QUANTIFYING UNCERTAINTY

In which we see how an agent can tame uncertainty with degrees of belief.

ACTING UNDER UNCERTAINTY

Agents may need to handle uncertainty, whether due to partial observability, nondetermin-UNCERTAINTY

ism, or a combination of the two. An agent may never know for certain what state it’s in or where it will end up after a sequence of actions.

We have seen problem-solving agents (Chapter 4) and logical agents (Chapters 7 and 11) designed to handle uncertainty by keeping track of a belief state—a representation of the set of all possible world states that it might be in—and generating a contingency plan that handles every possible eventuality that its sensors may report during execution. Despite its many virtues, however, this approach has significant drawbacks when taken literally as a recipe for creating agent programs:

-

When interpreting partial sensor information, a logical agent must consider every logically possible explanation for the observations, no matter how unlikely. This leads to impossible large and complex belief-state representations.

-

A correct contingent plan that handles every eventuality can grow arbitrarily large and must consider arbitrarily unlikely contingencies.

-

Sometimes there is no plan that is guaranteed to achieve the goal—yet the agent must act. It must have some way to compare the merits of plans that are not guaranteed.

Suppose, for example, that an automated taxi!automated has the goal of delivering a passenger to the airport on time. The agent forms a plan, A90, that involves leaving home 90 minutes before the flight departs and driving at a reasonable speed. Even though the airport is only about 5 miles away, a logical taxi agent will not be able to conclude with certainty that “Plan A90 will get us to the airport in time.” Instead, it reaches the weaker conclusion “Plan A90 will get us to the airport in time, as long as the car doesn’t break down or run out of gas, and I don’t get into an accident, and there are no accidents on the bridge, and the plane doesn’t leave early, and no meteorite hits the car, and . . . .” None of these conditions can be deduced for sure, so the plan’s success cannot be inferred. This is the qualification problem (page 268), for which we so far have seen no real solution.

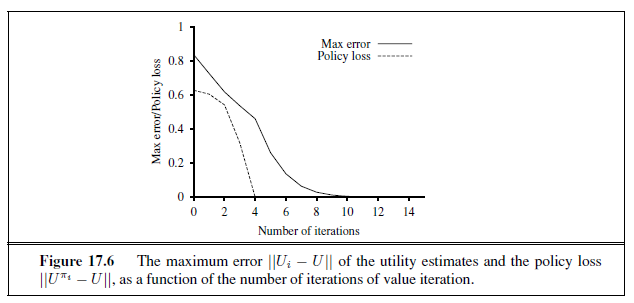

Nonetheless, in some sense A90 is in fact the right thing to do. What do we mean by this? As we discussed in Chapter 2, we mean that out of all the plans that could be executed, A90 is expected to maximize the agent’s performance measure (where the expectation is relative to the agent’s knowledge about the environment). The performance measure includes getting to the airport in time for the flight, avoiding a long, unproductive wait at the airport, and avoiding speeding tickets along the way. The agent’s knowledge cannot guarantee any of these outcomes for A90, but it can provide some degree of belief that they will be achieved. Other plans, such as a~1~80, might increase the agent’s belief that it will get to the airport on time, but also increase the likelihood of a long wait. The right thing to do—the rational decision—therefore depends on both the relative importance of various goals and the likelihood that, and degree to which, they will be achieved. The remainder of this section hones these ideas, in preparation for the development of the general theories of uncertain reasoning and rational decisions that we present in this and subsequent chapters.

Summarizing uncertainty

Let’s consider an example of uncertain reasoning: diagnosing a dental patient’s toothache. Diagnosis—whether for medicine, automobile repair, or whatever—almost always involves uncertainty. Let us try to write rules for dental diagnosis using propositional logic, so that we can see how the logical approach breaks down. Consider the following simple rule:

Toothache ⇒ Cavity .

The problem is that this rule is wrong. Not all patients with toothaches have cavities; some of them have gum disease, an abscess, or one of several other problems:

Toothache ⇒ Cavity ∨GumProblem ∨ Abscess

Unfortunately, in order to make the rule true, we have to add an almost unlimited list of possible problems. We could try turning the rule into a causal rule:

Cavity ⇒ Toothache .

But this rule is not right either; not all cavities cause pain. The only way to fix the rule is to make it logically exhaustive: to augment the left-hand side with all the qualifications required for a cavity to cause a toothache. Trying to use logic to cope with a domain like medical diagnosis thus fails for three main reasons:

-

Laziness: It is too much work to list the complete set of antecedents or consequents needed to ensure an exceptionless rule and too hard to use such rules.

-

Theoretical ignorance: Medical science has no complete theory for the domain.

-

Practical ignorance: Even if we know all the rules, we might be uncertain about a particular patient because not all the necessary tests have been or can be run.

The connection between toothaches and cavities is just not a logical consequence in either direction. This is typical of the medical domain, as well as most other judgmental domains: law, business, design, automobile repair, gardening, dating, and so on. The agent’s knowledge can at best provide only a degree of belief in the relevant sentences. Our main tool for dealing with degrees of belief is probability theory. In the terminology of Section 8.1, the ontological commitments of logic and probability theory are the same—that the world is composed of facts that do or do not hold in any particular case—but the epistemological commitments are different: a logical agent believes each sentence to be true or false or has no opinion, whereas a probabilistic agent may have a numerical degree of belief between 0 (for sentences that are certainly false) and 1 (certainly true).

Probability provides a way of summarizing the uncertainty that comes from our laziness and ignorance, thereby solving the qualification problem. We might not know for sure what afflicts a particular patient, but we believe that there is, say, an 80% chance—that is, a probability of 0.8—that the patient who has a toothache has a cavity. That is, we expect that out of all the situations that are indistinguishable from the current situation as far as our knowledge goes, the patient will have a cavity in 80% of them. This belief could be derived from statistical data—80% of the toothache patients seen so far have had cavities—or from some general dental knowledge, or from a combination of evidence sources.

One confusing point is that at the time of our diagnosis, there is no uncertainty in the actual world: the patient either has a cavity or doesn’t. So what does it mean to say the probability of a cavity is 0.8? Shouldn’t it be either 0 or 1? The answer is that probability statements are made with respect to a knowledge state, not with respect to the real world. We say “The probability that the patient has a cavity, given that she has a toothache, is 0.8.” If we later learn that the patient has a history of gum disease, we can make a different statement: “The probability that the patient has a cavity, given that she has a toothache and a history of gum disease, is 0.4.” If we gather further conclusive evidence against a cavity, we can say “The probability that the patient has a cavity, given all we now know, is almost 0.” Note that these statements do not contradict each other; each is a separate assertion about a different knowledge state.

Uncertainty and rational decisions

Consider again the A90 plan for getting to the airport. Suppose it gives us a 97% chance of catching our flight. Does this mean it is a rational choice? Not necessarily: there might be other plans, such as A180, with higher probabilities. If it is vital not to miss the flight, then it is worth risking the longer wait at the airport. What about A1440, a plan that involves leaving home 24 hours in advance? In most circumstances, this is not a good choice, because although it almost guarantees getting there on time, it involves an intolerable wait—not to mention a possibly unpleasant diet of airport food.

To make such choices, an agent must first have preferences between the different possible outcomes of the various plans. An outcome is a completely specified state, including such factors as whether the agent arrives on time and the length of the wait at the airport. We use utility theory to represent and reason with preferences. (The term utility is used here in the sense of “the quality of being useful,” not in the sense of the electric company or water works.) Utility theory says that every state has a degree of usefulness, or utility, to an agent and that the agent will prefer states with higher utility.

The utility of a state is relative to an agent. For example, the utility of a state in which White has checkmated Black in a game of chess is obviously high for the agent playing White, but low for the agent playing Black. But we can’t go strictly by the scores of 1, 1/2, and 0 that are dictated by the rules of tournament chess—some players (including the authors) might be thrilled with a draw against the world champion, whereas other players (including the former world champion) might not. There is no accounting for taste or preferences: you might think that an agent who prefers jalapeño bubble-gum ice cream to chocolate chocolate chip is odd or even misguided, but you could not say the agent is irrational. A utility function can account for any set of preferences—quirky or typical, noble or perverse. Note that utilities can account for altruism, simply by including the welfare of others as one of the factors.

Preferences, as expressed by utilities, are combined with probabilities in the general theory of rational decisions called decision theory:

Decision theory = probability theory + utility theory .

The fundamental idea of decision theory is that an agent is rational if and only if it chooses the action that yields the highest expected utility, averaged over all the possible outcomes of the action. This is called the principle of maximum expected utility (MEU). Note that “expected” might seem like a vague, hypothetical term, but as it is used here it has a precise meaning: it means the “average,” or “statistical mean” of the outcomes, weighted by the probability of the outcome. We saw this principle in action in Chapter 5 when we touched briefly on optimal decisions in backgammon; it is in fact a completely general principle.

BASIC PROBABILITY NOTATION

For our agent to represent and use probabilistic information, we need a formal language. The language of probability theory has traditionally been informal, written by human mathematicians to other human mathematicians. Appendix A includes a standard introduction to elementary probability theory; here, we take an approach more suited to the needs of AI and more consistent with the concepts of formal logic.

function DT-AGENT(percept ) returns an action

persistent: belief state, probabilistic beliefs about the current state of the world action , the agent’s action

update belief state based on action and percept

calculate outcome probabilities for actions,

given action descriptions and current belief state

select action with highest expected utility

given probabilities of outcomes and utility information

return action

Figure 13.1 A decision-theoretic agent that selects rational actions.

What probabilities are about

Like logical assertions, probabilistic assertions are about possible worlds. Whereas logical assertions say which possible worlds are strictly ruled out (all those in which the assertion is false), probabilistic assertions talk about how probable the various worlds are. In probability theory, the set of all possible worlds is called the sample space. The possible worlds are mutually exclusive and exhaustive—two possible worlds cannot both be the case, and one possible world must be the case. For example, if we are about to roll two (distinguishable) dice, there are 36 possible worlds to consider: (1,1), (1,2), . . ., (6,6). The Greek letter Ω (uppercase omega) is used to refer to the sample space, and ω (lowercase omega) refers to elements of the space, that is, particular possible worlds.

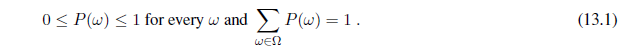

A fully specified probability model associates a numerical probability P (ω) with each possible world.1 The basic axioms of probability theory say that every possible world has a probability between 0 and 1 and that the total probability of the set of possible worlds is 1:

For example, if we assume that each die is fair and the rolls don’t interfere with each other, then each of the possible worlds (1,1), (1,2), . . ., (6,6) has probability 1/36. On the other hand, if the dice conspire to produce the same number, then the worlds (1,1), (2,2), (3,3), etc., might have higher probabilities, leaving the others with lower probabilities.

Probabilistic assertions and queries are not usually about particular possible worlds, but about sets of them. For example, we might be interested in the cases where the two dice add up to 11, the cases where doubles are rolled, and so on. In probability theory, these sets are called events—a term already used extensively in Chapter 12 for a different concept. In AI, the sets are always described by propositions in a formal language. (One such language is described in Section 13.2.2.) For each proposition, the corresponding set contains just those possible worlds in which the proposition holds. The probability associated with a proposition

1 For now, we assume a discrete, countable set of worlds. The proper treatment of the continuous case brings in certain complications that are less relevant for most purposes in AI.

is defined to be the sum of the probabilities of the worlds in which it holds:

For example, when rolling fair dice, we have P (Total =11) = P ((5, 6)) + P ((6, 5)) = 1/36 + 1/36 = 1/18. Note that probability theory does not require complete knowledge of the probabilities of each possible world. For example, if we believe the dice conspire to produce the same number, we might assert that P (doubles) = 1/4 without knowing whether the dice prefer double 6 to double 2. Just as with logical assertions, this assertion constrains the underlying probability model without fully determining it.

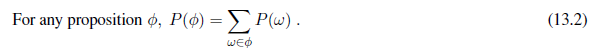

Probabilities such as P (Total = 11) and P (doubles) are called unconditional or priorprobabilities (and sometimes just “priors” for short); they refer to degrees of belief in propositions in the absence of any other information. Most of the time, however, we have some information, usually called evidence, that has already been revealed. For example, the first die may already be showing a 5 and we are waiting with bated breath for the other one to stop spinning. In that case, we are interested not in the unconditional probability of rolling doubles, but the conditional or posterior probability (or just “posterior” for short) of rolling doubles given that the first die is a 5. This probability is written P (doubles |Die1 = 5), where the “ | ” is pronounced “given.” Similarly, if I am going to the dentist for a regular checkup, the probability P (cavity)= 0.2 might be of interest; but if I go to the dentist because I have a toothache, it’s P (cavity | toothache)= 0.6 that matters. Note that the precedence of “ | ” is such that any expression of the form P (. . . | . . .) always means P ((. . .)|(. . .)).

It is important to understand that P (cavity)= 0.2 is still valid after toothache is observed; it just isn’t especially useful. When making decisions, an agent needs to condition on all the evidence it has observed. It is also important to understand the difference between conditioning and logical implication. The assertion that P (cavity | toothache)= 0.6 does not mean “Whenever toothache is true, conclude that cavity is true with probability 0.6” rather it means “Whenever toothache is true and we have no further information, conclude that cavity is true with probability 0.6.” The extra condition is important; for example, if we had the further information that the dentist found no cavities, we definitely would not want to conclude that cavity is true with probability 0.6; instead we need to use P (cavity |toothache ∧ ¬cavity)= 0.

Mathematically speaking, conditional probabilities are defined in terms of unconditional probabilities as follows: for any propositions a and b, we have

The definition makes sense if you remember that observing b rules out all those possible worlds where b is false, leaving a set whose total probability is just P (b). Within that set, the a-worlds satisfy a ∧ b and constitute a fraction P (a ∧ b)/P (b).

The definition of conditional probability, Equation (13.3), can be written in a different form called the product rule:PRODUCT RULE

P (a ∧ b) = P (a | b)P (b) ,

The product rule is perhaps easier to remember: it comes from the fact that, for a and b to be true, we need b to be true, and we also need a to be true given b.

The language of propositions in probability assertions

In this chapter and the next, propositions describing sets of possible worlds are written in a notation that combines elements of propositional logic and constraint satisfaction notation. In the terminology of Section 2.4.7, it is a factored representation, in which a possible world is represented by a set of variable/value pairs.

Variables in probability theory are called random variables and their names begin with an uppercase letter. Thus, in the dice example, Total and Die1 are random variables. Every random variable has a domain—the set of possible values it can take on. The domain of Total for two dice is the set {2, . . . , 12} and the domain of Die1 is {1, . . . , 6}. A Boolean random variable has the domain {true , false} (notice that values are always lowercase); for example, the proposition that doubles are rolled can be written as Doubles = true . By convention, propositions of the form A= true are abbreviated simply as a, while A= false is abbreviated as ¬a. (The uses of doubles , cavity , and toothache in the preceding section are abbreviations of this kind.) As in CSPs, domains can be sets of arbitrary tokens; we might choose the domain of Age to be {juvenile, teen , adult} and the domain of Weather might be {sunny , rain , cloudy , snow}. When no ambiguity is possible, it is common to use a value by itself to stand for the proposition that a particular variable has that value; thus, sunny can stand for Weather = sunny .

The preceding examples all have finite domains. Variables can have infinite domains, too—either discrete (like the integers) or continuous (like the reals). For any variable with an ordered domain, inequalities are also allowed, such as NumberOfAtomsInUniverse ≥ 1070.

Finally, we can combine these sorts of elementary propositions (including the abbreviated forms for Boolean variables) by using the connectives of propositional logic. For example, we can express “The probability that the patient has a cavity, given that she is a teenager with no toothache, is 0.1” as follows:

P(cavity | ¬toothache ∧ teen) = 0.1 .

Sometimes we will want to talk about the probabilities of all the possible values of a random variable. We could write:

P(Weather = sunny) = 0.6

P(Weather = rain) = 0.1

P(Weather = cloudy) = 0.29

P(Weather = snow ) = 0.01 ,

but as an abbreviation we will allow

P(Weather )= 〈0.6, 0.1, 0.29, 0.01〉 ,

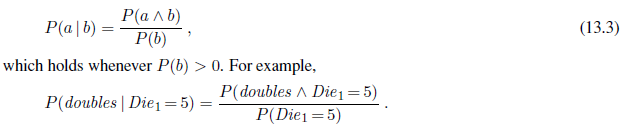

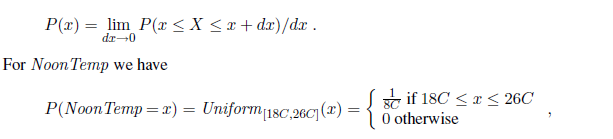

where the bold P indicates that the result is a vector of numbers, and where we assume a predefined ordering 〈sunny , rain , cloudy , snow 〉 on the domain of Weather . We say that the P statement defines a probability distribution for the random variable Weather . The P notation is also used for conditional distributions: P(X |Y ) gives the values of P (X = x~i~ |Y = y~j~) for each possible i, j pair. For continuous variables, it is not possible to write out the entire distribution as a vector, because there are infinitely many values. Instead, we can define the probability that a random variable takes on some value x as a parameterized function of x. For example, the sentence

P (NoonTemp = x) = Uniform~[18C,26C]~(x)

expresses the belief that the temperature at noon is distributed uniformly between 18 and 26 degrees Celsius. We call this a probability density function.

Probability density functions (sometimes called pdfs) differ in meaning from discrete distributions. Saying that the probability density is uniform from 18C to 26C means that there is a 100% chance that the temperature will fall somewhere in that 8C-wide region and a 50% chance that it will fall in any 4C-wide region, and so on. We write the probability density for a continuous random variable X at value x as P (X = x) or just P (x); the intuitive definition of P (x) is the probability that X falls within an arbitrarily small region beginning at x, divided by the width of the region:

where C stands for centigrade (not for a constant). In P (NoonTemp =20.18C)= 1/8C , note that 1/8C is not a probability, it is a probability density. The probability that NoonTemp is exactly 20.18C is zero, because 20.18C is a region of width 0. Some authors use different symbols for discrete distributions and density functions; we use P in both cases, since confusion seldom arises and the equations are usually identical. Note that probabilities are unitless numbers, whereas density functions are measured with a unit, in this case reciprocal degrees.

In addition to distributions on single variables, we need notation for distributions on multiple variables. Commas are used for this. For example, P(Weather ,Cavity) denotes the probabilities of all combinations of the values of Weather and Cavity . This is a 4 × 2 table of probabilities called the joint probability distribution of Weather and Cavity . We can also mix variables with and without values; P(sunny ,Cavity) would be a two-element vector giving the probabilities of a sunny day with a cavity and a sunny day with no cavity. The P notation makes certain expressions much more concise than they might otherwise be. For example, the product rules for all possible values of Weather and Cavity can be written as a single equation:

P(Weather ,Cavity) = P(Weather | Cavity)P(Cavity) ,

instead of as these 4× 2= 8 equations (using abbreviations W and C):

P (W = sunny ∧ C = true) = P (W = sunny|C = true)P (C = true)

P (W = rain ∧ C = true) = P (W = rain |C = true)P (C = true)

P (W = cloudy ∧ C = true) = P (W = cloudy |C = true)P (C = true)

P (W = snow ∧ C = true) = P (W = snow |C = true)P (C = true)

P (W = sunny ∧ C = false) = P (W = sunny|C = false)P (C = false)

P (W = rain ∧ C = false) = P (W = rain |C = false)P (C = false)

P (W = cloudy ∧ C = false) = P (W = cloudy |C = false)P (C = false)

P (W = snow ∧ C = false) = P (W = snow |C = false)P (C = false) .

As a degenerate case, P(sunny , cavity) has no variables and thus is a one-element vector that is the probability of a sunny day with a cavity, which could also be written as P (sunny , cavity) or P (sunny ∧ cavity). We will sometimes use P notation to derive results about individual P values, and when we say “P(sunny)= 0.6” it is really an abbreviation for “P(sunny) is the one-element vector 〈0.6〉, which means that P (sunny)= 0.6.”

Now we have defined a syntax for propositions and probability assertions and we have given part of the semantics: Equation (13.2) defines the probability of a proposition as the sum of the probabilities of worlds in which it holds. To complete the semantics, we need to say what the worlds are and how to determine whether a proposition holds in a world. We borrow this part directly from the semantics of propositional logic, as follows. A possible world is defined to be an assignment of values to all of the random variables under consideration. It is easy to see that this definition satisfies the basic requirement that possible worlds be mutually exclusive and exhaustive (Exercise 13.5). For example, if the random variables are Cavity , Toothache , and Weather , then there are 2× 2× 4= 16 possible worlds. Furthermore, the truth of any given proposition, no matter how complex, can be determined easily in such worlds using the same recursive definition of truth as for formulas in propositional logic.

From the preceding definition of possible worlds, it follows that a probability model is completely determined by the joint distribution for all of the random variables—the so-called full joint probability distribution. For example, if the variables are Cavity , Toothache , and Weather , then the full joint distribution is given by P(Cavity ,Toothache ,Weather ). This joint distribution can be represented as a 2× 2× 4 table with 16 entries. Because every proposition’s probability is a sum over possible worlds, a full joint distribution suffices, in principle, for calculating the probability of any proposition.

Probability axioms and their reasonableness

The basic axioms of probability (Equations (13.1) and (13.2)) imply certain relationships among the degrees of belief that can be accorded to logically related propositions. For example, we can derive the familiar relationship between the probability of a proposition and the probability of its negation:

We can also derive the well-known formula for the probability of a disjunction, sometimes called the inclusion–exclusion principle:

P (a ∨ b) = P (a) + P (b)− P (a ∧ b) . (13.4)

This rule is easily remembered by noting that the cases where a holds, together with the cases where b holds, certainly cover all the cases where a ∨ b holds; but summing the two sets of cases counts their intersection twice, so we need to subtract P (a ∧ b). The proof is left as an exercise (Exercise 13.6).

Equations (13.1) and (13.4) are often called Kolmogorov’s axioms in honor of the Rus-KOLMOGOROV’S AXIOMS

sian mathematician Andrei Kolmogorov, who showed how to build up the rest of probability theory from this simple foundation and how to handle the difficulties caused by continuous variables.2 While Equation (13.2) has a definitional flavor, Equation (13.4) reveals that the axioms really do constrain the degrees of belief an agent can have concerning logically related propositions. This is analogous to the fact that a logical agent cannot simultaneously believe A, B, and ¬(A ∧ B), because there is no possible world in which all three are true. With probabilities, however, statements refer not to the world directly, but to the agent’s own state of knowledge. Why, then, can an agent not hold the following set of beliefs (even though they violate Kolmogorov’s axioms)?

P (a) = 0.4 P(a ∧ b) = 0.0

P (b) = 0.3 P(a ∨ b) = 0.8 . (13.5)

This kind of question has been the subject of decades of intense debate between those who advocate the use of probabilities as the only legitimate form for degrees of belief and those who advocate alternative approaches.

One argument for the axioms of probability, first stated in 1931 by Bruno de Finetti (and translated into English in de Finetti (1993)), is as follows: If an agent has some degree of belief in a proposition a, then the agent should be able to state odds at which it is indifferent to a bet for or against a.3 Think of it as a game between two agents: Agent 1 states, “my degree of belief in event a is 0.4.” Agent 2 is then free to choose whether to wager for or against a at stakes that are consistent with the stated degree of belief. That is, Agent 2 could choose to accept Agent 1’s bet that a will occur, offering $6 against Agent 1’s $4. Or Agent 2 could accept Agent 1’s bet that ¬a will occur, offering $4 against Agent 1’s $6. Then we observe the outcome of a, and whoever is right collects the money. If an agent’s degrees of belief do not accurately reflect the world, then you would expect that it would tend to lose money over the long run to an opposing agent whose beliefs more accurately reflect the state of the world.

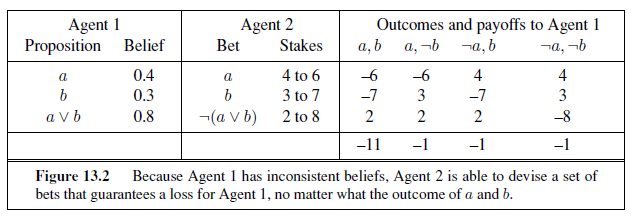

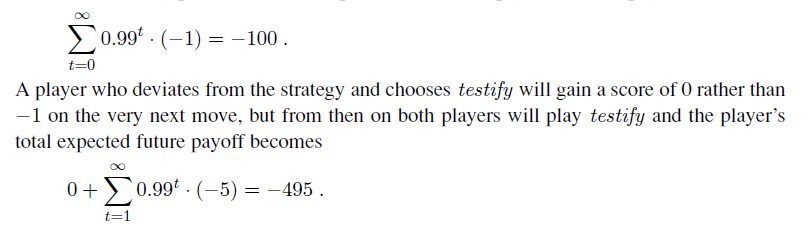

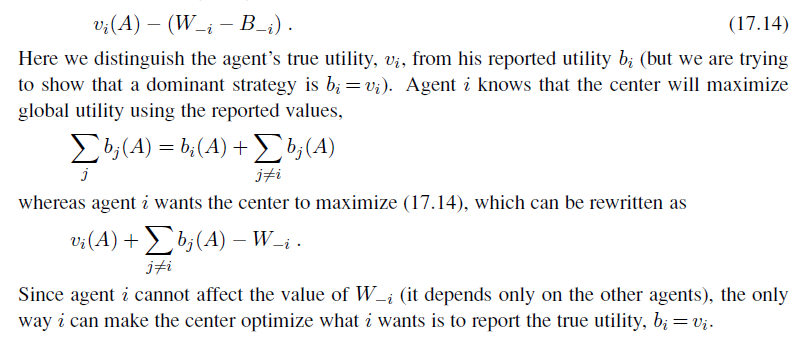

But de Finetti proved something much stronger: If Agent 1 expresses a set of degrees of belief that violate the axioms of probability theory then there is a combination of bets by Agent 2 that guarantees that Agent 1 will lose money every time. For example, suppose that Agent 1 has the set of degrees of belief from Equation (13.5). Figure 13.2 shows that if Agent

2 The difficulties include the Vitali set, a well-defined subset of the interval [0, 1] with no well-defined size. 3 One might argue that the agent’s preferences for different bank balances are such that the possibility of losing $1 is not counterbalanced by an equal possibility of winning $1. One possible response is to make the bet amounts small enough to avoid this problem. Savage’s analysis (1954) circumvents the issue altogether.

2 chooses to bet $4 on a, $3 on b, and $2 on ¬(a ∨ b), then Agent 1 always loses money, regardless of the outcomes for a and b. De Finetti’s theorem implies that no rational agent can have beliefs that violate the axioms of probability.

One common objection to de Finetti’s theorem is that this betting game is rather contrived. For example, what if one refuses to bet? Does that end the argument? The answer is that the betting game is an abstract model for the decision-making situation in which every agent is unavoidably involved at every moment. Every action (including inaction) is a kind of bet, and every outcome can be seen as a payoff of the bet. Refusing to bet is like refusing to allow time to pass.

Other strong philosophical arguments have been put forward for the use of probabilities, most notably those of Cox (1946), Carnap (1950), and Jaynes (2003). They each construct a set of axioms for reasoning with degrees of beliefs: no contradictions, correspondence with ordinary logic (for example, if belief in A goes up, then belief in ¬A must go down), and so on. The only controversial axiom is that degrees of belief must be numbers, or at least act like numbers in that they must be transitive (if belief in A is greater than belief in B, which is greater than belief in C , then belief in A must be greater than C) and comparable (the belief in A must be one of equal to, greater than, or less than belief in B). It can then be proved that probability is the only approach that satisfies these axioms.

The world being the way it is, however, practical demonstrations sometimes speak louder than proofs. The success of reasoning systems based on probability theory has been much more effective in making converts. We now look at how the axioms can be deployed to make inferences.

INFERENCE USING FULL JOINT DISTRIBUTIONS

In this section we describe a simple method for probabilistic inference—that is, the computation of posterior probabilities for query propositions given observed evidence. We use the full joint distribution as the “knowledge base” from which answers to all questions may be derived. Along the way we also introduce several useful techniques for manipulating equations involving probabilities.

WHERE DO PROBABILITIES COME FROM?

There has been endless debate over the source and status of probability numbers. The frequentist position is that the numbers can come only from experiments: if we test 100 people and find that 10 of them have a cavity, then we can say that the probability of a cavity is approximately 0.1. In this view, the assertion “the probability of a cavity is 0.1” means that 0.1 is the fraction that would be observed in the limit of infinitely many samples. From any finite sample, we can estimate the true fraction and also calculate how accurate our estimate is likely to be.

The objectivist view is that probabilities are real aspects of the universe— propensities of objects to behave in certain ways—rather than being just descriptions of an observer’s degree of belief. For example, the fact that a fair coin comes up heads with probability 0.5 is a propensity of the coin itself. In this view, frequentist measurements are attempts to observe these propensities. Most physicists agree that quantum phenomena are objectively probabilistic, but uncertainty at the macroscopic scale—e.g., in coin tossing—usually arises from ignorance of initial conditions and does not seem consistent with the propensity view.

The subjectivist view describes probabilities as a way of characterizing an agent’s beliefs, rather than as having any external physical significance. The subjective Bayesian view allows any self-consistent ascription of prior probabilities to propositions, but then insists on proper Bayesian updating as evidence arrives.

In the end, even a strict frequentist position involves subjective analysis because of the reference class problem: in trying to determine the outcome probability of a particular experiment, the frequentist has to place it in a reference class of “similar” experiments with known outcome frequencies. I. J. Good (1983, p. 27) wrote, “every event in life is unique, and every real-life probability that we estimate in practice is that of an event that has never occurred before.” For example, given a particular patient, a frequentist who wants to estimate the probability of a cavity will consider a reference class of other patients who are similar in important ways—age, symptoms, diet—and see what proportion of them had a cavity. If the dentist considers everything that is known about the patient—weight to the nearest gram, hair color, mother’s maiden name—then the reference class becomes empty. This has been a vexing problem in the philosophy of science.

The principle of indifference attributed to Laplace (1816) states that propositions that are syntactically “symmetric” with respect to the evidence should be accorded equal probability. Various refinements have been proposed, culminating in the attempt by Carnap and others to develop a rigorous inductive logic, capable of computing the correct probability for any proposition from any collection of observations. Currently, it is believed that no unique inductive logic exists; rather, any such logic rests on a subjective prior probability distribution whose effect is diminished as more observations are collected.

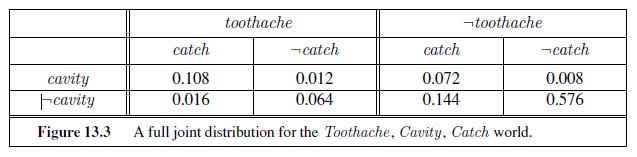

We begin with a simple example: a domain consisting of just the three Boolean variables Toothache , Cavity , and Catch (the dentist’s nasty steel probe catches in my tooth). The full joint distribution is a 2× 2× 2 table as shown in Figure 13.3.

Notice that the probabilities in the joint distribution sum to 1, as required by the axioms of probability. Notice also that Equation (13.2) gives us a direct way to calculate the probability of any proposition, simple or complex: simply identify those possible worlds in which the proposition is true and add up their probabilities. For example, there are six possible worlds in which cavity ∨ toothache holds:

P (cavity ∨ toothache) = 0.108 + 0.012 + 0.072 + 0.008 + 0.016 + 0.064 = 0.28 .

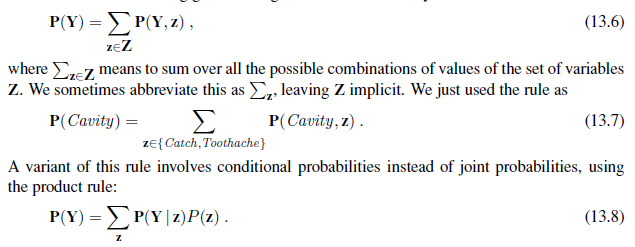

One particularly common task is to extract the distribution over some subset of variables or a single variable. For example, adding the entries in the first row gives the unconditional or marginal probability4 of cavity :

P (cavity) = 0.108 + 0.012 + 0.072 + 0.008 = 0.2 .

This process is called marginalization, or summing out—because we sum up the probabilities for each possible value of the other variables, thereby taking them out of the equation. We can write the following general marginalization rule for any sets of variables Y and Z:

This rule is called conditioning. Marginalization and conditioning turn out to be useful rules for all kinds of derivations involving probability expressions. In most cases, we are interested in computing conditional probabilities of some variables, given evidence about others. Conditional probabilities can be found by first using

4 So called because of a common practice among actuaries of writing the sums of observed frequencies in the margins of insurance tables.

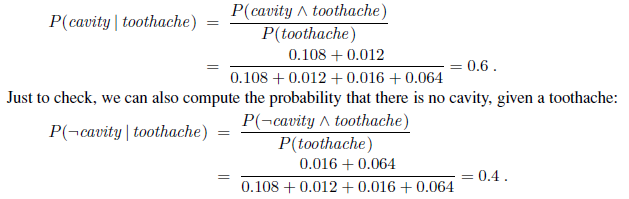

Equation (13.3) to obtain an expression in terms of unconditional probabilities and then evaluating the expression from the full joint distribution. For example, we can compute the probability of a cavity, given evidence of a toothache, as follows:

The two values sum to 1.0, as they should. Notice that in these two calculations the term 1/P (toothache ) remains constant, no matter which value of Cavity we calculate. In fact, it can be viewed as a normalization constant for the distribution P(Cavity | toothache), ensuring that it adds up to 1. Throughout the chapters dealing with probability, we use α to denote such constants. With this notation, we can write the two preceding equations in one:

P(Cavity | toothache) = α P(Cavity , toothache) = α [P(Cavity , toothache , catch) + P(Cavity , toothache ,¬catch)] = α [〈0.108, 0.016〉+ 〈0.012, 0.064〉] = α 〈0.12, 0.08〉 = 〈0.6, 0.4〉 .

In other words, we can calculate P(Cavity | toothache) even if we don’t know the value of P (toothache)! We temporarily forget about the factor 1/P (toothache ) and add up the values for cavity and ¬cavity , getting 0.12 and 0.08. Those are the correct relative proportions, but they don’t sum to 1, so we normalize them by dividing each one by 0.12 + 0.08, getting the true probabilities of 0.6 and 0.4. Normalization turns out to be a useful shortcut in many probability calculations, both to make the computation easier and to allow us to proceed when some probability assessment (such as P (toothache)) is not available.

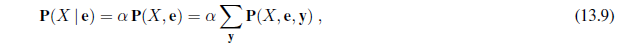

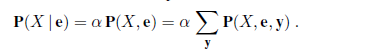

From the example, we can extract a general inference procedure. We begin with the case in which the query involves a single variable, X (Cavity in the example). Let E be the list of evidence variables (just Toothache in the example), let e be the list of observed values for them, and let Y be the remaining unobserved variables (just Catch in the example). The query is P(X | e) and can be evaluated as

where the summation is over all possible ys (i.e., all possible combinations of values of the unobserved variables Y). Notice that together the variables X, E, and Y constitute the complete set of variables for the domain, so P(X, e, y) is simply a subset of probabilities from the full joint distribution.

Given the full joint distribution to work with, Equation (13.9) can answer probabilistic queries for discrete variables. It does not scale well, however: for a domain described by n Boolean variables, it requires an input table of size O(2^n^) and takes O(2^n^) time to process the table. In a realistic problem we could easily have n > 100, making O(2^n^) impractical. The full joint distribution in tabular form is just not a practical tool for building reasoning systems. Instead, it should be viewed as the theoretical foundation on which more effective approaches may be built, just as truth tables formed a theoretical foundation for more practical algorithms like DPLL. The remainder of this chapter introduces some of the basic ideas required in preparation for the development of realistic systems in Chapter 14.

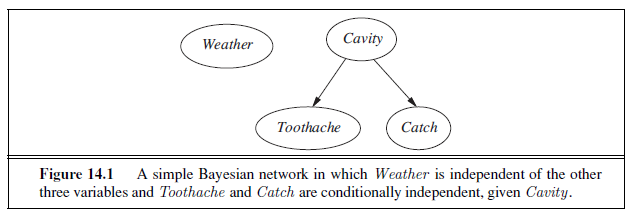

INDEPENDENCE

Let us expand the full joint distribution in Figure 13.3 by adding a fourth variable, Weather . The full joint distribution then becomes P(Toothache ,Catch,Cavity ,Weather ), which has 2 × 2 × 2 × 4 = 32 entries. It contains four “editions” of the table shown in Figure 13.3, one for each kind of weather. What relationship do these editions have to each other and to the original three-variable table? For example, how are P (toothache , catch , cavity , cloudy)

and P(toothache , catch , cavity) related? We can use the product rule:

P (toothache , catch , cavity , cloudy)

= P (cloudy | toothache , catch , cavity) P(toothache , catch , cavity) .

Now, unless one is in the deity business, one should not imagine that one’s dental problems influence the weather. And for indoor dentistry, at least, it seems safe to say that the weather does not influence the dental variables. Therefore, the following assertion seems reasonable:

P (cloudy | toothache , catch , cavity) = P (cloudy) . (13.10)

From this, we can deduce

P (toothache , catch , cavity , cloudy) = P (cloudy)P (toothache , catch , cavity) .

A similar equation exists for every entry in P(Toothache ,Catch ,Cavity ,Weather ). In fact, we can write the general equation

P(Toothache ,Catch ,Cavity ,Weather ) = P(Toothache ,Catch,Cavity)P(Weather ) .

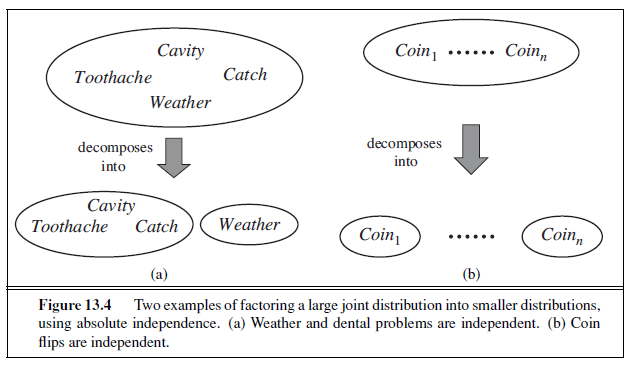

Thus, the 32-element table for four variables can be constructed from one 8-element table and one 4-element table. This decomposition is illustrated schematically in Figure 13.4(a).

The property we used in Equation (13.10) is called independence (also **marginal in-**INDEPENDENCE

dependence and absolute independence). In particular, the weather is independent of one’s dental problems. Independence between propositions a and b can be written as

P (a | b)= P (a) or P (b | a)= P (b) or P (a ∧ b)= P (a) P(b) . (13.11)

All these forms are equivalent (Exercise 13.12). Independence between variables X and Y

can be written as follows (again, these are all equivalent):

P(X |Y )= P(X) or P(Y |X)= P(Y ) or P(X,Y )= P(X)P(Y ) .

Independence assertions are usually based on knowledge of the domain. As the toothache– weather example illustrates, they can dramatically reduce the amount of information necessary to specify the full joint distribution. If the complete set of variables can be divided

into independent subsets, then the full joint distribution can be factored into separate joint distributions on those subsets. For example, the full joint distribution on the outcome of n independent coin flips, P(C~1~, . . . , C~n~), has 2^n^ entries, but it can be represented as the product of n single-variable distributions P(Ci). In a more practical vein, the independence of dentistry and meteorology is a good thing, because otherwise the practice of dentistry might require intimate knowledge of meteorology, and vice versa.

When they are available, then, independence assertions can help in reducing the size of the domain representation and the complexity of the inference problem. Unfortunately, clean separation of entire sets of variables by independence is quite rare. Whenever a connection, however indirect, exists between two variables, independence will fail to hold. Moreover, even independent subsets can be quite large—for example, dentistry might involve dozens of diseases and hundreds of symptoms, all of which are interrelated. To handle such problems, we need more subtle methods than the straightforward concept of independence.

BAYES’ RULE AND ITS USE

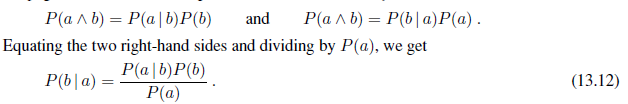

On page 486, we defined the product rule. It can actually be written in two forms:

This equation is known as Bayes’ rule (also Bayes’ law or Bayes’ theorem). This simple equation underlies most modern AI systems for probabilistic inference.

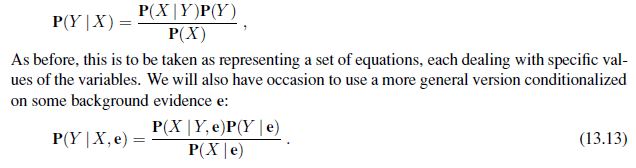

The more general case of Bayes’ rule for multivalued variables can be written in the P notation as follows:

Applying Bayes’ rule: The simple case

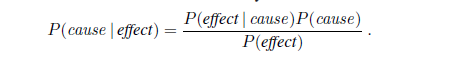

On the surface, Bayes’ rule does not seem very useful. It allows us to compute the single term P (b | a) in terms of three terms: P (a | b), P (b), and P (a). That seems like two steps backwards, but Bayes’ rule is useful in practice because there are many cases where we do have good probability estimates for these three numbers and need to compute the fourth. Often, we perceive as evidence the effect of some unknown cause and we would like to determine that cause. In that case, Bayes’ rule becomes

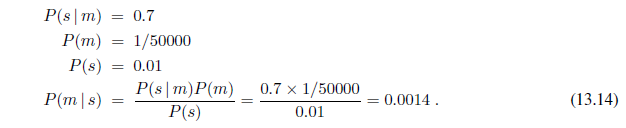

The conditional probability P (effect | cause) quantifies the relationship in the causal direction, whereas P (cause | effect) describes the diagnostic direction. In a task such as medical diagnosis, we often have conditional probabilities on causal relationships (that is, the doctor knows P (symptoms | disease)) and want to derive a diagnosis, P (disease | symptoms). For example, a doctor knows that the disease meningitis causes the patient to have a stiff neck, say, 70% of the time. The doctor also knows some unconditional facts: the prior probability that a patient has meningitis is 1/50,000, and the prior probability that any patient has a stiff neck is 1%. Letting s be the proposition that the patient has a stiff neck and m be the proposition that the patient has meningitis, we have

That is, we expect less than 1 in 700 patients with a stiff neck to have meningitis. Notice that even though a stiff neck is quite strongly indicated by meningitis (with probability 0.7), the probability of meningitis in the patient remains small. This is because the prior probability of stiff necks is much higher than that of meningitis.

Section 13.3 illustrated a process by which one can avoid assessing the prior probability of the evidence (here, P (s)) by instead computing a posterior probability for each value of the query variable (here, m and ¬m) and then normalizing the results. The same process can be applied when using Bayes’ rule. We have

P(M | s) = α 〈P (s | m) P (m), P (s | ¬m) P (¬m)〉 .

Thus, to use this approach we need to estimate P (s | ¬m) instead of P (s). There is no free lunch—sometimes this is easier, sometimes it is harder. The general form of Bayes’ rule with normalization is

P(Y | X) = α P(X |Y )P(Y ) , (13.15)

where α is the normalization constant needed to make the entries in P(Y |X) sum to 1. One obvious question to ask about Bayes’ rule is why one might have available the conditional probability in one direction, but not the other. In the meningitis domain, perhaps the doctor knows that a stiff neck implies meningitis in 1 out of 5000 cases; that is, the doctor has quantitative information in the diagnostic direction from symptoms to causes. Such a doctor has no need to use Bayes’ rule. Unfortunately, diagnostic knowledge is often more fragile than causal knowledge. If there is a sudden epidemic of meningitis, the unconditional probability of meningitis, P (m), will go up. The doctor who derived the diagnostic probability P (m | s) directly from statistical observation of patients before the epidemic will have no idea how to update the value, but the doctor who computes P (m | s) from the other three values will see that P (m | s) should go up proportionately with P (m). Most important, the causal information P (s |m) is unaffected by the epidemic, because it simply reflects the way meningitis works. The use of this kind of direct causal or model-based knowledge provides the crucial robustness needed to make probabilistic systems feasible in the real world.

Using Bayes’ rule: Combining evidence

We have seen that Bayes’ rule can be useful for answering probabilistic queries conditioned on one piece of evidence—for example, the stiff neck. In particular, we have argued that probabilistic information is often available in the form P (effect | cause). What happens when we have two or more pieces of evidence? For example, what can a dentist conclude if her nasty steel probe catches in the aching tooth of a patient? If we know the full joint distribution (Figure 13.3), we can read off the answer:

P(Cavity | toothache ∧ catch) = α 〈0.108, 0.016〉 ≈ 〈0.871, 0.129〉 .

We know, however, that such an approach does not scale up to larger numbers of variables. We can try using Bayes’ rule to reformulate the problem:

P(Cavity | toothache ∧ catch)

= α P(toothache ∧ catch |Cavity) P(Cavity) . (13.16)

For this reformulation to work, we need to know the conditional probabilities of the conjunction toothache ∧catch for each value of Cavity . That might be feasible for just two evidence variables, but again it does not scale up. If there are n possible evidence variables (X rays, diet, oral hygiene, etc.), then there are 2^n^ possible combinations of observed values for which we would need to know conditional probabilities. We might as well go back to using the full joint distribution. This is what first led researchers away from probability theory toward approximate methods for evidence combination that, while giving incorrect answers, require fewer numbers to give any answer at all.

Rather than taking this route, we need to find some additional assertions about the domain that will enable us to simplify the expressions. The notion of independence in Section 13.4 provides a clue, but needs refining. It would be nice if Toothache and Catch were independent, but they are not: if the probe catches in the tooth, then it is likely that the tooth has a cavity and that the cavity causes a toothache. These variables are independent, however, given the presence or the absence of a cavity. Each is directly caused by the cavity, but neither has a direct effect on the other: toothache depends on the state of the nerves in the tooth, whereas the probe’s accuracy depends on the dentist’s skill, to which the toothache is irrelevant.5 Mathematically, this property is written as

P(toothache ∧ catch | Cavity) = P(toothache | Cavity)P(catch | Cavity) . (13.17)

This equation expresses the conditional independence of toothache and catch given Cavity .

We can plug it into Equation (13.16) to obtain the probability of a cavity:

P(Cavity | toothache ∧ catch) = α P(toothache | Cavity) P(catch | Cavity) P(Cavity) . (13.18)

Now the information requirements are the same as for inference, using each piece of evidence separately: the prior probability P(Cavity) for the query variable and the conditional probability of each effect, given its cause.

The general definition of conditional independence of two variables X and Y , given a third variable Z , is

P(X,Y | Z) = P(X | Z)P(Y | Z) .

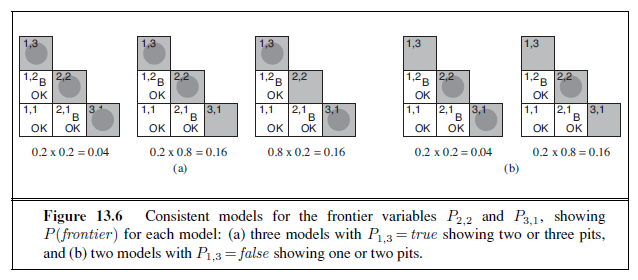

In the dentist domain, for example, it seems reasonable to assert conditional independence of the variables Toothache and Catch , given Cavity :

P(Toothache ,Catch | Cavity) = P(Toothache | Cavity)P(Catch | Cavity) . (13.19)

Notice that this assertion is somewhat stronger than Equation (13.17), which asserts independence only for specific values of Toothache and Catch . As with absolute independence in Equation (13.11), the equivalent forms

P(X | Y,Z)= P(X | Z) and P(Y | X,Z)= P(Y | Z)

can also be used (see Exercise 13.17). Section 13.4 showed that absolute independence assertions allow a decomposition of the full joint distribution into much smaller pieces. It turns out that the same is true for conditional independence assertions. For example, given the assertion in Equation (13.19), we can derive a decomposition as follows:

P(Toothache ,Catch,Cavity)

= P(Toothache ,Catch | Cavity)P(Cavity) (product rule)

= P(Toothache | Cavity)P(Catch | Cavity)P(Cavity) (using 13.19).

(The reader can easily check that this equation does in fact hold in Figure 13.3.) In this way, the original large table is decomposed into three smaller tables. The original table has seven

5 We assume that the patient and dentist are distinct individuals.

independent numbers (23 = 8 entries in the table, but they must sum to 1, so 7 are independent). The smaller tables contain five independent numbers (for a conditional probability distributions such as P(T |C there are two rows of two numbers, and each row sums to 1, so that’s two independent numbers; for a prior distribution like P(C) there is only one independent number). Going from seven to five might not seem like a major triumph, but the point is that, for n symptoms that are all conditionally independent given Cavity , the size of the representation grows as O(n) instead of O(2^n^). That means that conditional independence assertions can allow probabilistic systems to scale up; moreover, they are much more commonly available than absolute independence assertions. Conceptually, Cavity separates Toothache and Catch because it is a direct cause of both of them. The decomposition of large probabilistic domains into weakly connected subsets through conditional independence is one of the most important developments in the recent history of AI.

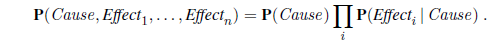

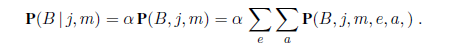

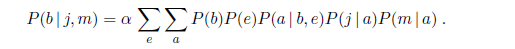

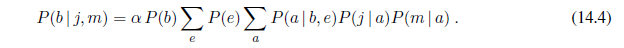

The dentistry example illustrates a commonly occurring pattern in which a single cause directly influences a number of effects, all of which are conditionally independent, given the cause. The full joint distribution can be written as

Such a probability distribution is called a naive Bayes model—“naive” because it is often used (as a simplifying assumption) in cases where the “effect” variables are not actually conditionally independent given the cause variable. (The naive Bayes model is sometimes called a Bayesian classifier, a somewhat careless usage that has prompted true Bayesians to call it the idiot Bayes model.) In practice, naive Bayes systems can work surprisingly well, even when the conditional independence assumption is not true. Chapter 20 describes methods for learning naive Bayes distributions from observations.

THE WUMPUS WORLD REVISITED

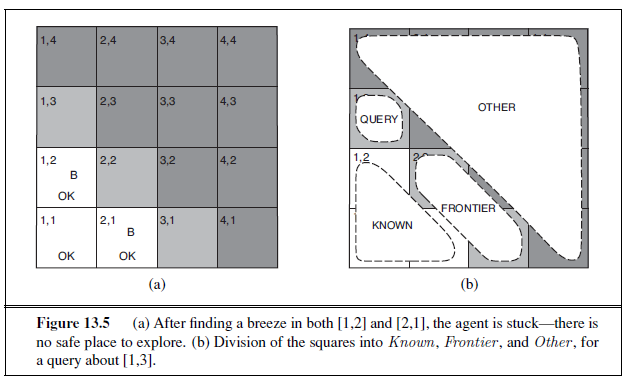

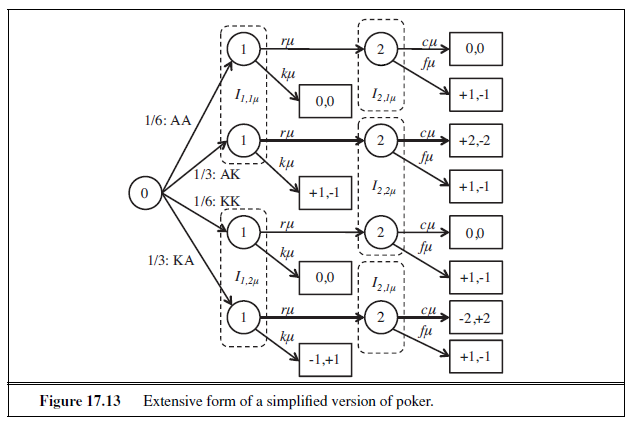

We can combine of the ideas in this chapter to solve probabilistic reasoning problems in the wumpus world. (See Chapter 7 for a complete description of the wumpus world.) Uncertainty arises in the wumpus world because the agent’s sensors give only partial information about the world. For example, Figure 13.5 shows a situation in which each of the three reachable squares—[1,3], [2,2], and [3,1]—might contain a pit. Pure logical inference can conclude nothing about which square is most likely to be safe, so a logical agent might have to choose randomly. We will see that a probabilistic agent can do much better than the logical agent.

Our aim is to calculate the probability that each of the three squares contains a pit. (For this example we ignore the wumpus and the gold.) The relevant properties of the wumpus world are that (1) a pit causes breezes in all neighboring squares, and (2) each square other than [1,1] contains a pit with probability 0.2. The first step is to identify the set of random variables we need:

- As in the propositional logic case, we want one Boolean variable Pij for each square, which is true iff square [i, j] actually contains a pit.

- We also have Boolean variables Bij that are true iff square [i, j] is breezy; we include these variables only for the observed squares—in this case, [1,1], [1,2], and [2,1].

The next step is to specify the full joint distribution, P(P~1,1~, . . . , P~4,4~, B~1,1~, B~1,2~, B~2,1~). Applying the product rule, we have

P(P~1,1~, . . . , P~4,4~, B~1,1~, B~1,2~, B~2,1~) = P(B~1,1~, B~1,2~, B~2,1~ | P~1,1~, . . . , P~4,4~)P(P~1,1~, . . . , P~4,4~) .

This decomposition makes it easy to see what the joint probability values should be. The first term is the conditional probability distribution of a breeze configuration, given a pit configuration; its values are 1 if the breezes are adjacent to the pits and 0 otherwise. The second term is the prior probability of a pit configuration. Each square contains a pit with probability 0.2, independently of the other squares; hence,

For a particular configuration with exactly n pits, P (P~1,1~, . . . , P~4,4~)= 0.2^n^× 0.816−n. In the situation in Figure 13.5(a), the evidence consists of the observed breeze (or its

absence) in each square that is visited, combined with the fact that each such square contains no pit. We abbreviate these facts as b=¬b~1,1~∧b~1,2~∧b~2,1~ and known =¬P~1,1~∧¬p~1~,2∧¬p~2~,1. We are interested in answering queries such as P(P~1,3~ | known , b): how likely is it that [1,3] contains a pit, given the observations so far?

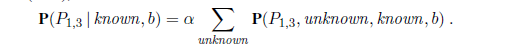

To answer this query, we can follow the standard approach of Equation (13.9), namely, summing over entries from the full joint distribution. Let Unknown be the set of P~i,j~ variables for squares other than the Known squares and the query square [1,3]. Then, by Equation (13.9), we have

The full joint probabilities have already been specified, so we are done—that is, unless we care about computation. There are 12 unknown squares; hence the summation contains 212 = 4096 terms. In general, the summation grows exponentially with the number of squares.

Surely, one might ask, aren’t the other squares irrelevant? How could [4,4] affect whether [1,3] has a pit? Indeed, this intuition is correct. Let Frontier be the pit variables (other than the query variable) that are adjacent to visited squares, in this case just [2,2] and [3,1]. Also, let Other be the pit variables for the other unknown squares; in this case, there are 10 other squares, as shown in Figure 13.5(b). The key insight is that the observed breezes are conditionally independent of the other variables, given the known, frontier, and query variables. To use the insight, we manipulate the query formula into a form in which the breezes are conditioned on all the other variables, and then we apply conditional independence:

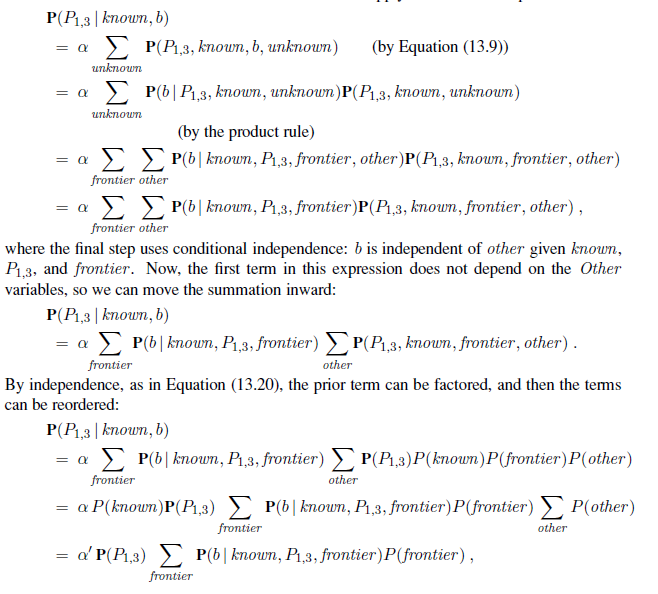

where the last step folds P (known) into the normalizing constant and uses the fact that ∑ other P (other ) equals 1. Now, there are just four terms in the summation over the frontier variables P~2,2~ and P~3,1~. The use of independence and conditional independence has completely eliminated the other squares from consideration.

Notice that the expression P(b | known , P~1,3~, frontier) is 1 when the frontier is consistent with the breeze observations, and 0 otherwise. Thus, for each value of P~1,3~, we sum over the logical models for the frontier variables that are consistent with the known facts. (Compare with the enumeration over models in Figure 7.5 on page 241.) The models and their associated prior probabilities—P (frontier )—are shown in Figure 13.6. We have

P(P~1,3~ | known , b) = α′ 〈0.2(0.04 + 0.16 + 0.16), 0.8(0.04 + 0.16)〉 ≈ 〈0.31, 0.69〉 .

That is, [1,3] (and [3,1] by symmetry) contains a pit with roughly 31% probability. A similar calculation, which the reader might wish to perform, shows that [2,2] contains a pit with roughly 86% probability. The wumpus agent should definitely avoid [2,2]! Note that our logical agent from Chapter 7 did not know that [2,2] was worse than the other squares. Logic can tell us that it is unknown whether there is a pit in [2, 2], but we need probability to tell us how likely it is.

What this section has shown is that even seemingly complicated problems can be formulated precisely in probability theory and solved with simple algorithms. To get efficient solutions, independence and conditional independence relationships can be used to simplify the summations required. These relationships often correspond to our natural understanding of how the problem should be decomposed. In the next chapter, we develop formal representations for such relationships as well as algorithms that operate on those representations to perform probabilistic inference efficiently.

SUMMARY

This chapter has suggested probability theory as a suitable foundation for uncertain reasoning and provided a gentle introduction to its use.

-

Uncertainty arises because of both laziness and ignorance. It is inescapable in complex, nondeterministic, or partially observable environments.

-

Probabilities express the agent’s inability to reach a definite decision regarding the truth of a sentence. Probabilities summarize the agent’s beliefs relative to the evidence.

-

Decision theory combines the agent’s beliefs and desires, defining the best action as the one that maximizes expected utility.

-

Basic probability statements include prior probabilities and conditional probabilities over simple and complex propositions.

-

The axioms of probability constrain the possible assignments of probabilities to propositions. An agent that violates the axioms must behave irrationally in some cases.

-

The full joint probability distribution specifies the probability of each complete assignment of values to random variables. It is usually too large to create or use in its explicit form, but when it is available it can be used to answer queries simply by adding up entries for the possible worlds corresponding to the query propositions.

-

Absolute independence between subsets of random variables allows the full joint distribution to be factored into smaller joint distributions, greatly reducing its complexity. Absolute independence seldom occurs in practice.

-

Bayes’ rule allows unknown probabilities to be computed from known conditional probabilities, usually in the causal direction. Applying Bayes’ rule with many pieces of evidence runs into the same scaling problems as does the full joint distribution.

-

Conditional independence brought about by direct causal relationships in the domain might allow the full joint distribution to be factored into smaller, conditional distributions. The naive Bayes model assumes the conditional independence of all effect variables, given a single cause variable, and grows linearly with the number of effects.

-

A wumpus-world agent can calculate probabilities for unobserved aspects of the world, thereby improving on the decisions of a purely logical agent. Conditional independence makes these calculations tractable.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL NOTES

Probability theory was invented as a way of analyzing games of chance. In about 850 A.D. the Indian mathematician Mahaviracarya described how to arrange a set of bets that can’t lose (what we now call a Dutch book). In Europe, the first significant systematic analyses were produced by Girolamo Cardano around 1565, although publication was posthumous (1663). By that time, probability had been established as a mathematical discipline due to a series of results established in a famous correspondence between Blaise Pascal and Pierre de Fermat in 1654. As with probability itself, the results were initially motivated by gambling problems (see Exercise 13.9). The first published textbook on probability was De Ratiociniis in Ludo Aleae (Huygens, 1657). The “laziness and ignorance” view of uncertainty was described by John Arbuthnot in the preface of his translation of Huygens (Arbuthnot, 1692): “It is impossible for a Die, with such determin’d force and direction, not to fall on such determin’d side, only I don’t know the force and direction which makes it fall on such determin’d side, and therefore I call it Chance, which is nothing but the want of art…”

Laplace (1816) gave an exceptionally accurate and modern overview of probability; he was the first to use the example “take two urns, A and B, the first containing four white and two black balls, . . . ” The Rev. Thomas Bayes (1702–1761) introduced the rule for reasoning about conditional probabilities that was named after him (Bayes, 1763). Bayes only considered the case of uniform priors; it was Laplace who independently developed the general case. Kolmogorov (1950, first published in German in 1933) presented probability theory in a rigorously axiomatic framework for the first time. Rényi (1970) later gave an axiomatic presentation that took conditional probability, rather than absolute probability, as primitive.

Pascal used probability in ways that required both the objective interpretation, as a property of the world based on symmetry or relative frequency, and the subjective interpretation, based on degree of belief—the former in his analyses of probabilities in games of chance, the latter in the famous “Pascal’s wager” argument about the possible existence of God. However, Pascal did not clearly realize the distinction between these two interpretations. The distinction was first drawn clearly by James Bernoulli (1654–1705).

Leibniz introduced the “classical” notion of probability as a proportion of enumerated, equally probable cases, which was also used by Bernoulli, although it was brought to prominence by Laplace (1749–1827). This notion is ambiguous between the frequency interpretation and the subjective interpretation. The cases can be thought to be equally probable either because of a natural, physical symmetry between them, or simply because we do not have any knowledge that would lead us to consider one more probable than another. The use of this latter, subjective consideration to justify assigning equal probabilities is known as the principle of indifference. The principle is often attributed to Laplace, but he never isolated the principle explicitly. George Boole and John Venn both referred to it as the principle of insufficient reason; the modern name is due to Keynes (1921).

The debate between objectivists and subjectivists became sharper in the 20th century. Kolmogorov (1963), R. A. Fisher (1922), and Richard von Mises (1928) were advocates of the relative frequency interpretation. Karl Popper’s (1959, first published in German in 1934) “propensity” interpretation traces relative frequencies to an underlying physical symmetry. Frank Ramsey (1931), Bruno de Finetti (1937), R. T. Cox (1946), Leonard Savage (1954), Richard Jeffrey (1983), and E. T. Jaynes (2003) interpreted probabilities as the degrees of belief of specific individuals. Their analyses of degree of belief were closely tied to utilities and to behavior—specifically, to the willingness to place bets. Rudolf Carnap, following Leibniz and Laplace, offered a different kind of subjective interpretation of probability— not as any actual individual’s degree of belief, but as the degree of belief that an idealized individual should have in a particular proposition a, given a particular body of evidence e.

Carnap attempted to go further than Leibniz or Laplace by making this notion of degree of confirmation mathematically precise, as a logical relation between a and e. The study of this relation was intended to constitute a mathematical discipline called inductive logic, analogous to ordinary deductive logic (Carnap, 1948, 1950). Carnap was not able to extend his inductive logic much beyond the propositional case, and Putnam (1963) showed by adversarial arguments that some fundamental difficulties would prevent a strict extension to languages capable of expressing arithmetic.

Cox’s theorem (1946) shows that any system for uncertain reasoning that meets his set of assumptions is equivalent to probability theory. This gave renewed confidence to those who already favored probability, but others were not convinced, pointing to the assumptions (primarily that belief must be represented by a single number, and thus the belief in ¬p must be a function of the belief in p). Halpern (1999) describes the assumptions and shows some gaps in Cox’s original formulation. Horn (2003) shows how to patch up the difficulties. Jaynes (2003) has a similar argument that is easier to read.

The question of reference classes is closely tied to the attempt to find an inductive logic. The approach of choosing the “most specific” reference class of sufficient size was formally proposed by Reichenbach (1949). Various attempts have been made, notably by Henry Kyburg (1977, 1983), to formulate more sophisticated policies in order to avoid some obvious fallacies that arise with Reichenbach’s rule, but such approaches remain somewhat ad hoc. More recent work by Bacchus, Grove, Halpern, and Koller (1992) extends Carnap’s methods to first-order theories, thereby avoiding many of the difficulties associated with the straightforward reference-class method. Kyburg and Teng (2006) contrast probabilistic inference with nonmonotonic logic.

Bayesian probabilistic reasoning has been used in AI since the 1960s, especially in medical diagnosis. It was used not only to make a diagnosis from available evidence, but also to select further questions and tests by using the theory of information value (Section 16.6) when available evidence was inconclusive (Gorry, 1968; Gorry et al., 1973). One system outperformed human experts in the diagnosis of acute abdominal illnesses (de Dombal et al., 1974). Lucas et al. (2004) gives an overview. These early Bayesian systems suffered from a number of problems, however. Because they lacked any theoretical model of the conditions they were diagnosing, they were vulnerable to unrepresentative data occurring in situations for which only a small sample was available (de Dombal et al., 1981). Even more fundamentally, because they lacked a concise formalism (such as the one to be described in Chapter 14) for representing and using conditional independence information, they depended on the acquisition, storage, and processing of enormous tables of probabilistic data. Because of these difficulties, probabilistic methods for coping with uncertainty fell out of favor in AI from the 1970s to the mid-1980s. Developments since the late 1980s are described in the next chapter.

The naive Bayes model for joint distributions has been studied extensively in the pattern recognition literature since the 1950s (Duda and Hart, 1973). It has also been used, often unwittingly, in information retrieval, beginning with the work of Maron (1961). The probabilistic foundations of this technique, described further in Exercise 13.22, were elucidated by Robertson and Sparck Jones (1976). Domingos and Pazzani (1997) provide an explanation for the surprising success of naive Bayesian reasoning even in domains where the independence assumptions are clearly violated.

There are many good introductory textbooks on probability theory, including those by Bertsekas and Tsitsiklis (2008) and Grinstead and Snell (1997). DeGroot and Schervish (2001) offer a combined introduction to probability and statistics from a Bayesian standpoint. Richard Hamming’s (1991) textbook gives a mathematically sophisticated introduction to probability theory from the standpoint of a propensity interpretation based on physical symmetry. Hacking (1975) and Hald (1990) cover the early history of the concept of probability. Bernstein (1996) gives an entertaining popular account of the story of risk.

EXERCISES

13.1 Show from first principles that P (a | b ∧ a) = 1.

13.2 Using the axioms of probability, prove that any probability distribution on a discrete random variable must sum to 1.

13.3 For each of the following statements, either prove it is true or give a counterexample.

a. If P (a | b, c) = P (b | a, c), then P (a | c) = P (b | c)

b. If P (a | b, c) = P (a), then P (b | c) = P (b)

c. If P (a | b) = P (a), then P (a | b, c) = P (a | c)

13.4 Would it be rational for an agent to hold the three beliefs P (A)= 0.4, P (B)= 0.3, and P (A∨B)=0.5? If so, what range of probabilities would be rational for the agent to hold for A∧B? Make up a table like the one in Figure 13.2, and show how it supports your argument about rationality. Then draw another version of the table where P (A ∨ B)= 0.7. Explain why it is rational to have this probability, even though the table shows one case that is a loss and three that just break even. (Hint: what is Agent 1 committed to about the probability of each of the four cases, especially the case that is a loss?)

13.5 This question deals with the properties of possible worlds, defined on page 488 as assignments to all random variables. We will work with propositions that correspond to exactly one possible world because they pin down the assignments of all the variables. In probability theory, such propositions are called atomic events. For example, with BooleanATOMIC EVENT

variables X~1~, X~2~, X~3~, the proposition x~1~ ∧ ¬x~2~ ∧ ¬x~3~ fixes the assignment of the variables; in the language of propositional logic, we would say it has exactly one model.

a. Prove, for the case of n Boolean variables, that any two distinct atomic events are mutually exclusive; that is, their conjunction is equivalent to false .

b. Prove that the disjunction of all possible atomic events is logically equivalent to true .

c. Prove that any proposition is logically equivalent to the disjunction of the atomic events that entail its truth.

13.6 Prove Equation (13.4) from Equations (13.1) and (13.2).

13.7 Consider the set of all possible five-card poker hands dealt fairly from a standard deck of fifty-two cards.

a. How many atomic events are there in the joint probability distribution (i.e., how many five-card hands are there)?

b. What is the probability of each atomic event?

c. What is the probability of being dealt a royal straight flush? Four of a kind?

13.8 Given the full joint distribution shown in Figure 13.3, calculate the following:

a. P(toothache) .

b. P(Cavity) .

c. P(Toothache | cavity) .

d. P(Cavity | toothache ∨ catch) .

13.9 In his letter of August 24, 1654, Pascal was trying to show how a pot of money should be allocated when a gambling game must end prematurely. Imagine a game where each turn consists of the roll of a die, player E gets a point when the die is even, and player O gets a point when the die is odd. The first player to get 7 points wins the pot. Suppose the game is interrupted with E leading 4–2. How should the money be fairly split in this case? What is the general formula? (Fermat and Pascal made several errors before solving the problem, but you should be able to get it right the first time.)

13.10 Deciding to put probability theory to good use, we encounter a slot machine with three independent wheels, each producing one of the four symbols BAR, BELL, LEMON, or CHERRY with equal probability. The slot machine has the following payout scheme for a bet of 1 coin (where “?” denotes that we don’t care what comes up for that wheel):

BAR/BAR/BAR pays 20 coins BELL/BELL/BELL pays 15 coins LEMON/LEMON/LEMON pays 5 coins CHERRY/CHERRY/CHERRY pays 3 coins CHERRY/CHERRY/? pays 2 coins CHERRY/?/? pays 1 coin

a. Compute the expected “payback” percentage of the machine. In other words, for each coin played, what is the expected coin return?

b. Compute the probability that playing the slot machine once will result in a win.

c. Estimate the mean and median number of plays you can expect to make until you go broke, if you start with 10 coins. You can run a simulation to estimate this, rather than trying to compute an exact answer.

13.11 We wish to transmit an n-bit message to a receiving agent. The bits in the message are independently corrupted (flipped) during transmission with ε probability each. With an extra parity bit sent along with the original information, a message can be corrected by the receiver if at most one bit in the entire message (including the parity bit) has been corrupted. Suppose we want to ensure that the correct message is received with probability at least 1− δ. What is the maximum feasible value of n? Calculate this value for the case ε= 0.001, δ = 0.01.

13.12 Show that the three forms of independence in Equation (13.11) are equivalent.

13.13 Consider two medical tests, A and B, for a virus. Test A is 95% effective at recognizing the virus when it is present, but has a 10% false positive rate (indicating that the virus is present, when it is not). Test B is 90% effective at recognizing the virus, but has a 5% false positive rate. The two tests use independent methods of identifying the virus. The virus is carried by 1% of all people. Say that a person is tested for the virus using only one of the tests, and that test comes back positive for carrying the virus. Which test returning positive is more indicative of someone really carrying the virus? Justify your answer mathematically.

13.14 Suppose you are given a coin that lands heads with probability x and tails with probability 1 − x. Are the outcomes of successive flips of the coin independent of each other given that you know the value of x? Are the outcomes of successive flips of the coin independent of each other if you do not know the value of x? Justify your answer.

13.15 After your yearly checkup, the doctor has bad news and good news. The bad news is that you tested positive for a serious disease and that the test is 99% accurate (i.e., the probability of testing positive when you do have the disease is 0.99, as is the probability of testing negative when you don’t have the disease). The good news is that this is a rare disease, striking only 1 in 10,000 people of your age. Why is it good news that the disease is rare? What are the chances that you actually have the disease?

13.16 It is quite often useful to consider the effect of some specific propositions in the context of some general background evidence that remains fixed, rather than in the complete absence of information. The following questions ask you to prove more general versions of the product rule and Bayes’ rule, with respect to some background evidence e:

a. Prove the conditionalized version of the general product rule:

P(X,Y | e) = P(X | Y, e)P(Y | e) .

b. Prove the conditionalized version of Bayes’ rule in Equation (13.13).

13.17 Show that the statement of conditional independence

P(X,Y | Z) = P(X | Z)P(Y | Z)

is equivalent to each of the statements

P(X | Y,Z) = P(X | Z) and P(B | X,Z) = P(Y | Z) .

13.18 Suppose you are given a bag containing n unbiased coins. You are told that n− 1 of these coins are normal, with heads on one side and tails on the other, whereas one coin is a fake, with heads on both sides.

a. Suppose you reach into the bag, pick out a coin at random, flip it, and get a head. What is the (conditional) probability that the coin you chose is the fake coin?

b. Suppose you continue flipping the coin for a total of k times after picking it and see k heads. Now what is the conditional probability that you picked the fake coin? c. Suppose you wanted to decide whether the chosen coin was fake by flipping it k times.

The decision procedure returns fake if all k flips come up heads; otherwise it returns normal . What is the (unconditional) probability that this procedure makes an error?

13.19 In this exercise, you will complete the normalization calculation for the meningitis example. First, make up a suitable value for P (s | ¬m), and use it to calculate unnormalized values for P (m | s) and P (¬m | s) (i.e., ignoring the P (s) term in the Bayes’ rule expression, Equation (13.14)). Now normalize these values so that they add to 1.

13.20 Let X, Y , Z be Boolean random variables. Label the eight entries in the joint distribution P(X,Y,Z) as a through h. Express the statement that X and Y are conditionally independent given Z , as a set of equations relating a through h. How many nonredundant equations are there?

13.21 (Adapted from Pearl (1988).) Suppose you are a witness to a nighttime hit-and-run accident involving a taxi in Athens. All taxis in Athens are blue or green. You swear, under oath, that the taxi was blue. Extensive testing shows that, under the dim lighting conditions, discrimination between blue and green is 75% reliable.