NFS

Network file systems are commonplace. They are typically integrated with the overall directory structure and interface of the client system. NFS is a good example of a widely used, well implemented client–server network file system. Here, we use it as an example to explore the implementation details of network file systems.

NFS is both an implementation and a specification of a software system for accessing remote files across LANs (or even WANs). NFS is part of ONC+, which most UNIX vendors and some PC operating systems support. The implementa- tion described here is part of the Solaris operating system, which is a modified version of UNIX SVR4. It uses either the TCP or UDP/IP protocol (depending on the interconnecting network). The specification and the implementation are intertwined in our description of NFS. Whenever detail is needed, we refer to the Solaris implementation; whenever the description is general, it applies to the specification also.

There are multiple versions of NFS, with the latest being Version 4. Here, we describe Version 3, which is the version most commonly deployed.

Overview

NFS views a set of interconnected workstations as a set of independent machines with independent file systems. The goal is to allow some degree of sharing among these file systems (on explicit request) in a transparent manner. Sharing is based on a client–server relationship. Amachine may be, and often is, both a client and a server. Sharing is allowed between any pair of machines. To ensure machine independence, sharing of a remote file system affects only the client machine and no other machine.

So that a remote directory will be accessible in a transparent manner from a particular machine—say, from**M1**—a client of that machine must first carry out a mount operation. The semantics of the operation involve mounting a remote directory over a directory of a local file system. Once the mount oper- ation is completed, the mounted directory looks like an integral subtree of the local file system, replacing the subtree descending from the local directory. The local directory becomes the name of the root of the newly mounted directory. Specification of the remote directory as an argument for the mount operation is not done transparently; the location (or host name) of the remote directory has to be provided. However, from then on, users on machine M1 can access files in the remote directory in a totally transparent manner.

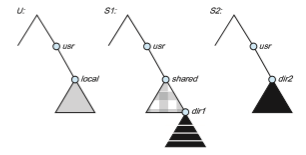

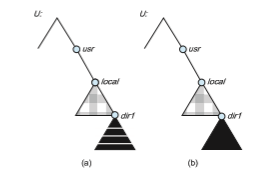

To illustrate file mounting, consider the file system depicted in Figure 15.6, where the triangles represent subtrees of directories that are of interest. The figure shows three independent file systems of machines named U, S1, and S2. At this point, on each machine, only the local files can be accessed. Figure 15.7(a) shows the effects of mounting S1:/usr/shared over U:/usr/local. This figure depicts the view users on U have of their file system. After the mount is complete, they can access any file within the dir1 directory using the prefix /usr/local/dir1. The original directory /usr/local on that machine is no longer visible.

Subject to access-rights accreditation, any file system, or any directory within a file system, can be mounted remotely on top of any local directory.

Disklessworkstations can evenmount their own roots from servers. Cascading mounts are also permitted in some NFS implementations. That is, a file system can bemounted over another file system that is remotelymounted, not local. A machine is affected by only those mounts that it has itself invoked. Mounting a remote file systemdoes not give the client access to other file systems thatwere, by chance, mounted over the former file system. Thus, the mount mechanism does not exhibit a transitivity property.

In Figure 15.7(b), we illustrate cascading mounts. The figure shows the result of mounting S2:/usr/dir2 over U:/usr/local/dir1, which is already remotely mounted from S1. Users can access files within dir2 on U using the prefix /usr/local/dir1. If a shared file system ismounted over a user’s home directories on all machines in a network, the user can log into any workstation and get his or her home environment. This property permits user mobility.

One of the design goals of NFS was to operate in a heterogeneous environ- ment of different machines, operating systems, and network architectures. The

NFS specification is independent of thesemedia. This independence is achieved through the use of RPC primitives built on top of an external data representa- tion (XDR) protocol used between two implementation-independent interfaces. Hence, if the system’s heterogeneous machines and file systems are properly interfaced to NFS, file systems of different types can be mounted both locally and remotely.

The NFS specification distinguishes between the services provided by a mount mechanism and the actual remote-file-access services. Accordingly, two separate protocols are specified for these services: a mount protocol and a pro- tocol for remote file accesses, the NFS protocol. The protocols are specified as sets of RPCs. These RPCs are the building blocks used to implement transparent remote file access.

The Mount Protocol

The mount protocol establishes the initial logical connection between a server and a client. In Solaris, each machine has a server process, outside the kernel, performing the protocol functions.

A mount operation includes the name of the remote directory to be mounted and the name of the server machine storing it. The mount request is mapped to the corresponding RPC and is forwarded to the mount server running on the specific server machine. The server maintains an export list that specifies local file systems that it exports for mounting, along with names of machines that are permitted to mount them. (In Solaris, this list is the /etc/dfs/dfstab, which can be edited only by a superuser.) The specification can also include access rights, such as read only. To simplify the maintenance of export lists and mount tables, a distributed naming scheme can be used to hold this information and make it available to appropriate clients.

Recall that any directory within an exported file system can be mounted remotely by an accredited machine. A component unit is such a directory. When the server receives a mount request that conforms to its export list, it returns to the client a file handle that serves as the key for further accesses to files within the mounted file system. The file handle contains all the informa- tion that the server needs to distinguish an individual file it stores. In UNIX terms, the file handle consists of a file-system identifier and an inode number to identify the exact mounted directory within the exported file system.

The server also maintains a list of the client machines and the correspond- ing currently mounted directories. This list is used mainly for administrative purposes—for instance, for notifying all clients that the server is going down. Only through addition and deletion of entries in this list can the server state be affected by the mount protocol.

Usually, a systemhas a staticmounting preconfiguration that is established at boot time (/etc/vfstab in Solaris); however, this layout can bemodified. In addition to the actual mount procedure, the mount protocol includes several other procedures, such as unmount and return export list.

The NFS Protocol

The NFS protocol provides a set of RPCs for remote file operations. The proce- dures support the following operations:

NFS 613**

• Searching for a file within a directory

• Reading a set of directory entries

• Manipulating links and directories

• Accessing file attributes

• Reading and writing files

These procedures can be invoked only after a file handle for the remotely mounted directory has been established.

The omission of open and close operations is intentional. A prominent feature of NFS servers is that they are stateless. Servers do not maintain infor- mation about their clients from one access to another. No parallels to UNIX’s open-files table or file structures exist on the server side. Consequently, each request has to provide a full set of arguments, including a unique file identifier and an absolute offset inside the file for the appropriate operations. The result- ing design is robust; no special measures need be taken to recover a server after a crash. File operations must be idempotent for this purpose—that is, the same operation performed multiple times must have the same effect as if it had only been performed once. To achieve idempotence, every NFS request has a sequence number, allowing the server to determine if a request has been duplicated or if any are missing.

Maintaining the list of clients that we mentioned seems to violate the statelessness of the server. However, this list is not essential for the correct operation of the client or the server, and hence it does not need to be restored after a server crash. Consequently, it may include inconsistent data and is treated as only a hint.

A further implication of the stateless-server philosophy and a result of the synchrony of an RPC is that modified data (including indirection and status blocks) must be committed to the server’s disk before results are returned to the client. That is, a client can cache write blocks, but when it flushes them to the server, it assumes that they have reached the server’s disks. The server must write all NFS data synchronously. Thus, a server crash and recovery will be invisible to a client; all blocks that the server ismanaging for the clientwill be intact. The resulting performance penalty can be large, because the advantages of caching are lost. Performance can be increased by using storagewith its own nonvolatile cache (usually battery-backed-up memory). The disk controller acknowledges the disk write when the write is stored in the nonvolatile cache. In essence, the host sees a very fast synchronous write. These blocks remain intact even after a system crash and are written from this stable storage to disk periodically.

A single NFS write procedure call is guaranteed to be atomic and is not intermixed with other write calls to the same file. The NFS protocol, however, does not provide concurrency-controlmechanisms.Awrite() systemcallmay be broken down into several RPC writes, because each NFS write or read call can contain up to 8 KB of data and UDP packets are limited to 1,500 bytes. As a result, two users writing to the same remote file may get their data intermixed. The claim is that, because lock management is inherently stateful, a service outside the NFS should provide locking (and Solaris does). Users are advised to coordinate access to shared files usingmechanisms outside the scope of NFS.

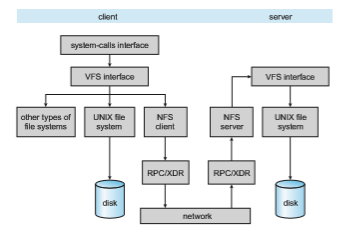

NFS is integrated into the operating system via a VFS. As an illustration of the architecture, let’s trace how an operation on an already-open remote file is handled (follow the example in Figure 15.8). The client initiates the operation with a regular system call. The operating-system layer maps this call to a VFS operation on the appropriate vnode. The VFS layer identifies the file as a remote one and invokes the appropriate NFS procedure. An RPC call is made to the NFS service layer at the remote server. This call is reinjected to the VFS layer on the remote system, which finds that it is local and invokes the appropriate file- systemoperation. This path is retraced to return the result.An advantage of this architecture is that the client and the server are identical; thus, a machine may be a client, or a server, or both. The actual service on each server is performed by kernel threads.

Path-Name Translation

Path-name translation in NFS involves the parsing of a path name such as /usr/local/dir1/file.txt into separate directory entries, or components: (1) usr, (2) local, and (3) dir1. Path-name translation is done by breaking the path into component names and performing a separate NFS lookup call for every pair of component name and directory vnode. Once a mount point is crossed, every component lookup causes a separate RPC to the server. This expensive path-name-traversal scheme is needed, since the layout of each client’s logical name space is unique, dictated by the mounts the client has performed. It would be much more efficient to hand a server a path name and receive a target vnode once a mount point is encountered. At any point, however, there might be another mount point for the particular client of which the stateless server is unaware.

So that lookup is fast, a directory-name-lookup cache on the client side holds the vnodes for remote directory names. This cache speeds up references to files with the same initial path name. The directory cache is discarded when attributes returned from the server do not match the attributes of the cached vnode.

Recall that some implementations of NFS allow mounting a remote file system on top of another already-mounted remote file system (a cascading mount). When a client has a cascading mount, more than one server can be involved in a path-name traversal. However, when a client does a lookup on a directory on which the server has mounted a file system, the client sees the underlying directory instead of the mounted directory.

Remote Operations

With the exception of opening and closing files, there is an almost one-to-one correspondence between the regular UNIX system calls for file operations and the NFS protocol RPCs. Thus, a remote file operation can be translated directly to the corresponding RPC. Conceptually, NFS adheres to the remote-service paradigm; but in practice, buffering and caching techniques are employed for the sake of performance. No direct correspondence exists between a remote operation and an RPC. Instead, file blocks and file attributes are fetched by the RPCs and are cached locally. Future remote operations use the cached data, subject to consistency constraints.

There are two caches: the file-attribute (inode-information) cache and the file-blocks cache. When a file is opened, the kernel checks with the remote server to determine whether to fetch or revalidate the cached attributes. The cached file blocks are used only if the corresponding cached attributes are up to date. The attribute cache is updated whenever new attributes arrive from the server. Cached attributes are, by default, discarded after 60 seconds. Both read-ahead and delayed-write techniques are used between the server and the client. Clients do not free delayed-write blocks until the server confirms that the data have been written to disk. Delayed-write is retained even when a file is opened concurrently, in conflicting modes. Hence, UNIX semantics (Section 15.7.1) are not preserved.

Tuning the system for performance makes it difficult to characterize the consistency semantics of NFS. New files created on a machine may not be visible elsewhere for 30 seconds. Furthermore, writes to a file at one site may or may not be visible at other sites that have this file open for reading. New opens of a file observe only the changes that have already been flushed to the server. Thus, NFS provides neither strict emulation of UNIX semantics nor the session semantics of Andrew (Section 15.7.2). In spite of these drawbacks, the utility and good performance of the mechanism make it the most widely used multi-vendor-distributed system in operation.

Summary

• General-purpose operating systems provide many file-system types, from special-purpose through general.

• Volumes containing file systems can be mounted into the computer’s file- system space.

• Depending on the operating system, the file-system space is seamless (mounted file systems integrated into the directory structure) or distinct (each mounted file system having its own designation).

• At least one file system must be bootable for the system to be able to start —that is, it must contain an operating system. The boot loader is run first; it is a simple program that is able to find the kernel in the file system, load it, and start its execution. Systems can containmultiple bootable partitions, letting the administrator choose which to run at boot time.

• Most systems are multi-user and thus must provide a method for file shar- ing and file protection. Frequently, files and directories include metadata, such as owner, user, and group access permissions.

• Mass storage partitions are used either for raw block I/O or for file systems. Each file system resides in a volume, which can be composed of one partition or multiple partitions working together via a volume manager.

• To simplify implementation of multiple file systems, an operating system can use a layered approach, with a virtual file-system interface making access to possibly dissimilar file systems seamless.

• Remote file systems can be implemented simply by using a program such as ftp or the web servers and clients in theWorldWideWeb, or with more functionality via a client–server model. Mount requests and user IDs must be authenticated to prevent unapproved access.

• Client–server facilities do not natively share information, but a distributed information system such as DNS can be used to allow such sharing, pro- viding a unified user name space, password management, and system identification. For example, Microsoft CIFS uses active directory, which employs a version of the Kerberos network authentication protocol to pro- vide a full set of naming and authentication services among the computers in a network.

• Once file sharing is possible, a consistency semantics model must be cho- sen and implemented to moderate multiple concurrent access to the same file. Semantics models include UNIX, session, and immutable-shared-files semantics.

• NFS is an example of a remote file system, providing clients with seam- less access to directories, files, and even entire file systems. A full-featured remote file system includes a communication protocol with remote opera- tions and path-name translation.

Practice Exercises

15.1 Explain how the VFS layer allows an operating system to support mul- tiple types of file systems easily.

15.2 Why have more than one file system type on a given system?

15.3 On a Unix or Linux system that implements the procfs file system, determine how to use the procfs interface to explore the process name space. What aspects of processes can be viewed via this interface? How would the same information be gathered on a system lacking the procfs file system?

15.4 Why do some systems integrate mounted file systems into the root file system naming structure, while others use a separate naming method for mounted file systems?

15.5 Given a remote file access facility such as ftp, why were remote file systems like NFS created?

Further Reading

The internals of the BSD UNIX system are covered in full in [McKusick et al. (2015)]. Details concerning file systems for Linux can be found in [Love (2010)].

The network file system (NFS) is discussed in [Callaghan (2000)]. NFS Ver- sion 4 is a standard described at http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc3530.txt. [Ouster- hout (1991)] discusses the role of distributed state in networked file systems. NFS and the UNIX file system (UFS) are described in [Mauro and McDougall (2007)].

The Kerberos network authentication protocol is explored in https://web.mit.edu/kerberos/.

Bibliography

[Callaghan (2000)] B. Callaghan, NFS Illustrated, Addison-Wesley (2000).

[Love (2010)] R. Love, Linux Kernel Development, Third Edition, Developer’s Library (2010).

[Mauro and McDougall (2007)] J. Mauro and R. McDougall, Solaris Internals: Core Kernel Architecture, Prentice Hall (2007).

[McKusick et al. (2015)] M. K. McKusick, G. V. Neville-Neil, and R. N. M. Wat- son,The Design and Implementation of the FreeBSDUNIXOperating System–Second Edition, Pearson (2015).

[Ousterhout (1991)] J. Ousterhout. “The Role of Distributed State”. In CMU Computer Science: a 25th Anniversary Commemorative, R. F. Rashid, Ed., Addison- Wesley (1991).

15.6 Assume that in a particular augmentation of a remote-file-access pro- tocol, each client maintains a name cache that caches translations from file names to corresponding file handles. What issues should we take into account in implementing the name cache?

15.7 Given a mounted file system with write operations underway, and a system crash or power loss, what must be done before the file system is remounted if: (a) The file system is not log-structured? (b) The file system is log-structured?

15.8 Why do operating systems mount the root file system automatically at boot time?

15.9 Why do operating systems require file systems other than root to be mounted?

EX-51