Wireless and Mobile Networks

In the telephony world, the past 25 years have been the golden years of cellular telephony. The number of worldwide mobile cellular subscribers increased from 34 million in 1993 to 8.3 billion subscribers in 2019. There are now a larger number of mobile phone subscriptions than there are people on our planet. The many advan- tages of cell phones are evident to all—anywhere, anytime, untethered access to the global telephone network via a highly portable lightweight device. More recently, smartphones, tablets, and laptops have become wirelessly connected to the Internet via a cellular or WiFi network. And increasingly, devices such as gaming consoles, thermostats, home security systems, home appliances, watches, eye glasses, cars, traffic control systems and more are being wirelessly connected to the Internet.

From a networking standpoint, the challenges posed by networking these wire- less and mobile devices, particularly at the link layer and the network layer, are so different from traditional wired computer networks that an individual chapter devoted to the study of wireless and mobile networks (i.e., this chapter) is appropriate.

We’ll begin this chapter with a discussion of mobile users, wireless links, and networks, and their relationship to the larger (typically wired) networks to which they connect. We’ll draw a distinction between the challenges posed by the wireless nature of the communication links in such networks, and by the mobility that these wireless links enable. Making this important distinction—between wireless and mobility—will allow us to better isolate, identify, and master the key concepts in each area.

We will begin with an overview of wireless access infrastructure and associ- ated terminology. We’ll then consider the characteristics of this wireless link in

Section 7.2. We include a brief introduction to code division multiple access (CDMA), a shared-medium access protocol that is often used in wireless networks, in Section 7.2. In Section 7.3, we’ll examine the link-level aspects of the IEEE 802.11 (WiFi) wireless LAN standard in some depth; we’ll also say a few words about Bluetooth wireless personal area networks. In Section 7.4, we’ll provide an overview of cellular Internet access, including 4G and emerging 5G cellular technologies that provide both voice and high-speed Internet access. In Section 7.5, we’ll turn our attention to mobility, focusing on the problems of locating a mobile user, routing to the mobile user, and “handing over” the mobile user who dynamically moves from one point of attachment to the network to another. We’ll examine how these mobility services are implemented in the 4G/5G cellular networks, and the in the Mobile IP standard in Section 7.6. Finally, we’ll consider the impact of wireless links and mobility on transport-layer protocols and networked applications in Section 7.7.

Introduction

Figure 7.1 shows the setting in which we’ll consider the topics of wireless data com- munication and mobility. We’ll begin by keeping our discussion general enough to cover a wide range of networks, including both wireless LANs such as WiFi and 4G and 5G cellular networks; we’ll drill down into a more detailed discussion of specific wireless architectures in later sections. We can identify the following elements in a wireless network:

• Wireless hosts. As in the case of wired networks, hosts are the end-system devices that run applications. A wireless host might be a smartphone, tablet, or laptop, or it could be an Internet of Things (IoT) device such as a sensor, appliance, auto- mobile, or any other of the myriad devices being connected to the Internet. The hosts themselves may or may not be mobile.

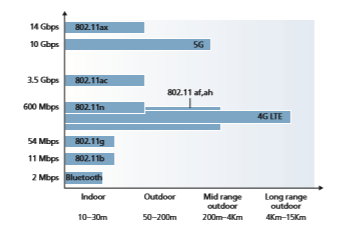

• Wireless links. A host connects to a base station (defined below) or to another wireless host through a wireless communication link. Different wireless link technologies have different transmission rates and can transmit over different distances. Figure 7.2 shows two key characteristics, link transmission rates and coverage ranges, of the more popular wireless network standards. (The figure is only meant to provide a rough idea of these characteristics. For example, some of these types of networks are only now being deployed, and some link rates can increase or decrease beyond the values shown depending on distance, chan- nel conditions, and the number of users in the wireless network.) We’ll cover these standards later in the first half of this chapter; we’ll also consider other wireless link characteristics (such as their bit error rates and the causes of bit errors) in Section 7.2.

In Figure 7.1, wireless links connect wireless hosts located at the edge of the network into the larger network infrastructure. We hasten to add that wireless links are also sometimes used within a network to connect routers, switches, and other network equipment. However, our focus in this chapter will be on the use of wireless communication at the network edge, as it is here that many of the most exciting technical challenges, and most of the growth, are occurring.

• Base station. The base station is a key part of the wireless network infrastructure. Unlike the wireless host and wireless link, a base station has no obvious counter- part in a wired network. A base station is responsible for sending and receiving data (e.g., packets) to and from a wireless host that is associated with that base station. A base station will often be responsible for coordinating the transmission of multiple wireless hosts with which it is associated. When we say a wireless host is “associated” with a base station, we mean that (1) the host is within the wireless communication distance of the base station, and (2) the host uses that base station to relay data between it (the host) and the larger network. Cell towers in cellular networks and access points in 802.11 wireless LANs are examples of base stations.

Figure 7.1, the base station is connected to the larger network (e.g., the Internet, corporate or home network), thus functioning as a link-layer relay between the wireless host and the rest of the world with which the host communicates.

Hosts associated with a base station are often referred to as operating in infrastructure mode, since all traditional network services (e.g., address assign- ment and routing) are provided by the network to which a host is connected via the base station. In ad hoc networks, wireless hosts have no such infrastructure with which to connect. In the absence of such infrastructure, the hosts themselves must provide for services such as routing, address assignment, DNS-like name translation, and more.

When a mobile host moves beyond the range of one base station and into the range of another, it will change its point of attachment into the larger network (i.e., change the base station with which it is associated)—a process referred to as handoff or handover. Such mobility raises many challenging questions. If a host can move, how does one find the mobile host’s current location in the network so that data can be forwarded to that mobile host? How is addressing performed, given that a host can be in one of many possible locations? If the host moves during a TCP connection or phone call, how is data routed so that the connection

continues uninterrupted? These and many (many!) other questions make wireless and mobile networking an area of exciting networking research.

• Network infrastructure. This is the larger network with which a wireless host may wish to communicate.

Having discussed the “pieces” of a wireless network, we note that these pieces can be combined in many different ways to form different types of wireless net- works. You may find a taxonomy of these types of wireless networks useful as you read on in this chapter, or read/learn more about wireless networks beyond this book. At the highest level we can classify wireless networks according to two criteria: (i) whether a packet in the wireless network crosses exactly one wireless hop or multiple wireless hops, and (ii) whether there is infrastructure such as a base station in the network:

• Single-hop, infrastructure-based. These networks have a base station that is con- nected to a larger wired network (e.g., the Internet). Furthermore, all communica- tion is between this base station and a wireless host over a single wireless hop. The 802.11 networks you use in the classroom, café, or library; and the 4G LTE data networks that we will learn about shortly all fall in this category. The vast majority of our daily interactions are with single-hop, infrastructure-based wireless networks.

• Single-hop, infrastructure-less. In these networks, there is no base station that is connected to a wireless network. However, as we will see, one of the nodes in this single-hop network may coordinate the transmissions of the other nodes. Bluetooth networks (that connect small wireless devices such as keyboards, speakers, and headsets, and which we will study in Section 7.3.6) are single-hop, infrastructure-less networks.

• Multi-hop, infrastructure-based. In these networks, a base station is present that is wired to the larger network. However, some wireless nodes may have to relay their communication through other wireless nodes in order to communicate via the base station. Some wireless sensor networks and so-called wireless mesh networks deployed in homes fall in this category.

• Multi-hop, infrastructure-less. There is no base station in these networks, and nodes may have to relay messages among several other nodes in order to reach a destination. Nodes may also be mobile, with connectivity changing among nodes—a class of networks known as mobile ad hoc networks (MANETs). If the mobile nodes are vehicles, the network is a vehicular ad hoc network (VANET). As you might imagine, the development of protocols for such net- works is challenging and is the subject of much ongoing research.

In this chapter, we’ll mostly confine ourselves to single-hop networks, and then mostly to infrastructure-based networks.Let’s now dig deeper into the technical challenges that arise in wireless and mobile networks. We’ll begin by first considering the individual wireless link, defer- ring our discussion of mobility until later in this chapter.

Homework Problems and Questions

Chapter 7 Review Questions SECTION 7.1 R1. What does it mean for a wireless network to be operating in “infrastructure

mode”? If the network is not in infrastructure mode, what mode of operation is it in, and what is the difference between that mode of operation and infra- structure mode?

R2. Both MANET and VANET are multi-hop infrastructure-less wireless net- works. What is the difference between them?

SECTION 7.2 R3. What are the differences between the following types of wireless channel

impairments: path loss, multipath propagation, interference from other sources?

R4. As a mobile node gets farther and farther away from a base station, what are two actions that a base station could take to ensure that the loss probability of a transmitted frame does not increase?

SECTION 7.3 R5. Describe the role of the beacon frames in 802.11.

R6. An access point periodically sends beacon frames. What are the contents of the beacon frames?

R7. Why are acknowledgments used in 802.11 but not in wired Ethernet?

R8. What is the difference between passive scanning and active scanning?

R9. What are the two main purposes of a CTS frame?

R10. Suppose the IEEE 802.11 RTS and CTS frames were as long as the standard DATA and ACK frames. Would there be any advantage to using the CTS and RTS frames? Why or why not?

R11. Section 7.3.4 discusses 802.11 mobility, in which a wireless station moves from one BSS to another within the same subnet. When the APs are intercon- nected with a switch, an AP may need to send a frame with a spoofed MAC address to get the switch to forward the frame properly. Why?R12. What is the difference between Bluetooth and Zigbee in terms of data rate? R13. What is the role of the base station in 4G/5G cellular architecture? With

which other 4G/5G network elements (mobile device, MME, HSS, Serving Gateway Router, PDN Gateway Router) does it directly communicate with in the control plane? In the data plane?

R14. What is an International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI)? R15. What is the role of the Home Subscriber Service (HSS) in 4G/5G cellular

architecture? With which other 4G/5G network elements (mobile device, base station, MME, Serving Gateway Router, PDN Gateway Router) does it directly communicate with in the control plane? In the data plane?

R16. What is the role of the Mobility Management Entity (MME) in 4G/5G cellular architecture? With which other 4G/5G network elements (mobile device, base station, HSS, Serving Gateway Router, PDN Gateway Router) does it directly communicate with in the control plane? In the data plane?

R17. Describe the purpose of two tunnels in the data plane of the 4G/5G cellular architecture. When a mobile device is attached to its own home network, at which 4G/5G network element (mobile device, base station, HSS, MME, Serving Gateway Router, PDN Gateway Router) does each end of each of the two tunnels terminate?

R18. What are the three sublayers in the link layer in the LTE protocol stack? Briefly describe their functions.

R19. Does the LTE wireless access network use FDMA, TDMA, or both? Explain your answer.

R20. Describe the two possible sleep modes of a 4G/5G mobile device. In each of these sleep modes, will the mobile device remain associated with the same base station between the time it goes to sleep and the time it wakes up and first sends/receives a new datagram?

R21. What is meant by a “visited network” and a “home network” in 4G/5G cel- lular architecture?

R22. List three important differences between 4G and 5G cellular networks.

SECTION 7.5 R23. What does it mean that a mobile device is said to be “roaming?” R24. What is meant by “hand over” of a network device? R25. What is the difference between direct and indirect routing of datagrams to/

from a roaming mobile host? R26. What does “triangle routing” mean?

*The terms used above may differ from the terms found in the official Bluetooth Specification. The terms used in the official specifica- tion DO NOT align with Pearson’s commitment to promoting diversity, equality, and inclusion, and protecting against bias and stereo- typing in the global population of the learners we serve. PROBLEMS

SECTION 7.6 R27. Describe the similarity and differences in tunnel configuration when a mobile device

is resident in its home network, versus when it is roaming in a visited network.

R 28. When a mobile device is handed over from one base station to another in a 4G/5G network, which network element makes the decision to initiate that handover? Which network element chooses the target base station to which the mobile device will be handed over?

R 29. Describe how and when the forwarding path of datagrams entering the visited net- work and destined to the mobile device changes before, during, and after hand over.

R 30. Consider the following elements of the Mobile IP architecture: the home net- work, foreign network permanent IP address, home agent, foreign agent, data plane forwarding, Access Point (AP), and WLANs at the network edge. What are the closest equivalent elements in the 4G/5G cellular network architecture?

SECTION 7.7 R31. What are three approaches that can be used to avoid having a single wireless

link degrade the performance of an end-to-end transport-layer TCP connection?

Problems

P1. Consider the single-sender CDMA example in Figure 7.5. What would be the sender’s output (for the 2 data bits shown) if the sender’s CDMA code were (1, 1, -1, 1, 1, -1, -1, 1)?

P2. Consider sender 2 in Figure 7.6. What is the sender’s output to the channel (before it is added to the signal from sender 1), Z2 i,m?

P3. After selecting the AP with which to associate, a wireless host sends an association request frame to the AP, and the AP responds with an association response frame. Once associated with an AP, the host will want to join the subnet (in the IP addressing sense of Section 4.4.2) to which the AP belongs. What does the host do next?

P4. If two CDMA senders have codes (1, 1, 1, -1, 1, -1, -1, -1) and (1, -1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1), would the corresponding receivers be able to decode the data correctly? Justify.

P5. Suppose there are two ISPs providing WiFi access in a particular café, with each ISP operating its own AP and having its own IP address block.

a. Further suppose that by accident, each ISP has configured its AP to oper- ate over channel 11. Will the 802.11 protocol completely break down in this situation? Discuss what happens when two stations, each associated with a different ISP, attempt to transmit at the same time.

b. Now suppose that one AP operates over channel 1 and the other over channel 11. How do your answers change?P6. In step 4 of the CSMA/CA protocol, a station that successfully transmits a frame begins the CSMA/CA protocol for a second frame at step 2, rather than at step 1. What rationale might the designers of CSMA/CA have had in mind by having such a station not transmit the second frame immediately (if the channel is sensed idle)?

P7. Suppose an 802.11b station is configured to always reserve the channel with the RTS/CTS sequence. Suppose this station suddenly wants to transmit 1,000 bytes of data, and all other stations are idle at this time. Assume a transmission rate of 10 Mbps. Calculate the time required to transmit the frame and receive the acknowledgment as a function of SIFS and DIFS, ignoring propagation delay and assuming no bit errors.

P8. Consider the scenario shown in Figure 7.31, in which there are four wireless nodes, A, B, C, and D. The radio coverage of the four nodes is shown via the shaded ovals; all nodes share the same frequency. When A transmits, it can only be heard/received by B; when B transmits, both A and C can hear/ receive from B; when C transmits, both B and D can hear/receive from C; when D transmits, only C can hear/receive from D.

Suppose now that each node has an infinite supply of messages that it wants to send to each of the other nodes. If a message’s destination is not an immediate neighbor, then the message must be relayed. For example, if A wants to send to D, a message from A must first be sent to B, which then sends the mes- sage to C, which then sends the message to D. Time is slotted, with a message transmission time taking exactly one time slot, e.g., as in slotted Aloha. During a slot, a node can do one of the following: (i) send a message, (ii) receive a mes- sage (if exactly one message is being sent to it), (iii) remain silent. As always, if a node hears two or more simultaneous transmissions, a collision occurs and none of the transmitted messages are received successfully. You can assume here that there are no bit-level errors, and thus if exactly one message is sent, it will be received correctly by those within the transmission radius of the sender.

a. Suppose now that an omniscient controller (i.e., a controller that knows the state of every node in the network) can command each node to do whatever it (the omniscient controller) wishes, that is, to send a message, to receive a Figure 7.31 ♦ Scenario for problem P8

message, or to remain silent. Given this omniscient controller, what is the maximum rate at which a data message can be transferred from C to A, given that there are no other messages between any other source/destination pairs?

b. Suppose now that A sends messages to B, and D sends messages to C. What is the combined maximum rate at which data messages can flow from A to B and from D to C?

c. Suppose now that A sends messages to B, and C sends messages to D. What is the combined maximum rate at which data messages can flow from A to B and from C to D?

d. Suppose now that the wireless links are replaced by wired links. Repeat questions (a) through (c) again in this wired scenario.

e. Now suppose we are again in the wireless scenario, and that for every data message sent from source to destination, the destination will send an ACK message back to the source (e.g., as in TCP). Also suppose that each ACK message takes up one slot. Repeat questions (a)–(c) above for this scenario.

P9. Power is a precious resource in mobile devices, and thus the 802.11 standard provides power-management capabilities that allow 802.11 nodes to minimize the amount of time that their sense, transmit, and receive functions and other circuitry need to be “on.” In 802.11, a node is able to explicitly alternate between sleep and wake states. Explain in brief how a node communicates with the AP to perform power management.

P10. Consider the following idealized LTE scenario. The downstream channel (see Figure 7.22) is slotted in time, across F frequencies. There are four nodes, A, B, C, and D, reachable from the base station at rates of 10 Mbps, 5 Mbps, 2.5 Mbps, and 1 Mbps, respectively, on the downstream channel. These rates assume that the base station utilizes all time slots available on all F frequen- cies to send to just one station. The base station has an infinite amount of data to send to each of the nodes, and can send to any one of these four nodes using any of the F frequencies during any time slot in the downstream sub-frame.

a. What is the maximum rate at which the base station can send to the nodes, assuming it can send to any node it chooses during each time slot? Is your solution fair? Explain and define what you mean by “fair.”

b. If there is a fairness requirement that each node must receive an equal amount of data during each one second interval, what is the average transmission rate by the base station (to all nodes) during the downstream sub-frame? Explain how you arrived at your answer.

c. Suppose that the fairness criterion is that any node can receive at most twice as much data as any other node during the sub-frame. What is the average transmission rate by the base station (to all nodes) during the sub- frame? Explain how you arrived at your answer.

P11. In Section 7.5, one proposed solution that allowed mobile users to maintain their IP addresses as they moved among foreign networks was to have a foreign network advertise a highly specific route to the mobile user and use the existingrouting infrastructure to propagate this information throughout the network. We identified scalability as one concern. Suppose that when a mobile user moves from one network to another, the new foreign network advertises a specific route to the mobile user, and the old foreign network withdraws its route. Consider how routing information propagates in a distance-vector algorithm (particularly for the case of interdomain routing among networks that span the globe).

a. Will other routers be able to route datagrams immediately to the new for- eign network as soon as the foreign network begins advertising its route?

b. Is it possible for different routers to believe that different foreign networks contain the mobile user?

c. Discuss the timescale over which other routers in the network will eventu- ally learn the path to the mobile users.

P12. In 4G/5G networks, what effect will handoff have on end-to-end delays of datagrams between the source and destination?

P13. Consider a mobile device that powers on and attaches to an LTE visited network A, and assume that indirect routing to the mobile device from its home network H is being used. Subsequently, while roaming, the device moves out of range of visited network A and moves into range of an LTE visited network B. You will design a handover process from a base sta- tion BS.A in visited network A to a base station BS.B in visited network B. Sketch the series of steps that would need to be taken, taking care to identify the network elements involved (and the networks to which they belong), to accomplish this handover. Assume that following handover, the tunnel from the home network to the visited network will terminate in visiting network B.

P14. Consider again the scenario in Problem P13. But now assume that the tunnel from home network H to visited network A will continue to be used. That is, visited network A will serve as an anchor point following handover. (Aside: this is actually the process used for routing circuit-switched voice calls to a roaming mobile phone in 2G GSM networks.) In this case, additional tunnel(s) will need to be built to reach the mobile device in its resident visited network B. Once again, sketch the series of steps that would need to be taken, taking care to identify the network elements involved (and the networks to which they belong), to accomplish this handover. What are one advantage and one disadvantage of this approach over the approach taken in your solution to Problem P13?

Wireshark Lab: WiFi

At the Web site for this textbook, www.pearsonglobaleditions.com, also mirrored on the instructors’ website, http://gaia.cs.umass.edu/kurose_ross, you’ll find a Wireshark lab for this chapter that captures and studies the 802.11 frames exchanged between a wireless laptop and an access point.Please describe a few of the most exciting projects you have worked on during your career. What were the biggest challenges? In the mid-90s at USC and ISI, I had the great fortune to work with the likes of Steve Deering, Mark Handley, and Van Jacobson on the design of multicast routing protocols (in particular, PIM). I tried to carry many of the architectural design lessons from multicast into the design of ecological monitoring arrays, where for the first time I really began to take applications and multidisciplinary research seriously. The need for jointly innovating in the social and technological space is what interests me so much about my latest area of research, mobile health. The challenges in multicast routing, environmental sensing and

AN INTERVIEW WITH…

Deborah Estrin

Deborah Estrin is a Professor of Computer Science and Associate Dean for Impact at Cornell Tech in New York City and a Professor of Public Health at Weill Cornell Medical College. She received her Ph.D. (1985) in Computer Science from M.I.T. and her B.S. (1980) from UC Berkeley. Estrin’s early research focused on the design of network protocols, including multicast and inter-domain routing. In 2002 Estrin founded the NSF-funded Science and Technology Center at UCLA, Center for Embedded Networked Sensing (CENS http://cens.ucla.edu.). CENS launched new areas of multi-disciplinary computer systems research from sensor networks for environmental monitoring, to participatory sensing and mobile health. As described in her 2013 TEDMED talk, she explores how individuals can benefit from the pervasive data byproducts of digi- tal and IoT interactions for health and life management. Professor Estrin is an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (2007), the National Academy of Engineering (2009), and the National Academy of Medicine (2019). She is a Fellow of the IEEE, ACM, and AAAS. She was selected as the first ACM-W Athena Lecturer (2006), awarded the Anita Borg Institute’s Women of Vision Award for Innovation (2007), inducted into the WITI hall of fame (2008), received honorary doctorates from EPFL (2008) and Uppsala University (2011), and was selected as a MacArthur Fellow (2018).mobile health are as diverse as the problem domains, but what they have in common is the need to keep our eyes open to whether we have the problem definition right as we iterate between design and deployment, prototype and pilot. None of these are problems that could be solved solely analytically, or with simulation or even in constructed laboratory experi- ments. They challenged our ability to retain clean architectures in the presence of messy problems and contexts, and they required extensive collaboration.

What changes and innovations do you see happening in wireless networks and mobility in the future? In a prior edition of this interview I said that I have never put much faith into predicting the future, but I did go on to speculate that we might see the end of feature phones (i.e., those that are not programmable and are used only for voice and text messaging) as smart phones become more and more powerful and the primary point of Internet access for many—and now not so many years later that is clearly the case. I also predicted that we would see the continued proliferation of embedded SIMs by which all sorts of devices have the ability to communicate via the cellular network at low data rates. While that has occurred, we see many devices and “Internet of Things” that use embedded WiFi and other lower power, shorter range, forms of connectivity to local hubs. I did not anticipate at that time the emer- gence of a large consumer wearables market or interactive voice agents like Siri and Alexa. By the time the next edition is published I expect broad proliferation of personal applica- tions that leverage data from IoT and other digital traces.

Where do you see the future of networking and the Internet? Again I think it’s useful to look both back and forward. Previously I commented that the efforts in named data and software-defined networking would emerge to create a more manageable, evolvable, and richer infrastructure and more generally represent moving the role of architecture higher up in the stack. In the beginnings of the Internet, architecture was layer 4 and below, with applications being more siloed/monolithic, sitting on top. Now data and analytics dominate transport. The adoption of SDN (which I was really happy to see introduced into the 7th edition of this book) has been well beyond what I ever anticipated. That said, new challenges have emerged from higher up in the stack. Machine Learning based systems and services favor scale, particularly when they rely on continuous consumer engagement (clicks) for financial viability. The resulting information ecosystem has become far more monolithic than in earlier decades. This is a challenge for networking, the Internet, and frankly our society.What people inspired you professionally? There are three people who come to mind. First, Dave Clark, the secret sauce and under- sung hero of the Internet community. I was lucky to be around in the early days to see him act as the “organizing principle” of the IAB and Internet governance; the priest of rough consensus and running code. Second, Scott Shenker, for his intellectual brilliance, integrity, and persistence. I strive for, but rarely attain, his clarity in defining problems and solutions. He is always the first person I e-mail for advice on matters large and small. Third, my sister Judy Estrin, who had the creativity and commitment to spend the first half of her career bringing ideas and concepts to market; and now has the courage to study, write, and advise on how to rebuild it to support a healthier democracy.

What are your recommendations for students who want careers in computer science and networking? First, build a strong foundation in your academic work, balanced with any and every real- world work experience you can get. As you look for a working environment, seek opportu- nities in problem areas you really care about and with smart teams that you can learn from and work with to build things that matter.This page is intentionally left blank