Distributed File Systems

Although the World Wide Web is the predominant distributed system in use today, it is not the only one. Another important and popular use of distributed computing is the distributed fil system, or DFS.

To explain the structure of a DFS, we need to define the terms service, server, and client in the DFS context. A service is a software entity running on one or more machines and providing a particular type of function to clients. A server is the service software running on a single machine. A client is a process that can invoke a service using a set of operations that form its client interface. Sometimes a lower-level interface is defined for the actual cross- machine interaction; it is the intermachine interface.

Using this terminology, we say that a file system provides file services to clients. A client interface for a file service is formed by a set of primitive file operations, such as create a file, delete a file, read from a file, and write to a file. The primary hardware component that a file server controls is a set of local secondary-storage devices (usually, hard disks or solid-state drives) on which files are stored and from which they are retrieved according to the clients’ requests.

A DFS is a file system whose clients, servers, and storage devices are dis- persed among themachines of a distributed system. Accordingly, service activ- ity has to be carried out across the network. Instead of a single centralized data repository, the system frequently has multiple and independent storage devices. As you will see, the concrete configuration and implementation of a DFS may vary from system to system. In some configurations, servers run on dedicated machines. In others, a machine can be both a server and a client.

The distinctive features of a DFS are the multiplicity and autonomy of clients and servers in the system. Ideally, though, a DFS should appear to its clients to be a conventional, centralized file system. That is, the client interface

of a DFS should not distinguish between local and remote files. It is up to the DFS to locate the files and to arrange for the transport of the data. A transparent DFS—like the transparent distributed systems mentioned earlier—facilitates user mobility by bringing a user’s environment (for example, the user’s home directory) to wherever the user logs in.

The most important performance measure of a DFS is the amount of time needed to satisfy service requests. In conventional systems, this time consists of storage-access time and a small amount of CPU-processing time. In a DFS, however, a remote access has the additional overhead associated with the distributed structure. This overhead includes the time to deliver the request to a server, as well as the time to get the response across the network back to the client. For each direction, in addition to the transfer of the information, there is the CPU overhead of running the communication protocol software. The performance of a DFS can be viewed as another dimension of the DFS’s transparency. That is, the performance of an ideal DFS would be comparable to that of a conventional file system.

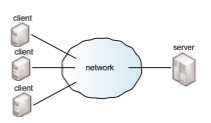

The basic architecture of a DFS depends on its ultimate goals. Two widely used architectural models we discuss here are the client–server model and the cluster-based model. The main goal of a client–server architecture is to allow transparent file sharing among one or more clients as if the files were stored locally on the individual client machines. The distributed file systems NFS and OpenAFS are prime examples. NFS is the most common UNIX-based DFS. It has several versions, and here we refer to NFS Version 3 unless otherwise noted.

If many applications need to be run in parallel on large data sets with high availability and scalability, the cluster-based model is more appropriate than the client–server model. Two well-known examples are the Google file system and the open-source HDFS, which runs as part of the Hadoop framework.

The Client–Server DFS Model

Figure 19.12 illustrates a simple DFS client–server model. The server stores both files and metadata on attached storage. In some systems, more than one server can be used to store different files. Clients are connected to the server through a network and can request access to files in the DFS by contacting the server through a well-known protocol such as NFS Version 3.

is responsible for carrying out authentication, checking the requested file per- missions, and, if warranted, delivering the file to the requesting client. When a clientmakes changes to the file, the clientmust somehowdeliver those changes to the server (which holds the master copy of the file). The client’s and the server’s versions of the file should be kept consistent in a way that minimizes network traffic and the server’s workload to the extent possible.

The network file system (NFS) protocol was originally developed by Sun Microsystems as an open protocol, which encouraged early adoption across different architectures and systems. From the beginning, the focus of NFS was simple and fast crash recovery in the face of server failure. To implement this goal, the NFS server was designed to be stateless; it does not keep track of which client is accessing which file or of things such as open file descriptors and file pointers. This means that, whenever a client issues a file operation (say, to read a file), that operation has to be idempotent in the face of server crashes. Idempotent describes an operation that can be issued more than once yet return the same result. In the case of a read operation, the client keeps track of the state (such as the file pointer) and can simply reissue the operation if the server has crashed and come back online. You can readmore about the NFS implementation in Section 15.8.

The Andrew fil system (OpenAFS) was created at Carnegie Mellon Uni- versitywith a focus on scalability. Specifically, the researcherswanted to design a protocol that would allow the server to support as many clients as possible. Thismeantminimizing requests and traffic to the server.When a client requests a file, the file’s contents are downloaded from the server and stored on the client’s local storage. Updates to the file are sent to the server when the file is closed, and new versions of the file are sent to the clientwhen the file is opened. In comparison, NFS is quite chatty and will send block read and write requests to the server as the file is being used by a client.

Both OpenAFS and NFS are meant to be used in addition to local file sys- tems. In other words, youwould not format a hard drive partitionwith the NFS file system. Instead, on the server, you would format the partition with a local file system of your choosing, such as ext4, and export the shared directories via the DFS. In the client, you would simply attach the exported directories to your file-system tree. In this way, the DFS can be separated from responsibility for the local file system and can concentrate on distributed tasks.

The DFS client–server model, by design, may suffer from a single point of failure if the server crashes. Computer clustering can help resolve this problem by using redundant components and clustering methods such that failures are detected and failing over to working components continues server operations. In addition, the server presents a bottleneck for all requests for both data and metadata, which results in problems of scalability and bandwidth.

The Cluster-Based DFS Model

As the amount of data, I/Oworkload, and processing expands, so does the need for a DFS to be fault-tolerant and scalable. Large bottlenecks cannot be tolerated, and system component failures must be expected. Cluster-based architecture was developed in part to meet these needs.

Figure 19.13 illustrates a sample cluster-based DFS model. This is the basic model presented by the Google file system (GFS) and the Hadoop distributed

fil system (HDFS). One or more clients are connected via a network to a master metadata server and several data servers that house “chunks” (or por- tions) of files. The metadata server keeps a mapping of which data servers hold chunks of which files, as well as a traditional hierarchical mapping of directories and files. Each file chunk is stored on a data server and is replicated a certain number of times (for example, three times) to protect against compo- nent failure and for faster access to the data (servers containing the replicated chunks have fast access to those chunks).

To obtain access to a file, a client must first contact the metadata server. The metadata server then returns to the client the identities of the data servers that hold the requested file chunks. The client can then contact the closest data server (or servers) to receive the file information. Different chunks of the file can be read or written to in parallel if they are stored on different data servers, and the metadata server may need to be contacted only once in the entire process. This makes the metadata server less likely to be a performance bottleneck. The metadata server is also responsible for redistributing and balancing the file chunks among the data servers.

GFS was released in 2003 to support large distributed data-intensive appli- cations. The design of GFS was influenced by four main observations:

• Hardware component failures are the norm rather than the exception and should be routinely expected.

• Files stored on such a system are very large.

• Most files are changed by appending new data to the end of the file rather than overwriting existing data.

• Redesigning the applications and file system API increases the system’s flexibility.

Consistent with the fourth observation, GFS exports its own API and requires applications to be programmed with this API.

Shortly after developing GFS, Google developed a modularized software layer called MapReduce to sit on top of GFS. MapReduce allows developers to carry out large-scale parallel computations more easily and utilizes the benefits of the lower-layer file system. Later, HDFS and the Hadoop framework (which includes stackable modules like MapReduce on top of HDFS) were created based on Google’s work. Like GFS and MapReduce, Hadoop supports the processing of large data sets in distributed computing environments. As suggested earlier, the drive for such a framework occurred because traditional systems could not scale to the capacity and performance needed by “big data” projects (at least not at reasonable prices). Examples of big data projects include crawling and analyzing social media, customer data, and large amounts of scientific data points for trends.