Background

We’ve already seen that processes can execute concurrently or in parallel. Sec- tion 3.2.2 introduced the role of process scheduling and described how the CPU scheduler switches rapidly between processes to provide concurrent exe- cution. This means that one process may only partially complete execution before another process is scheduled. In fact, a process may be interrupted at any point in its instruction stream, and the processing core may be assigned to execute instructions of another process. Additionally, Section 4.2 introduced parallel execution, in which two instruction streams (representing different processes) execute simultaneously on separate processing cores. In this chap- ter, we explain how concurrent or parallel execution can contribute to issues involving the integrity of data shared by several processes.

Let’s consider an example of how this can happen. In Chapter 3, we devel- oped a model of a system consisting of cooperating sequential processes or threads, all running asynchronously and possibly sharing data. We illustrated this model with the producer–consumer problem, which is a representative paradigm of many operating system functions. Specifically, in Section 3.5, we described how a bounded buffer could be used to enable processes to share memory.

We now return to our consideration of the bounded buffer. As we pointed out, our original solution allowed at most BUFFER SIZE − 1 items in the buffer at the same time. Suppose we want to modify the algorithm to remedy this deficiency. One possibility is to add an integer variable, count, initialized to 0. count is incremented every time we add a new item to the buffer and is decremented every time we remove one item from the buffer. The code for the producer process can be modified as follows:

while (true) {*/ *produce an item in next produced */

while (count == BUFFER SIZE) ;*/ *do nothing */

buffer[in] = next produced; in = (in + 1) % BUFFER SIZE; count++;

}

The code for the consumer process can be modified as follows:

while (true) { while (count == 0)

;*/ *do nothing */

next consumed = buffer[out]; out = (out + 1) % BUFFER SIZE; count--;

/* consume the item in next consumed */ }

Although the producer and consumer routines shown above are correct separately, they may not function correctly when executed concurrently. As an illustration, suppose that the value of the variable count is currently 5 and that the producer and consumer processes concurrently execute the statements “count++” and “count–”. Following the execution of these two statements, the value of the variable countmay be 4, 5, or 6! The only correct result, though, is count == 5, which is generated correctly if the producer and consumer execute separately.

We can show that the value of count may be incorrect as follows. Note that the statement “count++” may be implemented in machine language (on a typical machine) as follows:

register 1 = count register 1 = register 1 + 1 count = register 1

where _register_1 is one of the local CPU registers. Similarly, the statement “count- -” is implemented as follows:

register 2 = count register 2 = register 2 − 1 count = register 2

where again _register_2 is one of the local CPU registers. Even though _register_1 and _register_2 may be the same physical register, remember that the contents of this register will be saved and restored by the interrupt handler (Section 1.2.3).

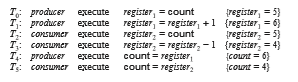

The concurrent execution of “count++” and “count–” is equivalent to a sequential execution in which the lower-level statements presented previously are interleaved in some arbitrary order (but the order within each high-level statement is preserved). One such interleaving is the following:

We would arrive at this incorrect state because we allowed both processes to manipulate the variable count concurrently. A situation like this, where several processes access and manipulate the same data concurrently and the outcome of the execution depends on the particular order in which the access takes place, is called a race condition. To guard against the race condition above, we need to ensure that only one process at a time can be manipulating the variable count. To make such a guarantee, we require that the processes be synchronized in some way.

Situations such as the one just described occur frequently in operating systems as different parts of the system manipulate resources. Furthermore, as we have emphasized in earlier chapters, the prominence of multicore sys- tems has brought an increased emphasis on developing multithreaded appli- cations. In such applications, several threads—which are quite possibly shar- ing data—are running in parallel on different processing cores. Clearly, we want any changes that result from such activities not to interfere with one another. Because of the importance of this issue, we devote a major portion of this chapter to process synchronization and coordination among cooperating processes.