The Network Layer: Control Plane

In this chapter, we’ll complete our journey through the network layer by covering the control-plane component of the network layer—the network-wide logic that con- trols not only how a datagram is routed along an end-to-end path from the source host to the destination host, but also how network-layer components and services are configured and managed. In Section 5.2, we’ll cover traditional routing algorithms for computing least cost paths in a graph; these algorithms are the basis for two widely deployed Internet routing protocols: OSPF and BGP, that we’ll cover in Sec- tions 5.3 and 5.4, respectively. As we’ll see, OSPF is a routing protocol that operates within a single ISP’s network. BGP is a routing protocol that serves to interconnect all of the networks in the Internet; BGP is thus often referred to as the “glue” that holds the Internet together. Traditionally, control-plane routing protocols have been implemented together with data-plane forwarding functions, monolithically, within a router. As we learned in the introduction to Chapter 4, software-defined networking (SDN) makes a clear separation between the data and control planes, implementing control-plane functions in a separate “controller” service that is distinct, and remote, from the forwarding components of the routers it controls. We’ll cover SDN control- lers in Section 5.5.

In Sections 5.6 and 5.7, we’ll cover some of the nuts and bolts of managing an IP network: ICMP (the Internet Control Message Protocol) and SNMP (the Simple Network Management Protocol).

Introduction

Let’s quickly set the context for our study of the network control plane by recall- ing Figures 4.2 and 4.3. There, we saw that the forwarding table (in the case of destination-based forwarding) and the flow table (in the case of generalized forward- ing) were the principal elements that linked the network layer’s data and control planes. We learned that these tables specify the local data-plane forwarding behavior of a router. We saw that in the case of generalized forwarding, the actions taken could include not only forwarding a packet to a router’s output port, but also drop- ping a packet, replicating a packet, and/or rewriting layer 2, 3 or 4 packet-header fields.

In this chapter, we’ll study how those forwarding and flow tables are computed, maintained and installed. In our introduction to the network layer in Section 4.1, we learned that there are two possible approaches for doing so.

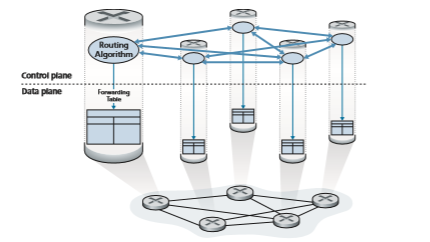

• Per-router control. Figure 5.1 illustrates the case where a routing algorithm runs in each and every router; both a forwarding and a routing function are contained

within each router. Each router has a routing component that communicates with the routing components in other routers to compute the values for its forwarding table. This per-router control approach has been used in the Internet for decades. The OSPF and BGP protocols that we’ll study in Sections 5.3 and 5.4 are based on this per-router approach to control.

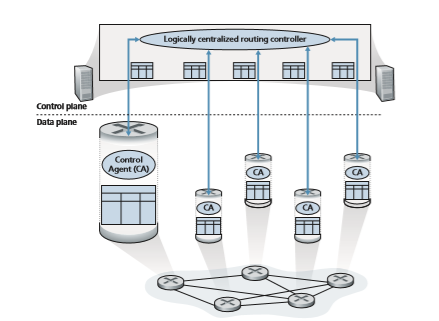

• Logically centralized control. Figure 5.2 illustrates the case in which a logically centralized controller computes and distributes the forwarding tables to be used by each and every router. As we saw in Sections 4.4 and 4.5, the generalized match-plus-action abstraction allows the router to perform traditional IP forward- ing as well as a rich set of other functions (load sharing, firewalling, and NAT) that had been previously implemented in separate middleboxes.

The controller interacts with a control agent (CA) in each of the routers via a well-defined protocol to configure and manage that router’s flow table. Typically, the CA has minimum functionality; its job is to communicate with the controller, and to do as the controller commands. Unlike the routing algorithms in Figure 5.1, the CAs do not directly interact with each other nor do they actively take part in computing the forwarding table. This is a key distinction between per-router control and logically centralized control.

By “logically centralized” control [Levin 2012] we mean that the routing control service is accessed as if it were a single central service point, even though the service is likely to be implemented via multiple servers for fault-tolerance, and performance scalability reasons. As we will see in Section 5.5, SDN adopts this notion of a logically centralized controller—an approach that is finding increased use in production deployments. Google uses SDN to control the rout- ers in its internal B4 global wide-area network that interconnects its data centers [Jain 2013]. SWAN [Hong 2013], from Microsoft Research, uses a logically centralized controller to manage routing and forwarding between a wide area network and a data center network. Major ISP deployments, including COM- CAST’s ActiveCore and Deutsche Telecom’s Access 4.0 are actively integrating SDN into their networks. And as we’ll see in Chapter 8, SDN control is central to 4G/5G cellular networking as well. [AT&T 2019] notes, “ … SDN, isn’t a vision, a goal, or a promise. It’s a reality. By the end of next year, 75% of our network functions will be fully virtualized and software-controlled.” China Telecom and China Unicom are using SDN both within data centers and between data centers [Li 2015].