Capability-Based Systems

The concept of capability-based protection was introduced in the early 1970s. Two early research systems were Hydra and CAP. Neither system was widely used, but both provided interesting proving grounds for protection theories. For more details on these systems, see Section A.14.1 and Section A.14.2. Here, we consider two more contemporary approaches to capabilities.

Linux Capabilities

Linux uses capabilities to address the limitations of the UNIX model, which we described earlier. The POSIX standards group introduced capabilities in POSIX 1003.1e. Although POSIX.1e was eventually withdrawn, Linux was quick to adopt capabilities in Version 2.2 and has continued to add new developments.

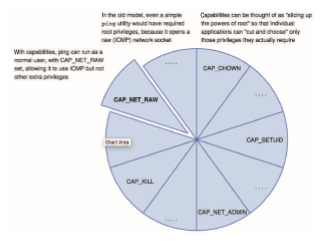

In essence, Linux’s capabilities “slice up” the powers of root into distinct areas, each represented by a bit in a bitmask, as shown in Figure 17.11. Fine- grained control over privileged operations can be achieved by toggling bits in the bitmask.

In practice, three bitmasks are used—denoting the capabilities permitted, effective, and inheritable. Bitmasks can apply on a per-process or a per-thread basis. Furthermore, once revoked, capabilities cannot be reacquired. The usual

sequence of events is that a process or thread startswith the full set of permitted capabilities and voluntarily decreases that set during execution. For example, after opening a network port, a thread might remove that capability so that no further ports can be opened.

You can probably see that capabilities are a direct implementation of the principle of least privilege. As explained earlier, this tenet of security dictates that an application or user must be given only those rights than are required for its normal operation.

Android (which is based on Linux) also utilizes capabilities, which enable system processes (notably, “system server”), to avoid root ownership, instead selectively enabling only those operations required.

The Linux capabilities model is a great improvement over the traditional UNIX model, but it still is inflexible. For one thing, using a bitmap with a bit representing each capability makes it impossible to add capabilities dynami- cally and requires recompiling the kernel to add more. In addition, the feature applies only to kernel-enforced capabilities.

Darwin Entitlements

Apple’s system protection takes the form of entitlements. Entitlements are declaratory permissions—XML property list stating which permissions are claimed as necessary by the program (see Figure 17.12). When the process attempts a privileged operation (in the figure, loading a kernel extension), its

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd"> <plist version="1.0"> <dict>

<key>com.apple.private.kernel.get-kext-info <true/> <key>com.apple.rootless.kext-management <true/>

</dict> </plist>

Figure 17.12 Apple Darwin entitlements

entitlements are checked, and only if the needed entitlements are present is the operation allowed.

To prevent programs from arbitrarily claiming an entitlement, Apple embeds the entitlements in the code signature (explained in Section 17.11.4). Once loaded, a process has no way of accessing its code signature. Other processes (and the kernel) can easily query the signature, and in particular the entitlements. Verifying an entitlement is therefore a simple string-matching operation. In this way, only verifiable, authenticated apps may claim entitlements. All system entitlements (com.apple.*) are further restricted to Apple’s own binaries.