Example: The WAFL File System

Because secondary-storage I/O has such a huge impact on systemperformance, file-system design and implementation command quite a lot of attention from system designers. Some file systems are general purpose, in that they can provide reasonable performance and functionality for a wide variety of file sizes, file types, and I/O loads. Others are optimized for specific tasks in an attempt to provide better performance in those areas than general-purpose

file systems. The write-anywhere file layout (WAFL) from NetApp, Inc. is an example of this sort of optimization. WAFL is a powerful, elegant file system optimized for random writes.

WAFL is used exclusively on network file servers produced by NetApp and is meant for use as a distributed file system. It can provide files to clients via the NFS, CIFS, iSCSI, ftp, and http protocols, although it was designed just for NFS and CIFS. When many clients use these protocols to talk to a file server, the server may see a very large demand for random reads and an even larger demand for random writes. The NFS and CIFS protocols cache data from read operations, so writes are of the greatest concern to file-server creators.

WAFL is used on file servers that include an NVRAM cache for writes. The WAFL designers took advantage of running on a specific architecture to optimize the file system for random I/O, with a stable-storage cache in front. Ease of use is one of the guiding principles of WAFL. Its creators also designed it to include a new snapshot functionality that creates multiple read-only copies of the file system at different points in time, as we shall see.

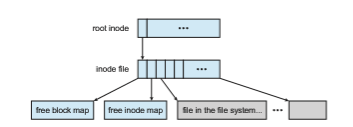

The file system is similar to the Berkeley Fast File System, with many modifications. It is block-based and uses inodes to describe files. Each inode contains 16 pointers to blocks (or indirect blocks) belonging to the file described by the inode. Each file system has a root inode. All of themetadata lives in files. All inodes are in one file, the free-block map in another, and the free-inode map in a third, as shown in Figure 14.12. Because these are standard files, the data blocks are not limited in location and can be placed anywhere. If a file system is expanded by addition of disks, the lengths of the metadata files are automatically expanded by the file system.

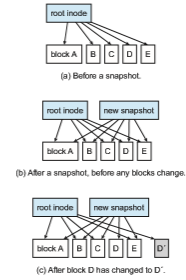

Thus, a WAFL file system is a tree of blocks with the root inode as its base. To take a snapshot, WAFL creates a copy of the root inode. Any file or metadata updates after that go to new blocks rather than overwriting their existing blocks. The new root inode points to metadata and data changed as a result of these writes. Meanwhile, the snapshot (the old root inode) still points to the old blocks, which have not been updated. It therefore provides access to the file system just as it was at the instant the snapshot was made—and takes very little storage space to do so. In essence, the extra space occupied by a snapshot consists of just the blocks that have been modified since the snapshot was taken.

An important change frommore standard file systems is that the free-block map has more than one bit per block. It is a bitmap with a bit set for each snapshot that is using the block. When all snapshots that have been using the block are deleted, the bitmap for that block is all zeros, and the block is free to be reused. Used blocks are never overwritten, so writes are very fast, because a write can occur at the free block nearest the current head location. There are many other performance optimizations in WAFL as well.

Many snapshots can exist simultaneously, so one can be taken each hour of the day and each day of the month, for example. A user with access to these snapshots can access files as they were at any of the times the snapshots were taken. The snapshot facility is also useful for backups, testing, versioning, and so on. WAFL’s snapshot facility is very efficient in that it does not even require that copy-on-write copies of each data block be taken before the block is modified. Other file systems provide snapshots, but frequently with less efficiency. WAFL snapshots are depicted in Figure 14.13.

Newer versions of WAFL actually allow read–write snapshots, known as clones. Clones are also efficient, using the same techniques as shapshots. In this case, a read-only snapshot captures the state of the file system, and a clone refers back to that read-only snapshot. Any writes to the clone are stored in new blocks, and the clone’s pointers are updated to refer to the new blocks. The original snapshot is unmodified, still giving a view into the file system as

THE APPLE FILE SYSTEM

In 2017, Apple, Inc., released a new file system to replace its 30-year-old HFS+ file system. HFS+ had been stretched to add many new features, but as usual, this process added complexity, along with lines of code, and made adding more features more difficult. Starting from scratch on a blank page allows a design to start with current technologies and methodologies and provide the exact set of features needed.

Apple File System (APFS) is a good example of such a design. Its goal is to run on all current Apple devices, from the Apple Watch through the iPhone to the Mac computers. Creating a file system that works in watchOS, I/Os, tvOS, andmacOS is certainly a challenge. APFS is feature-rich, including 64-bit pointers, clones for files and directories, snapshots, space sharing, fast directory sizing, atomic safe-save primitives, copy-on-write design, encryp- tion (single- and multi-key), and I/O coalescing. It understands NVM as well as HDD storage.

Most of these features we’ve discussed, but there are a few new concepts worth exploring. Space sharing is a ZFS-like feature in which storage is avail- able as one or more large free spaces (containers) from which file systems can draw allocations (allowing APFS-formatted volumes to grow and shrink). Fast directory sizing provides quick used-space calculation and updating. Atomic safe-save is a primitive (available via API, not via file-system com- mands) that performs renames of files, bundles of files, and directories as single atomic operations. I/O coalescing is an optimization for NVM devices in which several small writes are gathered together into a large write to optimize write performance.

Apple chose not to implement RAID as part of the new APFS, instead depending on the existingApple RAID volumemechanism for software RAID. APFS is also compatible with HFS+, allowing easy conversion for existing deployments.

it was before the clone was updated. Clones can also be promoted to replace the original file system; this involves throwing out all of the old pointers and any associated old blocks. Clones are useful for testing and upgrades, as the original version is left untouched and the clone deleted when the test is done or if the upgrade fails.

Another feature that naturally results from theWAFLfile system implemen- tation is replication, the duplication and synchronization of a set of data over a network to another system. First, a snapshot of aWAFLfile system is duplicated to another system. When another snapshot is taken on the source system, it is relatively easy to update the remote system just by sending over all blocks contained in the new snapshot. These blocks are the ones that have changed between the times the two snapshotswere taken. The remote systemadds these blocks to the file system and updates its pointers, and the new system then is a duplicate of the source system as of the time of the second snapshot. Repeating this processmaintains the remote systemas a nearly up-to-date copy of the first system. Such replication is used for disaster recovery. Should the first system be destroyed, most of its data are available for use on the remote system.

Finally, note that the ZFS file system supports similarly efficient snapshots, clones, and replication, and those features are becoming more common in various file systems as time goes by.

Summary

• Most file systems reside on secondary storage, which is designed to hold a large amount of data permanently. The most common secondary-storage medium is the disk, but the use of NVM devices is increasing.

• Storage devices are segmented into partitions to control media use and to allowmultiple, possibly varying, file systems on a single device. These file systems are mounted onto a logical file system architecture to make them available for use.

• File systems are often implemented in a layered or modular structure. The lower levels deal with the physical properties of storage devices and communicatingwith them.Upper levels dealwith symbolic file names and logical properties of files.

• The various files within a file system can be allocated space on the storage device in three ways: through contiguous, linked, or indexed allocation. Contiguous allocation can suffer from external fragmentation. Direct access is very inefficient with linked allocation. Indexed allocation may require substantial overhead for its index block. These algorithms can be optimized in many ways. Contiguous space can be enlarged through extents to increase flexibility and to decrease external fragmentation. Indexed allocation can be done in clusters of multiple blocks to increase throughput and to reduce the number of index entries needed. Indexing in large clusters is similar to contiguous allocation with extents.

• Free-space allocation methods also influence the efficiency of disk-space use, the performance of the file system, and the reliability of secondary storage. The methods used include bit vectors and linked lists. Optimiza- tions include grouping, counting, and the FAT, which places the linked list in one contiguous area.

• Directory-management routines must consider efficiency, performance, and reliability. A hash table is a commonly used method, as it is fast and efficient. Unfortunately, damage to the table or a system crash can result in inconsistency between the directory information and the disk’s contents.

• A consistency checker can be used to repair damaged file-system struc- tures. Operating-system backup tools allow data to be copied to magnetic tape or other storage devices, enabling the user to recover from data loss or even entire device loss due to hardware failure, operating system bug, or user error.

• Due to the fundamental role that file systems play in system operation, their performance and reliability are crucial. Techniques such as log struc- tures and caching help improve performance, while log structures and RAID improve reliability. The WAFL file system is an example of optimiza- tion of performance to match a specific I/O load.

Practice Exercises

14.1 Consider a file currently consisting of 100 blocks. Assume that the file-control block (and the index block, in the case of indexed alloca- tion) is already in memory. Calculate how many disk I/O operations are required for contiguous, linked, and indexed (single-level) alloca- tion strategies, if, for one block, the following conditions hold. In the contiguous-allocation case, assume that there is no room to grow at the beginning but there is room to grow at the end. Also assume that the block information to be added is stored in memory.

a. The block is added at the beginning.

b. The block is added in the middle.

c. The block is added at the end.

d. The block is removed from the beginning.

e. The block is removed from the middle.

f. The block is removed from the end.

14.2 Whymust the bit map for file allocation be kept onmass storage, rather than in main memory?

14.3 Consider a system that supports the strategies of contiguous, linked, and indexed allocation.What criteria should be used in decidingwhich strategy is best utilized for a particular file?

14.4 One problem with contiguous allocation is that the user must preallo- cate enough space for each file. If the file grows to be larger than the space allocated for it, special actions must be taken. One solution to this problem is to define a file structure consisting of an initial con- tiguous area of a specified size. If this area is filled, the operating sys- tem automatically defines an overflow area that is linked to the initial contiguous area. If the overflow area is filled, another overflow area is allocated. Compare this implementation of a file with the standard contiguous and linked implementations.

14.5 How do caches help improve performance? Why do systems not use more or larger caches if they are so useful?

14.6 Why is it advantageous to the user for an operating system to dynami- cally allocate its internal tables?What are the penalties to the operating system for doing so?

Further Reading

The internals of the BSD UNIX system are covered in full in [McKusick et al. (2015)]. Details concerning file systems for Linux can be found in [Love (2010)]. The Google file system is described in [Ghemawat et al. (2003)]. FUSE can be found at http://fuse.sourceforge.net.

Log-structured file organizations for enhancing both performance and con- sistency are discussed in [Rosenblum and Ousterhout (1991)], [Seltzer et al. (1993)], and [Seltzer et al. (1995)]. Log-structured designs for networked file systems are proposed in [Hartman andOusterhout (1995)] and [Thekkath et al. (1997)].

The ZFS source code for spacemaps can be found at http://src.opensolaris.o rg/source/xref/onnv/onnv-gate/usr/src/uts/common/ fs/zfs/space map.c.

ZFS documentation can be found at http://www.opensolaris.org/os/commu nity/ZFS/docs.

The NTFS file system is explained in [Solomon (1998)], the Ext3 file system used in Linux is described in [Mauerer (2008)], and the WAFL file system is covered in [Hitz et al. (1995)].

Bibliography

[Ghemawat et al. (2003)] S. Ghemawat, H. Gobioff, and S.-T. Leung, “The Google File System”, Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (2003).

[Hartman and Ousterhout (1995)] J. H. Hartman and J. K. Ousterhout, “The Zebra Striped Network File System”, ACM Transactions on Computer Systems, Volume 13, Number 3 (1995), pages 274–310.

[Hitz et al. (1995)] D. Hitz, J. Lau, and M. Malcolm, “File System Design for an NFS File Server Appliance”, Technical report, NetApp (1995).

[Love (2010)] R. Love, Linux Kernel Development, Third Edition, Developer’s Library (2010).

[Mauerer (2008)] W. Mauerer, Professional Linux Kernel Architecture, John Wiley and Sons (2008).

[McKusick et al. (2015)] M. K. McKusick, G. V. Neville-Neil, and R. N. M. Wat- son,The Design and Implementation of the FreeBSDUNIXOperating System–Second Edition, Pearson (2015).

[Rosenblum and Ousterhout (1991)] M. Rosenblum and J. K. Ousterhout, “The Design and Implementation of a Log-Structured File System”, Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (1991), pages 1–15.

[Seltzer et al. (1993)] M. I. Seltzer, K. Bostic, M. K. McKusick, and C. Staelin, “An Implementation of a Log-Structured File System forUNIX”,USENIXWinter (1993), pages 307–326.

[Seltzer et al. (1995)] M. I. Seltzer, K. A. Smith, H. Balakrishnan, J. Chang, S. McMains, and V. N. Padmanabhan, “File System Logging Versus Clustering: A Performance Comparison”, USENIX Winter (1995), pages 249–264.

[Solomon (1998)] D. A. Solomon, Inside Windows NT, Second Edition, Microsoft Press (1998).

[Thekkath et al. (1997)] C. A. Thekkath, T. Mann, and E. K. Lee, “Frangipani: A Scalable Distributed File System”, Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (1997), pages 224–237.

Chapter 14 Exercises

14.7 Consider a file system that uses a modified contiguous-allocation scheme with support for extents. A file is a collection of extents, with each extent corresponding to a contiguous set of blocks. A key issue in such systems is the degree of variability in the size of the extents. What are the advantages and disadvantages of the following schemes?

a. All extents are of the same size, and the size is predetermined.

b. Extents can be of any size and are allocated dynamically.

c. Extents can be of a few fixed sizes, and these sizes are predeter- mined.

14.8 Contrast the performance of the three techniques for allocating disk blocks (contiguous, linked, and indexed) for both sequential and ran- dom file access.

14.9 What are the advantages of the variant of linked allocation that uses a FAT to chain together the blocks of a file?

14.10 Consider a system where free space is kept in a free-space list.

a. Suppose that the pointer to the free-space list is lost. Can the system reconstruct the free-space list? Explain your answer.

b. Consider a file system similar to the one used by UNIX with indexed allocation. How many disk I/O operations might be required to read the contents of a small local file at /a/b/c? Assume that none of the disk blocks is currently being cached.

c. Suggest a scheme to ensure that the pointer is never lost as a result of memory failure.

14.11 Some file systems allow disk storage to be allocated at different levels of granularity. For instance, a file system could allocate 4 KB of disk space as a single 4-KB block or as eight 512-byte blocks. How could we take advantage of this flexibility to improve performance? What modifications would have to be made to the free-space management scheme in order to support this feature?

14.12 Discuss how performance optimizations for file systemsmight result in difficulties in maintaining the consistency of the systems in the event of computer crashes.

14.13 Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of supporting links to files that cross mount points (that is, the file link refers to a file that is stored in a different volume).

14.14 Consider a file system on a disk that has both logical and physical block sizes of 512 bytes. Assume that the information about each file is already in memory. For each of the three allocation strategies (con- tiguous, linked, and indexed), answer these questions:

EX-49

Exercises

a. How is the logical-to-physical address mapping accomplished in this system? (For the indexed allocation, assume that a file is always less than 512 blocks long.)

b. If we are currently at logical block 10 (the last block accessed was block 10) and want to access logical block 4, how many physical blocks must be read from the disk?

14.15 Consider a file system that uses inodes to represent files. Disk blocks are 8 KB in size, and a pointer to a disk block requires 4 bytes. This file system has 12 direct disk blocks, as well as single, double, and triple indirect disk blocks. What is the maximum size of a file that can be stored in this file system?

14.16 Fragmentation on a storage device can be eliminated through com- paction. Typical disk devices do not have relocation or base registers (such as those used when memory is to be compacted), so how can we relocate files? Give three reasons why compacting and relocating files are often avoided.

14.17 Explain why logging metadata updates ensures recovery of a file sys- tem after a file-system crash.

14.18 Consider the following backup scheme:

• Day 1. Copy to a backup medium all files from the disk.

• Day 2. Copy to another medium all files changed since day 1.

• Day 3. Copy to another medium all files changed since day 1.

This differs from the schedule given in Section 14.7.4 by having all subsequent backups copy all files modified since the first full backup. What are the benefits of this system over the one in Section 14.7.4? What are the drawbacks? Are restore operations made easier or more difficult? Explain your answer.

14.19 Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of associating with remote file systems (stored on file servers) a set of failure semantics different from those associated with local file systems.

14.20 What are the implications of supporting UNIX consistency semantics for shared access to files stored on remote file systems?

EX-50