Building Blocks

Although the virtual machine concept is useful, it is difficult to implement. Much work is required to provide an exact duplicate of the underlying machine. This is especially a challenge on dual-mode systems, where the underlying machine has only user mode and kernel mode. In this section, we examine the building blocks that are needed for efficient virtualization. Note that these building blocks are not required by type 0 hypervisors, as discussed in Section 18.5.2.

The ability to virtualize depends on the features provided by the CPU. If the features are sufficient, then it is possible to write a VMM that provides a guest environment. Otherwise, virtualization is impossible. VMMs use sev- eral techniques to implement virtualization, including trap-and-emulate and binary translation. We discuss each of these techniques in this section, along with the hardware support needed to support virtualization.

As you read the section, keep in mind that an important concept found in most virtualization options is the implementation of a virtual CPU (VCPU). The VCPU does not execute code. Rather, it represents the state of the CPU as the guest machine believes it to be. For each guest, the VMM maintains a VCPU representing that guest’s current CPU state.When the guest is context-switched onto a CPU by the VMM, information from the VCPU is used to load the right context, much as a general-purpose operating system would use the PCB.

Trap-and-Emulate

On a typical dual-mode system, the virtual machine guest can execute only in user mode (unless extra hardware support is provided). The kernel, of course, runs in kernel mode, and it is not safe to allow user-level code to run in kernel mode. Just as the physical machine has two modes, so must the virtual machine. Consequently, wemust have a virtual user mode and a virtual kernel mode, both of which run in physical user mode. Those actions that cause a transfer from user mode to kernel mode on a real machine (such as a system call, an interrupt, or an attempt to execute a privileged instruction) must also cause a transfer from virtual user mode to virtual kernel mode in the virtual machine.

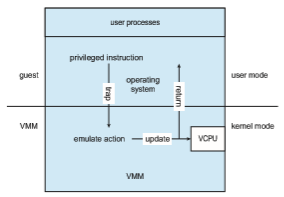

How can such a transfer be accomplished? The procedure is as follows: When the kernel in the guest attempts to execute a privileged instruction, that is an error (because the system is in user mode) and causes a trap to the VMM in the real machine. The VMM gains control and executes (or “emulates”) the action that was attempted by the guest kernel on the part of the guest. It

then returns control to the virtual machine. This is called the trap-and-emulate method and is shown in Figure 18.2.

With privileged instructions, time becomes an issue. All nonprivileged instructions run natively on the hardware, providing the same performance for guests as native applications. Privileged instructions create extra overhead, however, causing the guest to run more slowly than it would natively. In addition, the CPU is being multiprogrammed among many virtual machines, which can further slow down the virtual machines in unpredictable ways.

This problem has been approached in various ways. IBM VM, for exam- ple, allows normal instructions for the virtual machines to execute directly on the hardware. Only the privileged instructions (needed mainly for I/O) must be emulated and hence execute more slowly. In general, with the evolu- tion of hardware, the performance of trap-and-emulate functionality has been improved, and cases in which it is needed have been reduced. For example, many CPUs now have extra modes added to their standard dual-mode opera- tion. The VCPU need not keep track of what mode the guest operating system is in, because the physical CPU performs that function. In fact, some CPUs provide guest CPU state management in hardware, so the VMM need not supply that functionality, removing the extra overhead.

Some CPUs do not have a clean separation of privileged and nonprivileged instructions. Unfortunately for virtualization implementers, the Intel x86 CPU line is one of them. No thought was given to running virtualization on the x86 when it was designed. (In fact, the first CPU in the family—the Intel 4004, released in 1971—was designed to be the core of a calculator.) The chip has maintained backward compatibility throughout its lifetime, preventing changes that would have made virtualization easier through many generations.

Let’s consider an example of the problem. The command popf loads the flag register from the contents of the stack. If the CPU is in privileged mode, all of the flags are replaced from the stack. If the CPU is in user mode, then only some flags are replaced, and others are ignored. Because no trap is generated if popf is executed in user mode, the trap-and-emulate procedure is rendered useless. Other x86 instructions cause similar problems. For the purposes of this discussion, we will call this set of instructions special instructions. As recently as 1998, using the trap-and-emulatemethod to implement virtualization on the x86 was considered impossible because of these special instructions.

This previously insurmountable problem was solved with the implemen- tation of the binary translation technique. Binary translation is fairly simple in concept but complex in implementation. The basic steps are as follows:

1. If the guest VCPU is in user mode, the guest can run its instructions natively on a physical CPU.

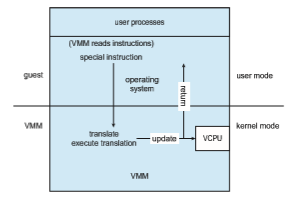

2. If the guest VCPU is in kernel mode, then the guest believes that it is run- ning in kernel mode. The VMM examines every instruction the guest exe- cutes in virtual kernel mode by reading the next few instructions that the guest is going to execute, based on the guest’s program counter. Instruc- tions other than special instructions are run natively. Special instructions are translated into a new set of instructions that perform the equivalent task—for example, changing the flags in the VCPU.

Binary translation is shown in Figure 18.3. It is implemented by translation code within the VMM. The code reads native binary instructions dynamically from the guest, on demand, and generates native binary code that executes in place of the original code.

The basic method of binary translation just described would execute correctly but perform poorly. Fortunately, the vast majority of instructions would execute natively. But how could performance be improved for the other instructions? We can turn to a specific implementation of binary translation, the VMware method, to see one way of improving performance. Here, caching provides the solution. The replacement code for each instruction that needs to be translated is cached. All later executions of that instruction run from the translation cache and need not be translated again. If the cache is large enough, this method can greatly improve performance.

Let’s consider another issue in virtualization: memory management, specifically the page tables. How can the VMM keep page-table state both for guests that believe they are managing the page tables and for the VMM itself? A common method, used with both trap-and-emulate and binary translation, is to use nested page tables (NPTs). Each guest operating system maintains one or more page tables to translate from virtual to physical memory. The VMM maintains NPTs to represent the guest’s page-table state, just as it creates a VCPU to represent the guest’s CPU state. The VMM knows when the guest tries to change its page table, and it makes the equivalent change in the NPT. When the guest is on the CPU, the VMM puts the pointer to the appropriate NPT into the appropriate CPU register to make that table the active page table. If the guest needs to modify the page table (for example, fulfilling a page fault), then that operation must be intercepted by the VMM and appropriate changes made to the nested and system page tables. Unfortunately, the use of NPTs can cause TLB misses to increase, and many other complexities need to be addressed to achieve reasonable performance.

Although it might seem that the binary translation method creates large amounts of overhead, it performed well enough to launch a new industry aimed at virtualizing Intel x86-based systems. VMware tested the performance impact of binary translation by booting one such system, Windows XP, and immediately shutting it down while monitoring the elapsed time and the number of translations produced by the binary translation method. The result was 950,000 translations, taking 3 microseconds each, for a total increase of 3 seconds (about 5 percent) over native execution of Windows XP. To achieve that result, developers used many performance improvements that we do not discuss here. Formore information, consult the bibliographical notes at the end of this chapter.