until a device object becomes available. It also has a parameter to the OpenFile() system call that declares the types of access to be permitted to other concurrent threads. On these systems, it is up to the applications to avoid deadlock.

Error Handling

An operating system that uses protected memory can guard against many kinds of hardware and application errors, so that a complete system failure is not the usual result of each minor mechanical malfunction. Devices and I/O transfers can fail inmanyways, either for transient reasons, as when a network becomes overloaded, or for “permanent” reasons, as when a disk controller becomes defective. Operating systems can often compensate effectively for transient failures. For instance, a disk read() failure results in a read() retry, and a network send() error results in a resend(), if the protocol so specifies. Unfortunately, if an important component experiences a permanent failure, the operating system is unlikely to recover.

As a general rule, an I/O system call will return one bit of information about the status of the call, signifying either success or failure. In the UNIX operating system, an additional integer variable named errno is used to return an error code—one of about a hundred values—indicating the general nature of the failure (for example, argument out of range, bad pointer, or file not open). By contrast, some hardware can provide highly detailed error infor- mation, although many current operating systems are not designed to convey this information to the application. For instance, a failure of a SCSI device is reported by the SCSI protocol in three levels of detail: a sense key that iden- tifies the general nature of the failure, such as a hardware error or an illegal request; an additional sense code that states the category of failure, such as a bad command parameter or a self-test failure; and an additional sense-code qualifie that gives even more detail, such as which command parameter was in error or which hardware subsystem failed its self-test. Further, many SCSI devices maintain internal pages of error-log information that can be requested by the host—but seldom are.

I/O Protection

Errors are closely related to the issue of protection. A user process may acci- dentally or purposely attempt to disrupt the normal operation of a system by attempting to issue illegal I/O instructions. We can use various mechanisms to ensure that such disruptions cannot take place in the system.

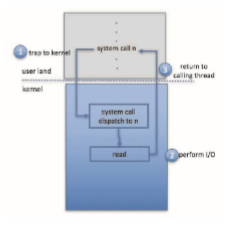

To prevent users from performing illegal I/O, we define all I/O instructions to be privileged instructions. Thus, users cannot issue I/O instructions directly; they must do it through the operating system. To do I/O, a user program executes a system call to request that the operating system perform I/O on its behalf (Figure 12.12). The operating system, executing inmonitormode, checks that the request is valid and, if it is, does the I/O requested. The operating system then returns to the user.

In addition, any memory-mapped and I/O port memory locations must be protected from user access by the memory-protection system. Note that a kernel cannot simply deny all user access. Most graphics games and video editing and playback software need direct access to memory-mapped graphics controller memory to speed the performance of the graphics, for example. The kernel might in this case provide a locking mechanism to allow a section of graphics memory (representing a window on screen) to be allocated to one process at a time.

Kernel Data Structures

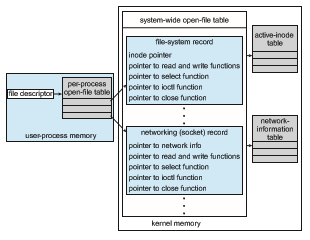

The kernel needs to keep state information about the use of I/O components. It does so through a variety of in-kernel data structures, such as the open-file table

structure discussed in Section 14.1. The kernel uses many similar structures to track network connections, character-device communications, and other I/O activities.

UNIX provides file-system access to a variety of entities, such as user files, raw devices, and the address spaces of processes. Although each of these entities supports a read() operation, the semantics differ. For instance, to read a user file, the kernel needs to probe the buffer cache before deciding whether to perform a disk I/O. To read a raw disk, the kernel needs to ensure that the request size is a multiple of the disk sector size and is aligned on a sector boundary. To read a process image, it is merely necessary to copy data from memory. UNIX encapsulates these differences within a uniform structure by using an object-oriented technique. The open-file record, shown in Figure 12.13, contains a dispatch table that holds pointers to the appropriate routines, depending on the type of file.

Some operating systems use object-oriented methods even more exten- sively. For instance, Windows uses a message-passing implementation for I/O. An I/O request is converted into a message that is sent through the kernel to the I/O manager and then to the device driver, each of which may change the message contents. For output, the message contains the data to be written. For input, the message contains a buffer to receive the data. The message-passing approach can add overhead, by comparison with procedural techniques that use shared data structures, but it simplifies the structure and design of the I/O system and adds flexibility.

Power Management

Computers residing in data centers may seem far removed from issues of power use, but as power costs increase and the world becomes increasingly troubled about the long-term effects of greenhouse gas emissions, data cen- ters have become a cause for concern and a target for increased efficiencies. Electricity use generates heat, and computer components can fail due to high temperatures, so cooling is part of the equation as well. Consider that cool- ing a modern data center may use twice as much electricity as powering the equipment does. Many approaches to data-center power optimization are in use, ranging from interchanging data-center air without side air, chilling with natural sources such as lake water, and solar panels.

Operating systems play a role in power use (and therefore heat gener- ation and cooling). In cloud computing environments, processing loads can be adjusted by monitoring and management tools to evacuate all user pro- cesses from systems, idling those systems and powering them off until the load requires their use. An operating system could analyze its load and, if suf- ficiently low and hardware-enabled, power off components such as CPUsand external I/O devices.

CPU cores can be suspended when the system load does not require them and resumed when the load increases and more cores are needed to run the queue of threads. Their state, of course, needs to be saved on suspend and restored on resume. This feature is needed in servers because a data center full of servers can use vast amounts of electricity, and disabling unneeded cores can decrease electricity (and cooling) needs.

In mobile computing, power management becomes a high-priority aspect of the operating system.Minimizing power use and therefore maximizing bat- tery life increases the usability of a device and helps it competewith alternative devices. Today’s mobile devices offer the functionality of yesterday’s high- end desktop, yet are powered by batteries and are small enough to fit in your pocket. In order to provide satisfactory battery life, modern mobile operating systems are designed from the ground up with power management as a key feature. Let’s examine in detail three major features that enable the popular Android mobile system to maximize battery life: power collapse, component- level power management, and wakelocks.

Power collapse is the ability to put a device into a very deep sleep state. The device uses only marginally more power than if it were fully powered off, yet it is still able to respond to external stimuli, such as the user pressing a button, at which time it quickly powers back on. Power collapse is achieved by powering off many of the individual components within a device—such as the screen, speakers, and I/O subsystem—so that they consume no power. The operating system then places the CPU in its lowest sleep state. Amodern ARM CPU might consume hundreds of milliwatts per core under typical load yet only a handful of milliwatts in its lowest sleep state. In such a state, although the CPU is idle, it can receive an interrupt, wake up, and resume its previous activity very quickly. Thus, an idle Android phone in your pocket uses very little power, but it can spring to life when it receives a phone call.

How is Android able to turn off the individual components of a phone? How does it know when it is safe to power off the flash storage, and how does it know to do that before powering down the overall I/O subsystem? The answer is component-level powermanagement, which is an infrastructure that understands the relationship between components and whether each compo- nent is in use. To understand the relationship between components, Android builds a device tree that represents the phone’s physical-device topology. For example, in such a topology, flash and USB storage would be sub-nodes of the I/O subsystem, which is a sub-node of the system bus, which in turn connects to the CPU. To understand usage, each component is associated with its device driver, and the driver tracks whether the component is in use—for example, if there is I/O pending to flash or if an application has an open reference to the audio subsystem. With this information, Android can manage the power of the phone’s individual components: If a component is unused, it is turned off. If all of the components on, say, the system bus are unused, the system bus is turned off. And if all of the components in the entire device tree are unused, the system may enter power collapse.

With these technologies, Android can aggressively manage its power con- sumption. But a final piece of the solution ismissing: the ability for applications to temporarily prevent the system from entering power collapse. Consider a user playing a game, watching a video, or waiting for a web page to open. In all of these cases, the application needs a way to keep the device awake, at least temporarily. Wakelocks enable this functionality. Applications acquire and release wakelocks as needed. While an application holds a wakelock, the kernel will prevent the system from entering power collapse. For example, while theAndroidMarket is updating an application, it will hold awakelock to ensure that the system does not go to sleep until the update is complete. Once complete, the Android Market will release the wakelock, allowing the system to enter power collapse.

Power management in general is based on device management, which is more complicated than we have so far portrayed it. At boot time, the firmware systemanalyzes the systemhardware and creates a device tree in RAM. The ker- nel then uses that device tree to load device drivers andmanage devices.Many additional activities pertaining to devices must be managed, though, includ- ing addition and subtraction of devices from a running system (“hot-plug”), understanding and changing device states, and power management. Modern general-purpose computers use another set of firmware code, advanced con- figuratio and power interface (ACPI), to manage these aspects of hardware. ACPI is an industry standard (http://www.acpi.info) with many features. It pro- vides code that runs as routines callable by the kernel for device state discovery and management, device error management, and power management. For example, when the kernel needs to quiesce a device, it calls the device driver, which calls the ACPI routines, which then talk to the device.

Kernel I/O Subsystem Summary

In summary, the I/O subsystem coordinates an extensive collection of services that are available to applications and to other parts of the kernel. The I/O subsystem supervises these procedures:

• Management of the name space for files and devices

• Access control to files and devices

• Operation control (for example, a modem cannot seek())

• File-system space allocation

• Device allocation

• Buffering, caching, and spooling

• I/O scheduling

• Device-status monitoring, error handling, and failure recovery

• Device-driver configuration and initialization

• Power management of I/O devices

The upper levels of the I/O subsystem access devices via the uniform interface provided by the device drivers.

12.5 Transforming I/O Requests to Hardware Operations

Earlier, we described the handshaking between a device driver and a device controller, but we did not explain how the operating system connects an appli- cation request to a set of network wires or to a specific disk sector. Consider,for example, reading a file from disk. The application refers to the data by a file name. Within a disk, the file system maps from the file name through the file-system directories to obtain the space allocation of the file. For instance, in MS-DOS for FAT (a relatively simple operating and file system still used today as a common interchange format), the name maps to a number that indicates an entry in the file-access table, and that table entry tells which disk blocks are allocated to the file. In UNIX, the name maps to an inode number, and the corresponding inode contains the space-allocation information. But how is the connection made from the file name to the disk controller (the hardware port address or the memory-mapped controller registers)?

One method is that used by MS-DOS for FAT, mentioned above. The first part of an MS-DOS file name, preceding the colon, is a string that identifies a specific hardware device. For example, C: is the first part of every file name on the primary hard disk. The fact that C: represents the primary hard disk is built into the operating system; C: is mapped to a specific port address through a device table. Because of the colon separator, the device name space is separate from the file-system name space. This separationmakes it easy for the operating system to associate extra functionalitywith eachdevice. For instance, it is easy to invoke spooling on any files written to the printer.

If, instead, the device name space is incorporated in the regular file-system name space, as it is in UNIX, the normal file-system name services are provided automatically. If the file system provides ownership and access control to all file names, then devices have owners and access control. Since files are stored on devices, such an interface provides access to the I/O system at two levels. Names can be used to access the devices themselves or to access the files stored on the devices.

UNIX represents device names in the regular file-system name space. Unlike anMS-DOS FAT file name,which has a colon separator, a UNIX path name has no clear separation of the device portion. In fact, no part of the path name is the name of a device. UNIX has a mount table that associates prefixes of path names with specific device names. To resolve a path name, UNIX looks up the name in themount table to find the longest matching prefix; the corresponding entry in the mount table gives the device name. This device name also has the formof a name in the file-systemname space.WhenUNIX looks up this name in the file-systemdirectory structures, it finds not an inode number but a_<major, minor>_ device number. The major device number identifies a device driver that should be called to handle I/O to this device. The minor device number is passed to the device driver to index into a device table. The corresponding device-table entry gives the port address or the memory-mapped address of the device controller.

Modern operating systems gain significant flexibility from the multiple stages of lookup tables in the path between a request and a physical device con- troller. The mechanisms that pass requests between applications and drivers are general. Thus, we can introduce new devices and drivers into a com- puter without recompiling the kernel. In fact, some operating systems have the ability to load device drivers on demand. At boot time, the system first probes the hardware buses to determine what devices are present. It then loads the necessary drivers, either immediately or when first required by an I/O request. Devices added after boot can be detected by the error they cause (interrupt-generatedwith no associated interrupt handler, for example), which can prompt the kernel to inspect the device details and load an appropri- ate device driver dynamically. Of course, dynamic loading (and unloading) is more complicated than static loading, requiring more complex kernel algo- rithms, device-structure locking, error handling, and so forth.

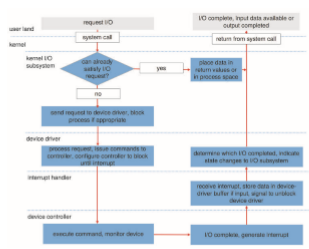

We next describe the typical life cycle of a blocking read request, as depicted in Figure 12.14. The figure suggests that an I/O operation requires a greatmany steps that together consume a tremendous number of CPU cycles.

1. Aprocess issues a blocking read() system call to a file descriptor of a file that has been opened previously.

2. The system-call code in the kernel checks the parameters for correctness. In the case of input, if the data are already available in the buffer cache, the data are returned to the process, and the I/O request is completed.

3. Otherwise, a physical I/O must be performed. The process is removed from the run queue and is placed on thewait queue for the device, and the I/O request is scheduled. Eventually, the I/O subsystem sends the request to the device driver. Depending on the operating system, the request is sent via a subroutine call or an in-kernel message.

4. The device driver allocates kernel buffer space to receive the data and schedules the I/O. Eventually, the driver sends commands to the device controller by writing into the device-control registers.

5. The device controller operates the device hardware to perform the data transfer.

6. The driver may poll for status and data, or it may have set up a DMA transfer into kernel memory. We assume that the transfer is managed by a DMA controller, which generates an interrupt when the transfer completes.

7. The correct interrupt handler receives the interrupt via the interrupt- vector table, stores any necessary data, signals the device driver, and returns from the interrupt.

8. The device driver receives the signal, determines which I/O request has completed, determines the request’s status, and signals the kernel I/O subsystem that the request has been completed.

9. The kernel transfers data or return codes to the address space of the requesting process and moves the process from the wait queue back to the ready queue.

10. Moving the process to the ready queue unblocks the process. When the scheduler assigns the process to the CPU, the process resumes execution at the completion of the system call.