User and Operating-System Interface

We mentioned earlier that there are several ways for users to interface with the operating system. Here, we discuss three fundamental approaches. One provides a command-line interface, or command interpreter, that allows users to directly enter commands to be performedby the operating system. The other two allow users to interface with the operating system via a graphical user interface, or GUI.

Command Interpreters

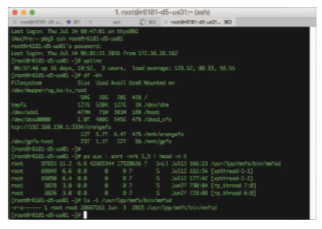

Most operating systems, including Linux, UNIX, and Windows, treat the com- mand interpreter as a special program that is running when a process is ini- tiated or when a user first logs on (on interactive systems). On systems with multiple command interpreters to choose from, the interpreters are known as shells. For example, onUNIX andLinux systems, a usermay choose among sev- eral different shells, including the C shell, Bourne-Again shell, Korn shell, and others. Third-party shells and free user-written shells are also available. Most shells provide similar functionality, and a user’s choice of which shell to use is generally based on personal preference. Figure 2.2 shows the Bourne-Again (or bash) shell command interpreter being used on macOS.

Themain function of the command interpreter is to get and execute the next user-specified command. Many of the commands given at this level manipu- late files: create, delete, list, print, copy, execute, and so on. The various shells available on UNIX systems operate in this way. These commands can be imple- mented in two general ways.

In one approach, the command interpreter itself contains the code to exe- cute the command. For example, a command to delete a file may cause the command interpreter to jump to a section of its code that sets up the parameters and makes the appropriate system call. In this case, the number of commands that can be given determines the size of the command interpreter, since each command requires its own implementing code.

An alternative approach—used by UNIX, among other operating systems —implements most commands through system programs. In this case, the command interpreter does not understand the command in any way; it merely uses the command to identify a file to be loaded into memory and executed. Thus, the UNIX command to delete a file

defined completely by the code in the file rm. In this way, programmers can add new commands to the system easily by creating new files with the proper program logic. The command-interpreter program, which can be small, does not have to be changed for new commands to be added.

Graphical User Interface

A second strategy for interfacing with the operating system is through a user- friendly graphical user interface, or GUI. Here, rather than entering commands directly via a command-line interface, users employ a mouse-based window- and-menu system characterized by a desktop metaphor. The user moves the mouse to position its pointer on images, or icons, on the screen (the desktop) that represent programs, files, directories, and system functions. Depending on the mouse pointer’s location, clicking a button on the mouse can invoke a program, select a file or directory—known as a folder—or pull down a menu that contains commands.

Graphical user interfaces first appeared due in part to research taking place in the early 1970s at Xerox PARC research facility. The first GUI appeared on the Xerox Alto computer in 1973. However, graphical interfaces became more widespread with the advent of Apple Macintosh computers in the 1980s. The user interface for the Macintosh operating system has undergone various changes over the years, the most significant being the adoption of the Aqua interface that appeared with macOS. Microsoft’s first version of Windows— Version 1.0—was based on the addition of a GUI interface to the MS-DOS operating system. Later versions ofWindows havemade significant changes in the appearance of the GUI along with several enhancements in its functionality.

Traditionally, UNIX systems have been dominated by command-line inter- faces. Various GUI interfaces are available, however, with significant develop- ment in GUI designs from various open-source projects, such as K Desktop Environment (or KDE) and the GNOME desktop by the GNU project. Both the KDE and GNOME desktops run on Linux and various UNIX systems and are available under open-source licenses, which means their source code is readily available for reading and for modification under specific license terms.

Touch-Screen Interface

Because a either a command-line interface or a mouse-and-keyboard system is impractical for most mobile systems, smartphones and handheld tablet com- puters typically use a touch-screen interface. Here, users interact by making gestures on the touch screen—for example, pressing and swiping fingers across the screen. Although earlier smartphones included a physical keyboard, most smartphones and tablets now simulate a keyboard on the touch screen. Figure 2.3 illustrates the touch screen of the Apple iPhone. Both the iPad and the iPhone use the Springboard touch-screen interface.

Choice of Interface

The choice of whether to use a command-line or GUI interface is mostly one of personal preference. System administrators who manage computers and power users who have deep knowledge of a system frequently use the

command-line interface. For them, it is more efficient, giving them faster access to the activities they need to perform. Indeed, on some systems, only a subset of system functions is available via the GUI, leaving the less common tasks to those who are command-line knowledgeable. Further, command-line inter- faces usually make repetitive tasks easier, in part because they have their own programmability. For example, if a frequent task requires a set of command- line steps, those steps can be recorded into a file, and that file can be run just like a program. The program is not compiled into executable code but rather is interpreted by the command-line interface. These shell scripts are very common on systems that are command-line oriented, such as UNIX and Linux.

In contrast, most Windows users are happy to use the Windows GUI envi- ronment and almost never use the shell interface. Recent versions of the Win- dows operating system provide both a standard GUI for desktop and tradi- tional laptops and a touch screen for tablets. The various changes undergone by the Macintosh operating systems also provide a nice study in contrast. His- torically, Mac OS has not provided a command-line interface, always requiring its users to interfacewith the operating systemusing its GUI. However,with the release of macOS (which is in part implemented using a UNIX kernel), the oper- ating system now provides both an Aqua GUI and a command-line interface. Figure 2.4 is a screenshot of the macOS GUI.

Although there are apps that provide a command-line interface for iOS and Android mobile systems, they are rarely used. Instead, almost all users of mobile systems interact with their devices using the touch-screen interface.

The user interface can vary from system to system and even from user to user within a system; however, it typically is substantially removed from the actual system structure. The design of a useful and intuitive user interface is therefore not a direct function of the operating system. In this book, we concentrate on the fundamental problems of providing adequate service to

user programs. From the point of view of the operating system, we do not distinguish between user programs and system programs.