File-System Operations

As was described in Section 13.1.2, operating systems implement open() and close() systems calls for processes to request access to file contents. In this section, we delve into the structures and operations used to implement file- system operations.

Overview

Several on-storage and in-memory structures are used to implement a file system. These structures vary depending on the operating system and the file system, but some general principles apply.

On storage, the file system may contain information about how to boot an operating system stored there, the total number of blocks, the number and location of free blocks, the directory structure, and individual files. Many of these structures are detailed throughout the remainder of this chapter. Here, we describe them briefly:

• A boot control block (per volume) can contain information needed by the system to boot an operating system from that volume. If the disk does not contain an operating system, this block can be empty. It is typically the first block of a volume. In UFS, it is called the boot block. In NTFS, it is the partition boot sector.

• A volume control block (per volume) contains volume details, such as the number of blocks in the volume, the size of the blocks, a free-block count and free-block pointers, and a free-FCB count and FCB pointers. In UFS, this is called a superblock. In NTFS, it is stored in the master fil table.

• A directory structure (per file system) is used to organize the files. In UFS, this includes file names and associated inode numbers. In NTFS, it is stored in the master file table.

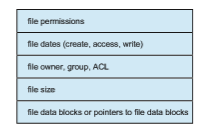

• A per-file FCB containsmany details about the file. It has a unique identifier number to allow association with a directory entry. In NTFS, this informa- tion is actually stored within the master file table, which uses a relational database structure, with a row per file.

The in-memory information is used for both file-system management and performance improvement via caching. The data are loaded at mount time, updated during file-system operations, and discarded at dismount. Several types of structures may be included.

• An in-memory mount table contains information about each mounted volume.

• An in-memory directory-structure cache holds the directory information of recently accessed directories. (For directories at which volumes are mounted, it can contain a pointer to the volume table.)

• The system-wide open-fil table contains a copy of the FCB of each open file, as well as other information.

• The per-process open-fil table contains pointers to the appropriate entries in the system-wide open-file table, as well as other information, for all files the process has open.

• Buffers hold file-system blocks when they are being read from or written to a file system.

To create a new file, a process calls the logical file system. The logical file system knows the format of the directory structures. To create a new file, it allocates a new FCB. (Alternatively, if the file-system implementation creates all FCBs at file-system creation time, an FCB is allocated from the set of free FCBs.) The system then reads the appropriate directory into memory, updates it with the newfile name and FCB, andwrites it back to the file system.Atypical FCB is shown in Figure 14.2.

Some operating systems, including UNIX, treat a directory exactly the same as a file—one with a “type” field indicating that it is a directory. Other oper-

ating systems, including Windows, implement separate system calls for files and directories and treat directories as entities separate from files. Whatever the larger structural issues, the logical file system can call the file-organization module to map the directory I/O into storage block locations, which are passed on to the basic file system and I/O control system.

Usage

Now that a file has been created, it can be used for I/O. First, though, it must be opened. The open() call passes a file name to the logical file system. The open() systemcall first searches the system-wide open-file table to see if the file is already in use by another process. If it is, a per-process open-file table entry is created pointing to the existing system-wide open-file table. This algorithm can save substantial overhead. If the file is not already open, the directory structure is searched for the given file name. Parts of the directory structure are usually cached in memory to speed directory operations. Once the file is found, the FCB is copied into a system-wide open-file table in memory. This table not only stores the FCB but also tracks the number of processes that have the file open.

Next, an entry is made in the per-process open-file table, with a pointer to the entry in the system-wide open-file table and some other fields. These other fieldsmay include a pointer to the current location in the file (for the next read() or write() operation) and the access mode in which the file is open. The open() call returns a pointer to the appropriate entry in the per-process file-system table. All file operations are then performed via this pointer. The file name may not be part of the open-file table, as the system has no use for it once the appropriate FCB is located on disk. It could be cached, though, to save time on subsequent opens of the same file. The name given to the entry varies. UNIX systems refer to it as a fil descriptor; Windows refers to it as a fil handle.

When a process closes the file, the per-process table entry is removed, and the system-wide entry’s open count is decremented. When all users that have opened the file close it, any updatedmetadata are copied back to the disk-based directory structure, and the system-wide open-file table entry is removed.

The caching aspects of file-system structures should not be overlooked. Most systems keep all information about an open file, except for its actual data blocks, inmemory. The BSD UNIX system is typical in its use of caches wherever disk I/O can be saved. Its average cache hit rate of 85 percent shows that these techniques are well worth implementing. The BSD UNIX system is described fully in Appendix C.

The operating structures of a file-system implementation are summarized in Figure 14.3.