Allocation of Frames

We turn next to the issue of allocation. How dowe allocate the fixed amount of free memory among the various processes? If we have 93 free frames and two processes, how many frames does each process get?

Consider a simple case of a system with 128 frames. The operating system may take 35, leaving 93 frames for the user process. Under pure demand paging, all 93 frames would initially be put on the free-frame list. When a user process started execution, it would generate a sequence of page faults. The first 93 page faults would all get free frames from the free-frame list. When the free-frame list was exhausted, a page-replacement algorithm would be used to select one of the 93 in-memory pages to be replaced with the 94th, and so on. When the process terminated, the 93 frames would once again be placed on the free-frame list.

There are many variations on this simple strategy. We can require that the operating system allocate all its buffer and table space from the free-frame list. When this space is not in use by the operating system, it can be used to support user paging.We can try to keep three free frames reserved on the free-frame list at all times. Thus, when a page fault occurs, there is a free frame available to page into. While the page swap is taking place, a replacement can be selected, which is then written to the storage device as the user process continues to execute. Other variants are also possible, but the basic strategy is clear: the user process is allocated any free frame.

Minimum Number of Frames

Our strategies for the allocation of frames are constrained in various ways. We cannot, for example, allocate more than the total number of available frames (unless there is page sharing). Wemust also allocate at least a minimum number of frames. Here, we look more closely at the latter requirement.

One reason for allocating at least a minimum number of frames involves performance. Obviously, as the number of frames allocated to each process decreases, the page-fault rate increases, slowing process execution. In addi- tion, remember that, when a page fault occurs before an executing instruction is complete, the instruction must be restarted. Consequently, we must have enough frames to hold all the different pages that any single instruction can reference.

For example, consider a machine in which all memory-reference instruc- tionsmay reference only onememory address. In this case, we need at least one frame for the instruction and one frame for the memory reference. In addition, if one-level indirect addressing is allowed (for example, a load instruction on frame 16 can refer to an address on frame 0, which is an indirect reference to frame 23), then paging requires at least three frames per process. (Think about what might happen if a process had only two frames.)

The minimum number of frames is defined by the computer architecture. For example, if the move instruction for a given architecture includes more than one word for some addressing modes, the instruction itself may straddle two frames. In addition, if each of its two operands may be indirect references, a total of six frames are required. As another example, the move instruction for Intel 32- and 64-bit architectures allows data to move only from register to register and between registers and memory; it does not allow direct memory- to-memory movement, thereby limiting the required minimum number of frames for a process.

Whereas the minimum number of frames per process is defined by the architecture, the maximum number is defined by the amount of available physical memory. In between, we are still left with significant choice in frame allocation.

Allocation Algorithms

The easiest way to split m frames among n processes is to give everyone an equal share, m/n frames (ignoring frames needed by the operating system for the moment). For instance, if there are 93 frames and 5 processes, each process will get 18 frames. The 3 leftover frames can be used as a free-frame buffer pool. This scheme is called equal allocation.

An alternative is to recognize that various processes will need differing amounts of memory. Consider a system with a 1-KB frame size. If a small student process of 10 KB and an interactive database of 127 KB are the only two processes running in a system with 62 free frames, it does not make much sense to give each process 31 frames. The student process does not need more than 10 frames, so the other 21 are, strictly speaking, wasted.

To solve this problem, we can use proportional allocation, in which we allocate available memory to each process according to its size. Let the size of the virtual memory for process pi be si, and define

S = ∑ si.

Then, if the total number of available frames is m, we allocate ai frames to process pi, where ai is approximately

ai = si/S × m.

Of course, we must adjust each ai to be an integer that is greater than the minimum number of frames required by the instruction set, with a sum not exceeding m.

With proportional allocation, we would split 62 frames between two pro- cesses, one of 10 pages and one of 127 pages, by allocating 4 frames and 57 frames, respectively, since

10/137 × 62 ≈ 4 and 127/137 × 62 ≈ 57.

In this way, both processes share the available frames according to their “needs,” rather than equally.

In both equal and proportional allocation, of course, the allocation may vary according to the multiprogramming level. If the multiprogramming level is increased, each processwill lose some frames to provide thememory needed for the new process. Conversely, if the multiprogramming level decreases, the frames that were allocated to the departed process can be spread over the remaining processes.

Notice that, with either equal or proportional allocation, a high-priority process is treated the same as a low-priority process. By its definition, however, we may want to give the high-priority process more memory to speed its execution, to the detriment of low-priority processes. One solution is to use a proportional allocation scheme wherein the ratio of frames depends not on the relative sizes of processes but rather on the priorities of processes or on a combination of size and priority.

Global versus Local Allocation

Another important factor in the way frames are allocated to the various pro- cesses is page replacement. With multiple processes competing for frames, we can classify page-replacement algorithms into two broad categories: global replacement and local replacement. Global replacement allows a process to select a replacement frame from the set of all frames, even if that frame is currently allocated to some other process; that is, one process can take a frame from another. Local replacement requires that each process select from only its own set of allocated frames.

For example, consider an allocation scheme wherein we allow high- priority processes to select frames from low-priority processes for replacement. A process can select a replacement from among its own frames or the frames of any lower-priority process. This approach allows a high-priority process to increase its frame allocation at the expense of a low-priority process. Whereas with a local replacement strategy, the number of frames allocated to a process does not change, with global replacement, a process may happen to select only frames allocated to other processes, thus increasing the number of frames allocated to it (assuming that other processes do not choose its frames for replacement).

One problem with a global replacement algorithm is that the set of pages in memory for a process depends not only on the paging behavior of that pro- cess, but also on the paging behavior of other processes. Therefore, the same process may perform quite differently (for example, taking 0.5 seconds for one execution and 4.3 seconds for the next execution) because of totally external circumstances. Such is not the case with a local replacement algorithm. Under local replacement, the set of pages in memory for a process is affected by the paging behavior of only that process. Local replacement might hinder a pro- cess, however, by not making available to it other, less used pages of memory. Thus, global replacement generally results in greater system throughput. It is therefore the more commonly used method.

MAJOR ANDMINOR PAGE FAULTS

As described in Section 10.2.1, a page fault occurs when a page does not have a valid mapping in the address space of a process. Operating systems generally distinguish between two types of page faults: major and minor faults. (Windows refers to major and minor faults as hard and soft faults, respectively.) A major page fault occurs when a page is referenced and the page is not in memory. Servicing a major page fault requires reading the desired page from the backing store into a free frame and updating the page table. Demand paging typically generates an initially high rate of major page faults.

Minor page faults occur when a process does not have a logical mapping to a page, yet that page is in memory. Minor faults can occur for one of two reasons. First, a process may reference a shared library that is in memory, but the process does not have a mapping to it in its page table. In this instance, it is only necessary to update the page table to refer to the existing page in memory. A second cause of minor faults occurs when a page is reclaimed from a process and placed on the free-frame list, but the page has not yet been zeroed out and allocated to another process. When this kind of fault occurs, the frame is removed from the free-frame list and reassigned to the process. Asmight be expected, resolving aminor page fault is typically much less time consuming than resolving a major page fault.

You can observe the number of major and minor page faults in a Linux system using the command ps -eo min flt,maj flt,cmd, which outputs the number of minor and major page faults, as well as the command that launched the process.An example output of this ps commandappears below:

MINFL MAJFL CMD

186509 32 /usr/lib/systemd/systemd-logind

76822 9 /usr/sbin/sshd -D

1937 0 vim 10.tex

699 14 /sbin/auditd -n

Here, it is interesting to note that, for most commands, the number of major page faults is generally quite low,whereas the number ofminor faults ismuch higher. This indicates that Linux processes likely take significant advantage of shared libraries as, once a library is loaded in memory, subsequent page faults are only minor faults.

Next, we focus on one possible strategy that we can use to implement a global page-replacement policy. With this approach, we satisfy all memory requests from the free-frame list, but rather than waiting for the list to drop to zero before we begin selecting pages for replacement, we trigger page replace- ment when the list falls below a certain threshold. This strategy attempts to ensure there is always sufficient free memory to satisfy new requests.

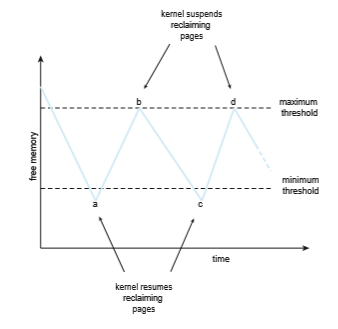

Such a strategy is depicted in Figure 10.18. The strategy’s purpose is to keep the amount of free memory above a minimum threshold. When it drops

below this threshold, a kernel routine is triggered that begins reclaiming pages from all processes in the system (typically excluding the kernel). Such kernel routines are often known as reapers, and they may apply any of the page- replacement algorithms covered in Section 10.4. When the amount of free memory reaches themaximum threshold, the reaper routine is suspended, only to resume once free memory again falls below the minimum threshold.

In Figure 10.18, we see that at point a the amount of free memory drops below the minimum threshold, and the kernel begins reclaiming pages and adding them to the free-frame list. It continues until the maximum threshold is reached (point b). Over time, there are additional requests for memory, and at point c the amount of free memory again falls below the minimum threshold. Page reclamation resumes, only to be suspended when the amount of free memory reaches the maximum threshold (point d). This process continues as long as the system is running.

As mentioned above, the kernel reaper routine may adopt any page- replacement algorithm, but typically it uses some form of LRU approximation. Consider what may happen, though, if the reaper routine is unable to maintain the list of free frames below the minimum threshold. Under these circum-

stances, the reaper routine may begin to reclaim pages more aggressively. For example, perhaps it will suspend the second-chance algorithm and use pure FIFO. Another, more extreme, example occurs in Linux; when the amount of free memory falls to very low levels, a routine known as the out-of-memory (OOM) killer selects a process to terminate, thereby freeing its memory. How does Linux determine which process to terminate? Each process has what is known as an OOM score, with a higher score increasing the likelihood that the process could be terminated by the OOM killer routine. OOM scores are calcu- lated according to the percentage of memory a process is using—the higher the percentage, the higher the OOM score. (OOM scores can be viewed in the /proc file system, where the score for a process with pid 2500 can be viewed as /proc/2500/oom score.)

In general, not only can reaper routines vary how aggressively they reclaim memory, but the values of the minimum and maximum thresholds can be varied as well. These values can be set to default values, but some systems may allow a system administrator to configure them based on the amount of physical memory in the system.

Non-Uniform Memory Access

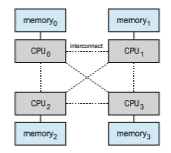

Thus far in our coverage of virtual memory, we have assumed that all main memory is created equal—or at least that it is accessed equally. On non- uniform memory access (NUMA) systems with multiple CPUs (Section 1.3.2), that is not the case. On these systems, a given CPU can access some sections of main memory faster than it can access others. These performance differences are caused by how CPUs and memory are interconnected in the system. Such a system is made up of multiple CPUs, each with its own local memory (Figure 10.19). The CPUs are organized using a shared system interconnect, and as you might expect, a CPU can access its local memory faster than memory local to another CPU. NUMA systems are without exception slower than systems in which all accesses to main memory are treated equally. However, as described in Section 1.3.2, NUMA systems can accommodate more CPUs and therefore achieve greater levels of throughput and parallelism.

Managing which page frames are stored at which locations can signifi- cantly affect performance in NUMA systems. If we treat memory as uniform in such a system, CPUs may wait significantly longer for memory access than if we modify memory allocation algorithms to take NUMA into account. We described some of these modifications in Section 5.5.4. Their goal is to have memory frames allocated “as close as possible” to the CPU onwhich the process is running. (The definition of close is “with minimum latency,” which typically means on the same system board as the CPU). Thus, when a process incurs a page fault, a NUMA-aware virtual memory system will allocate that process a frame as close as possible to the CPU on which the process is running.

To take NUMA into account, the scheduler must track the last CPU on which each process ran. If the scheduler tries to schedule each process onto its previous CPU, and the virtual memory system tries to allocate frames for the process close to the CPU on which it is being scheduled, then improved cache hits and decreased memory access times will result.

The picture is more complicated once threads are added. For example, a process with many running threads may end up with those threads scheduled onmany different system boards. How should the memory be allocated in this case?

As we discussed in Section 5.7.1, Linux manages this situation by having the kernel identify a hierarchy of scheduling domains. The Linux CFS scheduler does not allow threads to migrate across different domains and thus incur memory access penalties. Linux also has a separate free-frame list for each NUMAnode, thereby ensuring that a thread will be allocated memory from the node on which it is running. Solaris solves the problem similarly by creating lgroups (for “locality groups”) in the kernel. Each lgroup gathers together CPUs and memory, and each CPU in that group can access any memory in the group within a defined latency interval. In addition, there is a hierarchy of lgroups based on the amount of latency between the groups, similar to the hierarchy of scheduling domains in Linux. Solaris tries to schedule all threads of a process and allocate all memory of a process within an lgroup. If that is not possible, it picks nearby lgroups for the rest of the resources needed. This practiceminimizes overall memory latency andmaximizes CPU cache hit rates.