A Brief Introduction to Recursion

Most mathematical functions that we are familiar with are described by a simple formula. For instance, we can convert temperatures from Fahrenheit to Celsius by applying the formula C = 5(F - 32)/9 Given this formula, it is trivial to write a C function; with declarations and braces removed, the one-line formula translates to one line of C.

Mathematical functions are sometimes defined in a less standard form. As an example, we can define a function f, valid on nonnegative integers, that satisfies f(0) = 0 and f(x) = 2f(x - 1) + x2. From this definition we see that f(1) = 1, f(2) = 6, f(3) = 21, and f(4) = 58. A function that is defined in terms of itself is called recursive. C allows functions to be recursive.* It is important to remember that what C provides is merely an attempt to follow the recursive spirit. Not all mathematically recursive functions are efficiently (or correctly) implemented by C’s simulation of recursion. The idea is that the recursive function f ought to be expressible in only a few lines, just like a non-recursive function. Figure 1.2 shows the recursive implementation of f.

*Using recursion for numerical calculations is usually a bad idea. We have done so to illustrate the basic points.

Lines 1 and 2 handle what is known as the base case, that is, the value for which the function is directly known without resorting to recursion. Just as declaring f(x) = 2 f(x - 1) + x2 is meaningless, mathematically, without including the fact that f (0) = 0, the recursive C function doesn’t make sense without a base case. Line 3 makes the recursive call.

There are several important and possibly confusing points about recursion. A common question is: Isn’t this just circular logic? The answer is that although we are defining a function in terms of itself, we are not defining a particular instance of the function in terms of itself. In other words, evaluating f(5) by computing f(5) would be circular. Evaluating f(5) by computing f(4) is not circular–unless, of course f(4) is evaluated by eventually computing f(5). The two most important issues are probably the how and why questions. In Chapter 3, the how and why issues are formally resolved. We will give an incomplete description here.

It turns out that recursive calls are handled no differently from any others. If f is called with the value of 4, then line 3 requires the computation of 2 * f(3) + 4 * 4. Thus, a call is made to compute f(3). This requires the computation of 2 * f(2) + 3 * 3. Therefore, another call is made to compute f(2). This means that 2 * f(1) + 2 * 2 must be evaluated. To do so, f(1) is computed as 2 * f(0) + 1 * 1. Now, f(0) must be evaluated. Since this is a base case, we know a priority that f(0) = 0. This enables the completion of the calculation for f(1), which is now seen to be 1. Then f(2), f(3), and finally f(4) can be determined. All the bookkeeping needed to keep track of pending function calls (those started but waiting for a recursive call to complete), along with their variables, is done by the computer automatically. An important point, however, is that recursive calls will keep on being made until a base case is reached. For instance, an attempt to evaluate f(-1) will result in calls to f(-2), f(-3), and so on. Since this will never get to a base case, the program won’t be able to compute the answer (which is undefined anyway). Occasionally, a much more subtle error is made, which is exhibited in Figure 1.3. The error in the program in Figure 1.3 is that bad(1) is defined, by line 3, to be bad(1). Obviously, this doesn’t give any clue as to what bad(1) actually is. The computer will thus repeatedly make calls to bad(1) in an attempt to resolve its values. Eventually, its bookkeeping system will run out of space, and the program will crash. Generally, we would say that this function doesn’t work for one special case but is correct otherwise. This isn’t true here, since bad(2) calls bad(1). Thus, bad(2) cannot be evaluated either. Furthermore, bad(3), bad(4), and bad(5) all make calls to bad (2). Since bad(2) is unevaluable, none of these values are either. In fact, this program doesn’t work for any value of n, except 0. With recursive programs, there is no such thing as a “special case.”

These considerations lead to the first two fundamental rules of recursion:

-

Base cases. You must always have some base cases, which can be solved without recursion.

-

Making progress. For the cases that are to be solved recursively, the recursive call must always be to a case that makes progress toward a base case.

Throughout this book, we will use recursion to solve problems. As an example of a nonmathematical use, consider a large dictionary. Words in dictionaries are defined in terms of other words. When we look up a word, we might not always understand the definition, so we might have to look up words in the definition. Likewise, we might not understand some of those, so we might have to continue this search for a while. As the dictionary is finite, eventually either we will come to a point where we understand all of the words in some definition (and thus understand that definition and retrace our path through the other definitions), or we will find that the definitions are circular and we are stuck, or that some word we need to understand a definition is not in the dictionary.

int bad(unsigned int n){

/*2*/ return 0;

else

/*3*/ return(bad (n/3 + 1) + n - 1);

}

Figure 1.3 A nonterminating recursive program

Our recursive strategy to understand words is as follows: If we know the meaning of a word, then we are done; otherwise, we look the word up in the dictionary. If we understand all the words in the definition, we are done; otherwise, we figure out what the definition means by recursively looking up the words we don’t know. This procedure will terminate if the dictionary is well defined but can loop indefinitely if a word is either not defined or circularly defined.

Printing Out Numbers

Suppose we have a positive integer, n, that we wish to print out. Our routine will have the heading print_out(n). Assume that the only I/O routines available will take a single-digit number and output it to the terminal. We will call this routine print_digit; for example, print_digit(4) will output a 4 to the terminal.

Recursion provides a very clean solution to this problem. To print out 76234, we need to first print out 7623 and then print out 4. The second step is easily accomplished with the statement print_digit(n%10), but the first doesn’t seem any simpler than the original problem. Indeed it is virtually the same problem, so we can solve it recursively with the statement print_out(n/10).

This tells us how to solve the general problem, but we still need to make sure that the program doesn’t loop indefinitely. Since we haven’t defined a base case yet, it is clear that we still have something to do. Our base case will be print_digit(n) if 0 n < 10. Now print_out(n) is defined for every positive number from 0 to 9, and larger numbers are defined in terms of a smaller positive number. Thus, there is no cycle. The entire procedure* is shown Figure 1.4.

*The term procedure refers to a function that returns void.

We have made no effort to do this efficiently. We could have avoided using the mod routine (which is very expensive) because n%10 = n - n/10 * 10.

Recursion and Induction

Let us prove (somewhat) rigorously that the recursive number-printing program works. To do so, we’ll use a proof by induction.

THEOREM 1.4

The recursive number-printing algorithm is correct for n 0.

PROOF:

First, if n has one digit, then the program is trivially correct, since it merely makes a call to print_digit. Assume then that print_out works for all numbers of k or fewer digits. A number of k + 1 digits is expressed by its first k digits followed by its least significant digit. But the number formed by the first k digits is exactly n/10 , which, by the indicated hypothesis is correctly printed, and the last digit is n mod10, so the program prints out any (k + 1)-digit number correctly. Thus, by induction, all numbers are correctly printed.

void print_out(unsigned int n) /* print nonnegative n */{

if(n<10) print_digit(n);

else{

print_out(n/10);

print_digit(n%10);

}

}

Figure 1.4 Recursive routine to print an integer

This proof probably seems a little strange in that it is virtually identical to the algorithm description. It illustrates that in designing a recursive program, all smaller instances of the same problem (which are on the path to a base case) may be assumed to work correctly. The recursive program needs only to combine solutions to smaller problems, which are “magically” obtained by recursion, into a solution for the current problem. The mathematical justification for this is proof by induction. This gives the third rule of recursion:

- Design rule. Assume that all the recursive calls work.

This rule is important because it means that when designing recursive programs, you generally don’t need to know the details of the bookkeeping arrangements, and you don’t have to try to trace through the myriad of recursive calls. Frequently, it is extremely difficult to track down the actual sequence of recursive calls. Of course, in many cases this is an indication of a good use of recursion, since the computer is being allowed to work out the complicated details.

The main problem with recursion is the hidden bookkeeping costs. Although these costs are almost always justifiable, because recursive programs not only simplify the algorithm design but also tend to give cleaner code, recursion should never be used as a substitute for a simple for loop. We’ll discuss the overhead involved in recursion in more detail in Section 3.3.

When writing recursive routines, it is crucial to keep in mind the four basic rules of recursion:

-

Base cases. You must always have some base cases, which can be solved without recursion.

-

Making progress. For the cases that are to be solved recursively, the recursive call must always be to a case that makes progress toward a base case.

-

Design rule. Assume that all the recursive calls work.

-

Compound interest rule. Never duplicate work by solving the same instance of a problem in separate recursive calls.

The fourth rule, which will be justified (along with its nickname) in later sections, is the reason that it is generally a bad idea to use recursion to evaluate simple mathematical functions, such as the Fibonacci numbers. As long as you keep these rules in mind, recursive programming should be straightforward.

Summary

This chapter sets the stage for the rest of the book. The time taken by an algorithm confronted with large amounts of input will be an important criterion for deciding if it is a good algorithm. (Of course, correctness is most important.) Speed is relative. What is fast for one problem on one machine might be slow for another problem or a different machine. We will begin to address these issues in the next chapter and will use the mathematics discussed here to establish a formal model.

Exercises

1.1 Write a program to solve the selection problem. Let k = n/2. Draw a table showing the running

time of your program for various values of n.

1.2 Write a program to solve the word puzzle problem.

1.3 Write a procedure to output an arbitrary real number (which might be negative) using only

print_digit for I/O.

1.4 C allows statements of the form #include filename

which reads filename and inserts its contents in place of the include statement. Include statements may be nested; in other words, the file filename may itself contain an include statement, but, obviously, a file can’t include itself in any chain. Write a program that reads in a file and outputs the file as modified by the include statements.

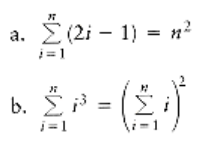

1.5 Prove the following formulas:

a. log x < x for all x > 0

b. log(ab) = b log a

1.6 Evaluate the following sums:

1.7 Estimate

*1.8 What is 2100 (mod 5)?

1.9 Let Fi be the Fibonacci numbers as defined in Section 1.2. Prove the following:

**c. Give a precise closed-form expression for Fn.

1.10 Prove the following formulas:

References

There are many good textbooks covering the mathematics reviewed in this chapter. A small subset is [1], [2], [3], [11], [13], and [14]. Reference [11] is specifically geared toward the analysis

of algorithms. It is the first volume of a three-volume series that will be cited throughout this text. More advanced material is covered in [6].

Throughout this book we will assume a knowledge of C [10]. Occasionally, we add a feature where necessary for clarity. We also assume familiarity with pointers and recursion (the recursion summary in this chapter is meant to be a quick review). We will attempt to provide hints on their use where appropriate throughout the textbook. Readers not familiar with these should consult [4], [8], [12], or any good intermediate programming textbook.

General programming style is discussed in several books. Some of the classics are [5], [7], and [9].

-

M. O. Albertson and J. P. Hutchinson, Discrete Mathematics with Algorithms, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1988.

-

Z. Bavel, Math Companion for Computer Science, Reston Publishing Company, Reston, Va., 1982.

-

R. A. Brualdi, Introductory Combinatorics, North-Holland, New York, 1977.

-

W. H. Burge, Recursive Programming Techniques, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass., 1975.

-

E. W. Dijkstra, A Discipline of Programming, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1976.

-

R. L. Graham, D. E. Knuth, and O. Patashnik, Concrete Mathematics, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass., 1989.

-

D. Gries, The Science of Programming, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1981.

-

P. Helman and R. Veroff, Walls and Mirrors: Intermediate Problem Solving and Data Structures, 2d ed., Benjamin Cummings Publishing, Menlo Park, Calif., 1988.

-

B. W. Kernighan and P. J. Plauger, The Elements of Programming Style, 2d ed., McGraw- Hill, New York, 1978.

-

B. W. Kernighan and D. M. Ritchie, The C Programming Language, 2d ed., Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1988.

-

D. E. Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 1: Fundamental Algorithms, 2d ed., Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass., 1973.

-

E. Roberts, Thinking Recursively, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1986.

-

F. S. Roberts, Applied Combinatorics, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1984.

-

A. Tucker, Applied Combinatorics, 2d ed., John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1984.