Process Concept

A question that arises in discussing operating systems involves what to call all the CPU activities. Early computers were batch systems that executed jobs, followed by the emergence of time-shared systems that ran user programs, or tasks. Even on a single-user system, a usermay be able to run several programs at one time: a word processor, a web browser, and an e-mail package. And even if a computer can execute only one program at a time, such as on an embedded device that does not support multitasking, the operating system may need to support its own internal programmed activities, such asmemorymanagement. Inmany respects, all these activities are similar, sowe call all of themprocesses.

Although we personally prefer the more contemporary term process, the term job has historical significance, as much of operating system theory and terminologywas developedduring a timewhen themajor activity of operating systems was job processing. Therefore, in some appropriate instances we use **job**when describing the role of the operating system. As an example, it would be misleading to avoid the use of commonly accepted terms that include the word job (such as job scheduling) simply because process has superseded job.

The Process

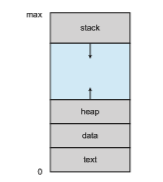

Informally, asmentioned earlier, a process is a program in execution. The status of the current activity of a process is represented by the value of the program counter and the contents of the processor’s registers. The memory layout of a process is typically divided into multiple sections, and is shown in Figure 3.1. These sections include:

• Text section—the executable code

• Data section—global variables

• Heap section—memory that is dynamically allocated during program run time

• Stack section—temporary data storage when invoking functions (such as function parameters, return addresses, and local variables)

Notice that the sizes of the text and data sections are fixed, as their sizes do not change during program run time.However, the stack and heap sections can shrink and grow dynamically during program execution. Each time a function is called, an activation record containing function parameters, local variables, and the return address is pushed onto the stack; when control is returned from the function, the activation record is popped from the stack. Similarly, the heap will grow as memory is dynamically allocated, and will shrink when memory is returned to the system. Although the stack and heap sections grow toward one another, the operating systemmust ensure theydonot**overlap** one another.

We emphasize that a program by itself is not a process. A program is a passive entity, such as a file containing a list of instructions stored on disk (often called an executable fil ). In contrast, a process is an active entity, with a program counter specifying the next instruction to execute and a set of associated resources. A program becomes a process when an executable file is loaded into memory. Two common techniques for loading executable files are double-clicking an icon representing the executable file and entering the name of the executable file on the command line (as in prog.exe or a.out).

Although two processes may be associated with the same program, they are nevertheless considered two separate execution sequences. For instance, several users may be running different copies of the mail program, or the same user may invoke many copies of the web browser program. Each of these is a separate process; and although the text sections are equivalent, the data, heap, and stack sections vary. It is also common to have a process that spawns many processes as it runs. We discuss such matters in Section 3.4.

Note that a process can itself be an execution environment for other code. The Java programming environment provides a good example. In most cir- cumstances, an executable Java program is executed within the Java virtual machine (JVM). The JVM executes as a process that interprets the loaded Java code and takes actions (via native machine instructions) on behalf of that code. For example, to run the compiled Java program Program.class, we would enter

java Program

The command java runs the JVM as an ordinary process, which in turns executes the Java program Program in the virtual machine. The concept is the same as simulation, except that the code, instead of beingwritten for a different instruction set, is written in the Java language.

Process State

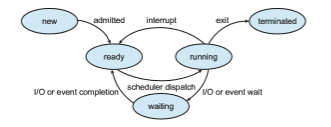

As a process executes, it changes state. The state of a process is defined in part by the current activity of that process. Aprocess may be in one of the following states:

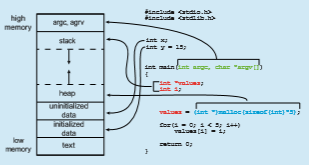

MEMORY LAYOUT OF AC PROGRAM

The figure shown below illustrates the layout of a C program in memory, highlighting how the different sections of a process relate to an actual C program. This figure is similar to the general concept of a process in memory as shown in Figure 3.1, with a few differences:

• The global data section is divided into different sections for (a) initialized data and (b) uninitialized data.

• Aseparate section is provided for the argc and argv parameters passed to the main() function.

text data bss dec hex filename 1158 284 8 1450 5aa memory

The data field refers to uninitialized data, and bss refers to initialized data. (bss is a historical term referring to block started by symbol.) The dec and hex values are the sum of the three sections represented in decimal and hexadecimal, respectively.

• New. The process is being created.

• Running. Instructions are being executed.

• Waiting. The process is waiting for some event to occur (such as an I/O completion or reception of a signal).

• Ready. The process is waiting to be assigned to a processor.

Figure 3.2 Diagram of process state.

• Terminated. The process has finished execution.

These names are arbitrary, and they vary across operating systems. The states that they represent are found on all systems, however. Certain operating sys- tems also more finely delineate process states. It is important to realize that only one process can be running on any processor core at any instant. Many processesmay be ready and_waiting,_ however. The state diagram corresponding to these states is presented in Figure 3.2.

Process Control Block

Each process is represented in the operating system by a process control block (PCB)—also called a task control block. A PCB is shown in Figure 3.3. It contains many pieces of information associated with a specific process, including these:

• Process state. The state may be new, ready, running, waiting, halted, and so on.

• Program counter. The counter indicates the address of the next instruction to be executed for this process.

Figure 3.3 Process control block (PCB).

• CPU registers. The registers vary in number and type, depending on the computer architecture. They include accumulators, index registers, stack pointers, and general-purpose registers, plus any condition-code informa- tion. Alongwith the program counter, this state informationmust be saved when an interrupt occurs, to allow the process to be continued correctly afterward when it is rescheduled to run.

• CPU-scheduling information. This information includes a process prior- ity, pointers to scheduling queues, and any other scheduling parameters. (Chapter 5 describes process scheduling.)

• Memory-management information. This information may include such items as the value of the base and limit registers and the page tables, or the segment tables, depending on the memory system used by the operating system (Chapter 9).

• Accounting information. This information includes the amount of CPU and real time used, time limits, account numbers, job or process numbers, and so on.

• I/O status information. This information includes the list of I/O devices allocated to the process, a list of open files, and so on.

In brief, the PCB simply serves as the repository for all the data needed to start, or restart, a process, along with some accounting data.

Threads

The processmodel discussed so far has implied that a process is a program that performs a single thread of execution. For example, when a process is running a word-processor program, a single thread of instructions is being executed. This single thread of control allows the process to perform only one task at a time. Thus, the user cannot simultaneously type in characters and run the spell checker. Most modern operating systems have extended the process concept to allow a process to have multiple threads of execution and thus to perform more than one task at a time. This feature is especially beneficial on multicore systems, where multiple threads can run in parallel. A multithreaded word processor could, for example, assign one thread to manage user input while another thread runs the spell checker. On systems that support threads, the PCB is expanded to include information for each thread. Other changes throughout the system are also needed to support threads. Chapter 4 explores threads in detail.