Contiguous Memory Allocation

The main memory must accommodate both the operating system and the various user processes. We therefore need to allocate main memory in the most efficientway possible. This section explains one earlymethod, contiguous memory allocation.

The memory is usually divided into two partitions: one for the operating system and one for the user processes. We can place the operating system in either low memory addresses or high memory addresses. This decision depends onmany factors, such as the location of the interrupt vector. However, many operating systems (including Linux and Windows) place the operating system in high memory, and therefore we discuss only that situation.

We usually want several user processes to reside in memory at the same time. We therefore need to consider how to allocate available memory to the processes that are waiting to be brought into memory. In contiguous mem- ory allocation, each process is contained in a single section of memory that is contiguous to the section containing the next process. Before discussing this memory allocation scheme further, though, we must address the issue of memory protection.

Memory Protection

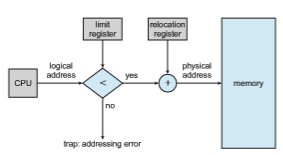

We can prevent a process from accessing memory that it does not own by combining two ideas previously discussed. If we have a system with a relo- cation register (Section 9.1.3), together with a limit register (Section 9.1.1), we accomplish our goal. The relocation register contains the value of the smallest physical address; the limit register contains the range of logical addresses (for example, relocation = 100040 and limit = 74600). Each logical address must fall within the range specified by the limit register. The MMU maps the log- ical address dynamically by adding the value in the relocation register. This mapped address is sent to memory (Figure 9.6).

When the CPU scheduler selects a process for execution, the dispatcher loads the relocation and limit registers with the correct values as part of the context switch. Because every address generated by a CPU is checked against these registers, we can protect both the operating system and the other users’ programs and data from being modified by this running process.

The relocation-register scheme provides an effectiveway to allow the oper- ating system’s size to change dynamically. This flexibility is desirable in many situations. For example, the operating system contains code and buffer space for device drivers. If a device driver is not currently in use, it makes little sense to keep it in memory; instead, it can be loaded into memory only when it is needed. Likewise, when the device driver is no longer needed, it can be removed and its memory allocated for other needs.

Figure 9.6 Hardware support for relocation and limit registers.

Memory Allocation

Nowweare ready to turn tomemory allocation.One of the simplestmethods of allocating memory is to assign processes to variably sized partitions in mem- ory, where each partition may contain exactly one process. In this variable- partition scheme, the operating system keeps a table indicating which parts of memory are available andwhich are occupied. Initially, all memory is available for user processes and is considered one large block of available memory, a hole. Eventually, as you will see, memory contains a set of holes of various sizes.

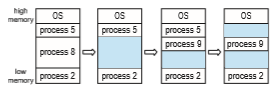

Figure 9.7 depicts this scheme. Initially, the memory is fully utilized, con- taining processes 5, 8, and 2. After process 8 leaves, there is one contiguous hole. Later on, process 9 arrives and is allocated memory. Then process 5 departs, resulting in two noncontiguous holes.

As processes enter the system, the operating system takes into account the memory requirements of each process and the amount of available memory space in determining which processes are allocated memory. When a process is allocated space, it is loaded into memory, where it can then compete for CPU time. When a process terminates, it releases its memory, which the operating system may then provide to another process.

What happens when there isn’t sufficient memory to satisfy the demands of an arriving process? One option is to simply reject the process and provide an appropriate error message. Alternatively, we can place such processes into a wait queue. When memory is later released, the operating system checks the wait queue to determine if it will satisfy the memory demands of a waiting process.

In general, as mentioned, the memory blocks available comprise a set of holes of various sizes scattered throughout memory. When a process arrives and needs memory, the system searches the set for a hole that is large enough for this process. If the hole is too large, it is split into two parts. One part is allocated to the arriving process; the other is returned to the set of holes. When a process terminates, it releases its block of memory, which is then placed back in the set of holes. If the newhole is adjacent to other holes, these adjacent holes are merged to form one larger hole.

This procedure is a particular instance of the general dynamic storage- allocation problem, which concerns how to satisfy a request of size n from a list of free holes. There aremany solutions to this problem. The first-fit, best-fi , and worst-fi strategies are the ones most commonly used to select a free hole from the set of available holes.

• First fit. Allocate the first hole that is big enough. Searching can start either at the beginning of the set of holes or at the location where the previous first-fit search ended. We can stop searching as soon as we find a free hole that is large enough.

• Best fi . Allocate the smallest hole that is big enough. We must search the entire list, unless the list is ordered by size. This strategy produces the smallest leftover hole.

• Worst fit. Allocate the largest hole. Again, we must search the entire list, unless it is sorted by size. This strategy produces the largest leftover hole, which may be more useful than the smaller leftover hole from a best-fit approach.

Simulations have shown that both first fit and best fit are better than worst fit in terms of decreasing time and storage utilization. Neither first fit nor best fit is clearly better than the other in terms of storage utilization, but first fit is generally faster.

Fragmentation

Both the first-fit and best-fit strategies for memory allocation suffer from exter- nal fragmentation. As processes are loaded and removed from memory, the free memory space is broken into little pieces. External fragmentation exists when there is enough total memory space to satisfy a request but the available spaces are not contiguous: storage is fragmented into a large number of small holes. This fragmentation problem can be severe. In the worst case, we could have a block of free (or wasted) memory between every two processes. If all these small pieces of memory were in one big free block instead, we might be able to run several more processes.

Whether we are using the first-fit or best-fit strategy can affect the amount of fragmentation. (First fit is better for some systems, whereas best fit is better for others.) Another factor is which end of a free block is allocated. (Which is the leftover piece—the one on the top or the one on the bottom?) No matter which algorithm is used, however, external fragmentation will be a problem.

Depending on the total amount ofmemory storage and the average process size, external fragmentation may be a minor or a major problem. Statistical analysis of first fit, for instance, reveals that, even with some optimization, given N allocated blocks, another 0.5 N blocks will be lost to fragmentation. That is, one-third of memory may be unusable! This property is known as the 50-percent rule.

Memory fragmentation can be internal as well as external. Consider a multiple-partition allocation scheme with a hole of 18,464 bytes. Suppose that the next process requests 18,462 bytes. If we allocate exactly the requested block, we are left with a hole of 2 bytes. The overhead to keep track of this hole will be substantially larger than the hole itself. The general approach to avoiding this problem is to break the physical memory into fixed-sized blocks and allocate memory in units based on block size. With this approach, the memory allocated to a process may be slightly larger than the requested memory. The difference between these two numbers is internal fragmentation —unused memory that is internal to a partition.

One solution to the problem of external fragmentation is compaction. The goal is to shuffle the memory contents so as to place all free memory together in one large block. Compaction is not always possible, however. If relocation is static and is done at assembly or load time, compaction cannot be done. It is possible only if relocation is dynamic and is done at execution time. If addresses are relocated dynamically, relocation requires only moving the program and data and then changing the base register to reflect the new base address. When compaction is possible, we must determine its cost. The simplest compaction algorithm is tomove all processes toward one end ofmemory; all holesmove in the other direction, producing one large hole of availablememory. This scheme can be expensive.

Another possible solution to the external-fragmentation problem is to per- mit the logical address space of processes to be noncontiguous, thus allowing a process to be allocated physical memory wherever such memory is available. This is the strategy used in paging, the most common memory-management technique for computer systems. We describe paging in the following section.

Fragmentation is a general problem in computing that can occur wherever we must manage blocks of data. We discuss the topic further in the storage management chapters (Chapter 11 through Chapter 15).