Interprocess Communication

Processes executing concurrently in the operating system may be either inde- pendent processes or cooperating processes. Aprocess is independent if it does not share data with any other processes executing in the system. A process is cooperating if it can affect or be affected by the other processes executing in the system. Clearly, any process that shares data with other processes is a cooperating process.

There are several reasons for providing an environment that allows process cooperation:

• Information sharing. Since several applications may be interested in the same piece of information (for instance, copying and pasting), we must provide an environment to allow concurrent access to such information.

• Computation speedup. If we want a particular task to run faster, we must break it into subtasks, each of which will be executing in parallel with the others. Notice that such a speedup can be achieved only if the computer has multiple processing cores.

• Modularity. We may want to construct the system in a modular fashion, dividing the system functions into separate processes or threads, as we discussed in Chapter 2.

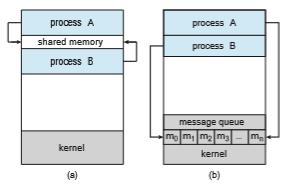

Cooperating processes require an interprocess communication (IPC) mechanism that will allow them to exchange data— that is, send data to and receive data from each other. There are two fundamental models of interprocess communication: shared memory and message passing. In the shared-memory model, a region of memory that is shared by the cooperating processes is established. Processes can then exchange information by reading and writing data to the shared region. In the message-passing model,

MULTIPROCESS ARCHITECTURE—CHROME BROWSER

Many websites contain active content, such as JavaScript, Flash, and HTML5 to provide a rich and dynamic web-browsing experience. Unfortunately, these web applications may also contain software bugs, which can result in sluggish response times and can even cause the web browser to crash. This isn’t a big problem in aweb browser that displays content from only oneweb- site. But most contemporary web browsers provide tabbed browsing, which allows a single instance of aweb browser application to open severalwebsites at the same time, with each site in a separate tab. To switch between the dif- ferent sites, a user need only click on the appropriate tab. This arrangement is illustrated below:

Google’s Chrome web browser was designed to address this issue by using a multiprocess architecture. Chrome identifies three different types of processes: browser, renderers, and plug-ins.

• The browser process is responsible for managing the user interface as well as disk and network I/O. A new browser process is created when Chrome is started. Only one browser process is created.

• Renderer processes contain logic for rendering web pages. Thus, they contain the logic for handling HTML, Javascript, images, and so forth. As a general rule, a new renderer process is created for each website opened in a new tab, and so several renderer processes may be active at the same time.

• A plug-in process is created for each type of plug-in (such as Flash or QuickTime) in use. Plug-in processes contain the code for the plug-in as well as additional code that enables the plug-in to communicate with associated renderer processes and the browser process.

The advantage of the multiprocess approach is that websites run in iso- lation from one another. If one website crashes, only its renderer process is affected; all other processes remain unharmed. Furthermore, renderer pro- cesses run in a sandbox, which means that access to disk and network I/O is restricted, minimizing the effects of any security exploits.

communication takes place by means of messages exchanged between the cooperating processes. The two communications models are contrasted in Figure 3.11.

Both of the models just mentioned are common in operating systems, and many systems implement both. Message passing is useful for exchanging smaller amounts of data, because no conflicts need be avoided. Message pass- ing is also easier to implement in a distributed system than shared memory. (Although there are systems that provide distributed shared memory, we do not consider them in this text.) Sharedmemory can be faster thanmessagepass- ing, since message-passing systems are typically implemented using system calls and thus require the more time-consuming task of kernel intervention. In shared-memory systems, system calls are required only to establish shared- memory regions. Once shared memory is established, all accesses are treated as routine memory accesses, and no assistance from the kernel is required.

In Section 3.5 and Section 3.6 we explore shared-memory and message- passing systems in more detail.