SOLVING PROBLEMS BY SEARCHING

In which we see how an agent can find a sequence of actions that achieves its goals when no single action will do.

The simplest agents discussed in Chapter 2 were the reflex agents, which base their actions on a direct mapping from states to actions. Such agents cannot operate well in environments for which this mapping would be too large to store and would take too long to learn. Goal-based agents, on the other hand, consider future actions and the desirability of their outcomes.

This chapter describes one kind of goal-based agent called a problem-solving agent. Problem-solving agents use atomic representations, as described in Section 2.4.7—that is, states of the world are considered as wholes, with no internal structure visible to the problemsolving algorithms. Goal-based agents that use more advanced factored or structured representations are usually called planning agents and are discussed in Chapters 7 and 10.

Our discussion of problem solving begins with precise definitions of problems and their solutions and give several examples to illustrate these definitions. We then describe several general-purpose search algorithms that can be used to solve these problems. We will see several uninformed search algorithms—algorithms that are given no information about the problem other than its definition. Although some of these algorithms can solve any solvable problem, none of them can do so efficiently. Informed search algorithms, on the other hand, can do quite well given some guidance on where to look for solutions.

In this chapter, we limit ourselves to the simplest kind of task environment, for which the solution to a problem is always a fixed sequence of actions. The more general case—where the agent’s future actions may vary depending on future percepts—is handled in Chapter 4.

This chapter uses the concepts of asymptotic complexity (that is, O() notation) and NP-completeness. Readers unfamiliar with these concepts should consult Appendix A.

PROBLEM-SOLVING AGENTS

Intelligent agents are supposed to maximize their performance measure. As we mentioned in Chapter 2, achieving this is sometimes simplified if the agent can adopt a goal and aim at satisfying it. Let us first look at why and how an agent might do this.

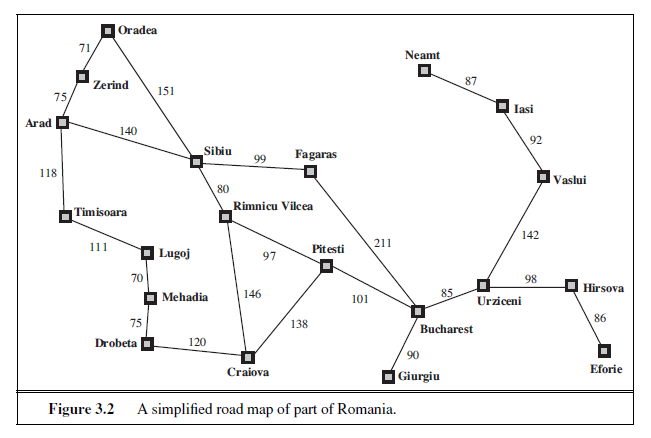

Imagine an agent in the city of Arad, Romania, enjoying a touring holiday. The agent’s performance measure contains many factors: it wants to improve its suntan, improve its Romanian, take in the sights, enjoy the nightlife (such as it is), avoid hangovers, and so on. The decision problem is a complex one involving many tradeoffs and careful reading of guidebooks. Now, suppose the agent has a nonrefundable ticket to fly out of Bucharest the following day. In that case, it makes sense for the agent to adopt the goal of getting to Bucharest. Courses of action that don’t reach Bucharest on time can be rejected without further consideration and the agent’s decision problem is greatly simplified. Goals help organize behavior by limiting the objectives that the agent is trying to achieve and hence the actions it needs to consider. Goal formulation, based on the current situation and the agent’s performance measure, is the first step in problem solving.

We will consider a goal to be a set of world states—exactly those states in which the goal is satisfied. The agent’s task is to find out how to act, now and in the future, so that it reaches a goal state. Before it can do this, it needs to decide (or we need to decide on its behalf) what sorts of actions and states it should consider. If it were to consider actions at the level of “move the left foot forward an inch” or “turn the steering wheel one degree left,” the agent would probably never find its way out of the parking lot, let alone to Bucharest, because at that level of detail there is too much uncertainty in the world and there would be too many steps in a solution. Problem formulation is the process of deciding what actions and states to consider, given a goal. We discuss this process in more detail later. For now, let us assume that the agent will consider actions at the level of driving from one major town to another. Each state therefore corresponds to being in a particular town.

Our agent has now adopted the goal of driving to Bucharest and is considering where to go from Arad. Three roads lead out of Arad, one toward Sibiu, one to Timisoara, and one to Zerind. None of these achieves the goal, so unless the agent is familiar with the geography of Romania, it will not know which road to follow.1 In other words, the agent will not know which of its possible actions is best, because it does not yet know enough about the state that results from taking each action. If the agent has no additional information—i.e., if the environment is unknown in the sense defined in Section 2.3—then it is has no choice but to try one of the actions at random. This sad situation is discussed in Chapter 4.

But suppose the agent has a map of Romania. The point of a map is to provide the agent with information about the states it might get itself into and the actions it can take. The agent can use this information to consider subsequent stages of a hypothetical journey via each of the three towns, trying to find a journey that eventually gets to Bucharest. Once it has found a path on the map from Arad to Bucharest, it can achieve its goal by carrying out the driving actions that correspond to the legs of the journey. In general, an agent with several immediate options of unknown value can decide what to do by first examining future actions that eventually lead to states of known value.

To be more specific about what we mean by “examining future actions,” we have to be more specific about properties of the environment, as defined in Section 2.3. For now,

1 We are assuming that most readers are in the same position and can easily imagine themselves to be as clueless as our agent. We apologize to Romanian readers who are unable to take advantage of this pedagogical device.

we assume that the environment is observable, so the agent always knows the current state. For the agent driving in Romania, it’s reasonable to suppose that each city on the map has a sign indicating its presence to arriving drivers. We also assume the environment is discrete, so at any given state there are only finitely many actions to choose from. This is true for navigating in Romania because each city is connected to a small number of other cities. We will assume the environment is known, so the agent knows which states are reached by each action. (Having an accurate map suffices to meet this condition for navigation problems.) Finally, we assume that the environment is deterministic, so each action has exactly one outcome. Under ideal conditions, this is true for the agent in Romania—it means that if it chooses to drive from Arad to Sibiu, it does end up in Sibiu. Of course, conditions are not always ideal, as we show in Chapter 4.

Under these assumptions, the solution to any problem is a fixed sequence of actions. “Of course!” one might say, “What else could it be?” Well, in general it could be a branching strategy that recommends different actions in the future depending on what percepts arrive. For example, under less than ideal conditions, the agent might plan to drive from Arad to Sibiu and then to Rimnicu Vilcea but may also need to have a contingency plan in case it arrives by accident in Zerind instead of Sibiu. Fortunately, if the agent knows the initial state and the environment is known and deterministic, it knows exactly where it will be after the first action and what it will perceive. Since only one percept is possible after the first action, the solution can specify only one possible second action, and so on.

The process of looking for a sequence of actions that reaches the goal is called search. A search algorithm takes a problem as input and returns a solution in the form of an action sequence. Once a solution is found, the actions it recommends can be carried out. This is called the execution phase. Thus, we have a simple “formulate, search, execute” design for the agent, as shown in Figure 3.1. After formulating a goal and a problem to solve, the agent calls a search procedure to solve it. It then uses the solution to guide its actions, doing whatever the solution recommends as the next thing to do—typically, the first action of the sequence—and then removing that step from the sequence. Once the solution has been executed, the agent will formulate a new goal.

Notice that while the agent is executing the solution sequence it ignores its percepts when choosing an action because it knows in advance what they will be. An agent that carries out its plans with its eyes closed, so to speak, must be quite certain of what is going on. Control theorists call this an open-loop system, because ignoring the percepts breaks the loop between agent and environment. We first describe the process of problem formulation, and then devote the bulk of the chapter to various algorithms for the SEARCH function. We do not discuss the workings of the UPDATE-STATE and FORMULATE-GOAL functions further in this chapter.

Well-defined problems and solutions

A problem can be defined formally by five components:

- The initial state that the agent starts in. For example, the initial state for our agent in Romania might be described as In(Arad).

function SIMPLE-PROBLEM-SOLVING-AGENT(percept ) returns an action

persistent: seq , an action sequence, initially empty

state, some description of the current world state

goal , a goal, initially null

problem , a problem formulation

state←UPDATE-STATE(state,percept )

if seq is empty then

goal← FORMULATE-GOAL(state)

problem← FORMULATE-PROBLEM(state, goal )

seq← SEARCH(problem)

if seq = failure then return a null action

action← FIRST(seq)

seq←REST(seq)

return action

Figure 3.1 A simple problem-solving agent. It first formulates a goal and a problem, searches for a sequence of actions that would solve the problem, and then executes the actions one at a time. When this is complete, it formulates another goal and starts over.

-

A description of the possible actions available to the agent. Given a particular state s,ACTIONS(s) returns the set of actions that can be executed in s. We say that each of these actions is applicable in s. For example, from the state In(Arad), the applicable actions are {Go(Sibiu),Go(Timisoara),Go(Zerind)}.

-

A description of what each action does; the formal name for this is the transition model, specified by a function RESULT(s, a) that returns the state that results from doing action a in state s. We also use the term successor to refer to any state reachable from a given state by a single action.2 For example, we have

RESULT(In(Arad),Go(Zerind)) = In(Zerind) .

Together, the initial state, actions, and transition model implicitly define the state space of the problem—the set of all states reachable from the initial state by any sequence of actions. The state space forms a directed network or graph in which the nodes are states and the links between nodes are actions. (The map of Romania shown in Figure 3.2 can be interpreted as a state-space graph if we view each road as standing for two driving actions, one in each direction.) A path in the state space is a sequence of states connected by a sequence of actions.

- The goal test, which determines whether a given state is a goal state. Sometimes there is an explicit set of possible goal states, and the test simply checks whether the given state is one of them. The agent’s goal in Romania is the singleton set {In(Bucharest)}.

2 Many treatments of problem solving, including previous editions of this book, use a successor function, which returns the set of all successors, instead of separate ACTIONS and RESULT functions. The successor function makes it difficult to describe an agent that knows what actions it can try but not what they achieve. Also, note some author use RESULT(a, s) instead of RESULT(s, a), and some use DO instead of RESULT.

Sometimes the goal is specified by an abstract property rather than an explicitly enumerated set of states. For example, in chess, the goal is to reach a state called “checkmate,” where the opponent’s king is under attack and can’t escape.

- A path cost function that assigns a numeric cost to each path. The problem-solving agent chooses a cost function that reflects its own performance measure. For the agent trying to get to Bucharest, time is of the essence, so the cost of a path might be its length in kilometers. In this chapter, we assume that the cost of a path can be described as the sum of the costs of the individual actions along the path.3 The step cost of taking action a in state s to reach state s ′ is denoted by c(s, a, s′). The step costs for Romania are shown in Figure 3.2 as route distances. We assume that step costs are nonnegative.4

The preceding elements define a problem and can be gathered into a single data structure that is given as input to a problem-solving algorithm. A solution to a problem is an action sequence that leads from the initial state to a goal state. Solution quality is measured by the path cost function, and an optimal solution has the lowest path cost among all solutions.OPTIMAL SOLUTION

Formulating problems

In the preceding section we proposed a formulation of the problem of getting to Bucharest in terms of the initial state, actions, transition model, goal test, and path cost. This formulation seems reasonable, but it is still a model—an abstract mathematical description—and not the 3 This assumption is algorithmically convenient but also theoretically justifiable—see page 649 in Chapter 17. 4 The implications of negative costs are explored in Exercise 3.8. real thing. Compare the simple state description we have chosen, In(Arad), to an actual crosscountry trip, where the state of the world includes so many things: the traveling companions, the current radio program, the scenery out of the window, the proximity of law enforcement officers, the distance to the next rest stop, the condition of the road, the weather, and so on. All these considerations are left out of our state descriptions because they are irrelevant to the problem of finding a route to Bucharest. The process of removing detail from a representation is called abstraction.

In addition to abstracting the state description, we must abstract the actions themselves. A driving action has many effects. Besides changing the location of the vehicle and its occupants, it takes up time, consumes fuel, generates pollution, and changes the agent (as they say, travel is broadening). Our formulation takes into account only the change in location. Also, there are many actions that we omit altogether: turning on the radio, looking out of the window, slowing down for law enforcement officers, and so on. And of course, we don’t specify actions at the level of “turn steering wheel to the left by one degree.”

Can we be more precise about defining the appropriate level of abstraction? Think of the abstract states and actions we have chosen as corresponding to large sets of detailed world states and detailed action sequences. Now consider a solution to the abstract problem: for example, the path from Arad to Sibiu to Rimnicu Vilcea to Pitesti to Bucharest. This abstract solution corresponds to a large number of more detailed paths. For example, we could drive with the radio on between Sibiu and Rimnicu Vilcea, and then switch it off for the rest of the trip. The abstraction is valid if we can expand any abstract solution into a solution in the more detailed world; a sufficient condition is that for every detailed state that is “in Arad,” there is a detailed path to some state that is “in Sibiu,” and so on.5 The abstraction is useful if carrying out each of the actions in the solution is easier than the original problem; in this case they are easy enough that they can be carried out without further search or planning by an average driving agent. The choice of a good abstraction thus involves removing as much detail as possible while retaining validity and ensuring that the abstract actions are easy to carry out. Were it not for the ability to construct useful abstractions, intelligent agents would be completely swamped by the real world.

EXAMPLE PROBLEMS

The problem-solving approach has been applied to a vast array of task environments. We list some of the best known here, distinguishing between toy and real-world problems. A toy problem is intended to illustrate or exercise various problem-solving methods. It can be given a concise, exact description and hence is usable by different researchers to compare the performance of algorithms. A real-world problem is one whose solutions people actually care about. Such problems tend not to have a single agreed-upon description, but we can give the general flavor of their formulations.

5 See Section 11.2 for a more complete set of definitions and algorithms.

Toy problems

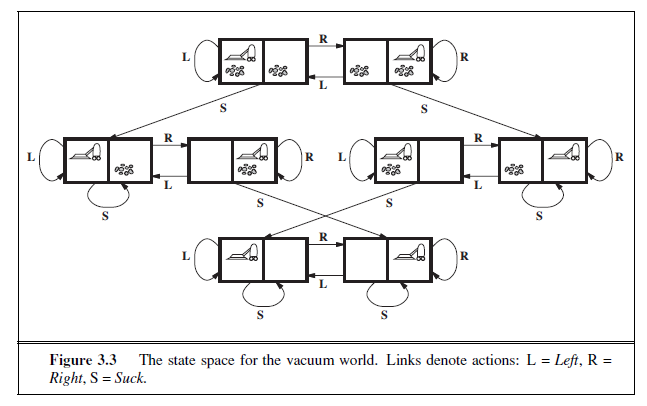

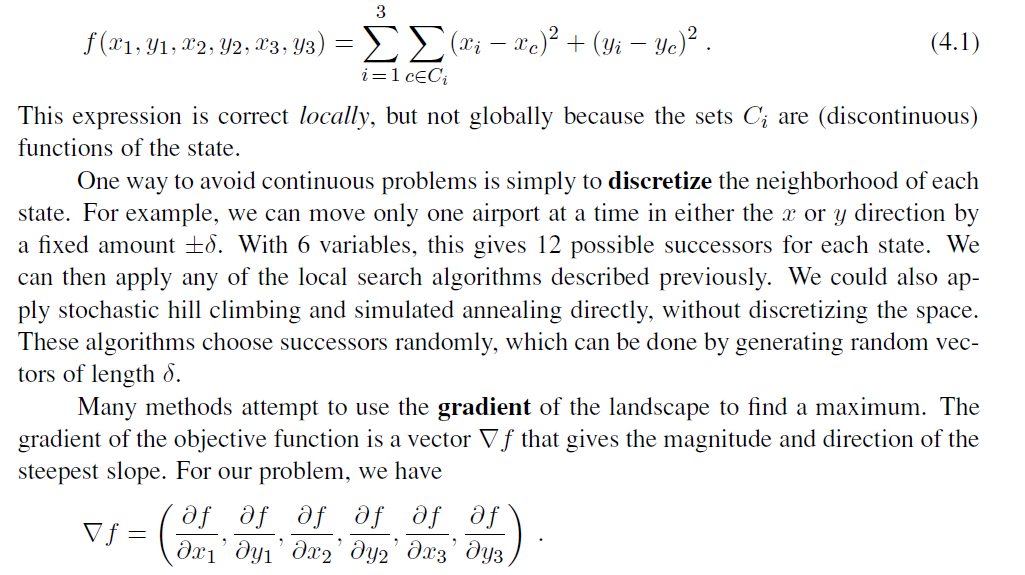

The first example we examine is the vacuum world first introduced in Chapter 2. (See Figure 2.2.) This can be formulated as a problem as follows:

-

States: The state is determined by both the agent location and the dirt locations. The agent is in one of two locations, each of which might or might not contain dirt. Thus, there are 2 × 2^2^ = 8 possible world states. A larger environment with n locations has n · 2^n^ states.

-

Initial state: Any state can be designated as the initial state.

-

Actions: In this simple environment, each state has just three actions: Left, Right, and Suck. Larger environments might also include Up and Down.

-

Transition model: The actions have their expected effects, except that moving Left in the leftmost square, moving Right in the rightmost square, and _Suck_ing in a clean square have no effect. The complete state space is shown in Figure 3.3.

-

Goal test: This checks whether all the squares are clean.

-

Path cost: Each step costs 1, so the path cost is the number of steps in the path.

Compared with the real world, this toy problem has discrete locations, discrete dirt, reliable cleaning, and it never gets any dirtier. Chapter 4 relaxes some of these assumptions.

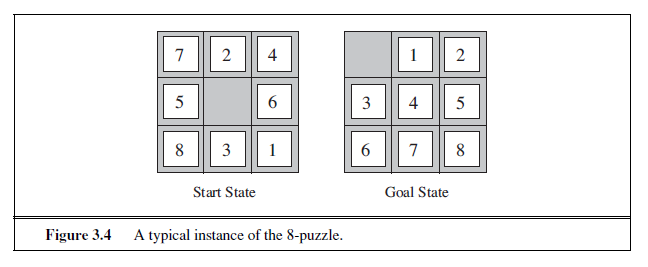

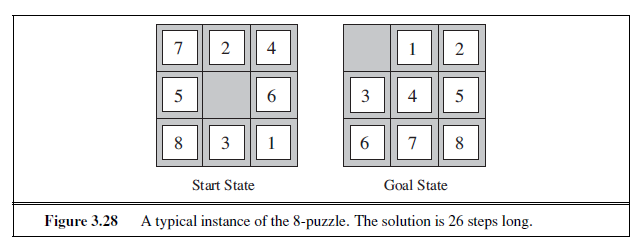

The 8-puzzle, an instance of which is shown in Figure 3.4, consists of a 3×3 board with eight numbered tiles and a blank space. A tile adjacent to the blank space can slide into the space. The object is to reach a specified goal state, such as the one shown on the right of the figure. The standard formulation is as follows:

-

States: A state description specifies the location of each of the eight tiles and the blank in one of the nine squares.

-

Initial state: Any state can be designated as the initial state. Note that any given goal can be reached from exactly half of the possible initial states (Exercise 3.4).

-

Actions: The simplest formulation defines the actions as movements of the blank space Left, Right, Up, or Down. Different subsets of these are possible depending on where the blank is.

-

Transition model: Given a state and action, this returns the resulting state; for example, if we apply Left to the start state in Figure 3.4, the resulting state has the 5 and the blank switched.

-

Goal test: This checks whether the state matches the goal configuration shown in Figure 3.4. (Other goal configurations are possible.)

-

Path cost: Each step costs 1, so the path cost is the number of steps in the path.

What abstractions have we included here? The actions are abstracted to their beginning and final states, ignoring the intermediate locations where the block is sliding. We have abstracted away actions such as shaking the board when pieces get stuck and ruled out extracting the pieces with a knife and putting them back again. We are left with a description of the rules of the puzzle, avoiding all the details of physical manipulations.

The 8-puzzle belongs to the family of sliding-block puzzles, which are often used as test problems for new search algorithms in AI. This family is known to be NP-complete, so one does not expect to find methods significantly better in the worst case than the search algorithms described in this chapter and the next. The 8-puzzle has 9!/2= 181, 440 reachable states and is easily solved. The 15-puzzle (on a 4×4 board) has around 1.3 trillion states, and random instances can be solved optimally in a few milliseconds by the best search algorithms. The 24-puzzle (on a 5 × 5 board) has around 1025 states, and random instances take several hours to solve optimally.

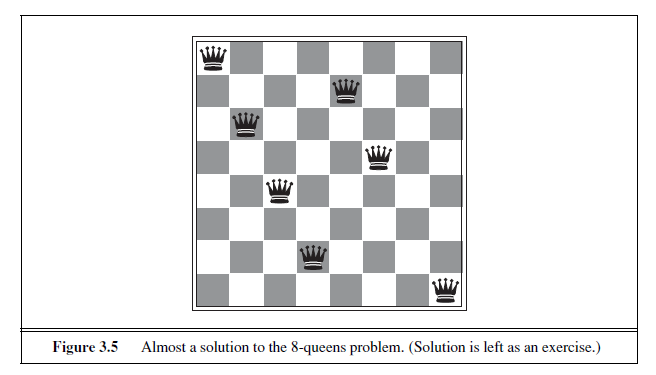

The goal of the 8-queens problem is to place eight queens on a chessboard such that no queen attacks any other. (A queen attacks any piece in the same row, column or diagonal.) Figure 3.5 shows an attempted solution that fails: the queen in the rightmost column is attacked by the queen at the top left.

Although efficient special-purpose algorithms exist for this problem and for the whole n-queens family, it remains a useful test problem for search algorithms. There are two main kinds of formulation. An incremental formulation involves operators that augment the state description, starting with an empty state; for the 8-queens problem, this means that each action adds a queen to the state. A complete-state formulation starts with all 8 queens on the board and moves them around. In either case, the path cost is of no interest because only the final state counts. The first incremental formulation one might try is the following:

-

States: Any arrangement of 0 to 8 queens on the board is a state.

-

Initial state: No queens on the board.

-

Actions: Add a queen to any empty square.

-

Transition model: Returns the board with a queen added to the specified square.

-

Goal test: 8 queens are on the board, none attacked.

In this formulation, we have 64 · 63 · · · 57 ≈ 1.8× 10^14^ possible sequences to investigate. A better formulation would prohibit placing a queen in any square that is already attacked:

-

States: All possible arrangements of n queens (0 ≤ n ≤ 8), one per column in the leftmost n columns, with no queen attacking another.

-

Actions: Add a queen to any square in the leftmost empty column such that it is not attacked by any other queen.

This formulation reduces the 8-queens state space from 1.8× 10^14^ to just 2,057, and solutions are easy to find. On the other hand, for 100 queens the reduction is from roughly 10^400^ states to about 10^52^ states (Exercise 3.5)—a big improvement, but not enough to make the problem tractable. Section 4.1 describes the complete-state formulation, and Chapter 6 gives a simple algorithm that solves even the million-queens problem with ease. Our final toy problem was devised by Donald Knuth (1964) and illustrates how infinite state spaces can arise. Knuth conjectured that, starting with the number 4, a sequence of factorial, square root, and floor operations will reach any desired positive integer. For example, we can reach 5 from 4 as follows:

⌊ √√√√√(4!)!⌋ = 5 .

The problem definition is very simple:

-

States: Positive numbers.

-

Initial state: 4.

-

Actions: Apply factorial, square root, or floor operation (factorial for integers only).

-

Transition model: As given by the mathematical definitions of the operations.

-

Goal test: State is the desired positive integer.

To our knowledge there is no bound on how large a number might be constructed in the process of reaching a given target—for example, the number 620,448,401,733,239,439,360,000 is generated in the expression for 5—so the state space for this problem is infinite. Such state spaces arise frequently in tasks involving the generation of mathematical expressions, circuits, proofs, programs, and other recursively defined objects.

Real-world problems

We have already seen how the route-finding problem is defined in terms of specified locations and transitions along links between them. Route-finding algorithms are used in a variety of applications. Some, such as Web sites and in-car systems that provide driving directions, are relatively straightforward extensions of the Romania example. Others, such as routing video streams in computer networks, military operations planning, and airline travel-planning systems, involve much more complex specifications. Consider the airline travel problems that must be solved by a travel-planning Web site:

-

States: Each state obviously includes a location (e.g., an airport) and the current time. Furthermore, because the cost of an action (a flight segment) may depend on previous segments, their fare bases, and their status as domestic or international, the state must record extra information about these “historical” aspects.

-

Initial state: This is specified by the user’s query.

-

Actions: Take any flight from the current location, in any seat class, leaving after the current time, leaving enough time for within-airport transfer if needed.

-

Transition model: The state resulting from taking a flight will have the flight’s destination as the current location and the flight’s arrival time as the current time.

-

Goal test: Are we at the final destination specified by the user?

-

Path cost: This depends on monetary cost, waiting time, flight time, customs and immigration procedures, seat quality, time of day, type of airplane, frequent-flyer mileage awards, and so on.

Commercial travel advice systems use a problem formulation of this kind, with many additional complications to handle the byzantine fare structures that airlines impose. Any seasoned traveler knows, however, that not all air travel goes according to plan. A really good system should include contingency plans—such as backup reservations on alternate flights— to the extent that these are justified by the cost and likelihood of failure of the original plan.

Touring problems are closely related to route-finding problems, but with an important difference. Consider, for example, the problem “Visit every city in Figure 3.2 at least once, starting and ending in Bucharest.” As with route finding, the actions correspond to trips between adjacent cities. The state space, however, is quite different. Each state must include not just the current location but also the set of cities the agent has visited. So the initial state would be In(Bucharest),Visited({Bucharest}), a typical intermediate state would be In(Vaslui),Visited({Bucharest ,Urziceni ,Vaslui}), and the goal test would check whether the agent is in Bucharest and all 20 cities have been visited.

The traveling salesperson problem (TSP) is a touring problem in which each city must be visited exactly once. The aim is to find the shortest tour. The problem is known to be NP-hard, but an enormous amount of effort has been expended to improve the capabilities of TSP algorithms. In addition to planning trips for traveling salespersons, these algorithms have been used for tasks such as planning movements of automatic circuit-board drills and of stocking machines on shop floors.

A VLSI layout problem requires positioning millions of components and connections on a chip to minimize area, minimize circuit delays, minimize stray capacitances, and maximize manufacturing yield. The layout problem comes after the logical design phase and is usually split into two parts: cell layout and channel routing. In cell layout, the primitive components of the circuit are grouped into cells, each of which performs some recognized function. Each cell has a fixed footprint (size and shape) and requires a certain number of connections to each of the other cells. The aim is to place the cells on the chip so that they do not overlap and so that there is room for the connecting wires to be placed between the cells. Channel routing finds a specific route for each wire through the gaps between the cells. These search problems are extremely complex, but definitely worth solving. Later in this chapter, we present some algorithms capable of solving them.

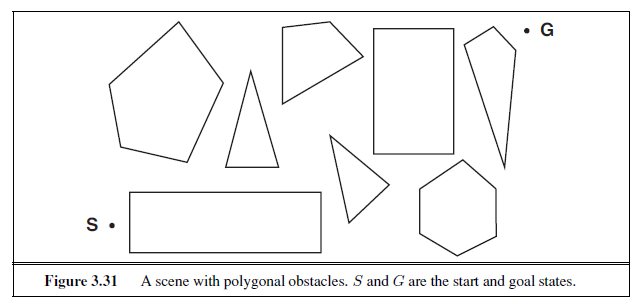

Robot navigation is a generalization of the route-finding problem described earlier.Rather than following a discrete set of routes, a robot can move in a continuous space with (in principle) an infinite set of possible actions and states. For a circular robot moving on a flat surface, the space is essentially two-dimensional. When the robot has arms and legs or wheels that must also be controlled, the search space becomes many-dimensional. Advanced techniques are required just to make the search space finite. We examine some of these methods in Chapter 25. In addition to the complexity of the problem, real robots must also deal with errors in their sensor readings and motor controls.

Automatic assembly sequencing of complex objects by a robot was first demonstrated by FREDDY (Michie, 1972). Progress since then has been slow but sure, to the point where the assembly of intricate objects such as electric motors is economically feasible. In assembly problems, the aim is to find an order in which to assemble the parts of some object. If the wrong order is chosen, there will be no way to add some part later in the sequence without undoing some of the work already done. Checking a step in the sequence for feasibility is a difficult geometrical search problem closely related to robot navigation. Thus, the generation of legal actions is the expensive part of assembly sequencing. Any practical algorithm must avoid exploring all but a tiny fraction of the state space. Another important assembly problem is protein design, in which the goal is to find a sequence of amino acids that will fold into a three-dimensional protein with the right properties to cure some disease.

SEARCHING FOR SOLUTIONS

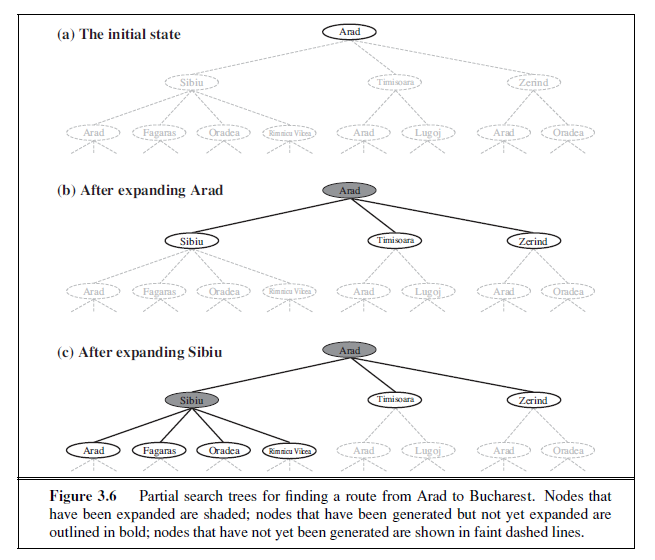

Having formulated some problems, we now need to solve them. A solution is an action sequence, so search algorithms work by considering various possible action sequences. The possible action sequences starting at the initial state form a search tree with the initial stateat the root; the branches are actions and the nodes correspond to states in the state space of the problem. Figure 3.6 shows the first few steps in growing the search tree for finding a route from Arad to Bucharest. The root node of the tree corresponds to the initial state, In(Arad). The first step is to test whether this is a goal state. (Clearly it is not, but it is important to check so that we can solve trick problems like “starting in Arad, get to Arad.”) Then we need to consider taking various actions. We do this by expanding the current state; that is,applying each legal action to the current state, thereby generating a new set of states. In this case, we add three branches from the parent node In(Arad) leading to three new child****nodes: In(Sibiu), In(Timisoara), and In(Zerind). Now we must choose which of these three possibilities to consider further.

This is the essence of search—following up one option now and putting the others aside for later, in case the first choice does not lead to a solution. Suppose we choose Sibiu first. We check to see whether it is a goal state (it is not) and then expand it to get In(Arad), In(Fagaras), In(Oradea), and In(RimnicuVilcea). We can then choose any of these four or go back and choose Timisoara or Zerind. Each of these six nodes is a leaf node, that is, a node with no children in the tree. The set of all leaf nodes available for expansion at any given point is called the frontier. (Many authors call it the open list, which is both geographically OPEN LIST less evocative and less accurate, because other data structures are better suited than a list.) In Figure 3.6, the frontier of each tree consists of those nodes with bold outlines.

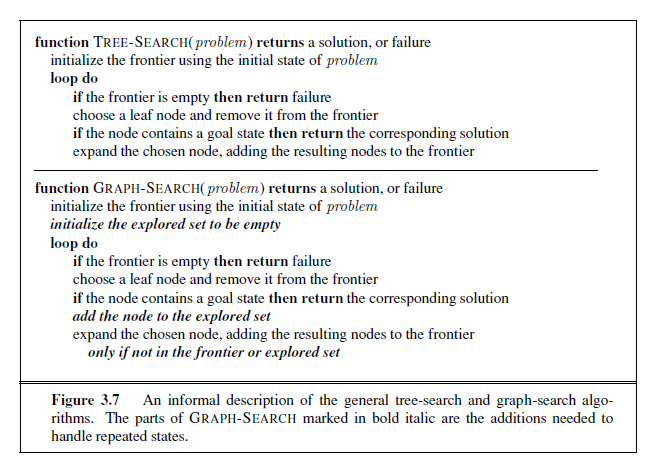

The process of expanding nodes on the frontier continues until either a solution is found or there are no more states to expand. The general TREE-SEARCH algorithm is shown informally in Figure 3.7. Search algorithms all share this basic structure; they vary primarily according to how they choose which state to expand next—the so-called search strategy.

The eagle-eyed reader will notice one peculiar thing about the search tree shown in Figure 3.6: it includes the path from Arad to Sibiu and back to Arad again! We say that In(Arad) is a repeated state in the search tree, generated in this case by a loopy path. Considering such loopy paths means that the complete search tree for Romania is infinite because there is no limit to how often one can traverse a loop. On the other hand, the state space—the map shown in Figure 3.2—has only 20 states. As we discuss in Section 3.4, loops can cause certain algorithms to fail, making otherwise solvable problems unsolvable. Fortunately, there is no need to consider loopy paths. We can rely on more than intuition for this: because path costs are additive and step costs are nonnegative, a loopy path to any given state is never better than the same path with the loop removed.

Loopy paths are a special case of the more general concept of redundant paths, which exist whenever there is more than one way to get from one state to another. Consider the paths Arad–Sibiu (140 km long) and Arad–Zerind–Oradea–Sibiu (297 km long). Obviously, the second path is redundant—it’s just a worse way to get to the same state. If you are concerned about reaching the goal, there’s never any reason to keep more than one path to any given state, because any goal state that is reachable by extending one path is also reachable by extending the other.

In some cases, it is possible to define the problem itself so as to eliminate redundant paths. For example, if we formulate the 8-queens problem (page 71) so that a queen can be placed in any column, then each state with n queens can be reached by n! different paths; but if we reformulate the problem so that each new queen is placed in the leftmost empty column, then each state can be reached only through one path.

In other cases, redundant paths are unavoidable. This includes all problems where the actions are reversible, such as route-finding problems and sliding-block puzzles. Routefinding on a rectangular grid (like the one used later for Figure 3.9) is a particularly important example in computer games. In such a grid, each state has four successors, so a search tree of depth d that includes repeated states has 4d leaves; but there are only about 2d2 distinct states within d steps of any given state. For d = 20, this means about a trillion nodes but only about 800 distinct states. Thus, following redundant paths can cause a tractable problem to become intractable. This is true even for algorithms that know how to avoid infinite loops.

As the saying goes, algorithms that forget their history are doomed to repeat it. The way to avoid exploring redundant paths is to remember where one has been. To do this, we augment the TREE-SEARCH algorithm with a data structure called the explored set (also known as the closed list), which remembers every expanded node. Newly generated nodes that match previously generated nodes—ones in the explored set or the frontier—can be discarded instead of being added to the frontier. The new algorithm, called GRAPH-SEARCH, is shown informally in Figure 3.7. The specific algorithms in this chapter draw on this general design.

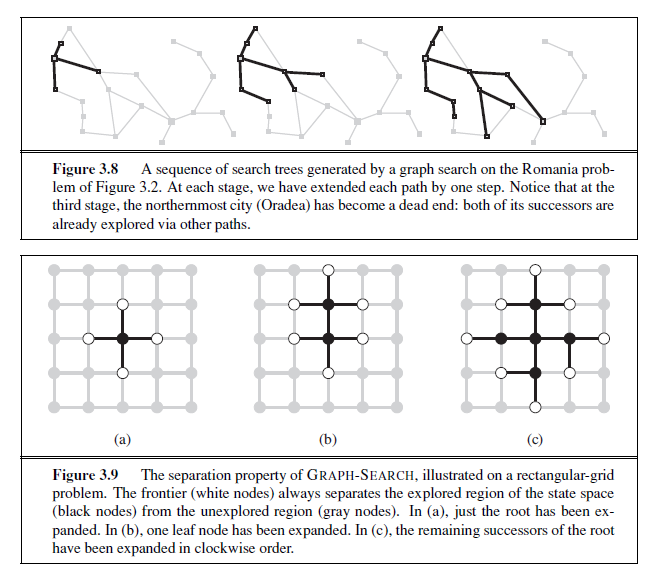

Clearly, the search tree constructed by the GRAPH-SEARCH algorithm contains at most one copy of each state, so we can think of it as growing a tree directly on the state-space graph, as shown in Figure 3.8. The algorithm has another nice property: the frontier separates the state-space graph into the explored region and the unexplored region, so that every path from

the initial state to an unexplored state has to pass through a state in the frontier. (If this seems completely obvious, try Exercise 3.13 now.) This property is illustrated in Figure 3.9. As every step moves a state from the frontier into the explored region while moving some states from the unexplored region into the frontier, we see that the algorithm is systematically examining the states in the state space, one by one, until it finds a solution.

Infrastructure for search algorithms

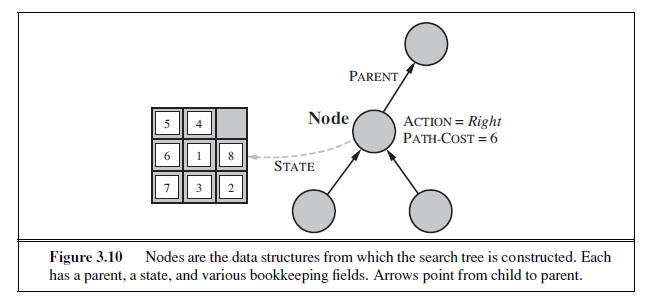

Search algorithms require a data structure to keep track of the search tree that is being constructed. For each node n of the tree, we have a structure that contains four components:

-

n.STATE: the state in the state space to which the node corresponds;

-

n.PARENT: the node in the search tree that generated this node;

-

n.ACTION: the action that was applied to the parent to generate the node;

-

n.PATH-COST: the cost, traditionally denoted by g(n), of the path from the initial state to the node, as indicated by the parent pointers.

Given the components for a parent node, it is easy to see how to compute the necessary components for a child node. The function CHILD-NODE takes a parent node and an action and returns the resulting child node:

function CHILD-NODE(problem ,parent ,action) returns a node

return a node with

STATE = problem .RESULT(parent .STATE,action ), PARENT = parent , ACTION = action ,

PATH-COST = parent .PATH-COST + problem .STEP-COST(parent .STATE,action )

The node data structure is depicted in Figure 3.10. Notice how the PARENT pointers string the nodes together into a tree structure. These pointers also allow the solution path to be extracted when a goal node is found; we use the SOLUTION function to return the sequence of actions obtained by following parent pointers back to the root.

Up to now, we have not been very careful to distinguish between nodes and states, but in writing detailed algorithms it’s important to make that distinction. A node is a bookkeeping data structure used to represent the search tree. A state corresponds to a configuration of the world. Thus, nodes are on particular paths, as defined by PARENT pointers, whereas states are not. Furthermore, two different nodes can contain the same world state if that state is generated via two different search paths.

Now that we have nodes, we need somewhere to put them. The frontier needs to be stored in such a way that the search algorithm can easily choose the next node to expand according to its preferred strategy. The appropriate data structure for this is a queue. TheQUEUE

operations on a queue are as follows:

-

EMPTY?(queue) returns true only if there are no more elements in the queue.

-

POP(queue) removes the first element of the queue and returns it.

-

INSERT(element , queue) inserts an element and returns the resulting queue.

Queues are characterized by the order in which they store the inserted nodes. Three common variants are the first-in, first-out or FIFO queue, which pops the oldest element of the queue; the last-in, first-out or LIFO queue (also known as a stack), which pops the newest element of the queue; and the priority queue, which pops the element of the queue with the highest priority according to some ordering function.

The explored set can be implemented with a hash table to allow efficient checking forepeated states. With a good implementation, insertion and lookup can be done in roughly constant time no matter how many states are stored. One must take care to implement the hash table with the right notion of equality between states. For example, in the traveling salesperson problem (page 74), the hash table needs to know that the set of visited cities {Bucharest,Urziceni,Vaslui} is the same as {Urziceni,Vaslui,Bucharest}. Sometimes this can be achieved most easily by insisting that the data structures for states be in some canonical form; that is, logically equivalent states should map to the same data structure. In the case of states described by sets, for example, a bit-vector representation or a sorted list without repetition would be canonical, whereas an unsorted list would not.

Measuring problem-solving performance

Before we get into the design of specific search algorithms, we need to consider the criteria that might be used to choose among them. We can evaluate an algorithm’s performance in four ways:

-

Completeness: Is the algorithm guaranteed to find a solution when there is one?

-

Optimality: Does the strategy find the optimal solution, as defined on page 68?

-

Time complexity: How long does it take to find a solution?

-

Space complexity: How much memory is needed to perform the search?

Time and space complexity are always considered with respect to some measure of the problem difficulty. In theoretical computer science, the typical measure is the size of the state space graph, |V | + |E|, where V is the set of vertices (nodes) of the graph and E is the set of edges (links). This is appropriate when the graph is an explicit data structure that is input to the search program. (The map of Romania is an example of this.) In AI, the graph is often represented implicitly by the initial state, actions, and transition model and is frequently infinite. For these reasons, complexity is expressed in terms of three quantities: b, the branching factor or maximum number of successors of any node; d, the depth of the shallowest goal node (i.e., the number of steps along the path from the root); and m, the maximum length of any path in the state space. Time is often measured in terms of the number of nodes generated during the search, and space in terms of the maximum number of nodes stored in memory. For the most part, we describe time and space complexity for search on a tree; for a graph, the answer depends on how “redundant” the paths in the state space are.

To assess the effectiveness of a search algorithm, we can consider just the search cost— which typically depends on the time complexity but can also include a term for memory usage—or we can use the total cost, which combines the search cost and the path cost of the solution found. For the problem of finding a route from Arad to Bucharest, the search cost is the amount of time taken by the search and the solution cost is the total length of the path in kilometers. Thus, to compute the total cost, we have to add milliseconds and kilometers. There is no “official exchange rate” between the two, but it might be reasonable in this case to convert kilometers into milliseconds by using an estimate of the car’s average speed (because time is what the agent cares about). This enables the agent to find an optimal tradeoff point at which further computation to find a shorter path becomes counterproductive. The more general problem of tradeoffs between different goods is taken up in Chapter 16.

UNINFORMED SEARCH STRATEGIES

This section covers several search strategies that come under the heading of uninformed search (also called blind search). The term means that the strategies have no additional information about states beyond that provided in the problem definition. All they can do is generate successors and distinguish a goal state from a non-goal state. All search strategies are distinguished by the order in which nodes are expanded. Strategies that know whether one non-goal state is “more promising” than another are called informed search or heuristic search strategies; they are covered in Section 3.5.

Breadth-first search

Breadth-first search is a simple strategy in which the root node is expanded first, then all the successors of the root node are expanded next, then their successors, and so on. In general, all the nodes are expanded at a given depth in the search tree before any nodes at the next level are expanded.

Breadth-first search is an instance of the general graph-search algorithm (Figure 3.7) in which the shallowest unexpanded node is chosen for expansion. This is achieved very simply by using a FIFO queue for the frontier. Thus, new nodes (which are always deeper than their parents) go to the back of the queue, and old nodes, which are shallower than the new nodes, get expanded first. There is one slight tweak on the general graph-search algorithm, which is that the goal test is applied to each node when it is generated rather than when it is selected for expansion. This decision is explained below, where we discuss time complexity. Note also that the algorithm, following the general template for graph search, discards any new path to a state already in the frontier or explored set; it is easy to see that any such path must be at least as deep as the one already found. Thus, breadth-first search always has the shallowest path to every node on the frontier

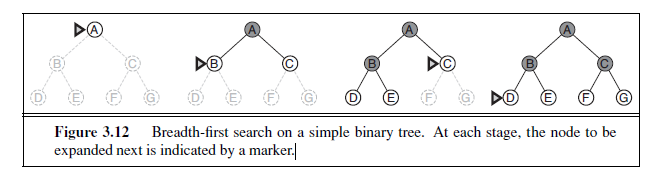

Pseudocode is given in Figure 3.11. Figure 3.12 shows the progress of the search on a simple binary tree.

How does breadth-first search rate according to the four criteria from the previous section? We can easily see that it is complete—if the shallowest goal node is at some finite depth d, breadth-first search will eventually find it after generating all shallower nodes (provided the branching factor b is finite). Note that as soon as a goal node is generated, we know it is the shallowest goal node because all shallower nodes must have been generated already and failed the goal test. Now, the shallowest goal node is not necessarily the optimal one;

function BREADTH-FIRST-SEARCH(problem

returns a solution, or failure

node← a node with STATE = problem .INITIAL-STATE, PATH-COST = 0

if problem .GOAL-TEST(node .STATE) then return SOLUTION(node)

frontier← a FIFO queue with node as the only element

explored← an empty set

loop do

if EMPTY?( frontier ) then return failure node← POP( frontier ) /* chooses the shallowest node in frontier */

add node .STATE to explored

for each action in problem .ACTIONS(node.STATE) do

child←CHILD-NODE(problem ,node ,action)

if child .STATE is not in explored or frontier then

if problem .GOAL-TEST(child .STATE) then return SOLUTION(child )

frontier← INSERT(child , frontier )

Figure 3.11 Breadth-first search on a graph.

technically, breadth-first search is optimal if the path cost is a nondecreasing function of the depth of the node. The most common such scenario is that all actions have the same cost.

So far, the news about breadth-first search has been good. The news about time and space is not so good. Imagine searching a uniform tree where every state has b successors. The root of the search tree generates b nodes at the first level, each of which generates b more nodes, for a total of b

2 at the second level. Each of these generates b more nodes, yielding b 3

nodes at the third level, and so on. Now suppose that the solution is at depth d. In the worst case, it is the last node generated at that level. Then the total number of nodes generated is

b + b^2^ + b^3^ + · · ·+ bd = O(bd ) .

(If the algorithm were to apply the goal test to nodes when selected for expansion, rather than when generated, the whole layer of nodes at depth d would be expanded before the goal was detected and the time complexity would be O(b^d+1^).)

As for space complexity: for any kind of graph search, which stores every expanded node in the explored set, the space complexity is always within a factor of b of the time complexity. For breadth-first graph search in particular, every node generated remains in memory. There will be O(b^d−1^) nodes in the explored set and O(bd) nodes in the frontier,

so the space complexity is O(bd), i.e., it is dominated by the size of the frontier. Switching to a tree search would not save much space, and in a state space with many redundant paths, switching could cost a great deal of time.

An exponential complexity bound such as O(bd) is scary. Figure 3.13 shows why. It lists, for various values of the solution depth d, the time and memory required for a breadthfirst search with branching factor b = 10. The table assumes that 1 million nodes can be generated per second and that a node requires 1000 bytes of storage. Many search problems fit roughly within these assumptions (give or take a factor of 100) when run on a modern personal computer.

| Depth | Nodes | Time | Memory |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 110 | .11 milliseconds | 107 kilobytes |

| 4 | 11,110 | 11 milliseconds | 10.6 megabytes |

| 6 | 10^6^ | 1.1 seconds | 1 gigabyte |

| 8 | 10^8^ | 2 minutes | 103 gigabytes |

| 10 | 10^10^ | 3 hours | 10 terabytes |

| 12 | 10^12^ | 13 days | 1 petabyte |

| 14 | 10^14^ | 3.5 years | 99 petabytes |

| 16 | 10^16^ | 350 years | 10 exabytes |

Figure 3.13 Time and memory requirements for breadth-first search. The numbers shown assume branching factor b = 10; 1 million nodes/second; 1000 bytes/node.

Two lessons can be learned from Figure 3.13. First, the memory requirements are a bigger problem for breadth-first search than is the execution time. One might wait 13 days for the solution to an important problem with search depth 12, but no personal computer has the petabyte of memory it would take. Fortunately, other strategies require less memory.

The second lesson is that time is still a major factor. If your problem has a solution at depth 16, then (given our assumptions) it will take about 350 years for breadth-first search (or indeed any uninformed search) to find it. In general, exponential-complexity search problems cannot be solved by uninformed methods for any but the smallest instances.

Uniform-cost search

When all step costs are equal, breadth-first search is optimal because it always expands the shallowest unexpanded node. By a simple extension, we can find an algorithm that is optimal with any step-cost function. Instead of expanding the shallowest node, uniform-cost search expands the node n with the lowest path cost g(n). This is done by storing the frontier as a priority queue ordered by g. The algorithm is shown in Figure 3.14.

In addition to the ordering of the queue by path cost, there are two other significant differences from breadth-first search. The first is that the goal test is applied to a node when it is selected for expansion (as in the generic graph-search algorithm shown in Figure 3.7) rather than when it is first generated. The reason is that the first goal node that is generated

function UNIFORM-COST-SEARCH(problem) returns a solution, or failure

node← a node with STATE = problem .INITIAL-STATE, PATH-COST = 0

frontier← a priority queue ordered by PATH-COST, with node as the only element

explored← an empty set

loop do

if EMPTY?( frontier ) then return failure

node← POP( frontier ) /* chooses the lowest-cost node in frontier */

if problem .GOAL-TEST(node.STATE) then return SOLUTION(node)

add node .STATE to explored

for each action in problem .ACTIONS(node.STATE) do \

child←CHILD-NODE(problem ,node ,action)

if child .STATE is not in explored or frontier then

frontier← INSERT(child , frontier )

else if child .STATE is in frontier with higher PATH-COST then

replace that frontier node with child

Figure 3.14 Uniform-cost search on a graph. The algorithm is identical to the general graph search algorithm in Figure 3.7, except for the use of a priority queue and the addition of an extra check in case a shorter path to a frontier state is discovered. The data structure for frontier needs to support efficient membership testing, so it should combine the capabilities of a priority queue and a hash table.

may be on a suboptimal path. The second difference is that a test is added in case a better path is found to a node currently on the frontier.

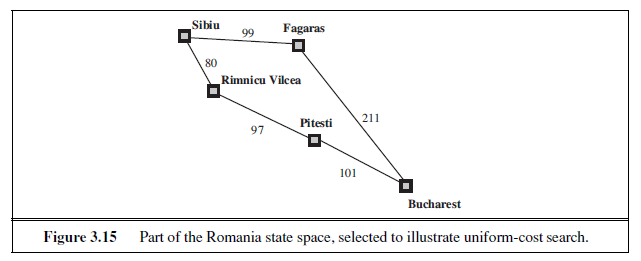

Both of these modifications come into play in the example shown in Figure 3.15, where the problem is to get from Sibiu to Bucharest. The successors of Sibiu are Rimnicu Vilcea and Fagaras, with costs 80 and 99, respectively. The least-cost node, Rimnicu Vilcea, is expanded next, adding Pitesti with cost 80 + 97= 177. The least-cost node is now Fagaras, so it is expanded, adding Bucharest with cost 99 + 211= 310. Now a goal node has been generated, but uniform-cost search keeps going, choosing Pitesti for expansion and adding a second path to Bucharest with cost 80+97+101= 278. Now the algorithm checks to see if this new path is better than the old one; it is, so the old one is discarded. Bucharest, now with g-cost 278, is selected for expansion and the solution is returned.

It is easy to see that uniform-cost search is optimal in general. First, we observe that whenever uniform-cost search selects a node n for expansion, the optimal path to that node has been found. (Were this not the case, there would have to be another frontier node n′ on the optimal path from the start node to n, by the graph separation property of Figure 3.9; by definition, n′ would have lower g-cost than n and would have been selected first.) Then, because step costs are nonnegative, paths never get shorter as nodes are added. These two facts together imply that uniform-cost search expands nodes in order of their optimal path cost. Hence, the first goal node selected for expansion must be the optimal solution.

Uniform-cost search does not care about the number of steps a path has, but only about their total cost. Therefore, it will get stuck in an infinite loop if there is a path with an infinite sequence of zero-cost actions—for example, a sequence of NoOp actions.6 Completeness is guaranteed provided the cost of every step exceeds some small positive constant ε.

Uniform-cost search is guided by path costs rather than depths, so its complexity is not easily characterized in terms of b and d. Instead, let C∗ be the cost of the optimal solution,7and assume that every action costs at least ε. Then the algorithm’s worst-case time and space complexity is O(b^1+[C∗ε]^), which can be much greater than bd. This is because uniformcost search can explore large trees of small steps before exploring paths involving large and perhaps useful steps. When all step costs are equal, b^1+[C∗ε]^ is just b^d+1^. When all step costs are the same, uniform-cost search is similar to breadth-first search, except that the latter stops as soon as it generates a goal, whereas uniform-cost search examines all the nodes at the goal’s depth to see if one has a lower cost; thus uniform-cost search does strictly more work by expanding nodes at depth d unnecessarily.

Depth-first search

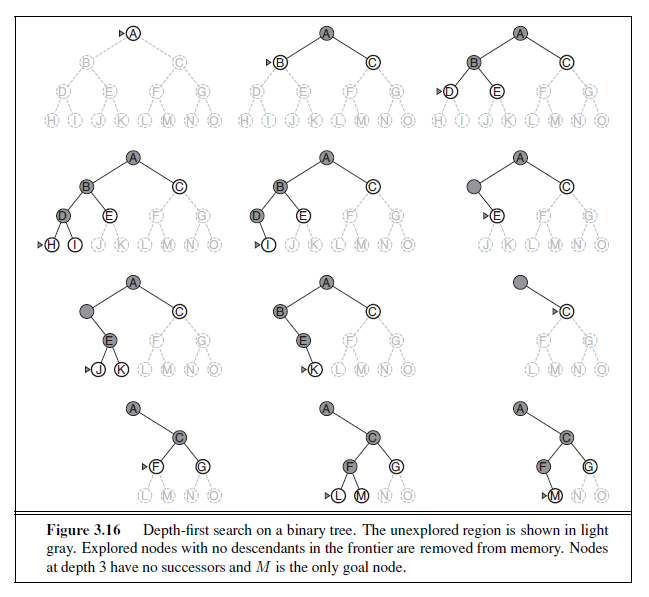

Depth-first search always expands the deepest node in the current frontier of the search tree. The progress of the search is illustrated in Figure 3.16. The search proceeds immediately to the deepest level of the search tree, where the nodes have no successors. As those nodes are expanded, they are dropped from the frontier, so then the search “backs up” to the next deepest node that still has unexplored successors.

The depth-first search algorithm is an instance of the graph-search algorithm in Figure 3.7; whereas breadth-first-search uses a FIFO queue, depth-first search uses a LIFO queue. A LIFO queue means that the most recently generated node is chosen for expansion. This must be the deepest unexpanded node because it is one deeper than its parent—which, in turn, was the deepest unexpanded node when it was selected.

As an alternative to the GRAPH-SEARCH-style implementation, it is common to implement depth-first search with a recursive function that calls itself on each of its children in turn. (A recursive depth-first algorithm incorporating a depth limit is shown in Figure 3.17.)

6 NoOp, or “no operation,” is the name of an assembly language instruction that does nothing. 7 Here, and throughout the book, the “star” in C∗ means an optimal value for C.

The properties of depth-first search depend strongly on whether the graph-search or tree-search version is used. The graph-search version, which avoids repeated states and redundant paths, is complete in finite state spaces because it will eventually expand every node. The tree-search version, on the other hand, is not complete—for example, in Figure 3.6 the algorithm will follow the Arad–Sibiu–Arad–Sibiu loop forever. Depth-first tree search can be modified at no extra memory cost so that it checks new states against those on the path from the root to the current node; this avoids infinite loops in finite state spaces but does not avoid the proliferation of redundant paths. In infinite state spaces, both versions fail if an infinite non-goal path is encountered. For example, in Knuth’s 4 problem, depth-first search would keep applying the factorial operator forever.

For similar reasons, both versions are nonoptimal. For example, in Figure 3.16, depthfirst search will explore the entire left subtree even if node C is a goal node. If node J were also a goal node, then depth-first search would return it as a solution instead of C , which would be a better solution; hence, depth-first search is not optimal.

The time complexity of depth-first graph search is bounded by the size of the state space (which may be infinite, of course). A depth-first tree search, on the other hand, may generate all of the O(bm) nodes in the search tree, where m is the maximum depth of any node; this can be much greater than the size of the state space. Note that m itself can be much larger than d (the depth of the shallowest solution) and is infinite if the tree is unbounded.

So far, depth-first search seems to have no clear advantage over breadth-first search, so why do we include it? The reason is the space complexity. For a graph search, there is no advantage, but a depth-first tree search needs to store only a single path from the root to a leaf node, along with the remaining unexpanded sibling nodes for each node on the path. Once a node has been expanded, it can be removed from memory as soon as all its descendants have been fully explored. (See Figure 3.16.) For a state space with branching factor b and maximum depth m, depth-first search requires storage of only O(bm) nodes. Using the same assumptions as for Figure 3.13 and assuming that nodes at the same depth as the goal node have no successors, we find that depth-first search would require 156 kilobytes instead of 10 exabytes at depth d = 16, a factor of 7 trillion times less space. This has led to the adoption of depth-first tree search as the basic workhorse of many areas of AI, including constraint satisfaction (Chapter 6), propositional satisfiability (Chapter 7), and logic programming (Chapter 9). For the remainder of this section, we focus primarily on the treesearch version of depth-first search.

A variant of depth-first search called backtracking search uses still less memory. (See Chapter 6 for more details.) In backtracking, only one successor is generated at a time rather than all successors; each partially expanded node remembers which successor to generate next. In this way, only O(m) memory is needed rather than O(bm). Backtracking search facilitates yet another memory-saving (and time-saving) trick: the idea of generating a successor by modifying the current state description directly rather than copying it first. This reduces the memory requirements to just one state description and O(m) actions. For this to work, we must be able to undo each modification when we go back to generate the next successor. For problems with large state descriptions, such as robotic assembly, these techniques are critical to success.

Depth-limited search

The embarrassing failure of depth-first search in infinite state spaces can be alleviated by supplying depth-first search with a predetermined depth limit λ. That is, nodes at depth λ are treated as if they have no successors. This approach is called depth-limited search. The depth limit solves the infinite-path problem. Unfortunately, it also introduces an additional source of incompleteness if we choose λ < d, that is, the shallowest goal is beyond the depth limit. (This is likely when d is unknown.) Depth-limited search will also be nonoptimal if we choose λ > d. Its time complexity is O(bλ) and its space complexity is O(bλ). Depth-first search can be viewed as a special case of depth-limited search with λ=∞.

Sometimes, depth limits can be based on knowledge of the problem. For example, on the map of Romania there are 20 cities. Therefore, we know that if there is a solution, it must be of length 19 at the longest, so λ = 19 is a possible choice. But in fact if we studied the

function DEPTH-LIMITED-SEARCH(problem , limit ) returns a solution, or failure cutoff return \ RECURSIVE-DLS(MAKE-NODE(problem .INITIAL-STATE),problem , limit )

function RECURSIVE-DLS(node,problem , limit ) returns a solution, or failure/cutoff

if problem .GOAL-TEST(node .STATE) then return SOLUTION(node) \

else if limit = 0 then return cutoff

else \

cutoff occurred?← false

for each action in problem .ACTIONS(node.STATE) do

child←CHILD-NODE(problem ,node ,action

result←RECURSIVE-DLS(child ,problem , limit − 1

if result = cutoff then cutoff occurred?← true

else if result ≠ failure then return result

if cutoff occurred? then return cutoff else return failure

Figure 3.17 A recursive implementation of depth-limited tree search.

map carefully, we would discover that any city can be reached from any other city in at most 9 steps. This number, known as the diameter of the state space, gives us a better depth limit,which leads to a more efficient depth-limited search. For most problems, however, we will not know a good depth limit until we have solved the problem.

Depth-limited search can be implemented as a simple modification to the general treeor graph-search algorithm. Alternatively, it can be implemented as a simple recursive algorithm as shown in Figure 3.17. Notice that depth-limited search can terminate with two kinds of failure: the standard failure value indicates no solution; the cutoff value indicates no solution within the depth limit.

Iterative deepening depth-first search

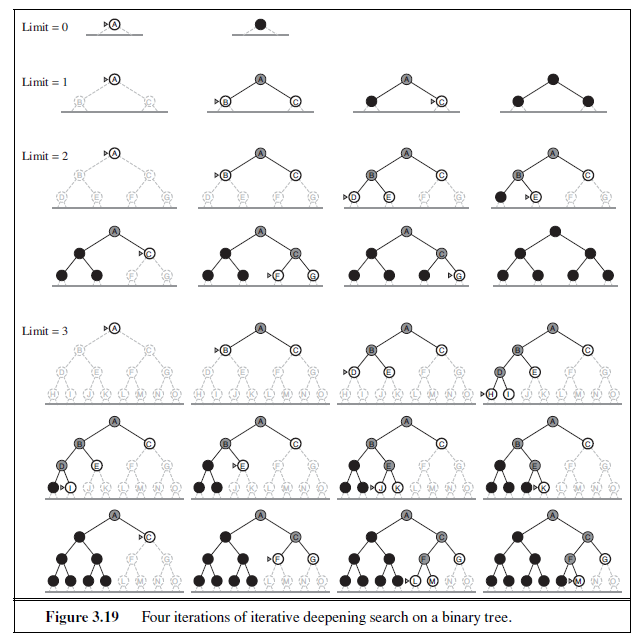

Iterative deepening search (or iterative deepening depth-first search) is a general strategy often used in combination with depth-first tree search, that finds the best depth limit. It does this by gradually increasing the limit—first 0, then 1, then 2, and so on—until a goal is found. This will occur when the depth limit reaches d, the depth of the shallowest goal node. The algorithm is shown in Figure 3.18. Iterative deepening combines the benefits of depth-first and breadth-first search. Like depth-first search, its memory requirements are modest: O(bd) to be precise. Like breadth-first search, it is complete when the branching factor is finite and optimal when the path cost is a nondecreasing function of the depth of the node. Figure 3.19 shows four iterations of ITERATIVE-DEEPENING-SEARCH on a binary search tree, where the solution is found on the fourth iteration.

Iterative deepening search may seem wasteful because states are generated multiple times. It turns out this is not too costly. The reason is that in a search tree with the same (or nearly the same) branching factor at each level, most of the nodes are in the bottom level, so it does not matter much that the upper levels are generated multiple times. In an iterative deepening search, the nodes on the bottom level (depth d) are generated once, those on the

function ITERATIVE-DEEPENING-SEARCH(problem) returns a solution, or failure

for depth = 0 to ∞ do

result←DEPTH-LIMITED-SEARCH(problem ,depth)

if result ≠ cutoff then return result

Figure 3.18 The iterative deepening search algorithm, which repeatedly applies depthlimited search with increasing limits. It terminates when a solution is found or if the depthlimited search returns failure , meaning that no solution exists.

next-to-bottom level are generated twice, and so on, up to the children of the root, which are generated d times. So the total number of nodes generated in the worst case is

N(IDS) = (d)b + (d− 1)b^2^ + · · ·+ (1)b^d^ ,

which gives a time complexity of O(bd)—asymptotically the same as breadth-first search. There is some extra cost for generating the upper levels multiple times, but it is not large. For example, if b = 10 and d = 5, the numbers are

N(IDS) = 50 + 400 + 3, 000 + 20, 000 + 100, 000 = 123, 450

N(BFS) = 10 + 100 + 1, 000 + 10, 000 + 100, 000 = 111, 110 .

If you are really concerned about repeating the repetition, you can use a hybrid approach that runs breadth-first search until almost all the available memory is consumed, and then runs iterative deepening from all the nodes in the frontier. In general, iterative deepening is the preferred uninformed search method when the search space is large and the depth of the solution is not known.

Iterative deepening search is analogous to breadth-first search in that it explores a complete layer of new nodes at each iteration before going on to the next layer. It would seem worthwhile to develop an iterative analog to uniform-cost search, inheriting the latter algorithm’s optimality guarantees while avoiding its memory requirements. The idea is to use increasing path-cost limits instead of increasing depth limits. The resulting algorithm, called iterative lengthening search, is explored in Exercise 3.17. It turns out, unfortunately, that iterative lengthening incurs substantial overhead compared to uniform-cost search.

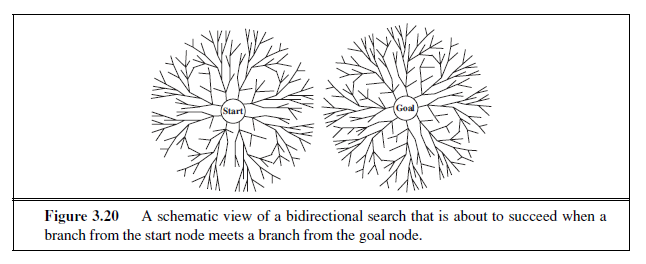

Bidirectional search

The idea behind bidirectional search is to run two simultaneous searches—one forward from the initial state and the other backward from the goal—hoping that the two searches meet in the middle (Figure 3.20). The motivation is that b^d/2^+ b^d/2^is much less than b^d^, or in the figure, the area of the two small circles is less than the area of one big circle centered on the start and reaching to the goal.

Bidirectional search is implemented by replacing the goal test with a check to see whether the frontiers of the two searches intersect; if they do, a solution has been found. (It is important to realize that the first such solution found may not be optimal, even if the two searches are both breadth-first; some additional search is required to make sure there isn’t another short-cut across the gap.) The check can be done when each node is generated or selected for expansion and, with a hash table, will take constant time. For example, if a problem has solution depth d= 6, and each direction runs breadth-first search one node at a time, then in the worst case the two searches meet when they have generated all of the nodes at depth 3. For b= 10, this means a total of 2,220 node generations, compared with 1,111,110 for a standard breadth-first search. Thus, the time complexity of bidirectional search using breadth-first searches in both directions is O(bd/2). The space complexity is also O(bd/2). We can reduce this by roughly half if one of the two searches is done by iterative deepening, but at least one of the frontiers must be kept in memory so that the intersection check can be done. This space requirement is the most significant weakness of bidirectional search.

The reduction in time complexity makes bidirectional search attractive, but how do we search backward? This is not as easy as it sounds. Let the predecessors of a state x be all those states that have x as a successor. Bidirectional search requires a method for computing predecessors. When all the actions in the state space are reversible, the predecessors of x are just its successors. Other cases may require substantial ingenuity.

Consider the question of what we mean by “the goal” in searching “backward from the goal.” For the 8-puzzle and for finding a route in Romania, there is just one goal state, so the backward search is very much like the forward search. If there are several explicitly listed goal states—for example, the two dirt-free goal states in Figure 3.3—then we can construct a new dummy goal state whose immediate predecessors are all the actual goal states. But if the goal is an abstract description, such as the goal that “no queen attacks another queen” in the n-queens problem, then bidirectional search is difficult to use.

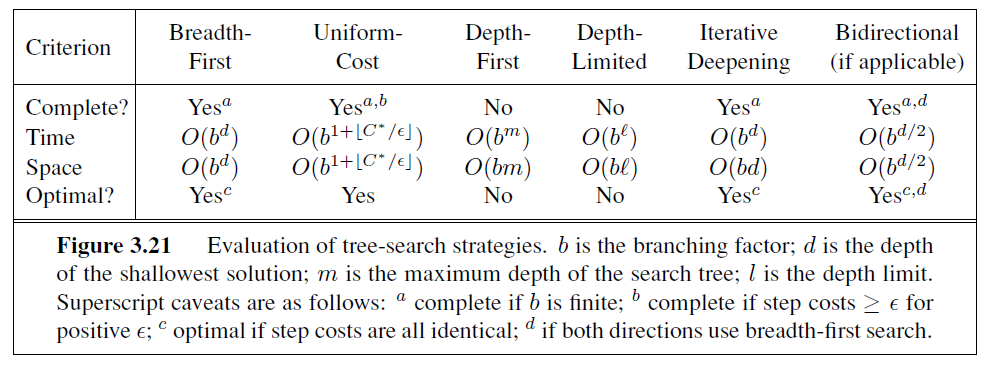

Comparing uninformed search strategies

Figure 3.21 compares search strategies in terms of the four evaluation criteria set forth in Section 3.3.2. This comparison is for tree-search versions. For graph searches, the main differences are that depth-first search is complete for finite state spaces and that the space and time complexities are bounded by the size of the state space.

INFORMED (HEURISTIC) SEARCH STRATEGIES

This section shows how an informed search strategy—one that uses problem-specific knowledge beyond the definition of the problem itself—can find solutions more efficiently than can an uninformed strategy.

The general approach we consider is called best-first search. Best-first search is an instance of the general TREE-SEARCH or GRAPH-SEARCH algorithm in which a node is selected for expansion based on an evaluation function, f(n). The evaluation function is construed as a cost estimate, so the node with the lowest evaluation is expanded first. The implementation of best-first graph search is identical to that for uniform-cost search (Figure 3.14), except for the use of f instead of g to order the priority queue.

The choice of f determines the search strategy. (For example, as Exercise 3.21 shows, best-first tree search includes depth-first search as a special case.) Most best-first algorithms include as a component of f a heuristic function, denoted h(n): h(n) = estimated cost of the cheapest path from the state at node n to a goal state.(Notice that h(n) takes a node as input, but, unlike g(n), it depends only on the state at that node.) For example, in Romania, one might estimate the cost of the cheapest path from Arad to Bucharest via the straight-line distance from Arad to Bucharest.

Heuristic functions are the most common form in which additional knowledge of the problem is imparted to the search algorithm. We study heuristics in more depth in Section 3.6. For now, we consider them to be arbitrary, nonnegative, problem-specific functions, with one constraint: if n is a goal node, then h(n)= 0. The remainder of this section covers two ways to use heuristic information to guide search.

Greedy best-first search

Greedy best-first search8 tries to expand the node that is closest to the goal, on the grounds that this is likely to lead to a solution quickly. Thus, it evaluates nodes by using just the heuristic function; that is, f(n) = h(n).

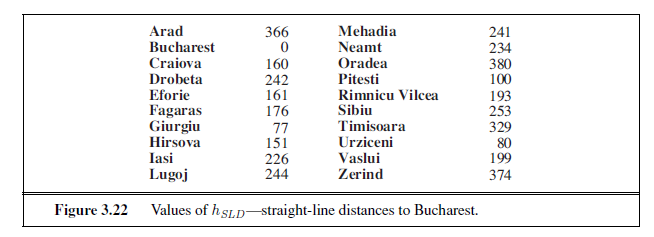

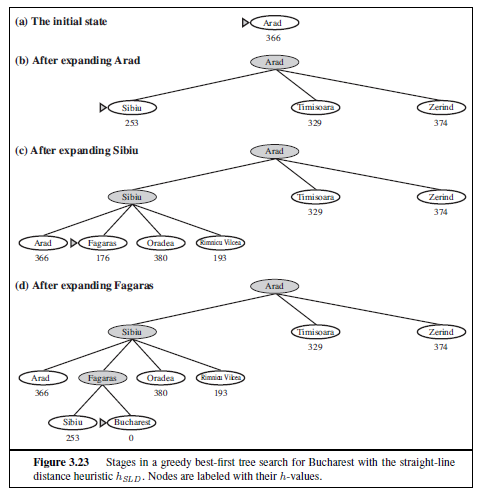

Let us see how this works for route-finding problems in Romania; we use the straightline distance heuristic, which we will call hSLD . If the goal is Bucharest, we need to know the straight-line distances to Bucharest, which are shown in Figure 3.22. For example, hSLD(In(Arad))= 366. Notice that the values of hSLD cannot be computed from the problem description itself. Moreover, it takes a certain amount of experience to know that hSLD is correlated with actual road distances and is, therefore, a useful heuristic.

Figure 3.23 shows the progress of a greedy best-first search using hSLD to find a path from Arad to Bucharest. The first node to be expanded from Arad will be Sibiu because it is closer to Bucharest than either Zerind or Timisoara. The next node to be expanded will be Fagaras because it is closest. Fagaras in turn generates Bucharest, which is the goal. For this particular problem, greedy best-first search using hSLD finds a solution without ever

8 Our first edition called this greedy search; other authors have called it best-first search. Our more general usage of the latter term follows Pearl (1984).

expanding a node that is not on the solution path; hence, its search cost is minimal. It is not optimal, however: the path via Sibiu and Fagaras to Bucharest is 32 kilometers longer than the path through Rimnicu Vilcea and Pitesti. This shows why the algorithm is called “greedy”—at each step it tries to get as close to the goal as it can.

Greedy best-first tree search is also incomplete even in a finite state space, much like depth-first search. Consider the problem of getting from Iasi to Fagaras. The heuristic suggests that Neamt be expanded first because it is closest to Fagaras, but it is a dead end. The solution is to go first to Vaslui—a step that is actually farther from the goal according to the heuristic—and then to continue to Urziceni, Bucharest, and Fagaras. The algorithm will never find this solution, however, because expanding Neamt puts Iasi back into the frontier, Iasi is closer to Fagaras than Vaslui is, and so Iasi will be expanded again, leading to an infinite loop. (The graph search version is complete in finite spaces, but not in infinite ones.) The worst-case time and space complexity for the tree version is O(bm), where m is the maximum depth of the search space. With a good heuristic function, however, the complexity can be reduced substantially. The amount of the reduction depends on the particular problem and on the quality of the heuristic.

A* search: Minimizing the total estimated solution cost

The most widely known form of best-first search is called A∗ search (pronounced “A-starA search”). It evaluates nodes by combining g(n), the cost to reach the node, and h(n), the cost to get from the node to the goal:

f(n) = g(n) + h(n) .

Since g(n) gives the path cost from the start node to node n, and h(n) is the estimated cost of the cheapest path from n to the goal, we have

f(n) = estimated cost of the cheapest solution through n .

Thus, if we are trying to find the cheapest solution, a reasonable thing to try first is the node with the lowest value of g(n) + h(n). It turns out that this strategy is more than just reasonable: provided that the heuristic function h(n) satisfies certain conditions, A∗ search is both complete and optimal. The algorithm is identical to UNIFORM-COST-SEARCH except that A∗ uses g + h instead of g.

Conditions for optimality: Admissibility and consistency

The first condition we require for optimality is that h(n) be an admissible heuristic. An admissible heuristic is one that never overestimates the cost to reach the goal. Because g(n) is the actual cost to reach n along the current path, and f(n)= g(n) + h(n), we have as an immediate consequence that f(n) never overestimates the true cost of a solution along the current path through n.

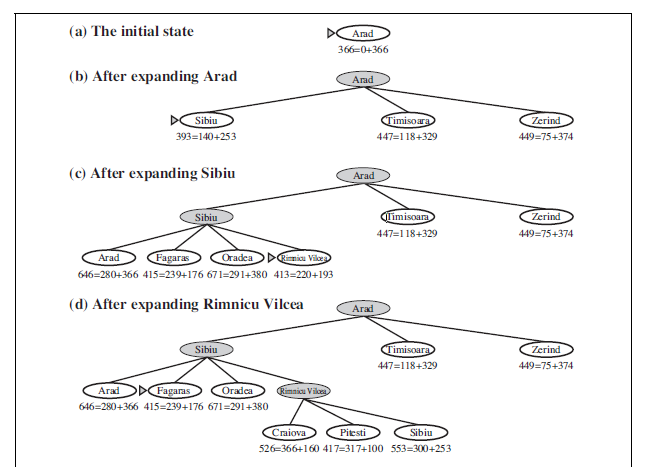

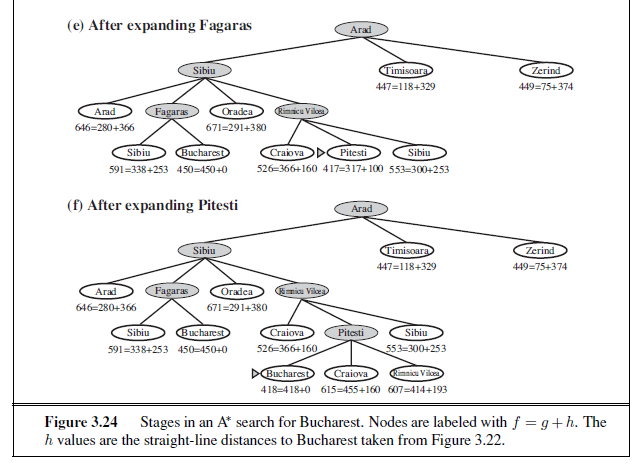

Admissible heuristics are by nature optimistic because they think the cost of solving the problem is less than it actually is. An obvious example of an admissible heuristic is the straight-line distance hSLD that we used in getting to Bucharest. Straight-line distance is admissible because the shortest path between any two points is a straight line, so the straight line cannot be an overestimate. In Figure 3.24, we show the progress of an A∗ tree search for Bucharest. The values of g are computed from the step costs in Figure 3.2, and the values of hSLD are given in Figure 3.22. Notice in particular that Bucharest first appears on the frontier at step (e), but it is not selected for expansion because its f -cost (450) is higher than that of Pitesti (417). Another way to say this is that there might be a solution through Pitesti whose cost is as low as 417, so the algorithm will not settle for a solution that costs 450.

A second, slightly stronger condition called consistency (or sometimes monotonicity)is required only for applications of A∗ to graph search.9 A heuristic h(n) is consistent if, for every node n and every successor n′ of n generated by any action a, the estimated cost of reaching the goal from n is no greater than the step cost of getting to n′ plus the estimated cost of reaching the goal from n′:

h(n) ≤ c(n, a, n′) + h(n′) .

This is a form of the general triangle inequality, which stipulates that each side of a triangle cannot be longer than the sum of the other two sides. Here, the triangle is formed by n, n′,and the goal G~n~ closest to n. For an admissible heuristic, the inequality makes perfect sense: if there were a route from n toG~n~via n′ that was cheaper than h(n), that would violate the property that h(n) is a lower bound on the cost to reach G~n~.

It is fairly easy to show (Exercise 3.29) that every consistent heuristic is also admissible. Consistency is therefore a stricter requirement than admissibility, but one has to work quite hard to concoct heuristics that are admissible but not consistent. All the admissible heuristics we discuss in this chapter are also consistent. Consider, for example, hSLD . We know that the general triangle inequality is satisfied when each side is measured by the straight-line distance and that the straight-line distance between n and n′ is no greater than c(n, a, n′).Hence, hSLD is a consistent heuristic.

Optimality of A

As we mentioned earlier, A∗ has the following properties: the tree-search version of A ∗ is optimal if h(n) is admissible, while the graph-search version is optimal if h(n) is consistent. We show the second of these two claims since it is more useful. The argument essentially mirrors the argument for the optimality of uniform-cost search, with g replaced by f—just as in the A∗ algorithm itself.

The first step is to establish the following: if h(n) is consistent, then the values of f(n) along any path are nondecreasing. The proof follows directly from the definition of consistency. Suppose n′ is a successor of n; then g(n′)= g(n) + c(n, a, n′) for some action a, and we have

f(n′) = g(n′) + h(n′) = g(n) + c(n, a, n′) + h(n′) ≥ g(n) + h(n) = f(n) .

The next step is to prove that whenever A ∗ selects a node n for expansion, the optimal path to that node has been found. Were this not the case, there would have to be another frontier node n′ on the optimal path from the start node to n, by the graph separation property of

9 With an admissible but inconsistent heuristic, A∗ requires some extra bookkeeping to ensure optimality.

Figure 3.9; because f is nondecreasing along any path, n′ would have lower f -cost than n and would have been selected first.

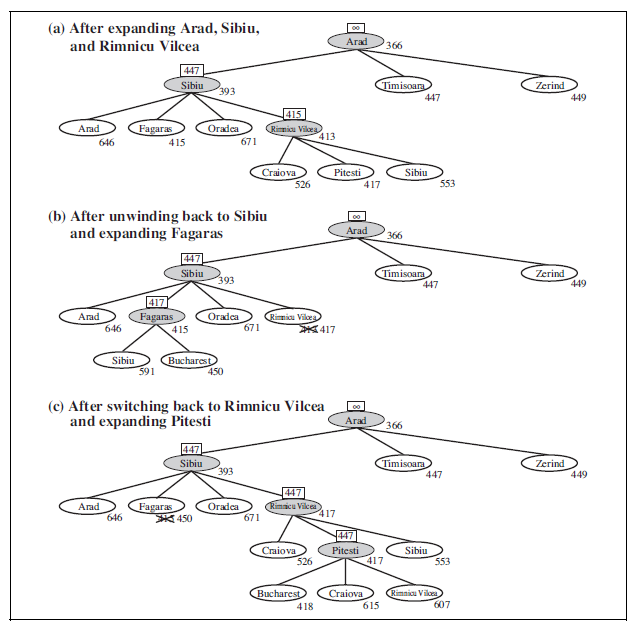

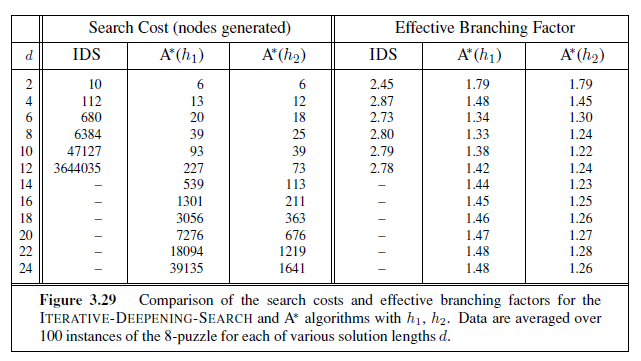

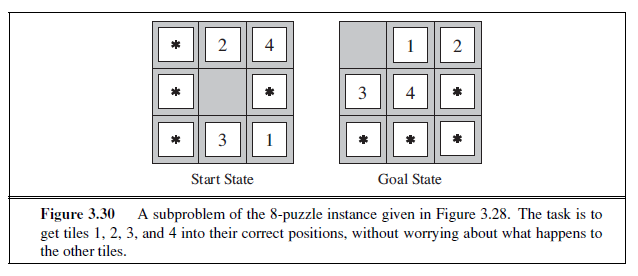

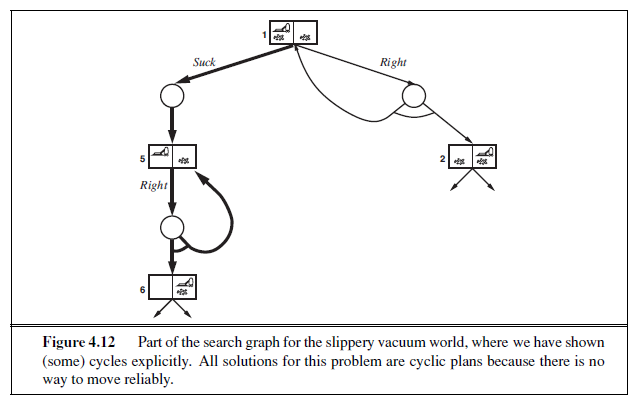

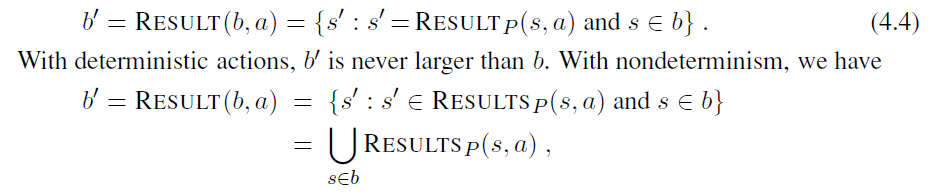

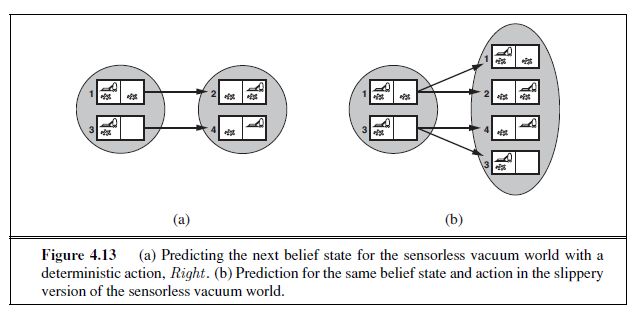

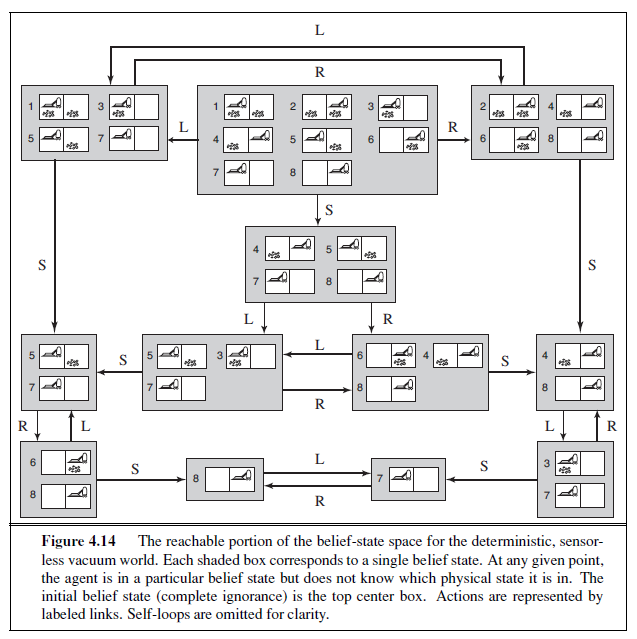

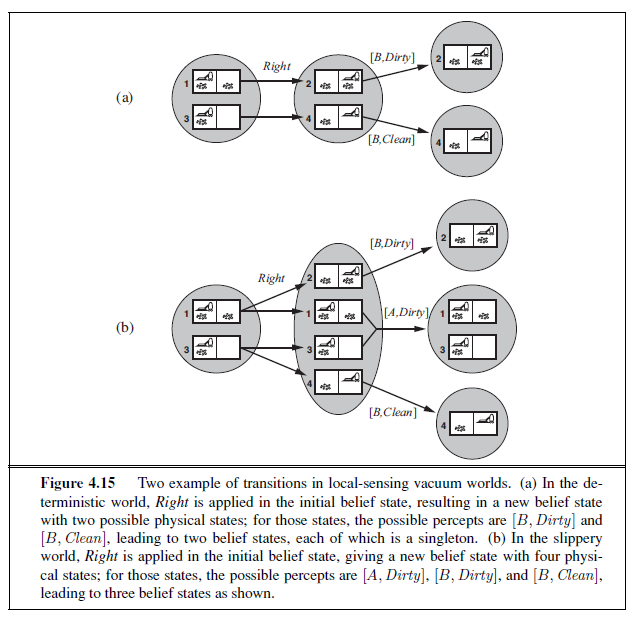

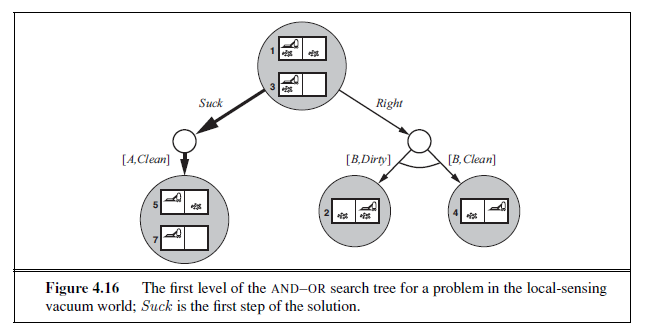

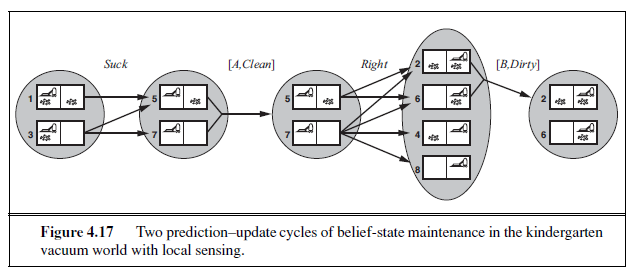

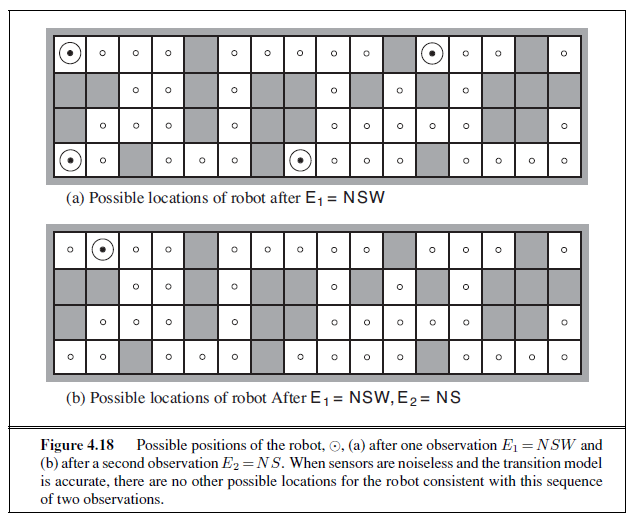

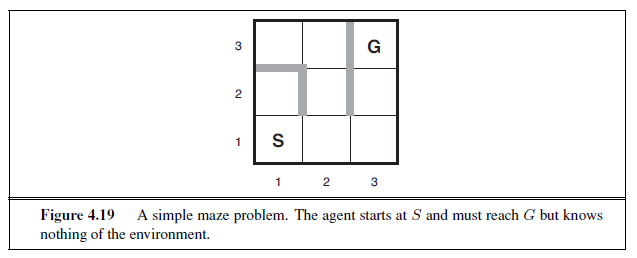

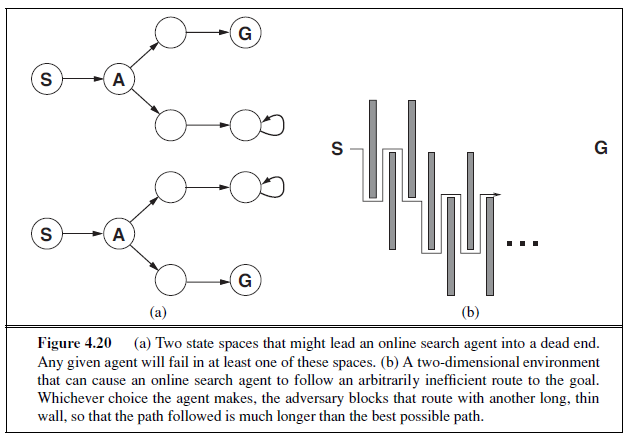

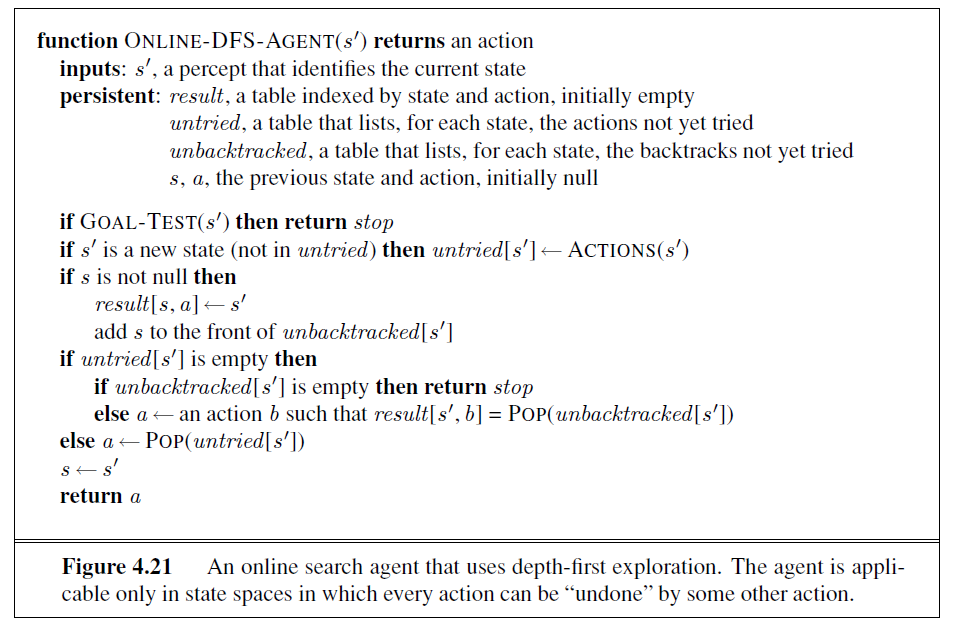

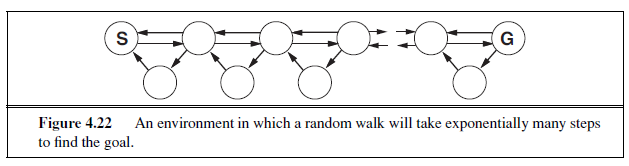

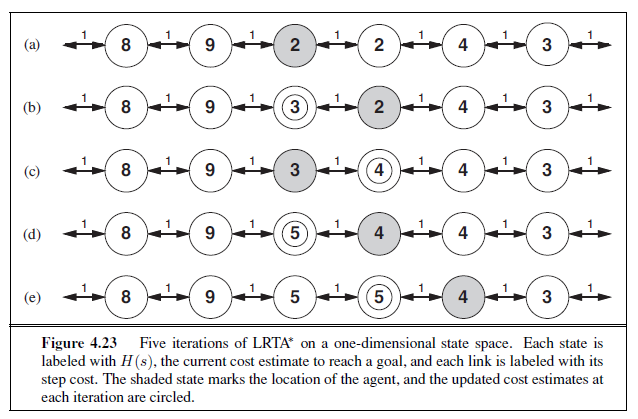

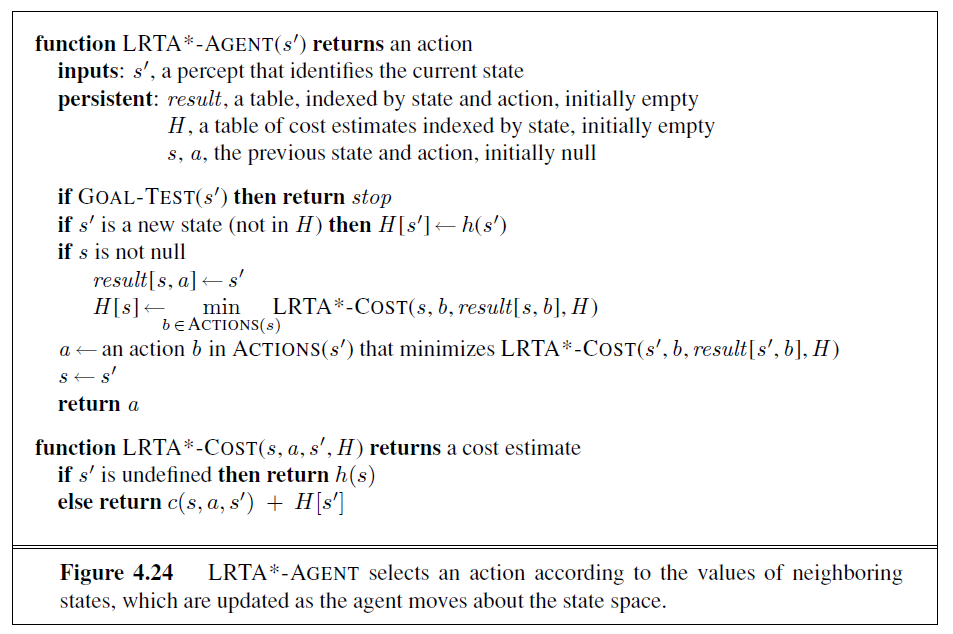

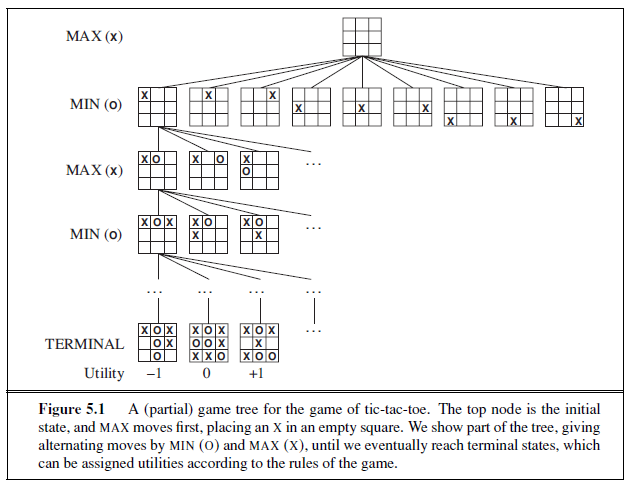

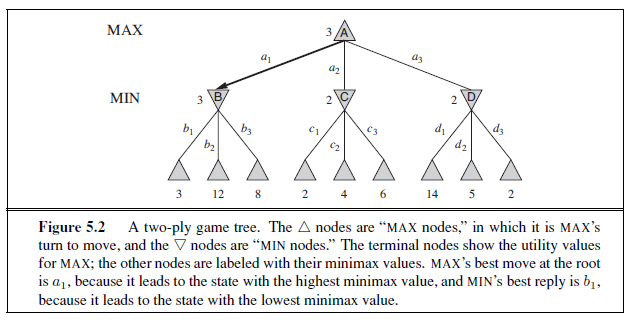

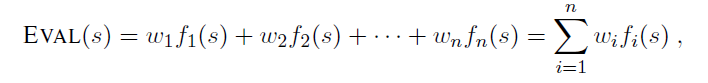

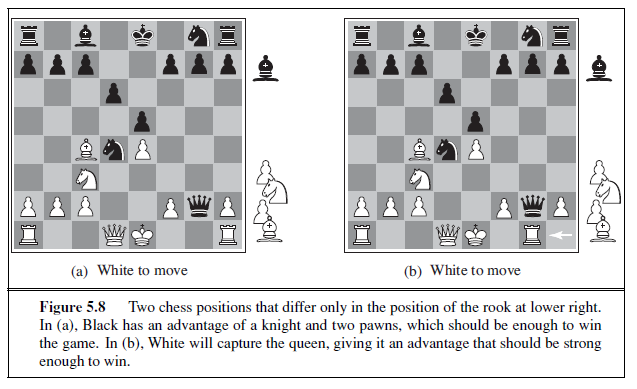

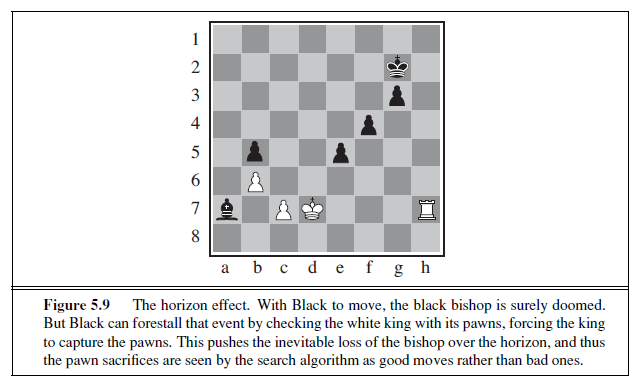

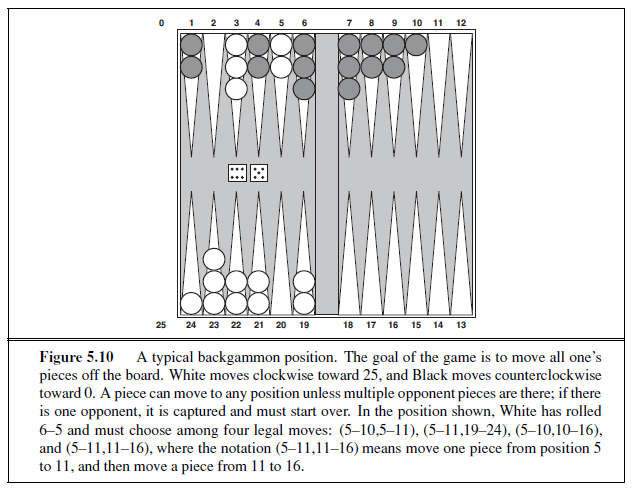

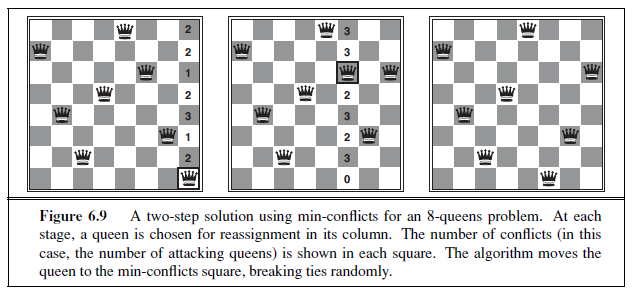

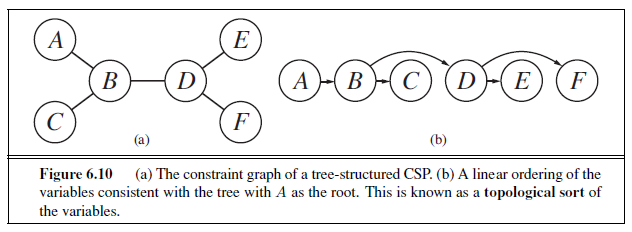

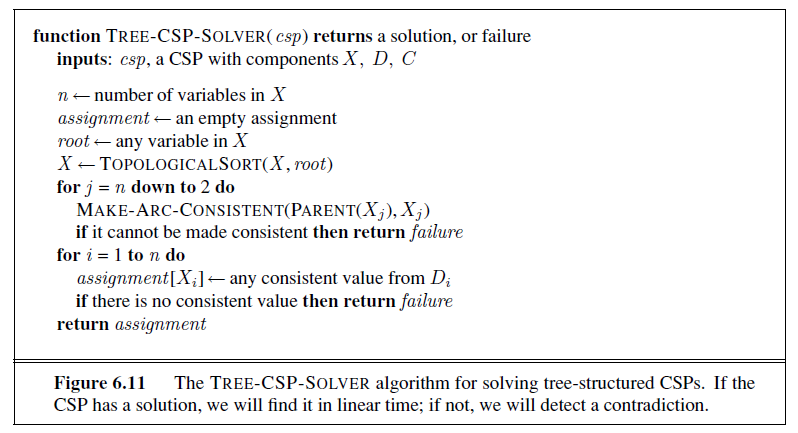

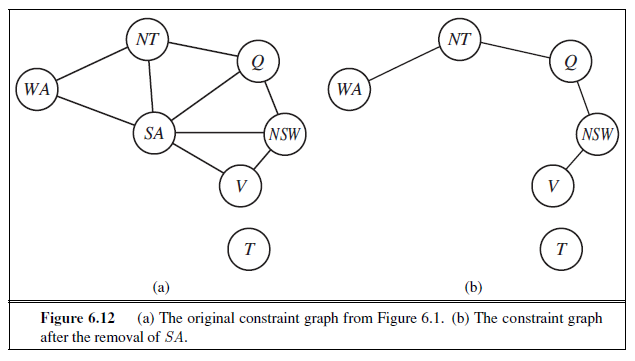

From the two preceding observations, it follows that the sequence of nodes expanded by A∗ using GRAPH-SEARCH is in nondecreasing order of f(n). Hence, the first goal node selected for expansion must be an optimal solution because f is the true cost for goal nodes (which have h= 0) and all later goal nodes will be at least as expensive.