The Stack ADT

Stack Model

A stack is a list with the restriction that inserts and deletes can be performed in only one position, namely the end of the list called the top. The fundamental operations on a stack are push, which is equivalent to an insert, and pop, which deletes the most recently inserted element. The most recently inserted element can be examined prior to performing a pop by use of the top routine. A pop or top on an empty stack is generally considered an error in the stack ADT. On the other hand, running out of space when performing a push is an implementation error but not an ADT error.

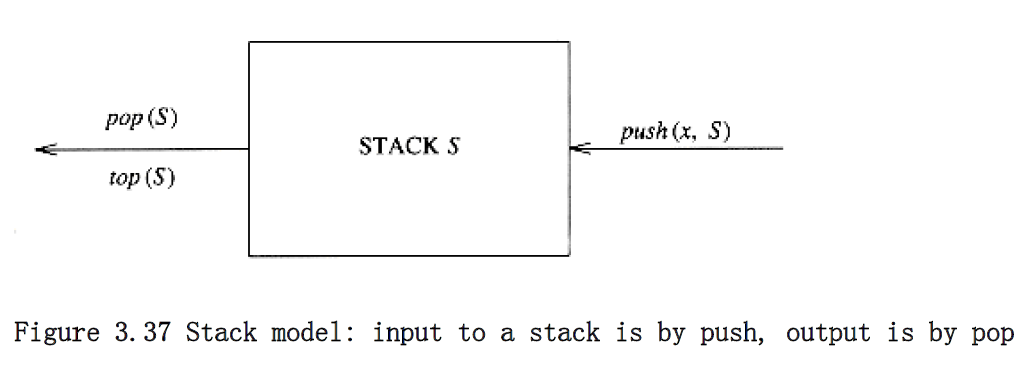

Stacks are sometimes known as LIFO (last in, first out) lists. The model depicted in Figure 3.37 signifies only that pushes are input operations and pops and tops are output. The usual operations to make empty stacks and test for emptiness are part of the repertoire, but essentially all that you can do to a stack is push and pop.

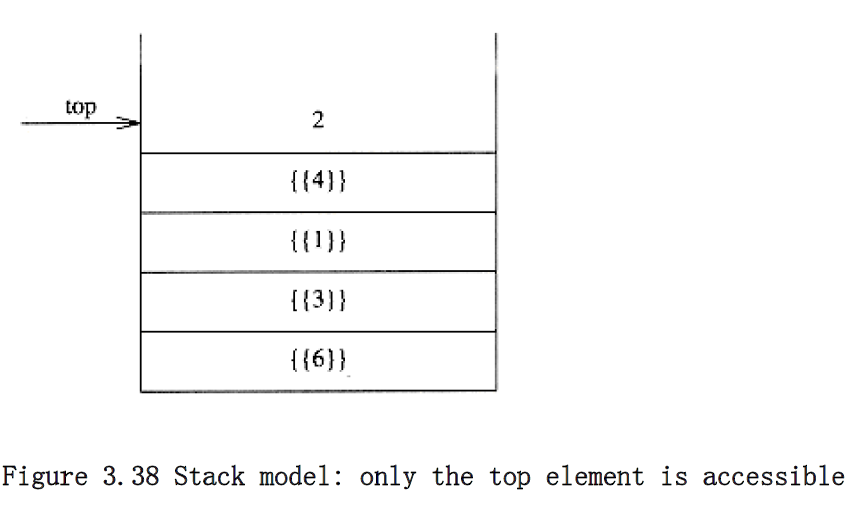

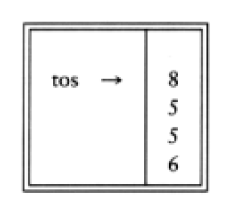

Figure 3.38 shows an abstract stack after several operations. The general model is that there is some element that is at the top of the stack, and it is the only element that is visible.

Implementation of Stacks

Of course, since a stack is a list, any list implementation will do. We will give two popular implementations. One uses pointers and the other uses an array, but, as we saw in the previous section, if we use good programming principles the calling routines do not need to know which method is being used.

Linked List Implementation of Stacks

The first implementation of a stack uses a singly linked list. We perform a push by inserting at the front of the list. We perform a pop by deleting the element at the front of the list. A top operation merely examines the element at the front of the list, returning its value. Sometimes the pop and top operations are combined into one. We could use calls to the linked list routines of the previous section, but we will rewrite the stack routines from scratch for the sake of clarity.

First, we give the definitions in Figure 3.39. We implement the stack using a header. Then Figure 3.40 shows that an empty stack is tested for in the same manner as an empty list.

Creating an empty stack is also simple. We merely create a header node; make_null sets the next pointer to NULL (see Fig. 3.41). The push is implemented as an insertion into the front of a linked list, where the front of the list serves as the top of the stack (see Fig. 3.42). The top is performed by examining the element in the first position of the list (see Fig. 3.43). Finally, we implement pop as a delete from the front of the list (see Fig. 3.44).

It should be clear that all the operations take constant time, because nowhere in any of the routines is there even a reference to the size of the stack (except for emptiness), much less a loop that depends on this size. The drawback of this implementation is that the calls to malloc and free are expensive, especially in comparison to the pointer manipulation routines. Some of this can be avoided by using a second stack, which is initially empty. When a cell is to be disposed from the first stack, it is merely placed on the second stack. Then, when new cells are needed for the first stack, the second stack is checked first.

Array Implementation of Stacks

An alternative implementation avoids pointers and is probably the more popular solution. The only potential hazard with this strategy is that we need to declare an array size ahead of time. Generally this is not a problem, because in typical applications, even if there are quite a few stack operations, the actual number of elements in the stack at any time never gets too large. It is usually easy to declare the array to be large enough without wasting too much space. If this is not possible, then a safe course would be to use a linked list implementation.

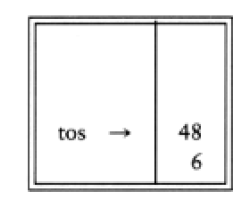

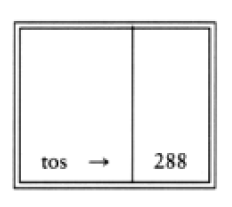

If we use an array implementation, the implementation is trivial. Associated with each stack is the top of stack, tos, which is -1 for an empty stack (this is how an empty stack is initialized). To push some element x onto the stack, we increment tos and then set STACK[tos] = x, where STACK is the array representing the actual stack. To pop, we set the return value to STACK[tos] and then decrement tos. Of course, since there are potentially several stacks, the STACK array and tos are part of one structure representing a stack. It is almost always a bad idea to use global variables and fixed names to represent this (or any) data structure, because in most real-life situations there will be more than one stack. When writing your actual code, you should attempt to follow the model as closely as possible, so that no part of your code, except for the stack routines, can attempt to access the array or top-of-stack variable implied by each stack. This is true for all ADT operations. Modern languages such as Ada and C++ can actually enforce this rule.

typedef struct node *node_ptr;

struct node

{

element_type element;

node_ptr next;

};

typedef node_ptr STACK;

/* Stack implementation will use a header. */

Figure 3.39 Type declaration for linked list implementation of the stack ADT

int

is_empty(STACK S)

{

return(S->next == NULL);

}

Figure 3.40 Routine to test whether a stack is empty-linked list implementation

STACK

create_stack(void)

{

STACK S;

S = (STACK) malloc(sizeof(struct node));

if(S == NULL)

fatal_error("Out of space!!!");

return S;

}

void make_null(STACK S)

{

if(S != NULL)

S->next = NULL;

else

error("Must use create_stack first");

}

Figure 3.41 Routine to create an empty stack-linked list implementation

void push(element_type x, STACK S)

{

node_ptr tmp_cell;

tmp_cell = (node_ptr) malloc(sizeof (struct node));

if(tmp_cell == NULL)

fatal_error("Out of space!!!");

else{

tmp_cell->element = x;

tmp_cell->next = S->next;

S->next = tmp_cell;

}

}

Figure 3.42 Routine to push onto a stack-linked list implementation

element_type

top(STACK S)

{

if(is_empty(S))

error("Empty stack");

else

return S->next->element;

}

Figure 3.43 Routine to return top element in a stack–linked list implementation

void pop(STACK S)

{

node_ptr first_cell;

if(is_empty(S))

error("Empty stack");

else{

first_cell = S->next;

S->next = S->next->next;

free(first_cell);

}

}

Figure 3.44 Routine to pop from a stack–linked list implementation

Notice that these operations are performed in not only constant time, but very fast constant time. On some machines, pushes and pops (of integers) can be written in one machine instruction, operating on a register with auto-increment and auto-decrement addressing. The fact that most modern machines have stack operations as part of the instruction set enforces the idea that the stack is probably the most fundamental data structure in computer science, after the array.

One problem that affects the efficiency of implementing stacks is error testing. Our linked list implementation carefully checked for errors. As described above, a pop on an empty stack or a push on a full stack will overflow the array bounds and cause a crash. This is obviously undesirable, but if checks for these conditions were put in the array implementation, they would likely take as much time as the actual stack manipulation. For this reason, it has become a common practice to skimp on error checking in the stack routines, except where error handling is crucial (as in operating systems). Although you can probably get away with this in most cases by declaring the stack to be large enough not to overflow and ensuring that routines that use pop never attempt to pop an empty stack, this can lead to code that barely works at best, especially when programs get large and are written by more than one person or at more than one time. Because stack operations take such fast constant time, it is rare that a significant part of the running time of a program is spent in these routines. This means that it is generally not justifiable to omit error checks. You should always write the error checks; if they are redundant, you can always comment them out if they really cost too much time. Having said all this, we can now write routines to implement a general stack using arrays.

A STACK is defined in Figure 3.45 as a pointer to a structure. The structure contains the top_of_stack and stack_size fields. Once the maximum size is known, the stack array can be dynamically allocated. Figure 3.46 creates a stack of a given maximum size. Lines 3-5 allocate the stack structure, and lines 6-8 allocate the stack array. Lines 9 and 10 initialize the top_of_stack and stack_size fields. The stack array does not need to be initialized. The stack is returned at line 11.

The routine dispose_stack should be written to free the stack structure. This routine first frees the stack array and then the stack structure (See Figure 3.47). Since create_stack requires an argument in the array implementation, but not in the linked list implementation, the routine that uses a stack will need to know which implementation is being used unless a dummy parameter is added for the later implementation. Unfortunately, efficiency and software idealism often create conflicts.

struct stack_record

{

unsigned int stack_size;

int top_of_stack;

element_type *stack_array;

};

typedef struct stack_record *STACK;

define EMPTY_TOS (-1) /* Signifies an empty stack */

Figure 3.45 STACK definition--array implementaion

STACK

create_stack(unsigned int max_elements)

{

STACK S;

/*1*/ if(max_elements < MIN_STACK_SIZE)

/*2*/ error("Stack size is too small");

/*3*/ S = (STACK) malloc(sizeof(struct stack_record));

/*4*/ if(S == NULL)

/*5*/ fatal_error("Out of space!!!");

/*6*/ S->stack_array = (element_type *)

malloc(sizeof(element_type) * max_elements);

/*7*/ if(S->stack_array == NULL)

/*8*/ fatal_error("Out of space!!!");

/*9*/ S->top_of_stack = EMPTY_TOS;

/*10*/ S->stack_size = max_elements;

/*11*/ return(S);

}

Figure 3.46 Stack creation–array implementaion

void dispose_stack(STACK S)

{

if(S != NULL){

free(S->stack_array);

free(S);

}

}

Figure 3.47 Routine for freeing stack–array implementation

We have assumed that all stacks deal with the same type of element. In many languages, if there are different types of stacks, then we need to rewrite a new version of the stack routines for each different type, giving each version a different name. A cleaner alternative is provided in C++, which allows one to write a set of generic stack routines and essentially pass the type as an argument.* C++ also allows stacks of several different types to retain the same procedure and function names (such as push and pop): The compiler decides which routines are implied by checking the type of the calling routine.

*This is somewhat of an oversimplification.

Having said all this, we will now rewrite the four stack routines. In true ADT spirit, we will make the function and procedure heading look identical to the linked list implementation. The routines themselves are very simple and follow the written description exactly (see Figs. 3.48 to 3.52).

Pop is occasionally written as a function that returns the popped element (and alters the stack). Although current thinking suggests that functions should not change their input variables, Figure 3.53 illustrates that this is the most convenient method in C.

int

is_empty(STACK S)

{

return(S->top_of_stack == EMPTY_TOS);

}

Figure 3.48 Routine to test whether a stack is empty–array implementation

void make_null(STACK S)

{

S->top_of_stack = EMPTY_TOS;

}

Figure 3.49 Routine to create an empty stack–array implementation

void push(element_type x, STACK S)

{

if(is_full(S))

error("Full stack");

else

S->stack_array[ ++S->top_of_stack ] = x;

}

Figure 3.50 Routine to push onto a stack–array implementation

element_type

top(STACK S)

{

if(is_empty(S))

error("Empty stack");

else

return S->stack_array[ S->top_of_stack ];

}

Figure 3.51 Routine to return top of stack–array implementation

void pop(STACK S)

{

if(is_empty(S))

error("Empty stack");

else

S->top_of_stack--;

}

Figure 3.52 Routine to pop from a stack–array implementation

element_type

pop(STACK S)

{

if(is_empty(S))

error("Empty stack");

else

return S->stack_array[ S->top_of_stack-- ];

}

Figure 3.53 Routine to give top element and pop a stack–array implementation

Applications

It should come as no surprise that if we restrict the operations allowed on a list, those operations can be performed very quickly. The big surprise, however, is that the small number of operations left are so powerful and important. We give three of the many applications of stacks. The third application gives a deep insight into how programs are organized.

Balancing Symbols

Compilers check your programs for syntax errors, but frequently a lack of one symbol (such as a missing brace or comment starter) will cause the compiler to spill out a hundred lines of diagnostics without identifying the real error.

A useful tool in this situation is a program that checks whether everything is balanced. Thus, every right brace, bracket, and parenthesis must correspond to their left counterparts. The sequence [()] is legal, but [(] is wrong. Obviously, it is not worthwhile writing a huge program for this, but it turns out that it is easy to check these things. For simplicity, we will just check for > balancing of parentheses, brackets, and braces and ignore any other character that appears.

The simple algorithm uses a stack and is as follows:

Make an empty stack. Read characters until end of file. If the character is an open anything, push it onto the stack. If it is a close anything, then if the stack is empty report an error. Otherwise, pop the stack. If the symbol popped is not the corresponding opening symbol, then report an error. At end of file, if the stack is not empty report an error.

You should be able to convince yourself that this algorithm works. It is clearly linear and actually makes only one pass through the input. It is thus on-line and quite fast. Extra work can be done to attempt to decide what to do when an error is reported–such as identifying the likely cause.

Postfix Expressions

Suppose we have a pocket calculator and would like to compute the cost of a shopping trip. To do so, we add a list of numbers and multiply the result by 1.06; this computes the purchase price of some items with local sales tax added. If the items are 4.99, 5.99, and 6.99, then a natural way to enter this would be the sequence 4.99 + 5.99 + 6.99 * 1.06 = Depending on the calculator, this produces either the intended answer, 19.05, or the scientific answer, 18.39. Most simple four-function calculators will give the first answer, but better calculators know that multiplication has higher precedence than addition.

On the other hand, some items are taxable and some are not, so if only the first and last items were actually taxable, then the sequence 4.99 * 1.06 + 5.99 + 6.99 * 1.06 = would give the correct answer (18.69) on a scientific calculator and the wrong answer (19.37) on a simple calculator. A scientific calculator generally comes with parentheses, so we can always get the right answer by parenthesizing, but with a simple calculator we need to remember intermediate results.

A typical evaluation sequence for this example might be to multiply 4.99 and 1.06, saving this answer as a~1~. We then add 5.99 and a~1~, saving the result in a~1~.

We multiply 6.99 and 1.06, saving the answer in a~2~, and finish by adding a~l~ and a~2~, leaving the final answer in al. We can write this sequence of operations as

follows:

4.99 1.06 * 5.99 + 6.99 1.06 * +

This notation is known as postfix or reverse Polish notation and is evaluated exactly as we have described above. The easiest way to do this is to use a stack.

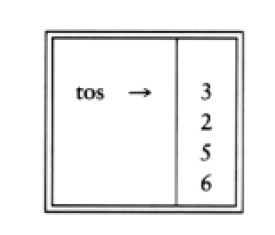

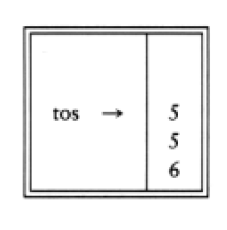

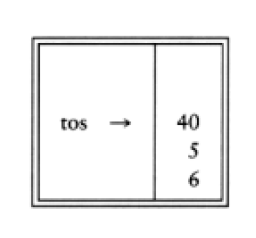

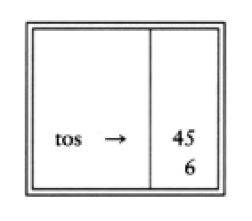

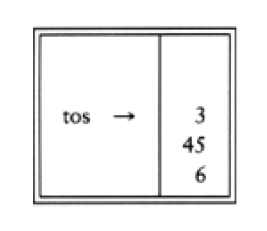

When a number is seen, it is pushed onto the stack; when an operator is seen, the operator is applied to the two numbers (symbols) that are popped from the stack and the result is pushed onto the stack. For instance, the postfix expression

6 5 2 3 + 8 * + 3 + *

is evaluated as follows: The first four symbols are placed on the stack. The resulting stack is

Infix to Postfix Conversion

Not only can a stack be used to evaluate a postfix expression, but we can also use a stack to convert an expression in standard form (otherwise known as infix) into postfix. We will concentrate on a small version of the general problem by allowing only the operators +, *, and

(,), and insisting on the usual precedence rules. We will further assume that the expression is legal. Suppose we want to convert the infix expression

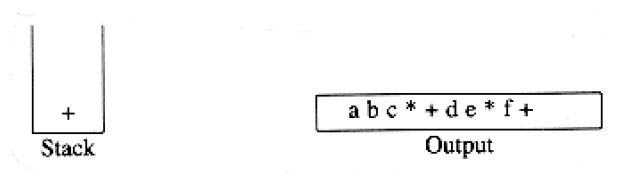

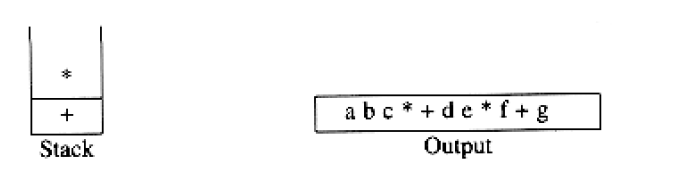

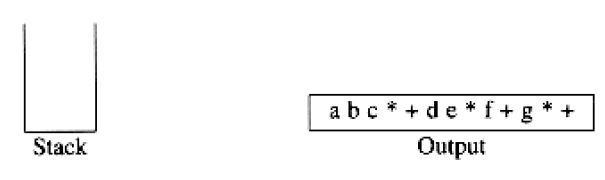

a + b ~~ c + (d ~~ e + f) ~*~ g into postfix. A correct answer is a b c * + d e * f + g * +.

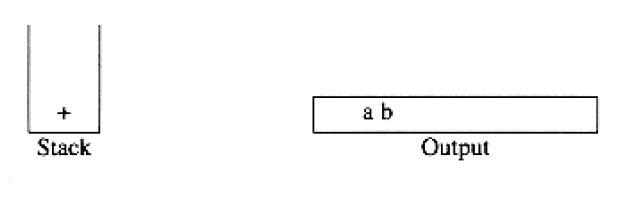

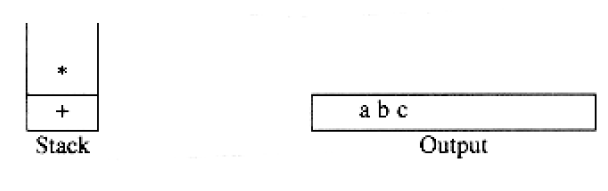

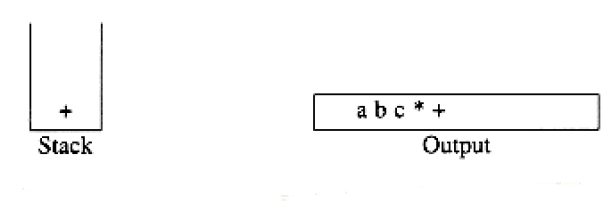

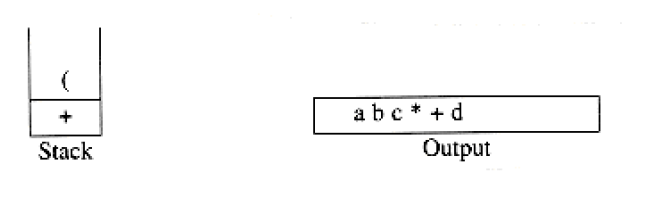

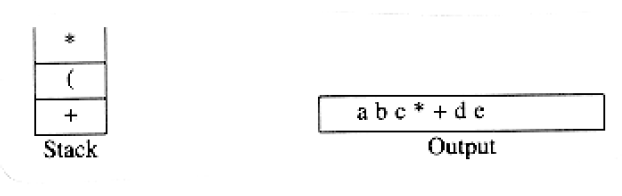

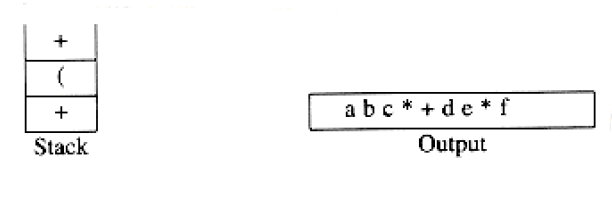

When an operand is read, it is immediately placed onto the output. Operators are not immediately output, so they must be saved somewhere. The correct thing to do is to place operators that have been seen, but not placed on the output, onto the stack. We will also stack left parentheses when they are encountered. We start with an initially empty stack.

If we see a right parenthesis, then we pop the stack, writing symbols until we encounter a (corresponding) left parenthesis, which is popped but not output.

If we see any other symbol (’+’,’*’, ‘(’)), then we pop entries from the stack until we find an entry of lower priority. One exception is that we never remove a ‘(’ from the stack except when processing a ‘)’. For the purposes of this operation, ‘+’ has lowest priority and ‘(’ highest. When the popping is done, we push the operand onto the stack).

Finally, if we read the end of input, we pop the stack until it is empty, writing symbols onto the output.

To see how this algorithm performs, we will convert the infix expression above into its postfix form. First, the symbol a is read, so it is passed through to the output. Then ‘+’ is read and pushed onto the stack. Next b is read and passed through to the output. The state of affairs at this juncture is as follows:

exponentiation associates right to left: 2^23^ = 2^8^ = 256 not 4^3^ = 64. We leave as an exercise the problem of adding exponentiation to the repertoire of assignments.

Function Calls

The algorithm to check balanced symbols suggests a way to implement function calls. The problem here is that when a call is made to a new function, all the variables local to the calling routine need to be saved by the system, since otherwise the new function will overwrite the calling routine’s variables. Furthermore, the current location in the routine must be saved so that the new function knows where to go after it is done. The variables have generally been assigned by the compiler to machine registers, and there are certain to be conflicts (usually all procedures get some variables assigned to register #1), especially if recursion is involved. The reason that this problem is similar to balancing symbols is that a function call and function return are essentially the same as an open parenthesis and closed parenthesis, so the same ideas should work.

When there is a function call, all the important information that needs to be saved, such as register values (corresponding to variable names) and the return address (which can be obtained from the program counter, which is typically in a register), is saved “on a piece of paper” in an abstract way and put at the top of a pile. Then the control is transferred to the new function, which is free to replace the registers with its values. If it makes other function calls, it follows the same procedure. When the function wants to return, it looks at the “paper” at the top of the pile and restores all the registers. It then makes the return jump.

Clearly, all of this work can be done using a stack, and that is exactly what happens in virtually every programming language that implements recursion. The information saved is called either an activation record or stack frame. The stack in a real computer frequently grows from the high end of your memory partition downwards, and on many systems there is no checking for overflow. There is always the possibility that you will run out of stack space by having too many simultaneously active functions. Needless to say, running out of stack space is always a fatal error.

In languages and systems that do not check for stack overflow, your program will crash without an explicit explanation. On these systems, strange things may happen when your stack gets too big, because your stack will run into part of your program. It could be the main program, or it could be part of your data, especially if you have a big array. If it runs into your program, your program will be corrupted; you will have nonsense instructions and will crash as soon as they are executed. If the stack runs into your data, what is likely to happen is that when you write something into your data, it will destroy stack information – probably the return address – and your program will attempt to return to some weird address and crash.

In normal events, you should not run out of stack space; doing so is usually an indication of runaway recursion (forgetting a base case). On the other hand, some perfectly legal and seemingly innocuous program can cause you to run out of stack space. The routine in Figure 3.54, which prints out a linked list, is perfectly legal and actually correct. It properly handles the base case of an empty list, and the recursion is fine. This program can be proven correct. Unfortunately, if the list contains 20,000 elements, there will be a stack of 20,000 activation records representing the nested calls of line 3. Activation records are typically large because of all the information they contain, so this program is likely to run out of stack space. (If 20,000 elements are not enough to make the program crash, replace the number with a larger one.)

This program is an example of an extremely bad use of recursion known as tail recursion. Tail recursion refers to a recursive call at the last line. Tail recursion can be mechanically eliminated by changing the recursive call to a goto preceded by one assignment per function argument. This simulates the recursive call because nothing needs to be saved – after the recursive call finishes, there is really no need to know the saved values. Because of this, we can just go to the top of the function with the values that would have been used in a recursive call. The program in Figure 3.55 shows the improved version. Keep in mind that you should use the more natural while loop construction. The goto is used here to show how a compiler might automatically remove the recursion.

Removal of tail recursion is so simple that some compilers do it automatically. Even so, it is best not to find out that yours does not.

void /* Not using a header */

print_list(LIST L)

{

/*1*/ if(L != NULL){

/*2*/ print_element(L->element);

/*3*/ print_list(L->next);

}

}

Figure 3.54 A bad use of recursion: printing a linked list

void print_list(LIST L) /* No header */{

top:

if(L != NULL){

print_element(L->element);

L = L->next;

goto top;

}

}

Figure 3.55 Printing a list without recursion; a compiler might do this (you should not)

Recursion can always be completely removed (obviously, the compiler does so in converting to assembly language), but doing so can be quite tedious. The general strategy requires using a stack and is obviously worthwhile only if you can manage to put only the bare minimum on the stack. We will not dwell on this further, except to point out that although nonrecursive programs are certainly generally faster than recursive programs, the speed advantage rarely justifies the lack of clarity that results from removing the recursion.