Operating-System Examples

At this point, we have examined a number of concepts and issues related to threads. We conclude the chapter by exploring how threads are implemented in Windows and Linux systems.

Windows Threads

A Windows application runs as a separate process, and each process may contain one or more threads. The Windows API for creating threads is covered in Section 4.4.2. Additionally,Windows uses the one-to-onemapping described in Section 4.3.2, where each user-level thread maps to an associated kernel thread.

The general components of a thread include:

• A thread ID uniquely identifying the thread

• A register set representing the status of the processor

• Aprogram counter

• A user stack, employed when the thread is running in user mode, and a kernel stack, employed when the thread is running in kernel mode

• Aprivate storage area used by various run-time libraries and dynamic link libraries (DLLs)

The register set, stacks, and private storage area are known as the context of the thread.

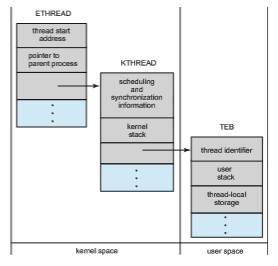

The primary data structures of a thread include:

• ETHREAD—executive thread block

• KTHREAD—kernel thread block

• TEB—thread environment block

The key components of the ETHREAD include a pointer to the process to which the thread belongs and the address of the routine in which the thread starts control. The ETHREAD also contains a pointer to the corresponding KTHREAD.

The KTHREAD includes scheduling and synchronization information for the thread. In addition, the KTHREAD includes the kernel stack (used when the thread is running in kernel mode) and a pointer to the TEB.

The ETHREAD and the KTHREAD exist entirely in kernel space; this means that only the kernel can access them. The TEB is a user-space data structure that is accessed when the thread is running in user mode. Among other fields, the TEB contains the thread identifier, a user-mode stack, and an array for thread-local storage. The structure of a Windows thread is illustrated in Figure 4.21.

Linux Threads

Linux provides the fork() system call with the traditional functionality of duplicating a process, as described in Chapter 3. Linux also provides the ability to create threads using the clone() system call. However, Linux does not distinguish between processes and threads. In fact, Linux uses the term task —rather than process or thread— when referring to a flow of control within a program.

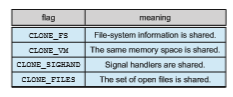

When clone() is invoked, it is passed a set of flags that determine how much sharing is to take place between the parent and child tasks. Some of these flags are listed in Figure 4.22. For example, suppose that clone() is passed the flags CLONE FS, CLONE VM, CLONE SIGHAND, and CLONE FILES. The parent and child tasks will then share the same file-system information (such as the current working directory), the same memory space, the same signal handlers,

and the same set of open files. Using clone() in this fashion is equivalent to creating a thread as described in this chapter, since the parent task shares most of its resources with its child task. However, if none of these flags is set when clone() is invoked, no sharing takes place, resulting in functionality similar to that provided by the fork() system call.

The varying level of sharing is possible because of the way a task is repre- sented in the Linux kernel. Aunique kernel data structure (specifically, struct task struct) exists for each task in the system. This data structure, instead of storing data for the task, contains pointers to other data structures where these data are stored—for example, data structures that represent the list of open files, signal-handling information, and virtual memory. When fork() is invoked, a new task is created, along with a copy of all the associated data structures of the parent process. A new task is also created when the clone() system call is made. However, rather than copying all data structures, the new task points to the data structures of the parent task, depending on the set of flags passed to clone().

Finally, the flexibility of the clone() system call can be extended to the concept of containers, a virtualization topic which was introduced in Chapter 1. Recall from that chapter that a container is a virtualization technique pro- vided by the operating system that allows creating multiple Linux systems (containers) under a single Linux kernel that run in isolation to one another. Just as certain flags passed to clone() can distinguish between creating a task that behaves more like a process or a thread based upon the amount of sharing between the parent and child tasks, there are other flags that can be passed to clone() that allow a Linux container to be created. Containers will be covered more fully in Chapter 18.