Program Threats

Processes, along with the kernel, are the only means of accomplishing work on a computer. Therefore, writing a program that creates a breach of security, or causing a normal process to change its behavior and create a breach, is a common goal of attackers. In fact, evenmost nonprogram security events have as their goal causing a program threat. For example, while it is useful to log in to a system without authorization, it is quite a lot more useful to leave behind a back-door daemon or Remote Access Tool (RAT) that provides information or allows easy access even if the original exploit is blocked. In this section, we describe common methods by which programs cause security breaches. Note that there is considerable variation in the naming conventions for security holes and that we use the most common or descriptive terms.

Malware

Malware is software designed to exploit, disable or damage computer systems. There are many ways to perform such activities, and we explore the major variations in this section.

Many systems have mechanisms for allowing programs written by a user to be executed by other users. If these programs are executed in a domain that provides the access rights of the executing user, the other users may misuse these rights. A program that acts in a clandestine or malicious manner, rather than simply performing its stated function, is called a Trojan horse. If the pro- gram is executed in another domain, it can escalate privileges. As an example, consider a mobile app that purports to provide some benign functionality— say, a flashlight app—but that meanwhile surreptitiously accesses the user’s contacts or messages and smuggles them to some remote server.

A classic variation of the Trojan horse is a “Trojan mule” program that emulates a login program. An unsuspecting user starts to log in at a terminal, computer, or web page and notices that she has apparently mistyped her password. She tries again and is successful. What has happened is that her authentication key and password have been stolen by the login emulator, which was left running on the computer by the attacker or reached via a bad URL. The emulator stored away the password, printed out a login error message, and exited; the user was then provided with a genuine login prompt. This type of attack can be defeated by having the operating system print a usagemessage at the end of an interactive session, by requiring a nontrappable key sequence to get to the login prompt, such as the control-alt-delete combination used by all modern Windows operating systems, or by the user ensuring the URL is the right, valid one.

Another variation on the Trojan horse is spyware. Spyware sometimes accompanies a program that the user has chosen to install. Most frequently, it comes along with freeware or shareware programs, but sometimes it is included with commercial software. Spyware may download ads to display on the user’s system, create pop-up browser windows when certain sites are visited, or capture information from the user’s system and return it to a central site. The installation of an innocuous-seeming program on a Windows system could result in the loading of a spyware daemon. The spyware could contact a central site, be given a message and a list of recipient addresses, and deliver a spam message to those users from the Windows machine. This process would continue until the user discovered the spyware. Frequently, the spyware is not discovered. In 2010, it was estimated that 90 percent of spam was being delivered by this method. This theft of service is not even considered a crime in most countries!

A fairly recent and unwelcome development is a class of malware that doesn’t steal information.Ransomware encrypts some or all of the information on the target computer and renders it inaccessible to the owner. The informa- tion itself has little value to the attacker but lots of value to the owner. The idea is to force the owner to pay money (the ransom) to get the decryption key needed to decrypt the data. As with other dealings with criminals, of course, payment of the ransom does not guarantee return of access.

Trojans and other malware especially thrive in cases where there is a vio- lation of the principle of least privilege. This commonly occurs when the operating systemallows bydefaultmore privileges than a normal user needs or when the user runs by default as an administrator (as was true in all Windows operating systems up to Windows 7). In such cases, the operating system’s own immune system—permissions and protections of various kinds—can- not “kick in,” so the malware can persist and survive across reboot, as well as extend its reach both locally and over the network.

Violating the principle of least privilege is a case of poor operating-system design decision making. An operating system (and, indeed, software in gen- eral) should allow fine-grained control of access and security, so that only the privileges needed to perform a task are available during the task’s execution. The control featuremust also be easy tomanage and understand. Inconvenient, inadequate, and misunderstood security measures are bound to be circum- vented, causing an overall weakening of the security they were designed to implement.

In yet another form ofmalware, the designer of a program or system leaves a hole in the software that only she is capable of using. This type of security breach, a trap door (or back door), was shown in the movie War Games. For

THE PRINCIPLE OF LEAST PRIVILEGE

“The principle of least privilege. Every program and every privileged user of the system should operate using the least amount of privilege necessary to complete the job. The purpose of this principle is to reduce the number of potential interactions among privileged programs to the minimum necessary to operate correctly, so that one may develop confidence that unintentional, unwanted, or improper uses of privilege do not occur.”—Jerome H. Saltzer, describing a design principle of the Multics operating system in 1974: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ 1c8d/06510ad449ad24fbdd164f8008cc730cab47.pdf.

instance, the code might check for a specific user ID or password, and it might circumvent normal security procedures when it receives that ID or password. Programmers have used the trap-door method to embezzle from banks by including rounding errors in their code and having the occasional half-cent credited to their accounts. This account crediting can add up to a large amount of money, considering the number of transactions that a large bank executes.

A trap door may be set to operate only under a specific set of logic condi- tions, in which case it is referred to as a logic bomb. Back doors of this type are especially difficult to detect, as theymay remain dormant for a long time, possi- bly years, before being detected—usually after the damage has been done. For example, one network administrator had a destructive reconfiguration of his company’s network execute when his program detected that he was no longer employed at the company.

A clever trap door could be included in a compiler. The compiler could generate standard object code as well as a trap door, regardless of the source code being compiled. This activity is particularly nefarious, since a search of the source code of the program will not reveal any problems. Only reverse engineering of the code of the compiler itself would reveal this trap door. This type of attack can also be performed by patching the compiler or compile-time libraries after the fact. Indeed, in 2015, malware that targets Apple’s XCode compiler suite (dubbed “XCodeGhost”) affected many software developers who used compromised versions of XCode not downloaded directly from Apple.

Trap doors pose a difficult problem because, to detect them, we have to analyze all the source code for all components of a system. Given that soft- ware systems may consist of millions of lines of code, this analysis is not done frequently, and frequently it is not done at all! A software development methodology that can help counter this type of security hole is code review. In code review, the developer who wrote the code submits it to the code base, and one or more developers review the code and approve it or pro- vide comments. Once a defined set of reviewers approve the code (sometimes after comments are addressed and the code is resubmitted and re-reviewed), the code is admitted into the code base and then compiled, debugged, and finally released for use. Many good software developers use development ver- sion control systems that provide tools for code review—for example, git (https://github.com/git/). Note, too, that there are automatic code-review and

#include <stdio.h>

#define BUFFER SIZE 0

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int j = 0; char buffer[BUFFER SIZE];

int k = 0;

if (argc < 2)

{return -1;}

strcpy(buffer,argv[1]);

printf("K is %d, J is %d, buffer is %s∖n", j,k,buffer);

return 0;

}

Figure 16.2 C program with buffer-overflow condition.

code-scanning tools designed to find flaws, including security flaws, but gen- erally good programmers are the best code reviewers.

For those not involved in developing the code, code review is useful for finding and reporting flaws (or for finding and exploiting them). For most software, source code is not available, making code review much harder for nondevelopers.

Code Injection

Most software is not malicious, but it can nonetheless pose serious threats to security due to a code-injection attack, in which executable code is added or modified. Even otherwise benign software can harbor vulnerabilities that, if exploited, allow an attacker to take over the program code, subverting its existing code flow or entirely reprogramming it by supplying new code.

Code-injection attacks are nearly always the result of poor or insecure programming paradigms, commonly in low-level languages such as C or C++, which allow direct memory access through pointers. This direct mem- ory access, coupled with the need to carefully decide on sizes of memory buffers and take care not to exceed them, can lead to memory corruption when memory buffers are not properly handled.

As an example, consider the simplest code-injection vector—a buffer over- flow. The program in Figure 16.2 illustrates such an overflow,which occurs due to an unbounded copy operation, the call to strcpy(). The function copies with no regard to the buffer size in question, halting only when a NULL (∖0) byte is encountered. If such a byte occurs before the BUFFER SIZE is reached, the program behaves as expected. But the copy could easily exceed the buffer size—what then?

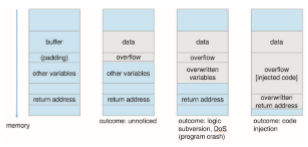

The answer is that the outcome of an overflow depends largely on the length of the overflow and the overflowing contents (Figure 16.3). It also varies greatly with the code generated by the compiler, which may be optimized

in ways that affect the outcome: optimizations often involve adjustments to memory layout (commonly, repositioning or padding variables).

1. If the overflow is very small (only a little more than BUFFER SIZE), there is a good chance it will go entirely unnoticed. This is because the allocation of BUFFER SIZE bytes will often be padded to an architecture-specified boundary (commonly 8 or 16 bytes). Padding is unused memory, and therefore an overflow into it, though technically out of bounds, has no ill effect.

2. If the overflow exceeds the padding, the next automatic variable on the stack will be overwritten with the overflowing contents. The outcome here will depend on the exact positioning of the variable and on its semantics (for example, if it is employed in a logical condition that can then be subverted). If uncontrolled, this overflow could lead to a program crash, as an unexpected value in a variable could lead to an uncorrectable error.

3. If the overflow greatly exceeds the padding, all of the current function’s stack frame is overwritten. At the very top of the frame is the function’s return address, which is accessed when the function returns. The flow of the program is subverted and can be redirected by the attacker to another region of memory, including memory controlled by the attacker (for example, the input buffer itself, or the stack or the heap). The injected code is then executed, allowing the attacker to run arbitrary code as the processes’ effective ID.

Note that a careful programmer could have performed bounds checking on the size of argv[1] by using the strncpy() function rather than strcpy(), replacing the line “strcpy(buffer, argv[1]);” with “strncpy(buffer, argv[1], sizeof(buffer)-1);”. Unfortunately, good bounds checking is the exception rather than the norm. strcpy() is one of a known class of vulner- able functions, which include sprintf(), gets(), and other functions with no regard to buffer sizes. But even size-aware variants can harbor vulnerabilities when coupled with arithmetic operations over finite-length integers, which may lead to an integer overflow.

At this point, the dangers inherent in a simple oversight in maintaining a buffer should be clearly evident. Brian Kerningham and Dennis Ritchie (in their book The C Programming Language) referred to the possible outcome as “undefined behavior,” but perfectly predictable behavior can be coerced by an attacker, as was first demonstrated by the Morris Worm (and documented in RFC1135: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc1135). It was not until several years later, however, that an article in issue 49 of Phrack magazine (“Smashing the Stack for Fun and Profit” http://phrack.org/issues/49/14.html) introduced the exploitation technique to the masses, unleashing a deluge of exploits.

To achieve code injection, there must first be injectable code. The attacker first writes a short code segment such as the following:

void func (void) _{_

execvp(“/bin/sh”, “/bin/sh”, NULL); ; _}_

Using the execvp() system call, this code segment creates a shell process. If the program being attacked runs with root permissions, this newly created shell will gain complete access to the system. Of course, the code segment can do anything allowed by the privileges of the attacked process. The code segment is next compiled into its assembly binary opcode form and then transformed into a binary stream. The compiled form is often referred to as shellcode, due to its classic function of spawning a shell, but the term has grown to encompass any type of code, includingmore advanced code used to add newusers to a system, reboot, or even connect over the network and wait for remote instructions (called a “reverse shell”). A shellcode exploit is shown in Figure 16.4. Code that is briefly used, only to redirect execution to some other location, is much like a trampoline, “bouncing” code flow from one spot to another.

There are, in fact, shellcode compilers (the “MetaSploit” project being a notable example), which also take care of such specifics as ensuring that the code is compact and contains no NULL bytes (in case of exploitation via string copy, which would terminate on NULLs). Such a compiler may even mask the shellcode as alphanumeric characters.

If the attacker has managed to overwrite the return address (or any func- tion pointer, such as that of a VTable), then all it takes (in the simple case) is to redirect the address to point to the supplied shellcode, which is commonly loaded as part of the user input, through an environment variable, or over some file or network input. Assuming no mitigations exist (as described later), this is enough for the shellcode to execute and the hacker to succeed in the attack. Alignment considerations are often handled by adding a sequence of NOP instructions before the shellcode. The result is known as a NOP-sled, as it causes execution to “slide” down the NOP instructions until the payload is encountered and executed.

This example of a buffer-overflow attack reveals that considerable knowl- edge and programming skill are needed to recognize exploitable code and then to exploit it. Unfortunately, it does not take great programmers to launch security attacks. Rather, one hacker can determine the bug and then write an exploit. Anyone with rudimentary computer skills and access to the exploit— a so-called script kiddie—can then try to launch the attack at target systems.

The buffer-overflow attack is especially pernicious because it can be run between systems and can travel over allowed communication channels. Such attacks can occur within protocols that are expected to be used to communicate with the target machine, and they can therefore be hard to detect and prevent. They can even bypass the security added by firewalls (Section 16.6.6).

Note that buffer overflows are just one of several vectors which can be manipulated for code injection. Overflows can also be exploited when they occur in the heap. Using memory buffers after freeing them, as well as over- freeing them (calling free() twice), can also lead to code injection.

Viruses and Worms

Another form of program threat is a virus. Avirus is a fragment of code embed- ded in a legitimate program. Viruses are self-replicating and are designed to “infect” other programs. They can wreak havoc in a system by modifying or destroying files and causing system crashes and program malfunctions. As with most penetration attacks (direct attacks on a system), viruses are very specific to architectures, operating systems, and applications. Viruses are a par- ticular problem for users of PCs. UNIX and other multiuser operating systems generally are not susceptible to viruses because the executable programs are protected from writing by the operating system. Even if a virus does infect such a program, its powers usually are limited because other aspects of the system are protected.

Viruses are usually borne via spam e-mail and phishing attacks. They can also spread when users download viral programs from Internet file-sharing services or exchange infected disks. Adistinction can bemade between viruses, which require human activity, and worms, which use a network to replicate without any help from humans.

For an example of how a virus “infects” a host, consider Microsoft Office files. These files can contain macros (or Visual Basic programs) that programs in the Office suite (Word, PowerPoint, and Excel) will execute automatically. Because these programs run under the user’s own account, the macros can run largely unconstrained (for example, deleting user files at will). The following code sample shows how simple it is to write a Visual Basic macro that a worm could use to format the hard drive of a Windows computer as soon as the file containing the macro was opened:

Sub AutoOpen() Dim oFS

Set oFS = CreateObject(”Scripting.FileSystemObject”) vs = Shell(”c: command.com /k format c:”,vbHide)

End Sub

Commonly, the worm will also e-mail itself to others in the user’s contact list. How do viruses work? Once a virus reaches a target machine, a program

known as a virus dropper inserts the virus into the system. The virus dropper is usually a Trojan horse, executed for other reasons but installing the virus as its core activity. Once installed, the virus may do any one of a number of things. There are literally thousands of viruses, but they fall into several main categories. Note that many viruses belong to more than one category.

• File. A standard file virus infects a system by appending itself to a file. It changes the start of the program so that execution jumps to its code. After it executes, it returns control to the program so that its execution is not noticed. File viruses are sometimes known as parasitic viruses, as they leave no full files behind and leave the host program still functional.

• Boot. A boot virus infects the boot sector of the system, executing every time the system is booted and before the operating system is loaded. It watches for other bootable media and infects them. These viruses are also known as memory viruses, because they do not appear in the file system. Figure 16.5 shows how a boot virus works. Boot viruses have also adapted to infect firmware, such as network card PXE and Extensible Firmware Interface (EFI) environments.

• Macro. Most viruses are written in a low-level language, such as assembly or C. Macro viruses are written in a high-level language, such as Visual Basic. These viruses are triggered when a program capable of executing the macro is run. For example, a macro virus could be contained in a spreadsheet file.

• Rootkit. Originally coined to describe back doors on UNIX systemsmeant to provide easy root access, the term has since expanded to viruses and malware that infiltrate the operating system itself. The result is complete system compromise; no aspect of the system can be deemed trusted.When malware infects the operating system, it can take over all of the system’s functions, including those functions that would normally facilitate its own detection.

• Source code. A source code virus looks for source code and modifies it to include the virus and to help spread the virus.

• Polymorphic. A polymorphic virus changes each time it is installed to avoid detection by antivirus software. The changes do not affect the virus’s functionality but rather change the virus’s signature. A virus signature is a pattern that can be used to identify a virus, typically a series of bytes that make up the virus code.

• Encrypted. An encrypted virus includes decryption code along with the encrypted virus, again to avoid detection. The virus first decrypts and then executes.

• Stealth. This tricky virus attempts to avoid detection by modifying parts of the system that could be used to detect it. For example, it could modify the read system call so that if the file it has modified is read, the original form of the code is returned rather than the infected code.

• Multipartite. Avirus of this type is able to infectmultiple parts of a system, including boot sectors, memory, and files. This makes it difficult to detect and contain.

• Armored. An armored virus is obfuscated—that is, written so as to be hard for antivirus researchers to unravel and understand. It can also be com- pressed to avoid detection and disinfection. In addition, virus droppers and other full files that are part of a virus infestation are frequently hidden via file attributes or unviewable file names.

This vast variety of viruses has continued to grow. For example, in 2004 a widespread virus was detected. It exploited three separate bugs for its oper- ation. This virus started by infecting hundreds of Windows servers (includ- ing many trusted sites) running Microsoft Internet Information Server (IIS). Any vulnerable Microsoft Explorer web browser visiting those sites received a browser virus with any download. The browser virus installed several back-door programs, including a keystroke logger, which records everything entered on the keyboard (including passwords and credit-card numbers). It also installed a daemon to allow unlimited remote access by an intruder and another that allowed an intruder to route spam through the infected desktop computer.

An active security-related debate within the computing community con- cerns the existence of a monoculture, in which many systems run the same hardware, operating system, and application software. This monoculture sup- posedly consists of Microsoft products. One question is whether such a mono- culture even exists today. Another question is whether, if it does, it increases the threat of and damage caused by viruses and other security intrusions. Vul- nerability information is bought and sold in places like the dark web (World Wide Web systems reachable via unusual client configurations or methods). The more systems an attack can affect, the more valuable the attack.