Synchronization in Java

The Java language and its API have provided rich support for thread syn- chronization since the origins of the language. In this section, we first cover Javamonitors, Java’s original synchronizationmechanism.We then cover three additional mechanisms that were introduced in Release 1.5: reentrant locks, semaphores, and condition variables. We include these because they represent the most common locking and synchronization mechanisms. However, the Java API provides many features that we do not cover in this text—for exam- ple, support for atomic variables and the CAS instruction—and we encourage interested readers to consult the bibliography for more information.

Java Monitors

Java provides a monitor-like concurrency mechanism for thread synchroniza- tion. We illustrate this mechanism with the BoundedBuffer class (Figure 7.9), which implements a solution to the bounded-buffer problem wherein the pro- ducer and consumer invoke the insert() and remove() methods, respec- tively.

Every object in Java has associated with it a single lock. When a method is declared to be synchronized, calling the method requires owning the lock for the object. We declare a synchronizedmethod by placing the synchronized keyword in the method definition, such as with the insert() and remove() methods in the BoundedBuffer class.

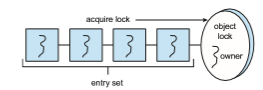

Invoking a synchronized method requires owning the lock on an object instance of Bounded Buffer. If the lock is already owned by another thread, the thread calling the synchronizedmethod blocks and is placed in the entry set for the object’s lock. The entry set represents the set of threads waiting for the lock to become available. If the lock is available when a synchronized method is called, the calling thread becomes the owner of the object’s lock and can enter the method. The lock is released when the thread exits the method. If the entry set for the lock is not empty when the lock is released, the JVM

public class BoundedBuffer<E> {

private static final int BUFFER SIZE = 5;

private int count, in, out; private E[] buffer;

public BoundedBuffer() { count = 0; in = 0; out = 0; buffer = (E[]) new Object[BUFFER SIZE];

}

/* Producers call this method */ public **synchronized** void insert(E item) {

/* See Figure 7.11 */ }

/* Consumers call this method */ public **synchronized** E remove() {

/* See Figure 7.11 */ }

}

Figure 7.9 Bounded buffer using Java synchronization.

arbitrarily selects a thread from this set to be the owner of the lock. (When we say “arbitrarily,”wemean that the specification does not require that threads in this set be organized in any particular order. However, in practice, most virtual machines order threads in the entry set according to a FIFO policy.) Figure 7.10 illustrates how the entry set operates.

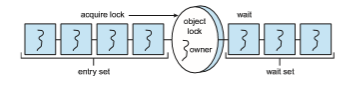

In addition to having a lock, every object also has associated with it a wait set consisting of a set of threads. This wait set is initially empty. When a thread enters a synchronizedmethod, it owns the lock for the object. However, this thread may determine that it is unable to continue because a certain condition

BLOCK SYNCHRONIZATION

The amount of time between when a lock is acquired and when it is released is defined as the scope of the lock. A synchronized method that has only a small percentage of its code manipulating shared data may yield a scope that is too large. In such an instance, it may be better to synchronize only the block of code that manipulates shared data than to synchronize the entire method. Such a design results in a smaller lock scope. Thus, in addition to declaring synchronized methods, Java also allows block synchronization, as illustrated below. Only the access to the critical-section code requires ownership of the object lock for the this object.

public void someMethod() {*/ *non-critical section */

synchronized(this) {*/ *critical section */

}

/* remainder section */ }

has not been met. That will happen, for example, if the producer calls the insert() method and the buffer is full. The thread then will release the lock and wait until the condition that will allow it to continue is met.

When a thread calls the wait()method, the following happens:

1. The thread releases the lock for the object.

2. The state of the thread is set to blocked.

3. The thread is placed in the wait set for the object.

Consider the example in Figure 7.11. If the producer calls the insert() method and sees that the buffer is full, it calls the wait() method. This call releases the lock, blocks the producer, and puts the producer in the wait set for the object. Because the producer has released the lock, the consumer ultimately enters the remove()method,where it frees space in the buffer for the producer. Figure 7.12 illustrates the entry and wait sets for a lock. (Note that although wait() can throw an InterruptedException, we choose to ignore it for code clarity and simplicity.)

How does the consumer thread signal that the producermay nowproceed? Ordinarily, when a thread exits a synchronizedmethod, the departing thread releases only the lock associated with the object, possibly removing a thread from the entry set and giving it ownership of the lock. However, at the end of the insert() and remove()methods, we have a call to the method notify(). The call to notify():

1. Picks an arbitrary thread T from the list of threads in the wait set

/* Producers call this method */ public **synchronized** void insert(E item) {

while (count == BUFFER SIZE) { try {

**wait();** } catch (InterruptedException ie) _{ }_

}

buffer[in] = item; in = (in + 1) % BUFFER SIZE; count++;

**notify();** }

/* Consumers call this method */ public **synchronized** E remove() {

E item;

while (count == 0) { try {

**wait();** } catch (InterruptedException ie) { }

}

item = buffer[out]; out = (out + 1) % BUFFER SIZE; count--;

**notify();**

return item; }

Figure 7.11 insert() and remove() methods using wait() and notify().

2. Moves T from the wait set to the entry set

3. Sets the state of T from blocked to runnable

T is now eligible to compete for the lock with the other threads. Once T has regained control of the lock, it returns from calling wait(), where it may check the value of count again. (Again, the selection of an arbitrary thread is according to the Java specification; in practice, most Java virtual machines order threads in the wait set according to a FIFO policy.)

Next, we describe the wait() and notify() methods in terms of the methods shown in Figure 7.11. We assume that the buffer is full and the lock for the object is available.

• The producer calls the insert() method, sees that the lock is available, and enters the method. Once in the method, the producer determines that the buffer is full and calls wait(). The call to wait() releases the lock for the object, sets the state of the producer to blocked, and puts the producer in the wait set for the object.

• The consumer ultimately calls and enters the remove() method, as the lock for the object is now available. The consumer removes an item from the buffer and calls notify(). Note that the consumer still owns the lock for the object.

• The call to notify() removes the producer from the wait set for the object, moves the producer to the entry set, and sets the producer’s state to runnable.

• The consumer exits the remove()method. Exiting thismethod releases the lock for the object.

• The producer tries to reacquire the lock and is successful. It resumes execu- tion from the call to wait(). The producer tests the while loop, determines that room is available in the buffer, and proceedswith the remainder of the insert() method. If no thread is in the wait set for the object, the call to notify() is ignored. When the producer exits the method, it releases the lock for the object.

The synchronized, wait(), and notify()mechanisms have been part of Java since its origins. However, later revisions of the Java API introducedmuch more flexible and robust locking mechanisms, some of which we examine in the following sections.

Reentrant Locks

Perhaps the simplest lockingmechanism available in the API is the Reentrant- Lock. In many ways, a ReentrantLock acts like the synchronized statement described in Section 7.4.1: a ReentrantLock is owned by a single thread and is used to provide mutually exclusive access to a shared resource. However, the ReentrantLock provides several additional features, such as setting a fairness parameter,which favors granting the lock to the longest-waiting thread. (Recall

that the specification for the JVM does not indicate that threads in the wait set for an object lock are to be ordered in any specific fashion.)

A thread acquires a ReentrantLock lock by invoking its lock() method. If the lock is available—or if the thread invoking lock() already owns it, which is why it is termed reentrant—lock() assigns the invoking thread lock ownership and returns control. If the lock is unavailable, the invoking thread blocks until it is ultimately assigned the lock when its owner invokes unlock().ReentrantLock implements the Lock interface; it is used as follows:

Lock key = new ReentrantLock();

key.**lock**(); try {

/* critical section */ } finally {

key.**unlock**(); }

The programming idiom of using try and finally requires a bit of expla- nation. If the lock is acquired via the lock() method, it is important that the lock be similarly released. By enclosing unlock() in a finally clause, we ensure that the lock is released once the critical section completes or if an excep- tion occurs within the try block. Notice that we do not place the call to lock() within the try clause, as lock() does not throw any checked exceptions. Con- siderwhat happens ifwe place lock()within the try clause and an unchecked exception occurs when lock() is invoked (such as OutofMemoryError): The finally clause triggers the call tounlock(), which then throws the unchecked IllegalMonitorStateException, as the lockwas never acquired. This Ille- galMonitorStateException replaces the unchecked exception that occurred when lock() was invoked, thereby obscuring the reason why the program initially failed.

Whereas a ReentrantLock provides mutual exclusion, it may be too con- servative a strategy if multiple threads only read, but do not write, shared data. (We described this scenario in Section 7.1.2.) To address this need, the Java API also provides a ReentrantReadWriteLock, which is a lock that allows multiple concurrent readers but only one writer.

Semaphores

The Java API also provides a counting semaphore, as described in Section 6.6. The constructor for the semaphore appears as

Semaphore(int value);

where value specifies the initial value of the semaphore (a negative value is allowed). The acquire() method throws an InterruptedException if the acquiring thread is interrupted. The following example illustrates using a semaphore for mutual exclusion:

Semaphore sem = new Semaphore(1);

try { sem.**acquire**();*/ *critical section */

} catch (InterruptedException ie) _{ }_ finally {

sem.**release**(); }

Notice that we place the call to release() in the finally clause to ensure that the semaphore is released.

Condition Variables

The last utility we cover in the Java API is the condition variable. Just as the ReentrantLock is similar to Java’s synchronized statement, condition variables provide functionality similar to the wait() and notify()methods. Therefore, to providemutual exclusion, a condition variablemust be associated with a reentrant lock.

We create a condition variable by first creating a ReentrantLock and invoking its newCondition()method, which returns a Condition object rep- resenting the condition variable for the associated ReentrantLock. This is illustrated in the following statements:

Lock key = new ReentrantLock();

Condition condVar = key.newCondition();

Once the condition variable has been obtained, we can invoke its await() and signal() methods, which function in the same way as the wait() and signal() commands described in Section 6.7.

Recall that with monitors as described in Section 6.7, the wait() and signal() operations can be applied to named condition variables, allowing a thread towait for a specific condition or to be notifiedwhen a specific condition has been met. At the language level, Java does not provide support for named condition variables. Each Java monitor is associated with just one unnamed condition variable, and the wait() and notify() operations described in Section 7.4.1 apply only to this single condition variable. When a Java thread is awakened via notify(), it receives no information as towhy it was awakened; it is up to the reactivated thread to check for itself whether the condition for which it was waiting has been met. Condition variables remedy this by allowing a specific thread to be notified.

We illustrate with the following example: Suppose we have five threads, numbered 0 through 4, and a shared variable turn indicating which thread’s turn it is. When a thread wishes to do work, it calls the doWork() method in Figure 7.13, passing its thread number. Only the thread whose value of threadNumbermatches the value of turn can proceed; other threadsmustwait their turn.

/* threadNumber is the thread that wishes to do some work */ public void doWork(int threadNumber) {

lock.lock();

try {*/ ** * If it’s not my turn, then wait * until I’m signaled. */

if (threadNumber != turn) condVars[threadNumber].**await();**

/** * Do some work for awhile ... */

/** * Now signal to the next thread. */

turn = (turn + 1) % 5; condVars[turn].**signal();**

} catch (InterruptedException ie) _{ }_ finally {

lock.unlock(); }

}

Figure 7.13 Example using Java condition variables.

We also must create a ReentrantLock and five condition variables (repre- senting the conditions the threads are waiting for) to signal the thread whose turn is next. This is shown below:

Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

Condition[] condVars = new Condition[5];

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) condVars[i] = lock.newCondition();

When a thread enters doWork(), it invokes the await() method on its associated condition variable if its threadNumber is not equal to turn, only to resume when it is signaled by another thread. After a thread has completed itswork, it signals the condition variable associatedwith the threadwhose turn follows.

It is important to note that doWork() does not need to be declared syn- chronized, as the ReentrantLock provides mutual exclusion. When a thread invokes await() on the condition variable, it releases the associated Reen- trantLock, allowing another thread to acquire the mutual exclusion lock. Similarly, when signal() is invoked, only the condition variable is signaled; the lock is released by invoking unlock().