AVL Trees

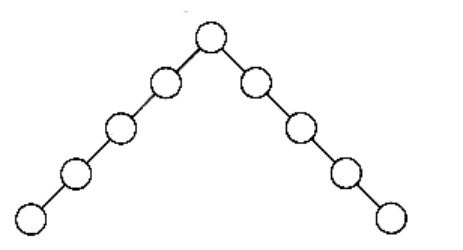

An AVL (Adelson-Velskii and Landis) tree is a binary search tree with a balance condition. The balance condition must be easy to maintain, and it ensures that the depth of the tree is O(log n). The simplest idea is to require that the left and right subtrees have the same height. As Figure 4.28 shows, this idea does not force the tree to be shallow.

Figure 4.28 A bad binary tree. Requiring balance at the root is not enough.

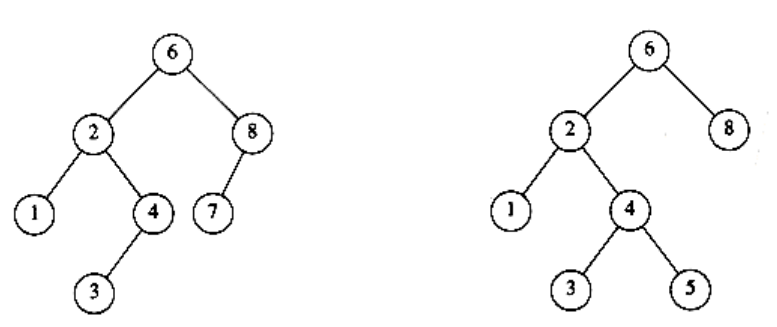

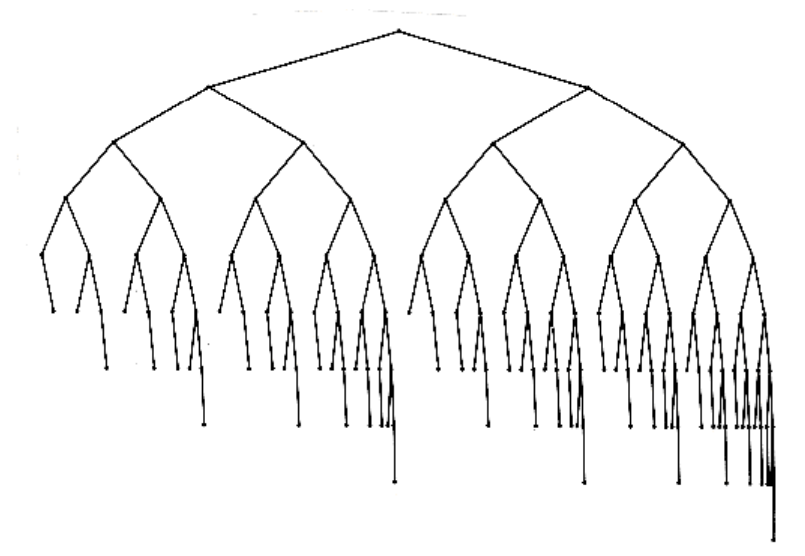

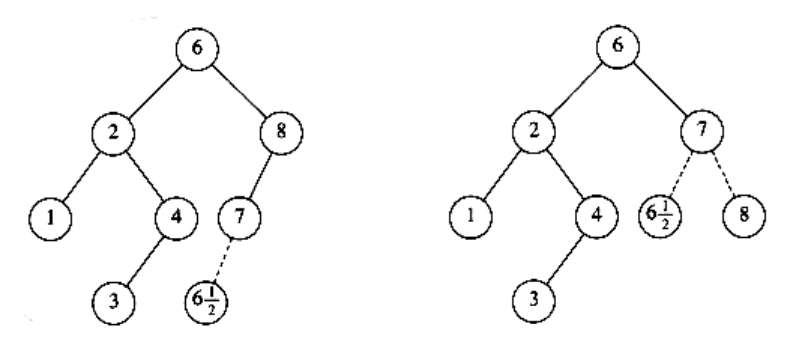

Another balance condition would insist that every node must have left and right subtrees of the same height. If the height of an empty subtree is defined to be -1 (as is usual), then only perfectly balanced trees of 2k - 1 nodes would satisfy this criterion. Thus, although this guarantees trees of small depth, the balance condition is too rigid to be useful and needs to be relaxed.An AVL tree is identical to a binary search tree, except that for every node in the tree, the height of the left and right subtrees can differ by at most 1. (The height of an empty tree is defined to be -1.) In Figure 4.29 the tree on the left is an AVL tree, but the tree on the right is not. Height information is kept for each node (in the node structure). It is easy to show that the height of an AVL tree is at most roughly 1.44 log(n + 2) - .328, but in practice it is about log(n + 1) + 0.25 (although the latter claim has not been proven). As an example, the AVL tree of height 9 with the fewest nodes (143) is shown in Figure 4.30. This tree has as a left subtree an AVL tree of height 7 of minimum size. The right subtree is an AVL tree of height 8 of minimum size. This tells us that the minimum number of nodes, N(h), in an AVL tree of height h is given by N(h) = N(h -1) + N(h - 2) + 1. For h = 0, N(h) = 1. For h = 1, N(h) = 2. The function N(h) is closely related to the Fibonacci numbers, from which the bound claimed above on the height of an AVL tree follows.

Thus, all the tree operations can be performed in O(log n) time, except possibly insertion (we will assume lazy deletion). When we do an insertion, we need to update all the balancing information for the nodes on the path back to the root, but the reason that insertion is potentially difficult is that inserting a node could violate the AVL tree property. (For instance, inserting into the AVL tree in Figure 4.29 would destroy the balance condition at the node with key 8.) If this is the case, then the property has to be restored before the insertion step is considered over. It turns out that this can always be done with a simple modification to the tree, known as a rotation. We describe rotations in the following section.

Figure 4.29 Two binary search trees. Only the left tree is AVL.

Figure 4.30 Smallest AVL tree of height 9

4.4.1. Single Rotation

4.4.2. Double Rotation

Single Rotation

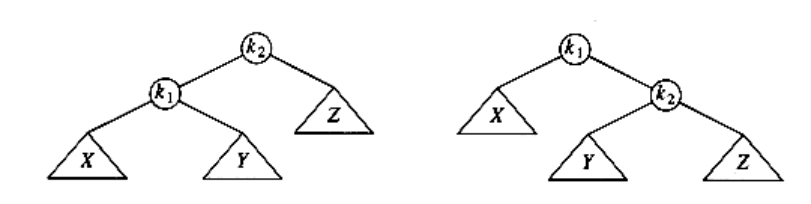

The two trees in Figure 4.31 contain the same elements and are both binary search trees. First of all, in both trees k1 < k2. Second, all elements in the subtree X are smaller than k1 in both trees. Third, all elements in subtree Z are larger than k2. Finally, all elements in subtree Y are in between k1 and k2. The conversion of one of the above trees to the other is known as a rotation. A rotation involves only a few pointer changes (we shall see exactly how many later), and changes the structure of the tree while preserving the search tree property.

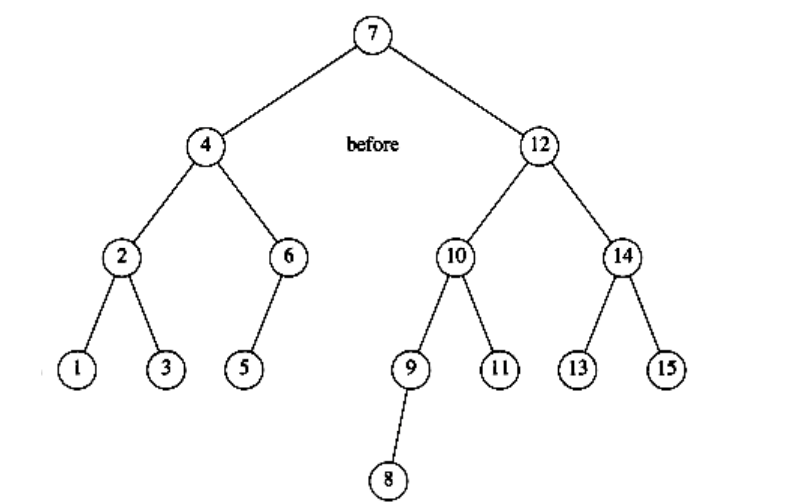

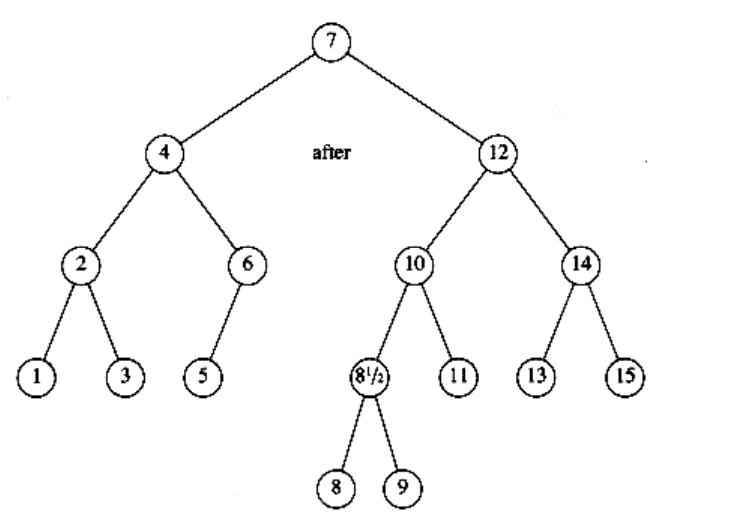

The rotation does not have to be done at the root of a tree; it can be done at any node in the tree, since that node is the root of some subtree. It can transform either tree into the other. This gives a simple method to fix up an AVL tree if an insertion causes some node in an AVL tree to lose the balance property: Do a rotation at that node. The basic algorithm is to start at the node inserted and travel up the tree, updating the balance information at every node on the path. If we get to the root without having found any badly balanced nodes, we are done. Otherwise, we do a rotation at the first bad node found, adjust its balance, and are done (we do not have to continue going to the root). In many cases, this is sufficient to rebalance the tree. For instance, in Figure 4.32, after the insertion of the in the original AVL tree on the left, node 8 becomes unbalanced. Thus, we do a single rotation between 7 and 8, obtaining thetree on the right.

Figure 4.31 Single rotation

Figure 4.32 AVL property destroyed by insertion of , then fixed by a rotation

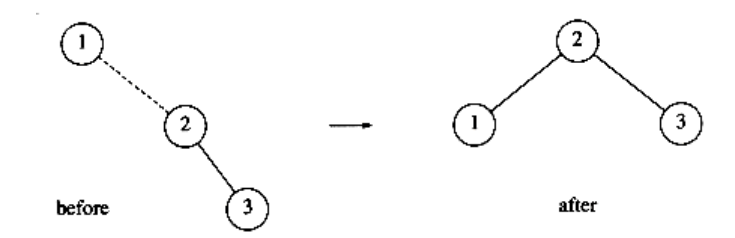

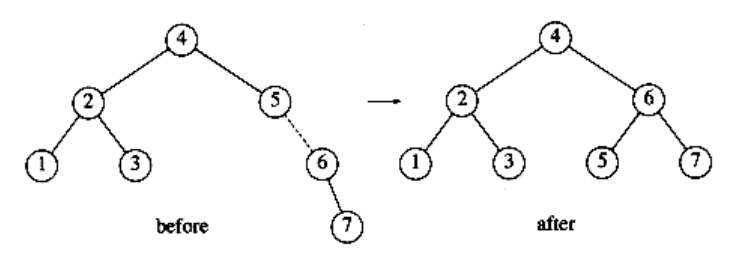

Let us work through a rather long example. Suppose we start with an initially empty AVL tree and insert the keys 1 through 7 in sequential order. The first problem occurs when it is time to insert key 3, because the AVL property is violated at the root. We perform a single rotation between the root and its right child to fix the problem. The tree is shown in the following figure, before and after the rotation:

To make things clearer, a dashed line indicates the two nodes that are the subject of the rotation. Next, we insert the key 4, which causes no problems, but the insertion of 5 creates a violation at node 3, which is fixed by a single rotation. Besides the local change caused by the rotation, the programmer must remember that the rest of the tree must be informed of this change. Here, this means that 2’s right child must be reset to point to 4 instead of 3. This is easy to forget to do and would destroy the tree (4 would be inaccessible).

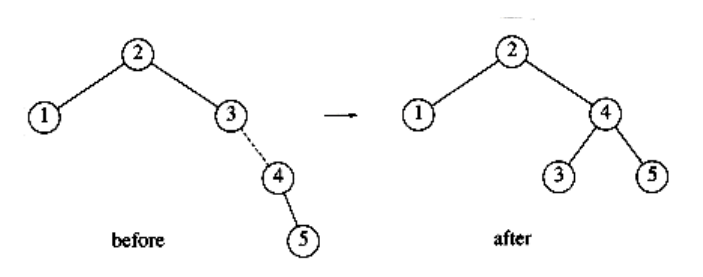

Next, we insert 6. This causes a balance problem for the root, since its left subtree is of height 0, and its right subtree would be height 2. Therefore, we perform a single rotation at the root between 2 and 4.

The rotation is performed by making 2 a child of 4 and making 4’s original left subtree the new right subtree of 2. Every key in this subtree must lie between 2 and 4, so this transformation makes sense. The next key we insert is 7, which causes another rotation.

Double Rotation

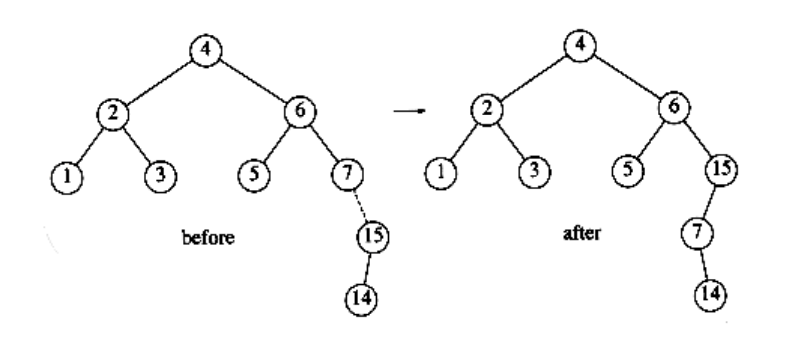

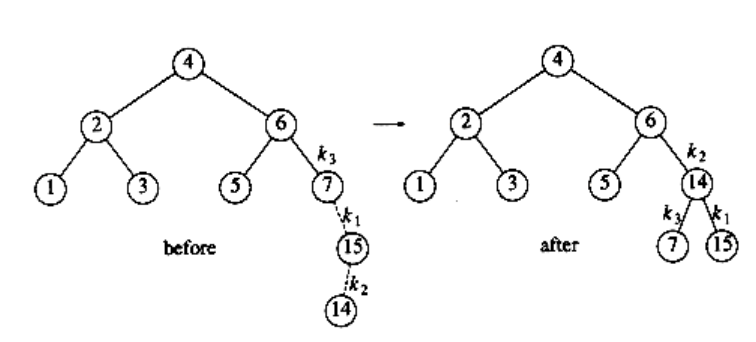

The algorithm described in the preceding paragraphs has one problem. There is a case where the rotation does not fix the tree. Continuing our example, suppose we insert keys 8 through 15 in reverse order. Inserting 15 is easy, since it does not destroy the balance property, but inserting 14 causes a height imbalance at node 7.

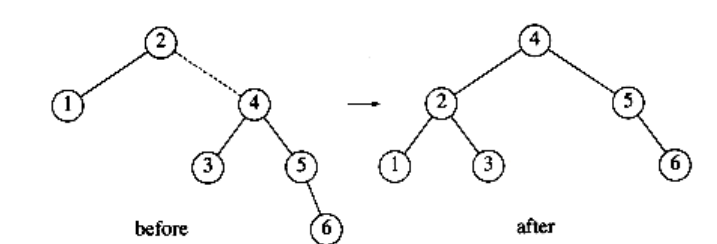

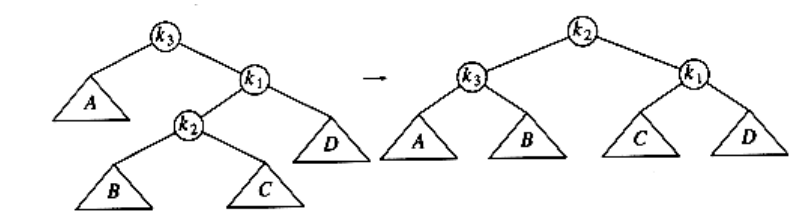

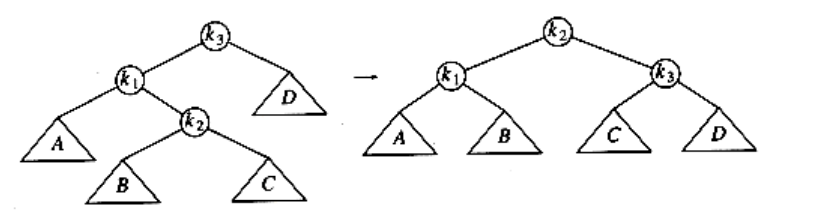

As the diagram shows, the single rotation has not fixed the height imbalance. The problem is that the height imbalance was caused by a node inserted into the tree containing the middle elements (tree Y in Fig. 4.31) at the same time as the other trees had identical heights. The case is easy to check for, and the solution is called a double rotation, which is similar to a single rotation but involves four subtrees instead of three. In Figure 4.33, the tree on the left is converted to the tree on the right. By the way, the effect is the same as rotating between k1 and k2 and then between k2 and k3. There is a symmetric case, which is also shown (see Fig. 4.34).

Figure 4.33 (Right-left) double rotation

Figure 4.34 (Left-right) double rotation

In our example, the double rotation is a right-left double rotation and involves 7, 15, and 14. Here, k3 is the node with key 7, k1 is the node with key 15, and k2 is the node with key 14. Subtrees A, B, C, and D are all empty.

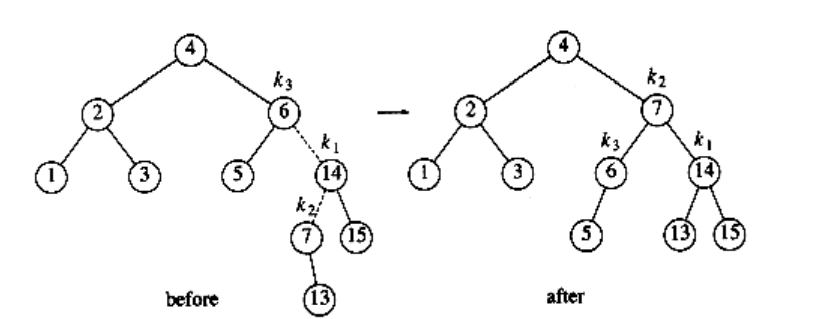

Next we insert 13, which requires a double rotation. Here the double rotation is again a right-left double rotation that will involve 6, 14, and 7 and will restore the tree. In this case, k3 is the node with key 6, k1 is the node with key 14, and k2 is the node with key 7. Subtree A is the tree rooted at the node with key 5, subtree B is the empty subtree that was originally the left child of the node with key 7, subtree C is the tree rooted at the node with key 13, and finally, subtree D is the tree rooted at the node with key 15.

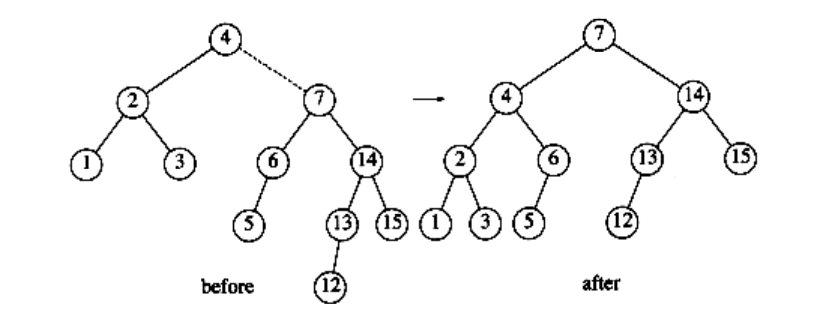

If 12 is now inserted, there is an imbalance at the root. Since 12 is not between 4 and 7, we know that the single rotation will work.

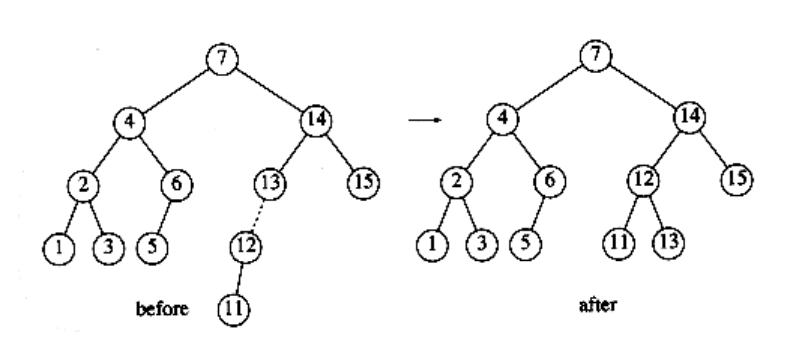

Insertion of 11 will require a single rotation:

To insert 10, a single rotation needs to be performed, and the same is true for the subsequent insertion of 9. We insert 8 without a rotation, creating the almost perfectly balanced tree that follows.

Finally, we insert to show the symmetric case of the double rotation.

Notice that causes the node containing 9 to become unbalanced. Since is between 9 and 8 (which is 9’s child on the path to , a double rotation needs to be performed, yielding the following tree.

The reader can verify that any imbalance caused by an insertion into an AVL tree can always be fixed by either a single or double rotation. The programming details are fairly straightforward, except that there are several cases. To insert a new node with key x into an AVL tree T, we recursively insert x into the appropriate subtree of T (let us call this Tlr). If the height of Tlr does not change, then we are done. Otherwise, if a height imbalance appears in T, we do the appropriate single or double rotation depending on x and the keys in T and Tlr, update the heights (making the connection from the rest of the tree above), and are done. Since one rotation always suffices, a carefully coded nonrecursive version generally turns out to be significantly faster than the recursive version. However, nonrecursive versions are quite difficult to code correctly, so many programmers implement AVL trees recursively.

Another efficiency issue concerns storage of the height information. Since all that is really required is the difference in height, which is guaranteed to be small, we could get by with two bits (to represent +1, 0, -1) if we really try. Doing so will avoid repetitive calculation of balance factors but results in some loss of clarity. The resulting code is somewhat more complicated than if the height were stored at each node. If a recursive routine is written, then speed is probably not the main consideration. In this case, the slight speed advantage obtained by storing balance factors hardly seems worth the loss of clarity and relative simplicity. Furthermore, since most machines will align this to at least an 8-bit boundary anyway, there is not likely to be any difference in the amount of space used. Eight bits will allow us to store absolute heights of up to 255. Since the tree is balanced, it is inconceivable that this would be insufficient (see the exercises).

With all this, we are ready to write the AVL routines. We will do only a partial job and leave the rest as an exercise. First, we need the declarations. These are given in Figure 4.35. We also need a quick function to return the height of a node. This function is necessary to handle the annoying case of a NULL pointer. This is shown in Figure 4.36. The basic insertion routine is easy to write, sinceit consists mostly of function calls (see Fig. 4.37).

typedef struct avl_node *avl_ptr;

struct avl_node

{

element_type element;

avl_ptr left;

avl_ptr right;

int height;

};

typedef avl_ptr SEARCH_TREE;

Figure 4.35 Node declaration for AVL trees

int

height(avl_ptr p)

{

if(p == NULL)

return -1;

else

return p->height;

}

Figure 4.36 Function to compute height of an AVL node

For the trees in Figure 4.38, s_rotate_left converts the tree on the left to the tree on the right, returning a pointer to the new root. s_rotate_right is symmetric. The code is shown in Figure 4.39.

The last function we will write will perform the double rotation pictured in Figure 4.40, for which the code is shown in Figure 4.41.

Deletion in AVL trees is somewhat more complicated than insertion. Lazy deletion is probably the best strategy if deletions are relatively infrequent.