Operations on Processes

The processes in most systems can execute concurrently, and they may be cre- ated and deleted dynamically. Thus, these systems must provide a mechanism for process creation and termination. In this section, we explore the mecha- nisms involved in creating processes and illustrate process creation on UNIX and Windows systems.

Process Creation

During the course of execution, a processmay create several new processes. As mentioned earlier, the creating process is called a parent process, and the new processes are called the children of that process. Each of these new processes may in turn create other processes, forming a tree of processes.

Most operating systems (including UNIX, Linux, and Windows) identify processes according to a unique process identifie (or pid), which is typically an integer number. The pid provides a unique value for each process in the system, and it can be used as an index to access various attributes of a process within the kernel.

Figure 3.7 illustrates a typical process tree for the Linux operating system, showing the name of each process and its pid. (We use the term process rather loosely in this situation, as Linux prefers the term task instead.) The systemd process (which always has a pid of 1) serves as the root parent process for all user processes, and is the first user process created when the system boots. Once the system has booted, the systemd process creates processes which provide additional services such as a web or print server, an ssh server, and the like. In Figure 3.7, we see two children of systemd—logind and sshd. The logind process is responsible for managing clients that directly log onto the system. In this example, a client has logged on and is using the bash shell, which has been assigned pid 8416. Using the bash command-line interface, this user has created the process ps as well as the vim editor. The sshd process is responsible for managing clients that connect to the system by using ssh (which is short for secure shell).

THE init AND systemd PROCESSES

Traditional UNIX systems identify the process init as the root of all child processes. init (also known as System V init) is assigned a pid of 1, and is the first process created when the system is booted. On a process tree similar to what is shown in Figure 3.7, init is at the root.

Linux systems initially adopted the System V init approach, but recent distributions have replaced it with systemd. As described in Section 3.3.1, systemd serves as the system’s initial process, much the same as System V init; however it is much more flexible, and can provide more services, than init.

On UNIX and Linux systems, we can obtain a listing of processes by using the ps command. For example, the command

ps -el

will list complete information for all processes currently active in the system. A process tree similar to the one shown in Figure 3.7 can be constructed by recursively tracing parent processes all the way to the systemd process. (In addition, Linux systems provide the pstree command, which displays a tree of all processes in the system.)

In general, when a process creates a child process, that child process will need certain resources (CPU time, memory, files, I/O devices) to accomplish its task. A child process may be able to obtain its resources directly from the operating system, or it may be constrained to a subset of the resources of the parent process. The parent may have to partition its resources among its children, or it may be able to share some resources (such as memory or files) among several of its children. Restricting a child process to a subset of the parent’s resources prevents any process from overloading the system by creating too many child processes.

In addition to supplying various physical and logical resources, the parent process may pass along initialization data (input) to the child process. For example, consider a processwhose function is to display the contents of a file— say, hw1.c—on the screen of a terminal.When the process is created, it will get, as an input from its parent process, the name of the file hw1.c. Using that file name, it will open the file and write the contents out. It may also get the name of the output device. Alternatively, some operating systems pass resources to child processes. On such a system, the new process may get two open files, hw1.c and the terminal device, and may simply transfer the datum between the two.

When a process creates a new process, two possibilities for execution exist:

1. The parent continues to execute concurrently with its children.

2. The parent waits until some or all of its children have terminated.

There are also two address-space possibilities for the new process:

1. The child process is a duplicate of the parent process (it has the same program and data as the parent).

2. The child process has a new program loaded into it.

To illustrate these differences, let’s first consider the UNIX operating system. In UNIX, as we’ve seen, each process is identified by its process identifier, which is a unique integer. A new process is created by the fork() system call. The new process consists of a copy of the address space of the original process. This mechanism allows the parent process to communicate easilywith its child process. Both processes (the parent and the child) continue execution at the instruction after the fork(), with one difference: the return code for the fork() is zero for the new (child) process, whereas the (nonzero) process identifier of the child is returned to the parent.

After a fork() system call, one of the two processes typically uses the exec() system call to replace the process’s memory space with a new pro- gram. The exec() system call loads a binary file into memory (destroying the memory image of the program containing the exec() system call) and starts

its execution. In this manner, the two processes are able to communicate and then go their separate ways. The parent can then create more children; or, if it has nothing else to do while the child runs, it can issue a wait() system call to move itself off the ready queue until the termination of the child. Because the call to exec() overlays the process’s address space with a new program, exec() does not return control unless an error occurs.

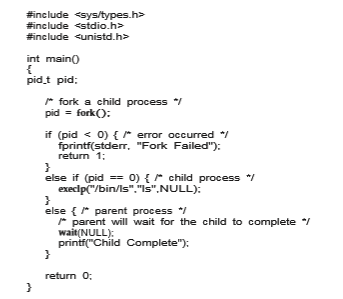

The C program shown in Figure 3.8 illustrates the UNIX system calls pre- viously described. We now have two different processes running copies of the same program. The only difference is that the value of the variable pid for the child process is zero, while that for the parent is an integer value greater than zero (in fact, it is the actual pid of the child process). The child process inherits privileges and scheduling attributes from the parent, as well certain resources, such as open files. The child process then overlays its address space with the UNIX command /bin/ls (used to get a directory listing) using the execlp() system call (execlp() is a version of the exec() system call). The parent waits for the child process to complete with the wait() system call. When the child process completes (by either implicitly or explicitly invoking exit()), the par- ent process resumes from the call to wait(), where it completes using the exit() system call. This is also illustrated in Figure 3.9.

Of course, there is nothing to prevent the child from not invoking exec() and instead continuing to execute as a copy of the parent process. In this scenario, the parent and child are concurrent processes running the same code instructions. Because the child is a copy of the parent, each process has its own copy of any data.

As an alternative example, we next consider process creation in Windows. Processes are created in the Windows API using the CreateProcess() func- tion, which is similar to fork() in that a parent creates a new child process. However, whereas fork() has the child process inheriting the address space of its parent, CreateProcess() requires loading a specified program into the address space of the child process at process creation. Furthermore, whereas fork() is passed no parameters, CreateProcess() expects no fewer than ten parameters.

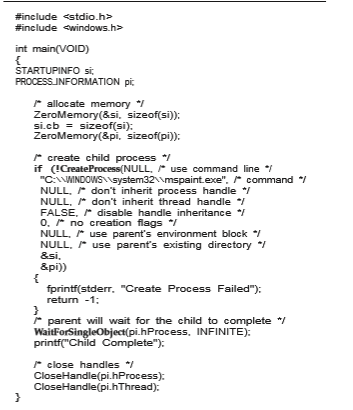

The C program shown in Figure 3.10 illustrates the CreateProcess() function, which creates a child process that loads the application mspaint.exe. We opt for many of the default values of the ten parameters passed to Cre- ateProcess(). Readers interested in pursuing the details of process creation and management in the Windows API are encouraged to consult the biblio- graphical notes at the end of this chapter.

The two parameters passed to the CreateProcess() function are instances of the STARTUPINFO and PROCESS INFORMATION structures. STARTUPINFO specifies many properties of the new process, such as window

size and appearance and handles to standard input and output files. The PROCESS INFORMATION structure contains a handle and the identifiers to the newly created process and its thread. We invoke the ZeroMemory() function to allocate memory for each of these structures before proceeding with CreateProcess().

The first two parameters passed to CreateProcess() are the application name and command-line parameters. If the application name is NULL (as it is in this case), the command-line parameter specifies the application to load.

In this instance, we are loading the Microsoft Windows mspaint.exe appli- cation. Beyond these two initial parameters, we use the default parameters for inheriting process and thread handles aswell as specifying that therewill be no creation flags.We also use the parent’s existing environment block and starting directory. Last, we provide two pointers to the STARTUPINFO and PROCESS - INFORMATION structures created at the beginning of the program. In Figure 3.8, the parent process waits for the child to complete by invoking the wait() system call. The equivalent of this in Windows is WaitForSingleObject(), which is passed a handle of the child process—pi.hProcess—and waits for this process to complete. Once the child process exits, control returns from the WaitForSingleObject() function in the parent process.

Process Termination

A process terminates when it finishes executing its final statement and asks the operating system to delete it by using the exit() system call. At that point, the process may return a status value (typically an integer) to its waiting parent process (via the wait() system call). All the resources of the process —including physical and virtual memory, open files, and I/O buffers—are deallocated and reclaimed by the operating system.

Termination can occur in other circumstances as well. A process can cause the termination of another process via an appropriate system call (for example, TerminateProcess() inWindows). Usually, such a system call can be invoked only by the parent of the process that is to be terminated. Otherwise, a user— or a misbehaving application—could arbitrarily kill another user’s processes. Note that a parent needs to know the identities of its children if it is to terminate them. Thus, when one process creates a new process, the identity of the newly created process is passed to the parent.

A parent may terminate the execution of one of its children for a variety of reasons, such as these:

• The child has exceeded its usage of some of the resources that it has been allocated. (To determine whether this has occurred, the parent must have a mechanism to inspect the state of its children.)

• The task assigned to the child is no longer required.

• The parent is exiting, and the operating system does not allow a child to continue if its parent terminates.

Some systems do not allow a child to exist if its parent has terminated. In such systems, if a process terminates (either normally or abnormally), then all its children must also be terminated. This phenomenon, referred to as cascading termination, is normally initiated by the operating system.

To illustrate process execution and termination, consider that, in Linux and UNIX systems, we can terminate a process by using the exit() system call, providing an exit status as a parameter:

/* exit with status 1 */ exit(1);

In fact, under normal termination, exit() will be called either directly (as shown above) or indirectly, as the C run-time library (which is added to UNIX executable files) will include a call to exit() by default.

A parent process may wait for the termination of a child process by using the wait() system call. The wait() system call is passed a parameter that allows the parent to obtain the exit status of the child. This system call also returns the process identifier of the terminated child so that the parent can tell which of its children has terminated:

pid t pid; int status;

pid = wait(&status);

When a process terminates, its resources are deallocated by the operating system. However, its entry in the process table must remain there until the parent calls wait(), because the process table contains the process’s exit status. A process that has terminated, but whose parent has not yet called wait(), is known as a zombie process. All processes transition to this state when they terminate, but generally they exist as zombies only briefly. Once the parent calls wait(), the process identifier of the zombie process and its entry in the process table are released.

Now consider what would happen if a parent did not invoke wait() and instead terminated, thereby leaving its child processes as orphans. Traditional UNIX systems addressed this scenario by assigning the init process as the new parent to orphan processes. (Recall from Section 3.3.1 that init serves as the root of the process hierarchy in UNIX systems.) The init process periodically invokes wait(), thereby allowing the exit status of any orphaned process to be collected and releasing the orphan’s process identifier and process-table entry.

Althoughmost Linux systems have replaced initwith systemd, the latter process can still serve the same role, although Linux also allows processes other than systemd to inherit orphan processes and manage their termination.

Android Process Hierarchy

Because of resource constraints such as limited memory, mobile operating systems may have to terminate existing processes to reclaim limited system resources. Rather than terminating an arbitrary process, Android has identified an importance hierarchy of processes, and when the system must terminate a process to make resources available for a new, or more important, process, it terminates processes in order of increasing importance. From most to least important, the hierarchy of process classifications is as follows:

• Foreground process—The current process visible on the screen, represent- ing the application the user is currently interacting with

• Visible process—A process that is not directly visible on the foreground but that is performing an activity that the foreground process is referring to (that is, a process performing an activity whose status is displayed on the foreground process)

• Service process—A process that is similar to a background process but is performing an activity that is apparent to the user (such as streaming music)

• Background process—A process that may be performing an activity but is not apparent to the user.

• Empty process—A process that holds no active components associated with any application

If system resources must be reclaimed, Android will first terminate empty processes, followed by background processes, and so forth. Processes are assigned an importance ranking, and Android attempts to assign a process as high a ranking as possible. For example, if a process is providing a service and is also visible, it will be assigned the more-important visible classification.

Furthermore, Android development practices suggest following the guide- lines of the process life cycle. When these guidelines are followed, the state of a process will be saved prior to termination and resumed at its saved state if the user navigates back to the application.