Summary

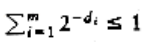

We have seen uses of trees in operating systems, compiler design, and searching. Expression trees are a small example of a more general structure known as a parse tree, which is a central data structure in compiler design. Parse trees are not binary, but are relatively simple extensions of expression trees (although the algorithms to build them are not quite so simple).

Search trees are of great importance in algorithm design. They support almost all the useful operations, and the logarithmic average cost is very small. Nonrecursive implementations of search trees are somewhat faster, but the recursive versions are sleeker, more elegant, and easier to understand and debug. The problem with search trees is that their performance depends heavily on the input being random. If this is not the case, the running time increases significantly, to the point where search trees become expensive linked lists.

We saw several ways to deal with this problem. AVL trees work by insisting that all nodes’ left and right subtrees differ in heights by at most one. This ensures that the tree cannot get too deep. The operations that do not change the tree, as insertion does, can all use the standard binary search tree code. Operations that change the tree must restore the tree. This can be somewhat complicated, especially in the case of deletion. We showed how to restore the tree after insertions in O(log n) time.

We also examined the splay tree. Nodes in splay trees can get arbitrarily deep, but after every access the tree is adjusted in a somewhat mysterious manner. The net effect is that any sequence of m operations takes O(m log n) time, which is the same as a balanced tree would take.

B-trees are balanced m-way (as opposed to 2-way or binary) trees, which are well suited for disks; a special case is the 2-3 tree, which is another common method of implementing balanced search trees.

In practice, the running time of all the balanced tree schemes is worse (by a constant factor) than the simple binary search tree, but this is generally acceptable in view of the protection being given against easily obtained worst- case input.

A final note: By inserting elements into a search tree and then performing an inorder traversal, we obtain the elements in sorted order. This gives an O(n log n) algorithm to sort, which is a worst-case bound if any sophisticated search tree is used. We shall see better ways in Chapter 7, but none that have a lower time bound.

Exercises

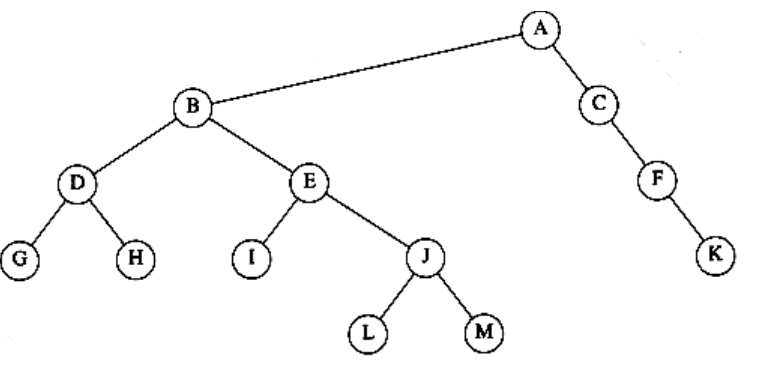

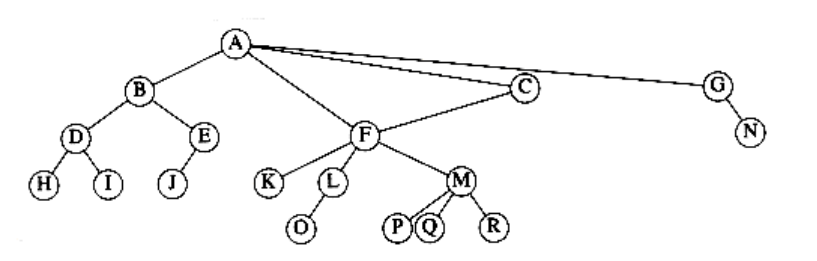

Questions 4.1 to 4.3 refer to the tree in Figure 4.63.

4.1 For the tree in Figure 4.63 :

a. Which node is the root?

b. Which nodes are leaves?

Figure 4.63

4.2 For each node in the tree of Figure 4.63 :

a. Name the parent node.

b. List the children.

c. List the siblings.

d. Compute the depth.

e. Compute the height.

4.3 What is the depth of the tree in Figure 4.63?

4.4 Show that in a binary tree of n nodes, there are n + 1 pointers representing children.

4.5 Show that the maximum number of nodes in a binary tree of height h is 2h+1 - 1.

4.6 A full node is a node with two children. Prove that the number of full nodes plus one is equal to the number of leaves in a binary tree.

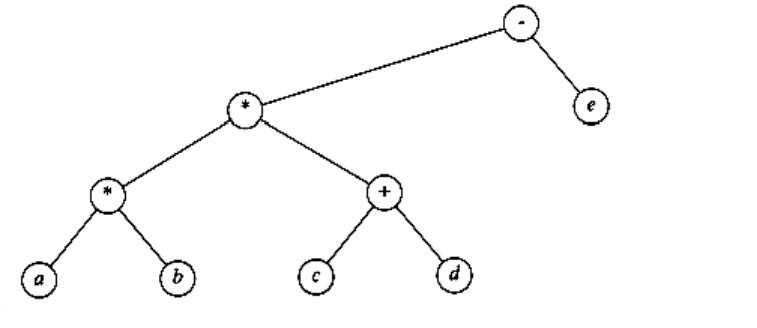

4.7 Suppose a binary tree has leaves l1, l2, . . . , lm at depth d1, d2, . . . ,

dm, respectively. Prove that

4.8 Give the prefix, infix, and postfix expressions corresponding to the tree in Figure 4.64.

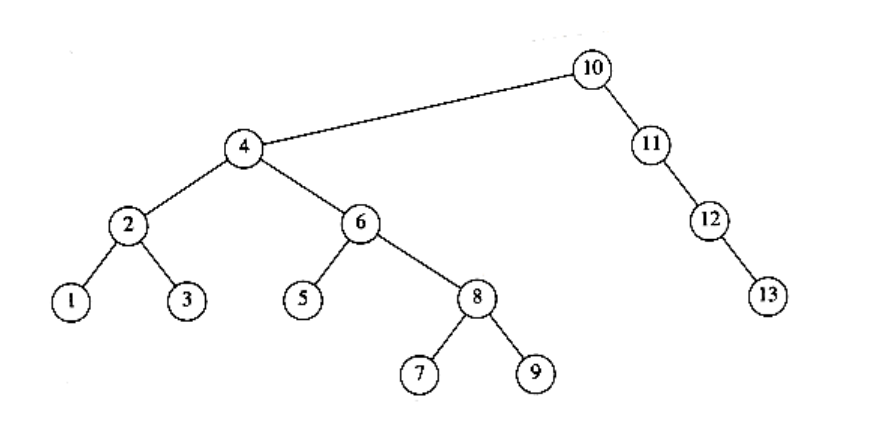

4.9 a. Show the result of inserting 3, 1, 4, 6, 9, 2, 5, 7 into an initially empty binary search tree.

b. Show the result of deleting the root.

4.10 Write routines to implement the basic binary search tree operations.

4.11 Binary search trees can be implemented with cursors, using a strategy similar to a cursor linked list implementation. Write the basic binary search tree routines using a cursor implementation.

4.12 Suppose you want to perform an experiment to verify the problems that can be caused by random insert/delete pairs. Here is a strategy that is not perfectlyrandom, but close enough. You build a tree with n elements by inserting

n elements chosen at random from the range 1 to m = n. You then perform n2 pairs of insertions followed by deletions. Assume the existence of a routine, rand_int(a,b), which returns a uniform random integer between a and b inclusive.

Figure 4.64 Tree for Exercise 4.8

a. Explain how to generate a random integer between 1 and m that is not already in the tree (so a random insert can be performed). In terms of n and , what is the running time of this operation?

b. Explain how to generate a random integer between 1 and m that is already in the tree (so a random delete can be performed). What is the running time of this operation?

c. What is a good choice of ? Why?

4.13 Write a program to evaluate empirically the following strategies for deleting nodes with two children:

a. Replace with the largest node, X, in TL and recursively delete X.

b. Alternately replace with the largest node in TL and the smallest node in TR,and recursively delete appropriate node.

c. Replace with either the largest node in TL or the smallest node in TR (recursively deleting the appropriate node), making the choice randomly. Which strategy seems to give the most balance? Which takes the least CPU time to process the entire sequence?

4.14 ** Prove that the depth of a random binary search tree (depth of the deepest node) is O(log n), on average.

4.15 *a. Give a precise expression for the minimum number of nodes in an AVL tree of height h.

b. What is the minimum number of nodes in an AVL tree of height 15?

4.16 Show the result of inserting 2, 1, 4, 5, 9, 3, 6, 7 into an initially empty AVL tree.

4.17 * Keys 1, 2, . . . , 2k -1 are inserted in order into an initially empty AVL tree. Prove that the resulting tree is perfectly balanced.

4.18 Write the remaining procedures to implement AVL single and double rotations.

4.19 Write a nonrecursive function to insert into an AVL tree.

4.20 * How can you implement (nonlazy) deletion in AVL trees?

4.21 a. How many bits are required per node to store the height of a node in an n-node AVL tree?

b. What is the smallest AVL tree that overflows an 8-bit height counter?

4.22 Write the functions to perform the double rotation without the inefficiency of doing two single rotations.

4.23 Show the result of accessing the keys 3, 9, 1, 5 in order in the splay tree in Figure 4.65.

Figure 4.65

4.24 Show the result of deleting the element with key 6 in the resulting splay tree for the previous exercise.

4.25 Nodes 1 through n = 1024 form a splay tree of left children.

a. What is the internal path length of the tree (exactly)?

*b. Calculate the internal path length after each of find(1), find(2), find(3), find(4), find(5), find(6).

*c. If the sequence of successive finds is continued, when is the internal path length minimized?

4.26 a. Show that if all nodes in a splay tree are accessed in sequential order, the resulting tree consists of a chain of left children.

**b. Show that if all nodes in a splay tree are accessed in sequential order, then the total access time is O(n), regardless of the initial tree.

4.27 Write a program to perform random operations on splay trees. Count the total number of rotations performed over the sequence. How does the running time compare to AVL trees and unbalanced binary search trees?

4.28 Write efficient functions that take only a pointer to a binary tree, T, and compute

a. the number of nodes in T

b. the number of leaves in T

c. the number of full nodes in T

What is the running time of your routines?

4.29 Write a function to generate an n-node random binary search tree with distinct keys 1 through n. What is the running time of your routine?

4.30 Write a function to generate the AVL tree of height h with fewest nodes. What is the running time of your function?

4.31 Write a function to generate a perfectly balanced binary search tree of height h with keys 1 through 2h+1 - 1. What is the running time of your function?

4.32 Write a function that takes as input a binary search tree, T, and two keys k1 and k2, which are ordered so that k1 k2, and prints all elements x in the tree such that k1 key(x) k2. Do not assume any information about the type of keys except that they can be ordered (consistently). Your program should run in O(K + log n) average time, where K is the number of keys printed. Bound the running time of your algorithm.

4.33 The larger binary trees in this chapter were generated automatically by a program. This was done by assigning an (x, y) coordinate to each tree node, drawing a circle around each coordinate (this is hard to see in some pictures), and connecting each node to its parent. Assume you have a binary search tree stored in memory (perhaps generated by one of the routines above) and that each node has two extra fields to store the coordinates.

a. The x coordinate can be computed by assigning the inorder traversal number. Write a routine to do this for each node in the tree.

b. The y coordinate can be computed by using the negative of the depth of the node. Write a routine to do this for each node in the tree.

c. In terms of some imaginary unit, what will the dimensions of the picture be? How can you adjust the units so that the tree is always roughly two-thirds as high as it is wide?

d. Prove that using this system no lines cross, and that for any node, X, all elements in X’s left subtree appear to the left of X and all elements in X’s right subtree appear to the right of X.

4.34 Write a general-purpose tdrawing program that will convert a tree into the following graph-assembler instructions:

a. circle(x, y)

b. drawline(i, j)

The first instruction draws a circle at (x, y), and the second instruction connects the ith circle to the jth circle (circles are numbered in the order drawn). You should either make this a program and define some sort of input language or make this a function that can be called from any program. What is the running time of your routine?

4.35 Write a routine to list out the nodes of a binary tree in level-order. List the root, then nodes at depth 1, followed by nodes at depth 2, and so on. You must do this in linear time. Prove your time bound.4.36

a. Show the result of inserting the following keys into an initially empty 2-3 tree: 3, 1, 4, 5, 9, 2, 6, 8, 7, 0.

b. Show the result of deleting 0 and then 9 from the 2-3 tree created in part (a).

4.37 *a. Write a routine to perform insertion from a B-tree.

*b. Write a routine to perform deletion from a B-tree. When a key is deleted, is it necessary to update information in the internal nodes?

Figure 4.66 Tree for Exercise 4.39

*c. Modify your insertion routine so that if an attempt is made to add into a node that already has m entries, a search is performed for a sibling with less than m children before the node is split.

4.38 A B*-tree of order m is a B-tree in which each each interior node has between 2m/3 and m children. Describe a method to perform insertion into a B*- tree.

4.39 Show how the tree in Figure 4.66 is represented using a child/sibling pointer implementation.

4.40 Write a procedure to traverse a tree stored with child/sibling links.

4.41 Two binary trees are similar if they are both empty or both nonempty and have similar left and right subtrees. Write a function to decide whether two binary trees are similar. What is the running time of your program?

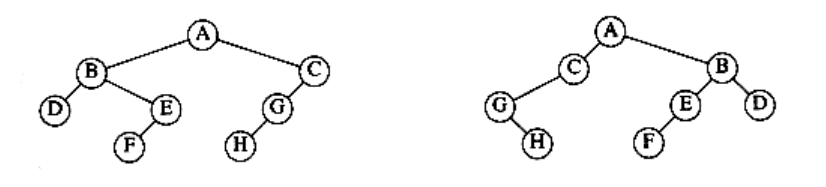

4.42 Two trees, T1 and T2, are isomorphic if T1 can be transformed into T2 by swapping left and right children of (some of the) nodes in T1. For instance, the two trees in Figure 4.67 are isomorphic because they are the same if the children of A, B, and G, but not the other nodes, are swapped.

a. Give a polynomial time algorithm to decide if two trees are isomorphic.

*b. What is the running time of your program (there is a linear solution)?

4.43 *a. Show that via AVL single rotations, any binary search tree T1 can be transformed into another search tree T2 (with the same keys).

*b. Give an algorithm to perform this transformation using O(n log n) rotations on average.

**c. Show that this transformation can be done with O(n) rotations, worst-case.

Figure 4.67 Two isomorphic trees

4.44 Suppose we want to add the operation find_kth to our repertoire. The

operation find_kth(T,i) returns the element in tree T with ith smallest key. Assume all elements have distinct keys. Explain how to modify the binary search tree to support this operation in O(log n) average time, without sacrificing the time bounds of any other operation.

4.45 Since a binary search tree with n nodes has n + 1 pointers, half the space allocated in a binary search tree for pointer information is wasted. Suppose that if a node has a left child, we make its left child point to its inorder predecessor, and if a node has a right child, we make its right child point to its inorder successor. This is known as a threaded tree and the extra pointers are called threads.

a. How can we distinguish threads from real children pointers?

b. Write routines to perform insertion and deletion into a tree threaded in the manner described above.

c. What is the advantage of using threaded trees?

4.46 A binary search tree presupposes that searching is based on only one key per record. Suppose we would like to be able to perform searching based on either of two keys, key1 or key2.

a. One method is to build two separate binary search trees. How many extra pointers does this require?

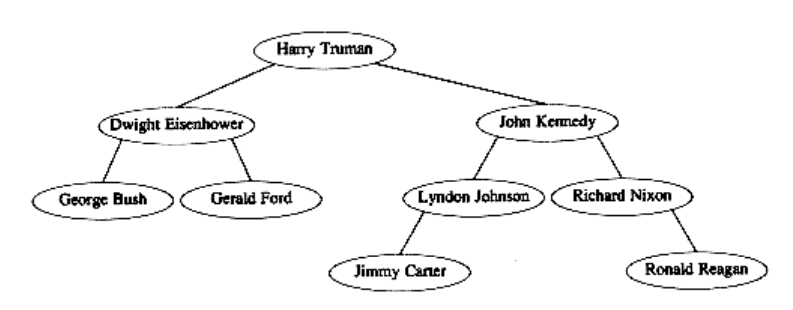

b. An alternative method is a 2-d tree. A 2-d tree is similar to a binary search tree, except that branching at even levels is done with respect to key1, and branching at odd levels is done with key2. Figure 4.68 shows a 2-d tree, with the first and last names as keys, for post-WWII presidents. The presidents’ names were inserted chronologically (Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, Bush). Write a routine to perform insertion into a 2-d tree.

c. Write an efficient procedure that prints all records in the tree thatsimultaneously satisfy the constraints low1 key1 high1 and low2 key2 high2.

d. Show how to extend the 2-d tree to handle more than two search keys. The resulting strategy is known as a k-d tree.

Figure 4.68 A 2-d tree

References

More information on binary search trees, and in particular the mathematical properties of trees can be found in the two books by Knuth [23] and [24].

Several papers deal with the lack of balance caused by biased deletion algorithms in binary search trees. Hibbard’s paper [20] proposed the original deletion algorithm and established that one deletion preserves the randomness of the trees. A complete analysis has been performed only for trees with three [21] and four nodes[5]. Eppinger’s paper [15] provided early empirical evidence of nonrandomness, and the papers by Culberson and Munro, [11], [12], provide some analytical evidence (but not a complete proof for the general case of intermixed insertions and deletions).

AVL trees were proposed by Adelson-Velskii and Landis [1]. Simulation results for AVL trees, and variants in which the height imbalance is allowed to be at most k for various values of k, are presented in [22]. A deletion algorithm for AVL trees can be found in [24]. Analysis of the averaged depth of AVL trees is incomplete, but some results are contained in [25].

[3] and [9] considered self-adjusting trees like the type in Section 4.5.1. Splay trees are described in [29].

B-trees first appeared in [6]. The implementation described in the original paper allows data to be stored in internal nodes as well as leaves. The data structure we have described is sometimes known as a B+ tree. A survey of the different types of B-trees is presented in [10]. Empirical results of the various schemes is reported in [18]. Analysis of 2-3 trees and B-trees can be found in [4], [14], and [33].

Exercise 4.14 is deceptively difficult. A solution can be found in [16]. Exercise 4.26 is from [32]. Information on B*-trees, described in Exercise 4.38, can be found in [13]. Exercise 4.42 is from [2]. A solution to Exercise 4.43 using 2n -6 rotations is given in [30]. Using threads, a la Exercise 4.45, was first proposed in [28]. k-d trees were first proposed in [7]. Their major drawback is that both deletion and balancing are difficult. [8] discusses k-d trees and other methods used for multidimensional searching.

Other popular balanced search trees are red-black trees [19] and weight-balanced trees [27]. More balanced tree schemes can be found in the books [17], [26], and [31].

-

G. M. Adelson-Velskii and E. M. Landis, “An Algorithm for the Organization of Information,” Soviet Math. Doklady 3 (1962), 1259-1263.

-

A. V. Aho, J. E. Hopcroft, and J. D. Ullman, The Design and Analysis of Computer Algorithms, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1974.

-

B. Allen and J. I. Munro, “Self Organizing Search Trees,” Journal of the ACM, 25 (1978), 526-535.

-

R. A. Baeza-Yates, “Expected Behaviour of B+- trees under Random Insertions,” Acta Informatica 26 (1989), 439-471.

-

R. A. Baeza-Yates, “A Trivial Algorithm Whose Analysis Isn’t: A Continuation,” BIT 29 (1989), 88-113.

-

R. Bayer and E. M. McGreight, “Organization and Maintenance of Large Ordered Indices,” Acta Informatica 1 (1972), 173-189.

-

J. L. Bentley, “Multidimensional Binary Search Trees Used for Associative Searching,” Communications of the ACM 18 (1975), 509-517.

-

J. L. Bentley and J. H. Friedman, “Data Structures for Range Searching,” Computing Surveys 11 (1979), 397-409.

-

J. R. Bitner, “Heuristics that Dynamically Organize Data Structures,” SIAM Journal on Computing 8 (1979), 82-110.

-

D. Comer, “The Ubiquitous B-tree,” Computing Surveys 11 (1979), 121-137.

-

J. Culberson and J. I. Munro, “Explaining the Behavior of Binary Search Trees under Prolonged Updates: A Model and Simulations,” Computer Journal 32 (1989), 68-75.

-

J. Culberson and J. I. Munro, “Analysis of the Standard Deletion Algorithms’ in Exact Fit Domain Binary Search Trees,” Algorithmica 5 (1990) 295-311.

-

K. Culik, T. Ottman, and D. Wood, “Dense Multiway Trees,” ACM Transactions on Database Systems 6 (1981), 486-512.

-

B. Eisenbath, N. Ziviana, G. H. Gonnet, K. Melhorn, and D. Wood, “The Theoryof Fringe Analysis and its Application to 2-3 Trees and B-trees,” Information and Control 55 (1982), 125-174.

-

J. L. Eppinger, “An Empirical Study of Insertion and Deletion in Binary Search Trees,” Communications of the ACM 26 (1983), 663-669.

-

P. Flajolet and A. Odlyzko, “The Average Height of Binary Trees and Other Simple Trees,” Journal of Computer and System Sciences 25 (1982), 171-213.

-

G. H. Gonnet and R. Baeza-Yates, Handbook of Algorithms and Data Structures, second edition, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1991.

-

E. Gudes and S. Tsur, “Experiments with B-tree Reorganization,” Proceedings of ACM SIGMOD Symposium on Management of Data (1980), 200-206.

-

L. J. Guibas and R. Sedgewick, “A Dichromatic Framework for Balanced Trees,” Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (1978), 8-21.

-

T. H. Hibbard, “Some Combinatorial Properties of Certain Trees with Applications to Searching and Sorting,” Journal of the ACM 9 (1962), 13-28.

-

A. T. Jonassen and D. E. Knuth, “A Trivial Algorithm Whose Analysis Isn’t,” Journal of Computer and System Sciences 16 (1978), 301-322.

-

P. L. Karlton, S. H. Fuller, R. E. Scroggs, and E. B. Kaehler, “Performance of Height Balanced Trees,” Communications of the ACM 19 (1976), 23-28.

-

D. E. Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming: Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms, second edition, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1973.

-

D. E. Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming: Volume 3: Sorting and Searching, second printing, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1975.

-

K. Melhorn, “A Partial Analysis of Height-Balanced Trees under Random Insertions and Deletions,” SIAM Journal of Computing 11 (1982), 748-760.

-

K. Melhorn, Data Structures and Algorithms 1: Sorting and Searching, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1984.

-

J. Nievergelt and E. M. Reingold, “Binary Search Trees of Bounded Balance,” SIAM Journal on Computing 2 (1973), 33-43.

-

A. J. Perlis and C. Thornton, “Symbol Manipulation in Threaded Lists,” Communications of the ACM 3 (1960), 195-204.

-

D. D. Sleator and R. E. Tarjan, “Self-adjusting Binary Search Trees,” Journal of ACM 32 (1985), 652-686.

-

D. D. Sleator, R. E. Tarjan, and W. P. Thurston, “Rotation Distance, Triangulations, and Hyperbolic Geometry,” Journal of AMS (1988), 647-682.31. H. F. Smith, Data Structures-Form and Function, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987.

-

R. E. Tarjan, “Sequential Access in Splay Trees Takes Linear Time,” Combinatorica 5 (1985), 367-378.

-

A. C. Yao, “On Random 2-3 trees,” Acta Informatica 9 (1978), 159-170.