Running Time Calculations

There are several ways to estimate the running time of a program. The previous table was obtained empirically. If two programs are expected to take similar times, probably the best way to decide which is faster is to code them both up and run them!

Generally, there are several algorithmic ideas, and we would like to eliminate the bad ones early, so an analysis is usually required. Furthermore, the ability to do an analysis usually provides insight into designing efficient algorithms. The analysis also generally pinpoints the bottlenecks, which are worth coding carefully.

To simplify the analysis, we will adopt the convention that there are no particular units of time. Thus, we throw away leading constants. We will also throw away low-order terms, so what we are essentially doing is computing a Big- Oh running time. Since Big-Oh is an upper bound, we must be careful to never underestimate the running time of the program. In effect, the answer provided is a guarantee that the program will terminate within a certain time period. The program may stop earlier than this, but never later.

A Simple Example

Here is a simple program fragment to calculate

unsigned int sum(int n)

{

unsigned int i, partial_sum;

/*1*/ partial_sum = 0;

/*2*/ for(i=1; i<=n; i++)

/*3*/ partial_sum += i*i*i;

/*4*/ return(partial_sum);

}

The analysis of this program is simple. The declarations count for no time. Lines 1 and 4 count for one unit each. Line 3 counts for three units per time executed (two multiplications and one addition) and is executed n times, for a total of 3n units. Line 2 has the hidden costs of initializing i, testing i n, and incrementing i. The total cost of all these is 1 to initialize, n + 1 for all the tests, and n for all the increments, which is 2n + 2. We ignore the costs of calling the function and returning, for a total of 5n + 4. Thus, we say that this function is O (n).

If we had to perform all this work every time we needed to analyze a program, the task would quickly become infeasible. Fortunately, since we are giving the answer in terms of Big-Oh, there are lots of shortcuts that can be taken without affecting the final answer. For instance, line 3 is obviously an O (1) statement (per execution), so it is silly to count precisely whether it is two, three, or four units – it does not matter. Line 1 is obviously insignificant compared to the for loop, so it is silly to waste time here. This leads to several obvious general rules.

General Rules

RULE 1-FOR LOOPS:

The running time of a for loop is at most the running time of the statements inside the for loop (including tests) times the number of iterations.

RULE 2-NESTED FOR LOOPS:

Analyze these inside out. The total running time of a statement inside a group of nested for loops is the running time of the statement multiplied by the product of the sizes of all the for loops.

As an example, the following program fragment is O(n2):

for(i=0; i<n; i++)

for(j=0; j<n; j++)

k++;

RULE 3-CONSECUTIVE STATEMENTS:

These just add (which means that the maximum is the one that counts – see 1(a) on page 16).

As an example, the following program fragment, which has O(n) work followed by O(n2) work, is also O (n2):

for(i=0; i<n; i++)

a[i] = 0;

for(i=0; i<n; i++)

for(j=0; j<n; j++)

a[i] += a[j] + i + j;

RULE 4-IF/ELSE:

For the fragment

if(cond)

S1

else

S2

the running time of an if/else statement is never more than the running time of the test plus the larger of the running times of S1 and S2.

Clearly, this can be an overestimate in some cases, but it is never an underestimate.

Other rules are obvious, but a basic strategy of analyzing from the inside (or deepest part) out works. If there are function calls, obviously these must be analyzed first. If there are recursive procedures, there are several options. If the recursion is really just a thinly veiled for loop, the analysis is usually trivial. For instance, the following function is really just a simple loop and is obviously O (n):

unsigned int factorial(unsigned int n){

if(n <= 1)

return 1;

else

return(n * factorial(n-1));

}

This example is really a poor use of recursion. When recursion is properly used, it is difficult to convert the recursion into a simple loop structure. In this case, the analysis will involve a recurrence relation that needs to be solved. To see what might happen, consider the following program, which turns out to be a horrible use of recursion:

/* Compute Fibonacci numbers as described Chapter 1 */

unsigned int fib(unsigned int n){

/*1*/ if(n <= 1)

/*2*/ return 1;

else

/*3*/ return(fib(n-1) + fib(n-2));

}

At first glance, this seems like a very clever use of recursion. However, if the program is coded up and run for values of n around 30, it becomes apparent that this program is terribly inefficient. The analysis is fairly simple. Let T(n) be the running time for the function fib(n). If n = 0 or n = 1, then the running time is some constant value, which is the time to do the test at line 1 and return. We can say that T(0) = T(1) = 1, since constants do not matter. The running time for other values of n is then measured relative to the running time of the base case. For n > 2, the time to execute the function is the constant work at line 1 plus the work at line 3. Line 3 consists of an addition and two function calls. Since the function calls are not simple operations, they must be analyzed by themselves. The first function call is fib(n - 1) and hence, by the definition of T, requires T(n - 1) units of time. A similar argument shows that the second function call requires T(n - 2) units of time. The total time required is then T(n - 1) + T(n - 2) + 2, where the 2 accounts for the work at line 1 plus the addition at line 3. Thus, for n 2, we have the following formula for the running time of fib(n):

T(n) = T(n - 1) + T(n - 2) + 2

Since fib(n) = fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2) it is easy to show by induction that T(n) fib(n). In Section 1.2.5, we showed that fib(n) < (5/3) . A similar calculation shows that fib(n) (3/2) , and so the running time of this program grows exponentially. This is about as bad as possible. By keeping a simple array and using a for loop, the running time can be reduced substantially.

This program is slow because there is a huge amount of redundant work being performed, violating the fourth major rule of recursion (the compound interest rule), which was discussed in Section 1.3. Notice that the first call on line 3, fib(n - 1), actually computes fib(n - 2) at some point. This information is thrown away and recomputed by the second call on line 3. The amount of information thrown away compounds recursively and results in the huge running time. This is perhaps the finest example of the maxim “Don’t compute anything more than once” and should not scare you away from using recursion. Throughout this book, we shall see outstanding uses of recursion.

Solutions for the Maximum Subsequence Sum Problem

We will now present four algorithms to solve the maximum subsequence sum problem posed earlier. The first algorithm is depicted in Figure 2.5. The indices in the for loops reflect the fact that, in C, arrays begin at 0, instead of 1. Also, the algorithm computes the actual subsequences (not just the sum); additional code is required to transmit this information to the calling routine.

Convince yourself that this algorithm works (this should not take much). The running time is O(n) and is entirely due to lines 5 and 6, which consist of an O (1) statement buried inside three nested for loops. The loop at line 2 is of size n.

int max_subsequence_sum(int a[],unsigned int n)

{

int this_sum, max_sum, best_i, best_j, i, j, k;

/*1*/ max_sum = 0; best_i = best_j = -1;

/*2*/ for(i=0; i<n; i++)

/*3*/ for(j=i; j<n; j++)

{

/*4*/ this_sum=0;

/*5*/ for(k = i; k<=j; k++)

/*6*/ this_sum += a[k];

/*7*/ if(this_sum > max_sum){ /* update max_sum, best_i, best_j */

/*8*/ max_sum = this_sum;

/*9*/ best_i = i;

/*10*/ best_j = j;

}

}

/*11*/ return(max_sum);

}

Figure 2.5 Algorithm 1

The second loop has size n - i + 1, which could be small, but could also be of size n. We must assume the worst, with the knowledge that this could make the final bound a bit high. The third loop has size j - i + 1, which, again, we must assume is of size n. The total is O(1 n n n) = O(n). Statement 1 takes only O(1) total, and statements 7 to 10 take only O(n) total, since they are easy statements inside only two loops.

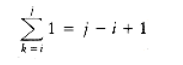

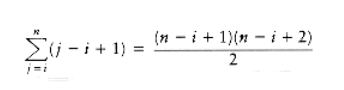

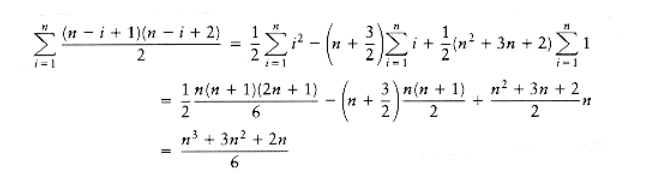

It turns out that a more precise analysis, taking into account the actual size of these loops, shows that the answer is (n), and that our estimate above was a factor of 6 too high (which is all right, because constants do not matter). This is generally true in these kinds of problems. The precise analysis is obtained from the sum 1, which tells how many times line 6 is executed. The sum can be evaluated inside out, using formulas from Section 1.2.3. In particular, we will use the formulas for the sum of the first n integers and first n squares. First we have

There is a recursive and relatively complicated O(n log n) solution to this problem, which we now describe. If there didn’t happen to be an O(n) (linear) solution, this would be an excellent example of the power of recursion. The algorithm uses a “divide-and-conquer” strategy. The idea is to split the problem into two roughly equal subproblems, each of which is half the size of the original. The subproblems are then solved recursively. This is the “divide” part. The “conquer” stage consists of patching together the two solutions of the subproblems, and possibly doing a small amount of additional work, to arrive at a solution for the whole problem.

int max_subsequence_sum(int a[], unsigned int n){

int this_sum, max_sum, best_i, best_j, i, j, k;

/*1*/ max_sum = 0; best_i = best_j = -1;

/*2*/ for(i=0; i<n; i++)

{

/*3*/ this_sum = 0;

/*4*/ for(j=i; j<n; j++)

{

/*5*/ this_sum += a[j];

/*6*/ if(this_sum > max_sum)

/* update max_sum, best_i, best_j */;

}

}

/*7*/ return(max_sum);

}

Figure 2.6 Algorithm 2

In our case, the maximum subsequence sum can be in one of three places. Either it occurs entirely in the left half of the input, or entirely in the right half, or it crosses the middle and is in both halves. The first two cases can be solved recursively. The last case can be obtained by finding the largest sum in the first half that includes the last element in the first half and the largest sum in the second half that includes the first element in the second half. These two sums can then be added together. As an example, consider the following input:

First Half Second Half

----------------------------------------

4 -3 5 -2 -1 2 6 -2

The maximum subsequence sum for the first half is 6 (elements a1 through a3), and for the second half is 8 (elements a6 through a7).

The maximum sum in the first half that includes the last element in the first half is 4 (elements a1 through a4), and the maximum sum in the second half that includes the first element in the second half is 7 (elements a5 though a7). Thus, the maximum sum that spans both halves and goes through the middle is 4 + 7 = 11 (elements a1 through a7).

We see, then, that among the three ways to form a large maximum subsequence, for our example, the best way is to include elements from both halves. Thus, the answer is 11. Figure 2.7 shows an implementation of this strategy.

int max_sub_sequence_sum(int a[], unsigned int n){

return max_sub_sum(a, 0, n-1);

}

int max_sub_sum(int a[], int left, int right)

{

int max_left_sum, max_right_sum;

int max_left_border_sum, max_right_border_sum;

int left_border_sum, right_border_sum;

int center, i;

/*1*/ if (left == right) /* Base Case */

/*2*/ if(a[left] > 0)

/*3*/ return a[left];

else

/*4*/ return 0;

/*5*/ center = (left + right)/2;

/*6*/ max_left_sum = max_sub_sum(a, left, center);

/*7*/ max_right_sum = max_sub_sum(a, center+1, right);

/*8*/ max_left_border_sum = 0; left_border_sum = 0;

/*9*/ for(i=center; i>=left; i--)

{

/*10*/ left_border_sum += a[i];

/*11*/ if(left_border_sum > max_left_border_sum)

/*12*/ max_left_border_sum = left_border_sum;

}

/*13*/ max_right_border_sum = 0; right_border_sum = 0;

/*14*/ for(i=center+1; i<=right; i++)

{

/*15*/ right_border_sum += a[i];

/*16*/ if(right_border_sum > max_right_border_sum)

/*17*/ max_right_border_sum = right_border_sum;

}

/*18*/ return max3(max_left_sum, max_right_sum,

max_left_border_sum+max_right_border_sum);

}

Figure 2.7 Algorithm 3

The code for Algorithm 3 deserves some comment. The general form of the call for the recursive procedure is to pass the input array along with the left and right borders, which delimit the portion of the array that is operated upon. A one-line driver program sets this up by passing the borders 0 and n -1 along with the array.

Lines 1 to 4 handle the base case. If left == right, then there is one element, and this is the maximum subsequence if the element is nonnegative. The case left > right is not possible unless n is negative (although minor perturbations in the code could mess this up). Lines 6 and 7 perform the two recursive calls. We can see that the recursive calls are always on a smaller problem than the original, although, once again, minor perturbations in the code could destroy this property. Lines 8 to 12 and then 13 to 17 calculate the two maximum sums that touch the center divider. The sum of these two values is the maximum sum that spans both halves. The pseudoroutine max3 returns the largest of the three possibilities.

Algorithm 3 clearly requires more effort to code than either of the two previous algorithms. However, shorter code does not always mean better code. As we have seen in the earlier table showing the running times of the algorithms, this algorithm is considerably faster than the other two for all but the smallest of input sizes.

The running time is analyzed in much the same way as for the program that computes the Fibonacci numbers. Let T(n) be the time it takes to solve a maximum subsequence sum problem of size n. If n = 1, then the program takes some constant amount of time to execute lines 1 to 4, which we shall call one unit. Thus, T(1) = 1. Otherwise, the program must perform two recursive calls, the two for loops between lines 9 and 17, and some small amount of bookkeeping, such as lines 5 and 18. The two for loops combine to touch every element from a0 to an_1, and there is constant work inside the loops, so the time expended in lines 9 to 17 is O(n). The code in lines 1 to 5, 8, and 18 is all a constant amount of work and can thus be ignored when compared to O(n). The remainder of the work is performed in lines 6 and 7. These lines solve two subsequence problems of size n/2 (assuming n is even). Thus, these lines take T(n/2) units of time each, for a total of 2T(n/2). The total time for the algorithm then is 2T(n/2) + O(n). This gives the equations

T(1) = 1

T(n) = 2T(n/2) + O(n)

To simplify the calculations, we can replace the O(n) term in the equation above with n; since T(n) will be expressed in Big-Oh notation anyway, this will not affect the answer. In Chapter 7, we shall see how to solve this equation rigorously. For now, if T(n) = 2T(n/2) + n, and T(1) = 1, then T(2) = 4 = 2 * 2, T(4) = 12 = 4 * 3, T(8) = 32 = 8 * 4, T(16) = 80 = 16 * 5. The pattern that is evident, and can be derived, is that if n = 2 , then T(n) = n * (k + 1) = n log n + n = O(n log n).

This analysis assumes n is even, since otherwise n/2 is not defined. By the recursive nature of the analysis, it is really valid only when n is a power of 2, since otherwise we eventually get a subproblem that is not an even size, and the equation is invalid. When n is not a power of 2, a somewhat more complicated analysis is required, but the Big-Oh result remains unchanged.

In future chapters, we will see several clever applications of recursion. Here, we present a fourth algorithm to find the maximum subsequence sum. This algorithm is simpler to implement than the recursive algorithm and also is more efficient. It is shown in Figure 2.8.

int max_subsequence_sum(int a[], unsigned int n)

{

int this_sum, max_sum, best_i, best_j, i, j;

/*1*/ i = this_sum = max_sum = 0; best_i = best_j = -1;

/*2*/ for(j=0; j<n; j++)

{

/*3*/ this_sum += a[j];

/*4*/ if(this_sum > max_sum){ /* update max_sum, best_i, best_j */

/*5*/ max_sum = this_sum;

/*6*/ best_i = i;

/*7*/ best_j = j;

}

else

/*8*/ if(this_sum < 0){

/*9*/ i = j + 1;

/*10*/ this_sum = 0;

}

}

/*11*/ return(max_sum);

}

Figure 2.8 Algorithm 4

It should be clear why the time bound is correct, but it takes a little thought to see why the algorithm actually works. This is left to the reader. An extra advantage of this algorithm is that it makes only one pass through the data, and once a[i] is read and processed, it does not need to be remembered. Thus, if the array is on a disk or tape, it can be read sequentially, and there is no need to store any part of it in main memory. Furthermore, at any point in time, the algorithm can correctly give an answer to the subsequence problem for the data it has already read (the other algorithms do not share this property). Algorithms that can do this are called on-line algorithms. An on-line algorithm that requires only constant space and runs in linear time is just about as good as possible.

Logarithms in the Running Time

The most confusing aspect of analyzing algorithms probably centers around the logarithm. We have already seen that some divide-and-conquer algorithms will run in O(n log n) time. Besides divide-and-conquer algorithms, the most frequent appearance of logarithms centers around the following general rule: An algorithm is O(log n) if it takes constant (O(1)) time to cut the problem size by a fraction (which is usually). On the other hand, if constant time is required to merely reduce the problem by a constant amount (such as to make the problem smaller by 1), then the algorithm is O(n).

Something that should be obvious is that only special kinds of problems can be O (log n). For instance, if the input is a list of n numbers, an algorithm must take (n) merely to read the input in. Thus when we talk about O(log n) algorithms for these kinds of problems, we usually presume that the input is preread. We provide three examples of logarithmic behavior.

Binary Search

The first example is usually referred to as binary search:

BINARY SEARCH:

Given an integer x and integers a1, a2, . . . , an, which are presorted and already in memory, find i such that ai = x, or return i = 0 if x is not in the input.

The obvious solution consists of scanning through the list from left to right and runs in linear time. However, this algorithm does not take advantage of the fact that the list is sorted and is thus not likely to be best. The best strategy is to check if x is the middle element. If so, the answer is at hand. If x is smaller than the middle element, we can apply the same strategy to the sorted subarray to the left of the middle element; likewise, if x is larger than the middle element, we look to the right half. (There is also the case of when to stop.) Figure 2.9 shows the code for binary search (the answer is mid). As usual, the code reflects C’s convention that arrays begin with index 0. Notice that the variables cannot be declared unsigned (why?). In cases where the unsigned qualifier is questionable, we will not use it. As an example, if the unsigned qualifier is dependent on an array not beginning at zero, we will discard it.

We will also avoid using the unsigned type for variables that are counters in a for loop, because it is common to change the direction of a loop counter from increasing to decreasing and the unsigned qualifier is typically appropriate for the former case only. For example, the code in Exercise 2.10 does not work if i is declared unsigned.

Clearly all the work done inside the loop is O(1) per iteration, so the analysis requires determining the number of times around the loop. The loop starts with high - low = n - 1 and finishes with high - low -1. Every time through the loop the value high - low must be at least halved from its previous value; thus,the number of times around the loop is at most log(n - 1) + 2. (As an example, if high - low = 128, then the maximum values of high - low after each iteration are 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0, -1.) Thus, the running time is O(log n). Equivalently, we could write a recursive formula for the running time, but this kind of brute-force approach is usually unnecessary when you understand what is really going on and why.

Binary search can be viewed as our first data structure. It supports the find operation in O(log n) time, but all other operations (in particular insert) require O(n) time. In applications where the data are static (that is, insertions and deletions are not allowed), this could be a very useful data structure. The input would then need to be sorted once, but afterward accesses would be fast. An example could be a program that needs to maintain information about the periodic table of elements (which arises in chemistry and physics). This table is relatively stable, as new elements are added infrequently. The element names could be kept sorted. Since there are only about 110 elements, at most eight accesses would be required to find an element. Performing a sequential search would require many more accesses.

int binary_search(input_type a[ ], input_type x, unsigned int n){

int low, mid, high; /* Can't be unsigned; why? */

/*1*/ low = 0; high = n - 1;

/*2*/ while(low <= high)

{

/*3*/ mid = (low + high)/2;

/*4*/ if(a[mid] < x)

/*5*/ low = mid + 1;

else

/*6*/ if (a[mid] < x)

/*7*/ high = mid - 1;

else

/*8*/ return(mid); /* found */

}

/*9*/ return(NOT_FOUND);

}

Figure 2.9 Binary search.

Euclid’s Algorithm

A second example is Euclid’s algorithm for computing the greatest common divisor. The greatest common divisor (gcd) of two integers is the largest integer that divides both. Thus, gcd (50, 15) = 5. The algorithm in Figure 2.10 computes gcd(m, n), assuming m n. (If n > m, the first iteration of the loop swaps them).

The algorithm works by continually computing remainders until 0 is reached. The last nonzero remainder is the answer. Thus, if m = 1,989 and n = 1,590, then the sequence of remainders is 399, 393, 6, 3, 0. Therefore, gcd (1989, 1590) = 3. As the example shows, this is a fast algorithm.

As before, the entire running time of the algorithm depends on determining how long the sequence of remainders is. Although log n seems like a good answer, it is not at all obvious that the value of the remainder has to decrease by a constant factor, since we see that the remainder went from 399 to only 393 in the example. Indeed, the remainder does not decrease by a constant factor in one iteration. However, we can prove that after two iterations, the remainder is at most half of its original value. This would show that the number of iterations is at most 2 log n = O(log n) and establish the running time. This proof is easy, so we include it here. It follows directly from the following theorem.

unsigned int gcd(unsigned int m, unsigned int n){

unsigned int rem;

/*1*/ while(n > 0){

/*2*/ rem = m % n;

/*3*/ m = n;

/*4*/ n = rem;

}

/*5*/ return(m);

}

Figure 2.10 Euclid’s algorithm.

THEOREM 2.1.

If m > n, then mmod n < m/2.

PROOF:

There are two cases. If n m/2, then obviously, since the remainder is smaller than n, the theorem is true for this case. The other case is n > m/2. But then n goes into m once with a remainder m - n < m/2, proving the theorem.

One might wonder if this is the best bound possible, since 2 log n is about 20 for our example, and only seven operations were performed. It turns out that the constant can be improved slightly, to roughly 1.44 log n, in the worst case (which is achievable if m and n are consecutive Fibonacci numbers). The average- case performance of Euclid’s algorithm requires pages and pages of highly sophisticated mathematical analysis, and it turns out that the average number of iterations is about.

Exponentiation

Our last example in this section deals with raising an integer to a power (which is also an integer). Numbers that result from exponentiation are generally quite large, so an analysis only works if we can assume that we have a machine that can store such large integers (or a compiler that can simulate this). We will count the number of multiplications as the measurement of running time.

int pow(int x, unsigned int n)

{

/*1*/ if(n == 0)/*2*/ return 1;

/*1*/ if(n == 1)/*4*/ return x;

/*5*/ if(even(n))/*6*/ return(pow(x*x, n/2));

else/*7*/ return(pow(x*x, n/2) * x);

}

Figure 2.11 Efficient exponentiation

The obvious algorithm to compute xn uses n - 1 multiples. The recursive algorithm in Figure 2.11 does better. Lines 1 to 4 handle the base case of the recursion. Otherwise, if n is even, we have xn = xn/2 . xn/2, and if n is odd, x = x(n-1)/2 For instance, to compute x62, the algorithm does the following calculations, which involves only nine multiplications:

x3 = (x2)x, x7 = (x3)2x, x15 = (x7)2x, x31 = (x15)2x, x62 = (x31)2

The number of multiplications required is clearly at most 2 log n, because at most two multiplications (if n is odd) are required to halve the problem. Again, a recurrence formula can be written and solved. Simple intuition obviates the need for a brute-force approach.

It is sometimes interesting to see how much the code can be tweaked without affecting correctness. In Figure 2.11, lines 3 to 4 are actually unnecessary, because if n is 1, then line 7 does the right thing. Line 7 can also be rewritten as

/*7*/ return(pow(x, n-1) * x);

without affecting the correctness of the program. Indeed, the program will still run in O(log n), because the sequence of multiplications is the same as before. However, all of the following alternatives for line 6 are bad, even though they look correct:

/*6a*/ return(pow(pow(x, 2), n/2));

/*6b*/ return(pow(pow(x, n/2), 2));

/*6c*/ return(pow(x, n/2) * pow(x, n/2));

Both lines 6a and 6b are incorrect because when n is 2, one of the recursive calls to pow has 2 as the second argument. Thus, no progress is made, and an infinite loop results (in an eventual crash).

Using line 6c affects the efficiency, because there are now two recursive calls of size n/2 instead of only one. An analysis will show that the running time is no longer O(log n). We leave it as an exercise to the reader to determine the new running time.

Checking Your Analysis

Once an analysis has been performed, it is desirable to see if the answer is correct and as good as possible. One way to do this is to code up the program and see if the empirically observed running time matches the running time predicted by the analysis. When n doubles, the running time goes up by a factor of 2 for linear programs, 4 for quadratic programs, and 8 for cubic programs. Programs that run in logarithmic time take only an additive constant longer when n doubles, and programs that run in O(n log n) take slightly more than twice as long to run under the same circumstances. These increases can be hard to spot if the lower-order terms have relatively large coefficients and n is not large enough. An example is the jump from n = 10 to n = 100 in the running time for the various implementations of the maximum subsequence sum problem. It also can be very difficult to differentiate linear programs from O(n log n) programs purely on empirical evidence.

Another commonly used trick to verify that some program is O(f(n)) is to compute the values T(n)/ f(n) for a range of n (usually spaced out by factors of 2), where T(n) is the empirically observed running time. If f(n) is a tight answer for the running time, then the computed values converge to a positive constant. If f(n) is an over-estimate, the values converge to zero. If f (n) is an under-estimate and hence wrong, the values diverge.

As an example, the program fragment in Figure 2.12 computes the probability that two distinct positive integers, less than or equal to n and chosen randomly, are relatively prime. (As n gets large, the answer approaches 6/ 2.)

You should be able to do the analysis for this program instantaneously. Figure 2.13 shows the actual observed running time for this routine on a real computer. The table shows that the last column is most likely, and thus the analysis that you should have gotten is probably correct.Notice that there is not a great deal of difference between O(n2) and O(n2 log n), since logarithms grow so slowly.

A Grain of Salt

Sometimes the analysis is shown empirically to be an over-estimate. If this is the case, then either the analysis needs to be tightened (usually by a clever observation), or it may be the case that the average running time is significantly less than the worst-case running time and no improvement in the bound is possible. There are many complicated algorithms for which the worst- case bound is achievable by some bad input but is usually an over-estimate in practice. Unfortunately, for most of these problems, an average-case analysis is extremely complex (in many cases still unsolved), and a worst-case bound, even though overly pessimistic, is the best analytical result known.

rel = 0; tot = 0;

for(i=1; i<=n; i++)

for(j=i+1; j<=n; j++){

tot++;

if(gcd(i, j) = 1)rel++;

}

printf("Percentage of relatively prime pairs is %lf\n",

((double) rel)/tot);

Figure 2.12 Estimate the probability that two random numbers are relatively prime

n CPU time (T) T/n2 T/n3 T/n2log n

---------------------------------------------------------

100 022 .002200 .000022000 .0004777

200 056 .001400 .000007000 .0002642

300 118 .001311 .000004370 .0002299

400 207 .001294 .000003234 .0002159

500 318 .001272 .000002544 .0002047

---------------------------------------------------------

600 466 .001294 .000002157 .0002024

700 644 .001314 .000001877 .0002006

800 846 .001322 .000001652 .0001977

900 1,086 .001341 .000001490 .0001971

1,000 1,362 .001362 .000001362 .0001972

---------------------------------------------------------

1,500 3,240 .001440 .000000960 .0001969

2,000 5,949 .001482 .000000740 .0001947

4,000 25,720 .001608 .000000402 .0001938

Figure 2.13 Empirical running times for previous routine