IPC in Message-Passing Systems

In Section 3.5, we showed how cooperating processes can communicate in a shared-memory environment. The scheme requires that these processes share a region of memory and that the code for accessing andmanipulating the shared memory be written explicitly by the application programmer. Another way to achieve the same effect is for the operating system to provide the means for cooperating processes to communicate with each other via a message-passing facility.

Message passingprovides amechanism to allowprocesses to communicate and to synchronize their actions without sharing the same address space. It is particularly useful in a distributed environment, where the communicating processes may reside on different computers connected by a network. For example, an Internet chat program could be designed so that chat participants communicate with one another by exchanging messages.

Amessage-passing facility provides at least two operations:

send(message) and

receive(message)

Messages sent by a process can be either fixed or variable in size. If only fixed-sized messages can be sent, the system-level implementation is straight- forward. This restriction, however, makes the task of programming more diffi- cult. Conversely, variable-sizedmessages require amore complex system-level implementation, but the programming task becomes simpler. This is a common kind of tradeoff seen throughout operating-system design.

If processes_P_ and_Q_want to communicate, theymust sendmessages to and receive messages from each other: a communication link must exist between them. This link can be implemented in a variety ofways.We are concerned here notwith the link’s physical implementation (such as sharedmemory, hardware bus, or network, which are covered in Chapter 19) but rather with its logical implementation. Here are several methods for logically implementing a link and the send()/receive() operations:

• Direct or indirect communication

• Synchronous or asynchronous communication

• Automatic or explicit buffering

We look at issues related to each of these features next.

Naming

Processes that want to communicate must have a way to refer to each other. They can use either direct or indirect communication.

Under direct communication, each process that wants to communicate must explicitly name the recipient or sender of the communication. In this scheme, the send() and receive() primitives are defined as:

• send(P, message)—Send a message to process P.

• receive(Q, message)—Receive a message from process Q.

A communication link in this scheme has the following properties:

• A link is established automatically between every pair of processes that want to communicate. The processes need to know only each other’s identity to communicate.

• A link is associated with exactly two processes.

• Between each pair of processes, there exists exactly one link.

This scheme exhibits symmetry in addressing; that is, both the sender pro- cess and the receiver process must name the other to communicate. A variant of this scheme employs asymmetry in addressing. Here, only the sender names the recipient; the recipient is not required to name the sender. In this scheme, the send() and receive() primitives are defined as follows:

• send(P, message)—Send a message to process P.

• receive(id, message)—Receive a message from any process. The vari- able id is set to the name of the process with which communication has taken place.

The disadvantage in both of these schemes (symmetric and asymmetric) is the limited modularity of the resulting process definitions. Changing the identifier of a process may necessitate examining all other process definitions. All references to the old identifier must be found, so that they can be modified to the new identifier. In general, any such hard-coding techniques, where iden- tifiers must be explicitly stated, are less desirable than techniques involving indirection, as described next.

With indirect communication, the messages are sent to and received from mailboxes, or ports. A mailbox can be viewed abstractly as an object into which messages can be placed by processes and from which messages can be removed. Each mailbox has a unique identification. For example, POSIX message queues use an integer value to identify a mailbox. Aprocess can com- municate with another process via a number of different mailboxes, but two processes can communicate only if they have a shared mailbox. The send() and receive() primitives are defined as follows:

• send(A, message)—Send a message to mailbox A.

• receive(A, message)—Receive a message from mailbox A.

In this scheme, a communication link has the following properties:

• A link is established between a pair of processes only if both members of the pair have a shared mailbox.

• A link may be associated with more than two processes.

• Between each pair of communicating processes, a number of different links may exist, with each link corresponding to one mailbox.

Now suppose that processes _P_1, _P_2, and _P_3 all share mailbox A. Process P_1 sends amessage to_A, while both P_2 and_P_3 execute a receive() from_A.Which process will receive the message sent by _P_1? The answer depends on which of the following methods we choose:

• Allow a link to be associated with two processes at most.

• Allow at most one process at a time to execute a receive() operation.

• Allow the system to select arbitrarily which process will receive the mes- sage (that is, either _P_2 or _P_3, but not both, will receive the message). The system may define an algorithm for selecting which process will receive the message (for example, **round robin,**where processes take turns receiv- ing messages). The system may identify the receiver to the sender.

A mailbox may be owned either by a process or by the operating system. If the mailbox is owned by a process (that is, the mailbox is part of the address space of the process), then we distinguish between the owner (which can only receive messages through this mailbox) and the user (which can only send messages to the mailbox). Since each mailbox has a unique owner, there can be no confusion about which process should receive a message sent to this mailbox. When a process that owns a mailbox terminates, the mailbox disappears. Any process that subsequently sends a message to this mailbox must be notified that the mailbox no longer exists.

In contrast, a mailbox that is owned by the operating system has an exis- tence of its own. It is independent and is not attached to any particular process. The operating system then must provide a mechanism that allows a process to do the following:

• Create a new mailbox.

• Send and receive messages through the mailbox.

• Delete a mailbox.

The process that creates a new mailbox is that mailbox’s owner by default. Initially, the owner is the only process that can receive messages through this mailbox. However, the ownership and receiving privilege may be passed to other processes through appropriate system calls. Of course, this provision could result in multiple receivers for each mailbox.

Synchronization

Communication between processes takes place through calls to send() and receive() primitives. There are different design options for implementing each primitive. Message passing may be either blocking or nonblocking— also known as synchronous and asynchronous. (Throughout this text, youwill encounter the concepts of synchronous and asynchronous behavior in relation to various operating-system algorithms.)

• Blocking send. The sending process is blocked until the message is received by the receiving process or by the mailbox.

• Nonblocking send. The sending process sends the message and resumes operation.

• Blocking receive. The receiver blocks until a message is available.

• Nonblocking receive. The receiver retrieves either a valid message or a null.

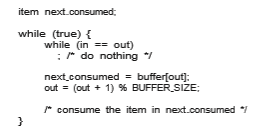

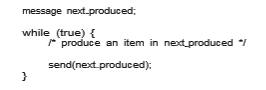

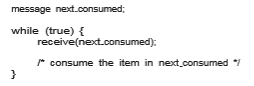

Different combinations of send() and receive() are possible. When both send() and receive() are blocking, we have a rendezvous between the sender and the receiver. The solution to the producer–consumer problem becomes trivial when we use blocking send() and receive() statements. The producer merely invokes the blocking send() call and waits until the message is delivered to either the receiver or the mailbox. Likewise, when the consumer invokes receive(), it blocks until a message is available. This is illustrated in Figures 3.14 and 3.15.

Buffering

Whether communication is direct or indirect, messages exchanged by commu- nicating processes reside in a temporary queue. Basically, such queues can be implemented in three ways:

• Zero capacity. The queue has a maximum length of zero; thus, the link cannot have any messages waiting in it. In this case, the sender must block until the recipient receives the message.

• Bounded capacity. The queue has finite length n; thus, at most _n_messages can reside in it. If the queue is not full when a new message is sent, the message is placed in the queue (either the message is copied or a pointer to the message is kept), and the sender can continue execution without

waiting. The link’s capacity is finite, however. If the link is full, the sender must block until space is available in the queue.

• Unbounded capacity. The queue’s length is potentially infinite; thus, any number of messages can wait in it. The sender never blocks.

The zero-capacity case is sometimes referred to as a message system with no buffering. The other cases are referred to as systems with automatic buffering.