LEARNING FROM EXAMPLES

In which we describe agents that can improve their behavior through diligent study of their own experiences.

An agent is learning if it improves its performance on future tasks after making observations about the world. Learning can range from the trivial, as exhibited by jotting down a phone number, to the profound, as exhibited by Albert Einstein, who inferred a new theory of the universe. In this chapter we will concentrate on one class of learning problem, which seems restricted but actually has vast applicability: from a collection of input–output pairs, learn a function that predicts the output for new inputs.

Why would we want an agent to learn? If the design of the agent can be improved, why wouldn’t the designers just program in that improvement to begin with? There are three main reasons. First, the designers cannot anticipate all possible situations that the agent might find itself in. For example, a robot designed to navigate mazes must learn the layout of each new maze it encounters. Second, the designers cannot anticipate all changes over time; a program designed to predict tomorrow’s stock market prices must learn to adapt when conditions change from boom to bust. Third, sometimes human programmers have no idea how to program a solution themselves. For example, most people are good at recognizing the faces of family members, but even the best programmers are unable to program a computer to accomplish that task, except by using learning algorithms. This chapter first gives an overview of the various forms of learning, then describes one popular approach, decisiontree learning, in Section 18.3, followed by a theoretical analysis of learning in Sections 18.4 and 18.5. We look at various learning systems used in practice: linear models, nonlinear models (in particular, neural networks), nonparametric models, and support vector machines. Finally we show how ensembles of models can outperform a single model.

FORMS OF LEARNING

Any component of an agent can be improved by learning from data. The improvements, and the techniques used to make them, depend on four major factors:

-

Which component is to be improved.

-

What prior knowledge the agent already has.

-

What representation is used for the data and the component.

-

What feedback is available to learn from.

Components to be learned

Chapter 2 described several agent designs. The components of these agents include:

-

A direct mapping from conditions on the current state to actions.

-

A means to infer relevant properties of the world from the percept sequence.

-

Information about the way the world evolves and about the results of possible actions the agent can take.

-

Utility information indicating the desirability of world states.

-

Action-value information indicating the desirability of actions.

-

Goals that describe classes of states whose achievement maximizes the agent’s utility.

Each of these components can be learned. Consider, for example, an agent training to become a taxi driver. Every time the instructor shouts “Brake!” the agent might learn a condition– action rule for when to brake (component 1); the agent also learns every time the instructor does not shout. By seeing many camera images that it is told contain buses, it can learn to recognize them (2). By trying actions and observing the results—for example, braking hard on a wet road—it can learn the effects of its actions (3). Then, when it receives no tip from passengers who have been thoroughly shaken up during the trip, it can learn a useful component of its overall utility function (4).

Representation and prior knowledge

We have seen several examples of representations for agent components: propositional and first-order logical sentences for the components in a logical agent; Bayesian networks for the inferential components of a decision-theoretic agent, and so on. Effective learning algorithms have been devised for all of these representations. This chapter (and most of current machine learning research) covers inputs that form a factored representation—a vector of attribute values—and outputs that can be either a continuous numerical value or a discrete value. Chapter 19 covers functions and prior knowledge composed of first-order logic sentences, and Chapter 20 concentrates on Bayesian networks.

There is another way to look at the various types of learning. We say that learning a (possibly incorrect) general function or rule from specific input–output pairs is called inductive learning. We will see in Chapter 19 that we can also do analytical or deductive learning: going from a known general rule to a new rule that is logically entailed, but is useful because it allows more efficient processing.

Feedback to learn from

There are three types of feedback that determine the three main types of learning: In unsupervised learning the agent learns patterns in the input even though no explicit feedback is supplied. The most common unsupervised learning task is clustering: detecting potentially useful clusters of input examples. For example, a taxi agent might gradually develop a concept of “good traffic days” and “bad traffic days” without ever being given labeled examples of each by a teacher.

In reinforcement learning the agent learns from a series of reinforcements—rewards or punishments. For example, the lack of a tip at the end of the journey gives the taxi agent an indication that it did something wrong. The two points for a win at the end of a chess game tells the agent it did something right. It is up to the agent to decide which of the actions prior to the reinforcement were most responsible for it.

In supervised learning the agent observes some example input–output pairs and learns a function that maps from input to output. In component 1 above, the inputs are percepts and the output are provided by a teacher who says “Brake!” or “Turn left.” In component 2, the inputs are camera images and the outputs again come from a teacher who says “that’s a bus.” In 3, the theory of braking is a function from states and braking actions to stopping distance in feet. In this case the output value is available directly from the agent’s percepts (after the fact); the environment is the teacher.

In practice, these distinction are not always so crisp. In semi-supervised learning we are given a few labeled examples and must make what we can of a large collection of unlabeled examples. Even the labels themselves may not be the oracular truths that we hope for. Imagine that you are trying to build a system to guess a person’s age from a photo. You gather some labeled examples by snapping pictures of people and asking their age. That’s supervised learning. But in reality some of the people lied about their age. It’s not just that there is random noise in the data; rather the inaccuracies are systematic, and to uncover them is an unsupervised learning problem involving images, self-reported ages, and true (unknown) ages. Thus, both noise and lack of labels create a continuum between supervised and unsupervised learning.

SUPERVISED LEARNING

The task of supervised learning is this:

Given a training set of N example input–output pairsTRAINING SET

(x~1~, y~1~), (x~2~, y~2~), . . . (x~N~ , y~N~ ) ,

where each y~j~ was generated by an unknown function y = f(x), discover a function h that approximates the true function f .

Here x and y can be any value; they need not be numbers. The function h is a hypothesis.1 Learning is a search through the space of possible hypotheses for one that will perform well, even on new examples beyond the training set. To measure the accuracy of a hypothesis we give it a test set of examples that are distinct from the training set. We say a hypothesis

1 A note on notation: except where noted, we will use j to index the N examples; x~j~ will always be the input and y~j~ the output. In cases where the input is specifically a vector of attribute values (beginning with Section 18.3), we will use x~j~ for the jth example and we will use i to index the n attributes of each example. The elements of x~j~ are written x~j,1~, x~j,2~, . . . , x~j,n~.

generalizes well if it correctly predicts the value of y for novel examples. Sometimes the function f is stochastic—it is not strictly a function of x, and what we have to learn is a conditional probability distribution, P(Y | x).

When the output y is one of a finite set of values (such as sunny, cloudy or rainy), the learning problem is called classification, and is called Boolean or binary classification if there are only two values. When y is a number (such as tomorrow’s temperature), the learning problem is called regression. (Technically, solving a regression problem is finding a conditional expectation or average value of y, because the probability that we have found exactly the right real-valued number for y is 0.)

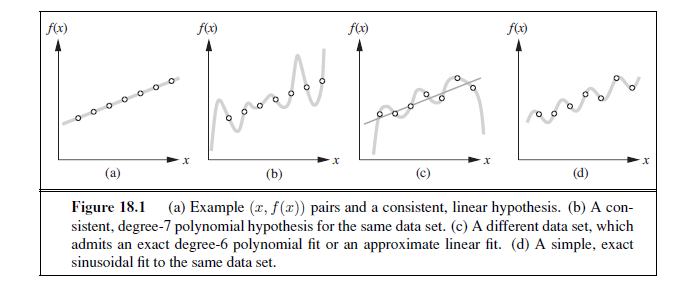

Figure 18.1 shows a familiar example: fitting a function of a single variable to some data points. The examples are points in the (x, y) plane, where y = f(x). We don’t know what f is, but we will approximate it with a function h selected from a hypothesis space, H, which for this example we will take to be the set of polynomials, such as x^5^+3x^2^+2. Figure 18.1(a) shows some data with an exact fit by a straight line (the polynomial 0.4x + 3). The line is called a consistent hypothesis because it agrees with all the data. Figure 18.1(b) shows a high-degree polynomial that is also consistent with the same data. This illustrates a fundamental problem in inductive learning: how do we choose from among multiple consistent hypotheses? One answer is to prefer the simplest hypothesis consistent with the data. This principle is called Ockham’s razor, after the 14th-century English philosopher William of Ockham, who used it to argue sharply against all sorts of complications. Defining simplicity is not easy, but it seems clear that a degree-1 polynomial is simpler than a degree-7 polynomial, and thus (a) should be preferred to (b). We will make this intuition more precise in Section 18.4.3.

Figure 18.1(c) shows a second data set. There is no consistent straight line for this data set; in fact, it requires a degree-6 polynomial for an exact fit. There are just 7 data points, so a polynomial with 7 parameters does not seem to be finding any pattern in the data and we do not expect it to generalize well. A straight line that is not consistent with any of the data points, but might generalize fairly well for unseen values of x, is also shown in (c). In general, there is a tradeoff between complex hypotheses that fit the training data well and simpler hypotheses that may generalize better. In Figure 18.1(d) we expand the hypothesis space H to allow polynomials over both x and sin(x), and find that the data in (c) can be fitted exactly by a simple function of the form ax + b + c sin(x). This shows the importance of the choice of hypothesis space. We say that a learning problem is realizable if the hypothesis space contains the true function. Unfortunately, we cannot always tell whether a given learning problem is realizable, because the true function is not known.

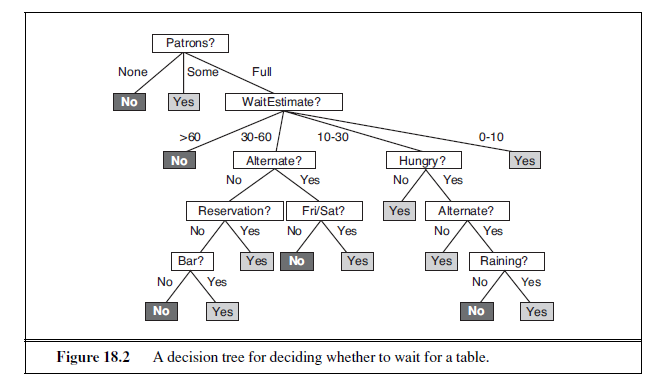

In some cases, an analyst looking at a problem is willing to make more fine-grained distinctions about the hypothesis space, to say—even before seeing any data—not just that a hypothesis is possible or impossible, but rather how probable it is. Supervised learning can be done by choosing the hypothesis h^∗^that is most probable given the data:

Then we can say that the prior probability P (h) is high for a degree-1 or -2 polynomial, lower for a degree-7 polynomial, and especially low for degree-7 polynomials with large, sharp spikes as in Figure 18.1(b). We allow unusual-looking functions when the data say we really need them, but we discourage them by giving them a low prior probability.

Why not let H be the class of all Java programs, or Turing machines? After all, every computable function can be represented by some Turing machine, and that is the best we can do. One problem with this idea is that it does not take into account the computational complexity of learning. There is a tradeoff between the expressiveness of a hypothesis space and the complexity of finding a good hypothesis within that space. For example, fitting a straight line to data is an easy computation; fitting high-degree polynomials is somewhat harder; and fitting Turing machines is in general undecidable. A second reason to prefer simple hypothesis spaces is that presumably we will want to use h after we have learned it, and computing h(x) when h is a linear function is guaranteed to be fast, while computing an arbitrary Turing machine program is not even guaranteed to terminate. For these reasons, most work on learning has focused on simple representations.

We will see that the expressiveness–complexity tradeoff is not as simple as it first seems: it is often the case, as we saw with first-order logic in Chapter 8, that an expressive language makes it possible for a simple hypothesis to fit the data, whereas restricting the expressiveness of the language means that any consistent hypothesis must be very complex. For example, the rules of chess can be written in a page or two of first-order logic, but require thousands of pages when written in propositional logic.

LEARNING DECISION TREES

Decision tree induction is one of the simplest and yet most successful forms of machine learning. We first describe the representation—the hypothesis space—and then show how to learn a good hypothesis.

The decision tree representation

A decision tree represents a function that takes as input a vector of attribute values and returns a “decision”—a single output value. The input and output values can be discrete or continuous. For now we will concentrate on problems where the inputs have discrete values and the output has exactly two possible values; this is Boolean classification, where each example input will be classified as true (a positive example) or false (a negative example).

A decision tree reaches its decision by performing a sequence of tests. Each internal node in the tree corresponds to a test of the value of one of the input attributes, Ai, and the branches from the node are labeled with the possible values of the attribute, Ai = vik. Each leaf node in the tree specifies a value to be returned by the function. The decision tree representation is natural for humans; indeed, many “How To” manuals (e.g., for car repair) are written entirely as a single decision tree stretching over hundreds of pages.

As an example, we will build a decision tree to decide whether to wait for a table at a restaurant. The aim here is to learn a definition for the goal predicate WillWait . First we list the attributes that we will consider as part of the input:

-

Alternate: whether there is a suitable alternative restaurant nearby.

-

Bar : whether the restaurant has a comfortable bar area to wait in.

-

Fri/Sat : true on Fridays and Saturdays.

-

Hungry: whether we are hungry.

-

Patrons : how many people are in the restaurant (values are None, Some , and Full ).

-

Price: the restaurant’s price range ($, $$, $$$). 7. Raining : whether it is raining outside.

-

Reservation : whether we made a reservation.

-

Type: the kind of restaurant (French, Italian, Thai, or burger).

-

WaitEstimate: the wait estimated by the host (0–10 minutes, 10–30, 30–60, or >60).

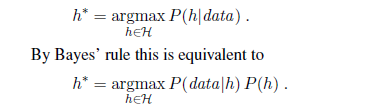

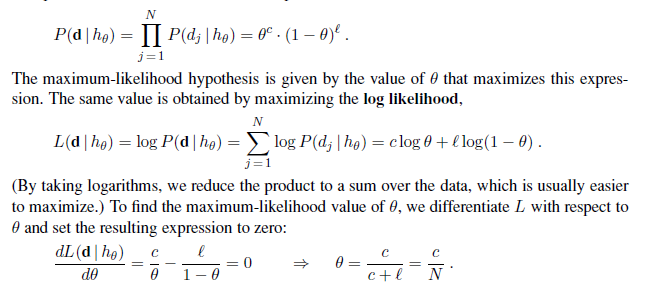

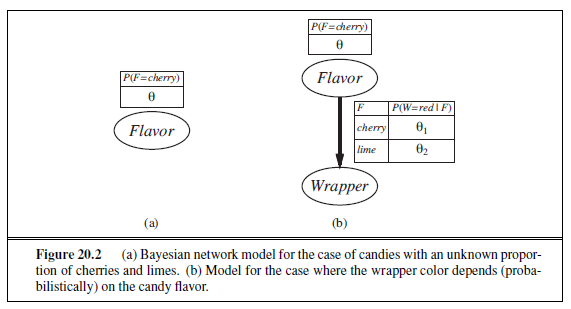

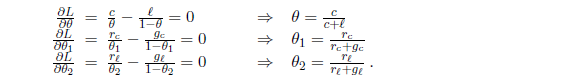

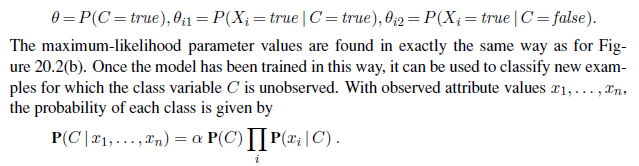

Note that every variable has a small set of possible values; the value of WaitEstimate , for example, is not an integer, rather it is one of the four discrete values 0–10, 10–30, 30–60, or >60. The decision tree usually used by one of us (SR) for this domain is shown in Figure 18.2. Notice that the tree ignores the Price and Type attributes. Examples are processed by the tree starting at the root and following the appropriate branch until a leaf is reached. For instance, an example with Patrons =Full and WaitEstimate = 0–10 will be classified as positive (i.e., yes, we will wait for a table).

Expressiveness of decision trees

A Boolean decision tree is logically equivalent to the assertion that the goal attribute is true if and only if the input attributes satisfy one of the paths leading to a leaf with value true . Writing this out in propositional logic, we have

Goal ⇔ (Path~1~ ∨ Path~2~ ∨ · · ·) ,

where each Path is a conjunction of attribute-value tests required to follow that path. Thus, the whole expression is equivalent to disjunctive normal form (see page 283), which means that any function in propositional logic can be expressed as a decision tree. As an example, the rightmost path in Figure 18.2 is

Path = (Patrons =Full ∧WaitEstimate = 0–10) .

For a wide variety of problems, the decision tree format yields a nice, concise result. But some functions cannot be represented concisely. For example, the majority function, which returns true if and only if more than half of the inputs are true, requires an exponentially large decision tree. In other words, decision trees are good for some kinds of functions and bad for others. Is there any kind of representation that is efficient for all kinds of functions? Unfortunately, the answer is no. We can show this in a general way. Consider the set of all Boolean functions on n attributes. How many different functions are in this set? This is just the number of different truth tables that we can write down, because the function is defined by its truth table. A truth table over n attributes has 2n rows, one for each combination of values of the attributes. We can consider the “answer” column of the table as a 2n-bit number that defines the function. That means there are 22n different functions (and there will be more than that number of trees, since more than one tree can compute the same function). This is a scary number. For example, with just the ten Boolean attributes of our restaurant problem there are 21024 or about 10308 different functions to choose from, and for 20 attributes there are over 10300,000. We will need some ingenious algorithms to find good hypotheses in such a large space.

Inducing decision trees from examples

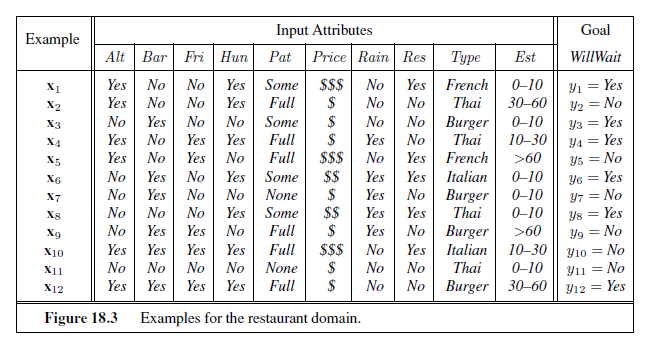

An example for a Boolean decision tree consists of an (x, y) pair, where x is a vector of values for the input attributes, and y is a single Boolean output value. A training set of 12 examples

is shown in Figure 18.3. The positive examples are the ones in which the goal WillWait is true (x~1~, x~3~, . . .); the negative examples are the ones in which it is false (x~2~, x~5~, . . .).

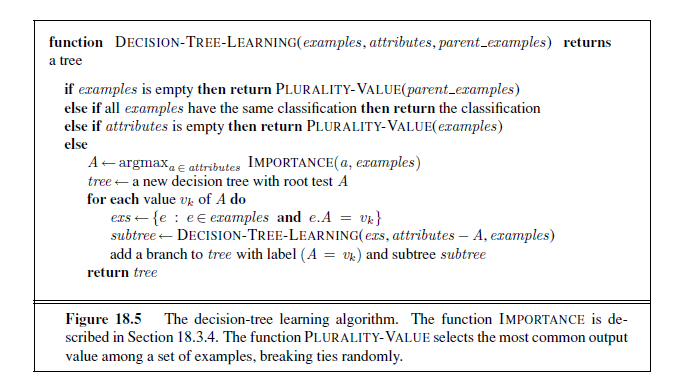

We want a tree that is consistent with the examples and is as small as possible. Unfortunately, no matter how we measure size, it is an intractable problem to find the smallest consistent tree; there is no way to efficiently search through the 22n trees. With some simple heuristics, however, we can find a good approximate solution: a small (but not smallest) consistent tree. The DECISION-TREE-LEARNING algorithm adopts a greedy divide-and-conquer strategy: always test the most important attribute first. This test divides the problem up into smaller subproblems that can then be solved recursively. By “most important attribute,” we mean the one that makes the most difference to the classification of an example. That way, we hope to get to the correct classification with a small number of tests, meaning that all paths in the tree will be short and the tree as a whole will be shallow.

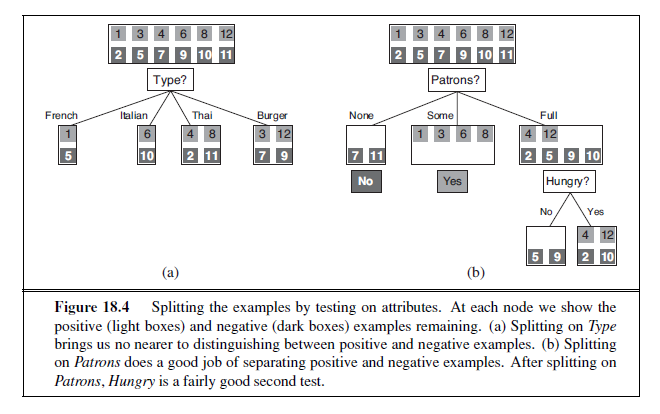

Figure 18.4(a) shows that Type is a poor attribute, because it leaves us with four possible outcomes, each of which has the same number of positive as negative examples. On the other hand, in (b) we see that Patrons is a fairly important attribute, because if the value is None or Some , then we are left with example sets for which we can answer definitively (No and Yes , respectively). If the value is Full , we are left with a mixed set of examples. In general, after the first attribute test splits up the examples, each outcome is a new decision tree learning problem in itself, with fewer examples and one less attribute. There are four cases to consider for these recursive problems:

-

If the remaining examples are all positive (or all negative), then we are done: we can answer Yes or No. Figure 18.4(b) shows examples of this happening in the None and Some branches.

-

If there are some positive and some negative examples, then choose the best attribute to split them. Figure 18.4(b) shows Hungry being used to split the remaining examples.

-

If there are no examples left, it means that no example has been observed for this com

bination of attribute values, and we return a default value calculated from the plurality classification of all the examples that were used in constructing the node’s parent. These are passed along in the variable parent examples .

- If there are no attributes left, but both positive and negative examples, it means that these examples have exactly the same description, but different classifications. This can happen because there is an error or noise in the data; because the domain is nondeter-ministic; or because we can’t observe an attribute that would distinguish the examples. The best we can do is return the plurality classification of the remaining examples.

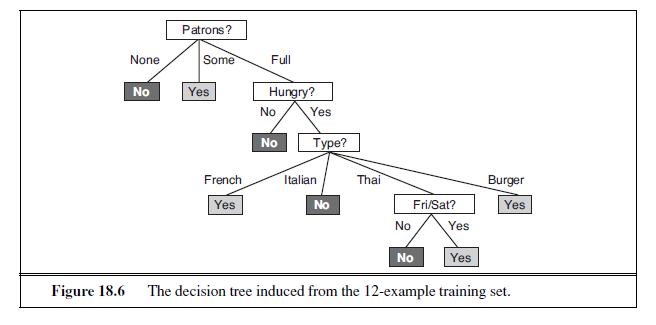

The DECISION-TREE-LEARNING algorithm is shown in Figure 18.5. Note that the set of examples is crucial for constructing the tree, but nowhere do the examples appear in the tree itself. A tree consists of just tests on attributes in the interior nodes, values of attributes on the branches, and output values on the leaf nodes. The details of the IMPORTANCE function are given in Section 18.3.4. The output of the learning algorithm on our sample training set is shown in Figure 18.6. The tree is clearly different from the original tree shown in Figure 18.2. One might conclude that the learning algorithm is not doing a very good job of learning the correct function. This would be the wrong conclusion to draw, however. The learning algorithm looks at the examples, not at the correct function, and in fact, its hypothesis (see Figure 18.6) not only is consistent with all the examples, but is considerably simpler than the original tree! The learning algorithm has no reason to include tests for Raining and Reservation , because it can classify all the examples without them. It has also detected an interesting and previously unsuspected pattern: the first author will wait for Thai food on weekends. It is also bound to make some mistakes for cases where it has seen no examples. For example, it has never seen a case where the wait is 0–10 minutes but the restaurant is full.

In that case it says not to wait when Hungry is false, but I (SR) would certainly wait. With more training examples the learning program could correct this mistake.

We note there is a danger of over-interpreting the tree that the algorithm selects. When there are several variables of similar importance, the choice between them is somewhat arbitrary: with slightly different input examples, a different variable would be chosen to split on first, and the whole tree would look completely different. The function computed by the tree would still be similar, but the structure of the tree can vary widely.

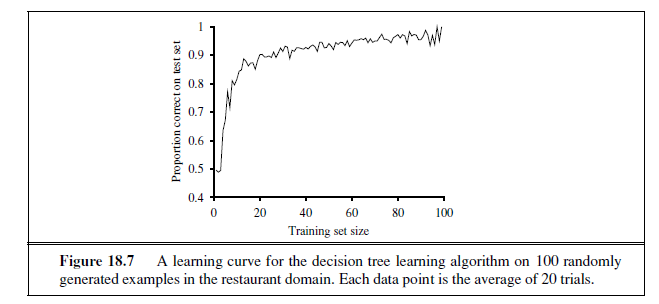

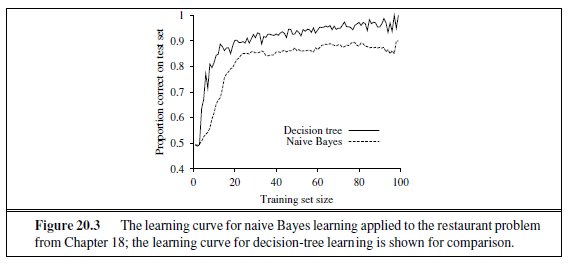

We can evaluate the accuracy of a learning algorithm with a learning curve, as shown in Figure 18.7. We have 100 examples at our disposal, which we split into a training set and

a test set. We learn a hypothesis h with the training set and measure its accuracy with the test set. We do this starting with a training set of size 1 and increasing one at a time up to size 99. For each size we actually repeat the process of randomly splitting 20 times, and average the results of the 20 trials. The curve shows that as the training set size grows, the accuracy increases. (For this reason, learning curves are also called happy graphs.) In this graph we reach 95% accuracy, and it looks like the curve might continue to increase with more data.

Choosing attribute tests

The greedy search used in decision tree learning is designed to approximately minimize the depth of the final tree. The idea is to pick the attribute that goes as far as possible toward providing an exact classification of the examples. A perfect attribute divides the examples into sets, each of which are all positive or all negative and thus will be leaves of the tree. The Patrons attribute is not perfect, but it is fairly good. A really useless attribute, such as Type , leaves the example sets with roughly the same proportion of positive and negative examples as the original set.

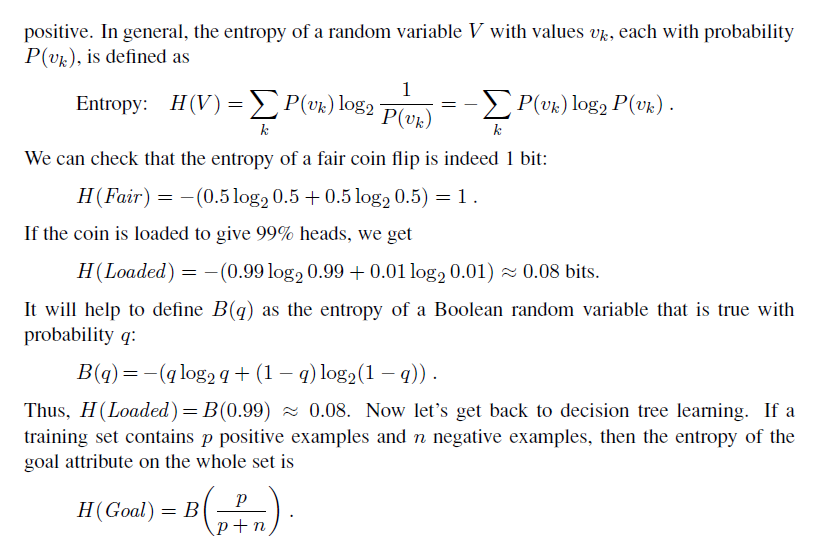

All we need, then, is a formal measure of “fairly good” and “really useless” and we can implement the IMPORTANCE function of Figure 18.5. We will use the notion of information gain, which is defined in terms of entropy, the fundamental quantity in information theo (Shannon and Weaver, 1949). Entropy is a measure of the uncertainty of a random variable; acquisition of information corresponds to a reduction in entropy. A random variable with only one value—a coin that always comes up heads—has no uncertainty and thus its entropy is defined as zero; thus, we gain no information by observing its value. A flip of a fair coin is equally likely to come up heads or tails, 0 or 1, and we will soon show that this counts as “1 bit” of entropy. The roll of a fair four-sided die has 2 bits of entropy, because it takes two bits to describe one of four equally probable choices. Now consider an unfair coin that comes up heads 99% of the time. Intuitively, this coin has less uncertainty than the fair coin—if we guess heads we’ll be wrong only 1% of the time—so we would like it to have an entropy measure that is close to zero, but positive. In general, the entropy of a random variable V with values vk, each with probability P (vk), is defined as

Generalization and overfitting

On some problems, the DECISION-TREE-LEARNING algorithm will generate a large tree when there is actually no pattern to be found. Consider the problem of trying to predict whether the roll of a die will come up as 6 or not. Suppose that experiments are carried out with various dice and that the attributes describing each training example include the color of the die, its weight, the time when the roll was done, and whether the experimenters had their fingers crossed. If the dice are fair, the right thing to learn is a tree with a single node that says “no,” But the DECISION-TREE-LEARNING algorithm will seize on any pattern it can find in the input. If it turns out that there are 2 rolls of a 7-gram blue die with fingers crossed and they both come out 6, then the algorithm may construct a path that predicts 6 in that case. This problem is called overfitting. A general phenomenon, overfitting occurs with all types of learners, even when the target function is not at all random. In Figure 18.1(b) and (c), we saw polynomial functions overfitting the data. Overfitting becomes more likely as the hypothesis space and the number of input attributes grows, and less likely as we increase the number of training examples.

For decision trees, a technique called decision tree pruning combats overfitting. Pruning works by eliminating nodes that are not clearly relevant. We start with a full tree, as generated by DECISION-TREE-LEARNING. We then look at a test node that has only leaf nodes as descendants. If the test appears to be irrelevant—detecting only noise in the data— then we eliminate the test, replacing it with a leaf node. We repeat this process, considering each test with only leaf descendants, until each one has either been pruned or accepted as is.

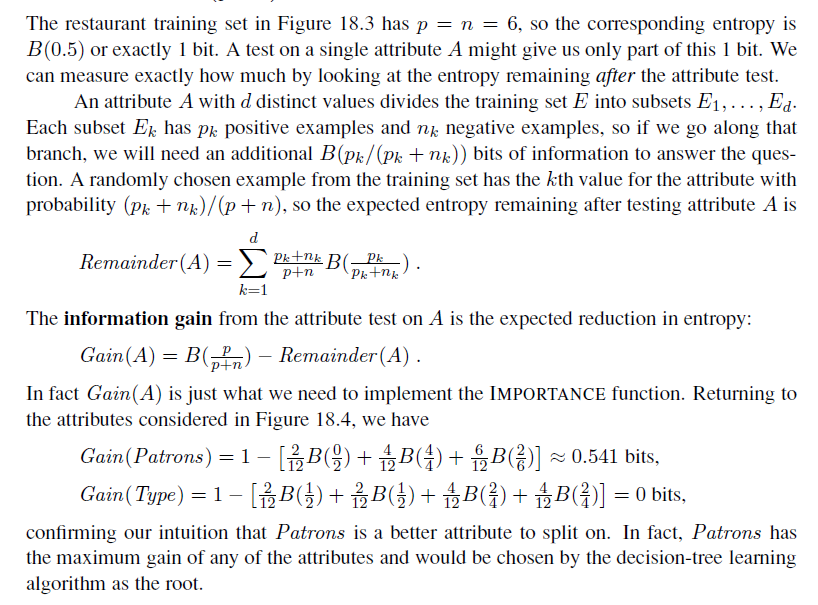

The question is, how do we detect that a node is testing an irrelevant attribute? Suppose we are at a node consisting of p positive and n negative examples. If the attribute is irrelevant, we would expect that it would split the examples into subsets that each have roughly the same proportion of positive examples as the whole set, p/(p + n), and so the information gain will be close to zero.2 Thus, the information gain is a good clue to irrelevance. Now the question is, how large a gain should we require in order to split on a particular attribute?

We can answer this question by using a statistical significance test. Such a test begins by assuming that there is no underlying pattern (the so-called null hypothesis). Then the actual data are analyzed to calculate the extent to which they deviate from a perfect absence of pattern. If the degree of deviation is statistically unlikely (usually taken to mean a 5% probability or less), then that is considered to be good evidence for the presence of a significant pattern in the data. The probabilities are calculated from standard distributions of the amount of deviation one would expect to see in random sampling.

In this case, the null hypothesis is that the attribute is irrelevant and, hence, that the information gain for an infinitely large sample would be zero. We need to calculate the probability that, under the null hypothesis, a sample of size v = n + p would exhibit the observed deviation from the expected distribution of positive and negative examples. We can measure the deviation by comparing the actual numbers of positive and negative examples in

2 The gain will be strictly positive except for the unlikely case where all the proportions are exactly the same. (See Exercise 18.5.)

each subset, pk and nk, with the expected numbers, p̂k and n̂k, assuming true irrelevance:

Under the null hypothesis, the value of Δ is distributed according to the χ 2 (chi-squared) distribution with v − 1 degrees of freedom. We can use a χ 2 table or a standard statistical library routine to see if a particular Δ value confirms or rejects the null hypothesis. For example, consider the restaurant type attribute, with four values and thus three degrees of freedom. A value of Δ = 7.82 or more would reject the null hypothesis at the 5% level (and a value of Δ = 11.35 or more would reject at the 1% level). Exercise 18.8 asks you to extend the DECISION-TREE-LEARNING algorithm to implement this form of pruning, which is known as χ2 pruning.χ 2 With pruning, noise in the examples can be tolerated. Errors in the example’s label (e.g., an example (x,Yes) that should be (x,No)) give a linear increase in prediction error, whereas errors in the descriptions of examples (e.g., Price = $ when it was actually Price = $$) have an asymptotic effect that gets worse as the tree shrinks down to smaller sets. Pruned trees perform significantly better than unpruned trees when the data contain a large amount of noise. Also, the pruned trees are often much smaller and hence easier to understand.

One final warning: You might think that χ 2 pruning and information gain look similar,so why not combine them using an approach called early stopping—have the decision tree algorithm stop generating nodes when there is no good attribute to split on, rather than going to all the trouble of generating nodes and then pruning them away. The problem with early stopping is that it stops us from recognizing situations where there is no one good attribute, but there are combinations of attributes that are informative. For example, consider the XOR function of two binary attributes. If there are roughly equal number of examples for all four combinations of input values, then neither attribute will be informative, yet the correct thing to do is to split on one of the attributes (it doesn’t matter which one), and then at the second level we will get splits that are informative. Early stopping would miss this, but generateand-then-prune handles it correctly.

Broadening the applicability of decision trees

In order to extend decision tree induction to a wider variety of problems, a number of issues must be addressed. We will briefly mention several, suggesting that a full understanding is best obtained by doing the associated exercises:

-

Missing data: In many domains, not all the attribute values will be known for every example. The values might have gone unrecorded, or they might be too expensive to obtain. This gives rise to two problems: First, given a complete decision tree, how should one classify an example that is missing one of the test attributes? Second, how should one modify the information-gain formula when some examples have unknown values for the attribute? These questions are addressed in Exercise 18.9.

-

Multivalued attributes: When an attribute has many possible values, the information gain measure gives an inappropriate indication of the attribute’s useful^n^ess. In the extreme case, an attribute such as ExactTime has a different value for every example, which means each subset of examples is a singleton with a unique classification, and the information gain measure would have its highest value for this attribute. But choosing this split first is unlikely to yield the best tree. One solution is to use the gain ratio (Exercise 18.10). Another possibility is to allow a Boolean test of the form A= vk, that is, picking out just one of the possible values for an attribute, leaving the remaining values to possibly be tested later in the tree.

-

Continuous and integer-valued input attributes: Continuous or integer-valued attributes such as Height and Weight , have an infinite set of possible values. Rather than generate infinitely many branches, decision-tree learning algorithms typically find the split point that gives the highest information gain. For example, at a given node in the tree, it might be the case that testing on Weight > 160 gives the most information. Efficient methods exist for finding good split points: start by sorting the values of the attribute, and then consider only split points that are between two examples in sorted order that have different classifications, while keeping track of the running totals of positive and negative examples on each side of the split point. Splitting is the most expensive part of real-world decision tree learning applications.

-

Continuous-valued output attributes: If we are trying to predict a numerical output value, such as the price of an apartment, then we need a regression tree rather than a classification tree. A regression tree has at each leaf a linear function of some subset of numerical attributes, rather than a single value. For example, the branch for twobedroom apartments might end with a linear function of square footage, number of bathrooms, and average income for the neighborhood. The learning algorithm must decide when to stop splitting and begin applying linear regression (see Section 18.6) over the attributes.

A decision-tree learning system for real-world applications must be able to handle all of these problems. Handling continuous-valued variables is especially important, because both physical and financial processes provide numerical data. Several commercial packages have been built that meet these criteria, and they have been used to develop thousands of fielded systems. In many areas of industry and commerce, decision trees are usually the first method tried when a classification method is to be extracted from a data set. One important property of decision trees is that it is possible for a human to understand the reason for the output of the learning algorithm. (Indeed, this is a legal requirement for financial decisions that are subject to anti-discrimination laws.) This is a property not shared by some other representations, such as neural networks.

EVALUATING AND CHOOSING THE BEST HYPOTHESIS

We want to learn a hypothesis that fits the future data best. To make that precise we need to define “future data” and “best.” We make the stationarity assumption: that there is a probability distribution over examples that remains stationary over time. Each example data point (before we see it) is a random variable Ej whose observed value ej = (x~j~, y~j~) is sampled from that distribution, and is independent of the previous examples:

P(E~j~ |E~j−1~, E~j−2~, . . .) = P(E~j~) ,

and each example has an identical prior probability distribution:

P(E~j~) = P(E~j−1~) = P(E~j−2~) = · · · .

Examples that satisfy these assumptions are called independent and identically distributed or i.i.d.. An i.i.d. assumption connects the past to the future; without some such connection, allbets are off—the future could be anything. (We will see later that learning can still occur if there are slow changes in the distribution.)

The next step is to define “best fit.” We define the error rate of a hypothesis as the proportion of mistakes it makes—the proportion of times that h(x) == y for an (x, y) example. Now, just because a hypothesis h has a low error rate on the training set does not mean that it will generalize well. A professor knows that an exam will not accurately evaluate students if they have already seen the exam questions. Similarly, to get an accurate evaluation of a hypothesis, we need to test it on a set of examples it has not seen yet. The simplest approach is the one we have seen already: randomly split the available data into a training set from which the learning algorithm produces h and a test set on which the accuracy of h is evaluated. This method, sometimes called holdout cross-validation, has the disadvantage that it fails to use all the available data; if we use half the data for the test set, then we are only training on half the data, and we may get a poor hypothesis. On the other hand, if we reserve only 10% of the data for the test set, then we may, by statistical chance, get a poor estimate of the actual accuracy.

We can squeeze more out of the data and still get an accurate estimate using a technique called k -fold cross-validation. The idea is that each example serves double duty—as training K- data and test data. First we split the data into k equal subsets. We then perform k rounds of learning; on each round 1/k of the data is held out as a test set and the remaining examples are used as training data. The average test set score of the k rounds should then be a better estimate than a single score. Popular values for k are 5 and 10—enough to give an estimate that is statistically likely to be accurate, at a cost of 5 to 10 times longer computation time. The extreme is k = n, also known as leave-one-out cross-validation or LOOCV. LOOCV Despite the best efforts of statistical methodologists, users frequently invalidate their results by inadvertently peeking at the test data. Peeking can happen like this: A learning algorithm has various “knobs” that can be twiddled to tune its behavior—for example, various different criteria for choosing the next attribute in decision tree learning. The researcher generates hypotheses for various different settings of the knobs, measures their error rates on the test set, and reports the error rate of the best hypothesis. Alas, peeking has occurred! The reason is that the hypothesis was selected on the basis of its test set error rate, so information about the test set has leaked into the learning algorithm.

Peeking is a consequence of using test-set performance to both choose a hypothesis and evaluate it. The way to avoid this is to really hold the test set out—lock it away until you are completely done with learning and simply wish to obtain an independent evaluation of the final hypothesis. (And then, if you don’t like the results . . . you have to obtain, and lock away, a completely new test set if you want to go back and find a better hypothesis.) If the test set is locked away, but you still want to measure performance on unseen data as a way of selecting a good hypothesis, then divide the available data (without the test set) into a training set and a validation set. The next section shows how to use validation sets to find a good tradeoff between hypothesis complexity and goodness of fit.

Model selection: Complexity versus goodness of fit

In Figure 18.1 (page 696) we showed that higher-degree polynomials can fit the training data better, but when the degree is too high they will overfit, and perform poorly on validation data. Choosing the degree of the polynomial is an instance of the problem of model selection. You can think of the task of finding the best hypothesis as two tasks: model selection defines the hypothesis space and then optimization finds the best hypothesis within that space.In this section we explain how to select among models that are parameterized by size . For example, with polynomials we have size = 1 for linear functions, size = 2 for quadratics, and so on. For decision trees, the size could be the number of nodes in the tree. In all cases we want to find the value of the size parameter that best balances underfitting and overfitting to give the best test set accuracy.

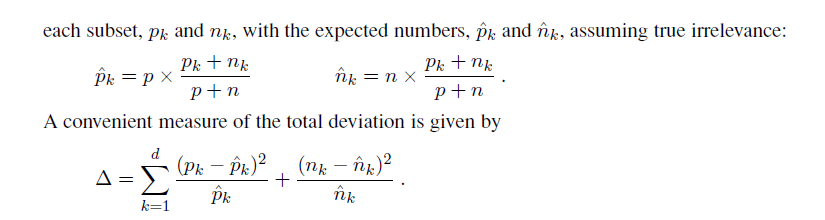

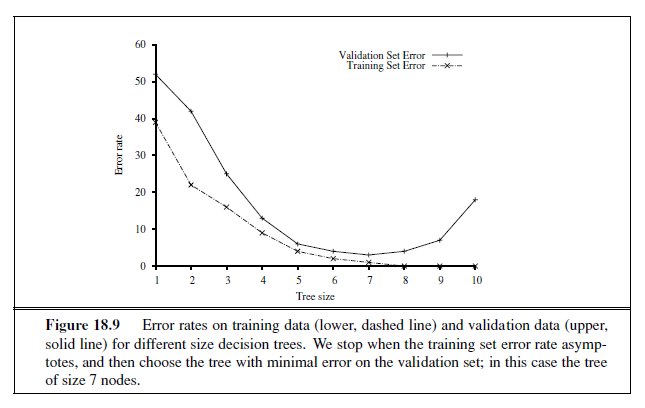

An algorithm to perform model selection and optimization is shown in Figure 18.8. It is a wrapper that takes a learning algorithm as an argument (DECISION-TREE-LEARNING, for example). The wrapper enumerates models according to a parameter, size . For each size, it uses cross validation on Learner to compute the average error rate on the training and test sets. We start with the smallest, simplest models (which probably underfit the data), and iterate, considering more complex models at each step, until the models start to overfit. In Figure 18.9 we see typical curves: the training set error decreases monotonically (although there may in general be slight random variation), while the validation set error decreases at first, and then increases when the model begins to overfit. The cross-validation procedure picks the value of size with the lowest validation set error; the bottom of the U-shaped curve. We then generate a hypothesis of that size , using all the data (without holding out any of it). Finally, of course, we should evaluate the returned hypothesis on a separate test set.

This approach requires that the learning algorithm accept a parameter, size , and deliver a hypothesis of that size. As we said, for decision tree learning, the size can be the number of nodes. We can modify DECISION-TREE-LEARNER so that it takes the number of nodes as an input, builds the tree breadth-first rather than depth-first (but at each level it still chooses the highest gain attribute first), and stops when it reaches the desired number of nodes.

From error rates to loss

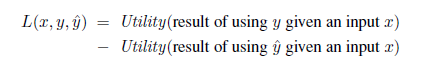

So far, we have been trying to minimize error rate. This is clearly better than maximizing error rate, but it is not the full story. Consider the problem of classifying email messages as spam or non-spam. It is worse to classify non-spam as spam (and thus potentially miss an important message) then to classify spam as non-spam (and thus suffer a few seconds of annoyance). So a classifier with a 1% error rate, where almost all the errors were classifying spam as non-spam, would be better than a classifier with only a 0.5% error rate, if most of those errors were classifying non-spam as spam. We saw in Chapter 16 that decision-makers should maximize expected utility, and utility is what learners should maximize as well. In machine learning it is traditional to express utilities by means of a loss function. The loss function L(x, y, ŷ) is defined as the amount of utility lost by predicting h(x)= ŷ when the correct answer is f(x)= y:

This is the most general formulation of the loss function. Often a simplified version is used, L(y, ŷ), that is independent of x. We will use the simplified version for the rest of this chapter, which means we can’t say that it is worse to misclassify a letter from Mom than it is to misclassify a letter from our annoying cousin, but we can say it is 10 times worse to classify non-spam as spam than vice-versa:

L(spam ,nospam) = 1, L(nospam , spam) = 10 .

Note that L(y, y) is always zero; by definition there is no loss when you guess exactly right. For functions with discrete outputs, we can enumerate a loss value for each possible misclassification, but we can’t enumerate all the possibilities for real-valued data. If f(x) is 137.035999, we would be fairly happy with h(x) = 137.036, but just how happy should we be? In general small errors are better than large ones; two functions that implement that idea are the absolute value of the difference (called the L~1~ loss), and the square of the difference (called the L~2~ loss). If we are content with the idea of minimizing error rate, we can use the L~0/1~ loss function, which has a loss of 1 for an incorrect answer and is appropriate for discrete-valued outputs:

Absolute value loss: L~1~(y, ŷ) = |y − ŷ|

Squared error loss: L~2~(y, ŷ) = (y − ŷ)2

0/1 loss: L~0/1~(y, ŷ) = 0 if y = ŷ, else 1

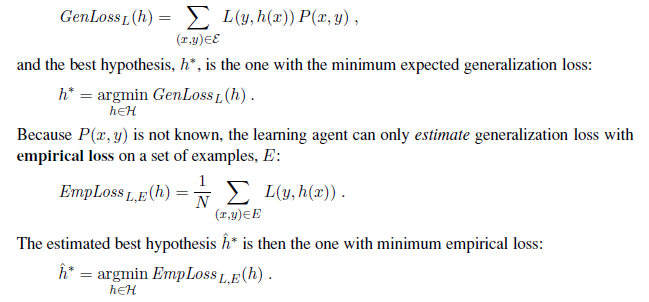

The learning agent can theoretically maximize its expected utility by choosing the hypothesis that minimizes expected loss over all input–output pairs it will see. It is meaningless to talk about this expectation without defining a prior probability distribution, P(X,Y ) over examples. Let E be the set of all possible input–output examples. Then the expected generalization loss for a hypothesis h (with respect to loss function L) is

There are four reasons why ĥ ∗ may differ from the true function, f : unrealizability, variance noise, and computational complexity. First, f may not be realizable—may not be in H—or may be present in such a way that other hypotheses are preferred. Second, a learning algorithm will return different hypotheses for different sets of examples, even if those sets are drawn from the same true function f , and those hypotheses will make different predictions on new examples. The higher the variance among the predictions, the higher the probability of significant error. Note that even when the problem is realizable, there will still be random variance, but that variance decreases towards zero as the number of training examples increases. Third, f may be nondeterministic or noisy—it may return different values for f(x) each time x occurs. By definition, noise cannot be predicted; in many cases, it arises because the observed labels y are the result of attributes of the environment not listed in x. And finally, when H is complex, it can be computationally intractable to systematically search the whole hypothesis space. The best we can do is a local search (hill climbing or greedy search) that explores only part of the space. That gives us an approximation error. Combining the sources of error, we’re left with an estimation of an approximation of the true function f .

Traditional methods in statistics and the early years of machine learning concentrated on small-scale learning, where the number of training examples ranged from dozens to the low thousands. Here the generalization error mostly comes from the approximation error of not having the true f in the hypothesis space, and from estimation error of not having enough training examples to limit variance. In recent years there has been more emphasis on largescale learning, often with millions of examples. Here the generalization error is dominated by limits of computation: there is enough data and a rich enough model that we could find an h that is very close to the true f , but the computation to find it is too complex, so we settle for a sub-optimal approximation.

Regularization

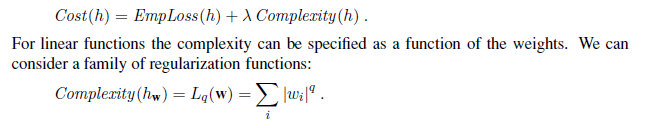

In Section 18.4.1, we saw how to do model selection with cross-validation on model size. An alternative approach is to search for a hypothesis that directly minimizes the weighted sum of empirical loss and the complexity of the hypothesis, which we will call the total cost:

Cost(h) = EmpLoss(h) + λComplexity(h)

ĥ^∗^ = argmin~h∈H~ Cost(h) .

Here λ is a parameter, a positive number that serves as a conversion rate between loss and hypothesis complexity (which after all are not measured on the same scale). This approach combines loss and complexity into one metric, allowing us to find the best hypothesis all at once. Unfortunately we still need to do a cross-validation search to find the hypothesis that generalizes best, but this time it is with different values of λ rather than size . We select the value of λ that gives us the best validation set score.

This process of explicitly penalizing complex hypotheses is called regularization (be- cause it looks for a function that is more regular, or less complex). Note that the cost function requires us to make two choices: the loss function and the complexity measure, which is called a regularization function. The choice of regularization function depends on the hypothesis space. For example, a good regularization function for polynomials is the sum of the squares of the coefficients—keeping the sum small would guide us away from the wiggly polynomials in Figure 18.1(b) and (c). We will show an example of this type of regularization in Section 18.6.

Another way to simplify models is to reduce the dimensions that the models work with. A process of feature selection can be performed to discard attributes that appear to be irrelevant. χ 2 pruning is a kind of feature selection.

It is in fact possible to have the empirical loss and the complexity measured on the same scale, without the conversion factor λ: they can both be measured in bits. First encode the hypothesis as a Turing machine program, and count the number of bits. Then count the number of bits required to encode the data, where a correctly predicted example costs zero bits and the cost of an incorrectly predicted example depends on how large the error is. The minimum description length or MDL hypothesis minimizes the total number of bits required. This works well in the limit, but for smaller problems there is a difficulty in that the choice of encoding for the program—for example, how best to encode a decision tree as a bit string—affects the outcome. In Chapter 20 (page 805), we describe a probabilistic interpretation of the MDL approach.

THE THEORY OF LEARNING

The main unanswered question in learning is this: How can we be sure that our learning algorithm has produced a hypothesis that will predict the correct value for previously unseen inputs? In formal terms, how do we know that the hypothesis h is close to the target function f if we don’t know what f is? These questions have been pondered for several centuries. In more recent decades, other questions have emerged: how many examples do we need to get a good h? What hypothesis space should we use? If the hypothesis space is very complex, can we even find the best h, or do we have to settle for a local maximum in the space of hypotheses? How complex should h be? How do we avoid overfitting? This section examines these questions.

We’ll start with the question of how many examples are needed for learning. We saw from the learning curve for decision tree learning on the restaurant problem (Figure 18.7 on page 703) that improves with more training data. Learning curves are useful, but they are specific to a particular learning algorithm on a particular problem. Are there some more general principles governing the number of examples needed in general? Questions like this are addressed by computational learning theory, which lies at the intersection of AI, statistics, and theoretical computer science. The underlying principle is that any hypothesis that is seriously wrong will almost certainly be “found out” with high probability after a small number of examples, because it will make an incorrect prediction. Thus, any hypothesis that is consistent with a sufficiently large set of training examples is unlikely to be seriously wrong: that is, it must be probably approximately correct. Any learning algorithm that returns hypotheses that are probably approximately correct is called a PAC learning algorithm; we can use this approach to provide bounds on the performance of various learning algorithms. PAC-learning theorems, like all theorems, are logical consequences of axioms. When a theorem (as opposed to, say, a political pundit) states something about the future based on the past, the axioms have to provide the “juice” to make that connection. For PAC learning, the juice is provided by the stationarity assumption introduced on page 708, which says that future examples are going to be drawn from the same fixed distribution P(E)= P(X,Y ) as past examples. (Note that we do not have to know what distribution that is, just that it doesn’t change.) In addition, to keep things simple, we will assume that the true function f is deterministic and is a member of the hypothesis class H that is being considered. The simplest PAC theorems deal with Boolean functions, for which the 0/1 loss is appropriate. The error rate of a hypothesis h, defined informally earlier, is defined formally here as the expected generalization error for examples drawn from the stationary distribution:

error(h) = GenLoss~L~0/1~~ (h) = ∑~x,y~ L~0/1~(y, h(x))P (x, y) .

In other words, error(h) is the probability that h misclassifies a new example. This is the same quantity being measured experimentally by the learning curves shown earlier.

A hypothesis h is called approximately correct if error(h) ≤ ε, where ε is a small constant. We will show that we can find an N such that, after seeing N examples, with high probability, all consistent hypotheses will be approximately correct. One can think of an approximately correct hypothesis as being “close” to the true function in hypothesis space: it lies inside what is called the ε**-ball** around the true function f . The hypothesis space outsideε-BALL this ball is called H~bad~.

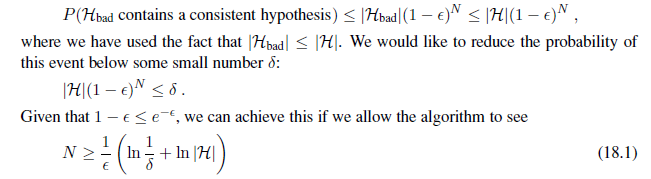

We can calculate the probability that a “seriously wrong” hypothesis hb ∈ Hbad is consistent with the first N examples as follows. We know that error(hb) > ε. Thus, the probability that it agrees with a given example is at most 1 − ε. Since the examples are independent, the bound for N examples is

P (h~b~ agrees with N examples) ≤ (1− ε)^N^

The probability that Hbad contains at least one consistent hypothesis is bounded by the sum of the individual probabilities:

examples. Thus, if a learning algorithm returns a hypothesis that is consistent with this many examples, then with probability at least 1 − δ, it has error at most ε. In other words, it is probably approximately correct. The number of required examples, as a function of ε and δ, is called the sample complexity of the hypothesis space.

As we saw earlier, if H is the set of all Boolean functions on n attributes, then |H| = 2~2~n. Thus, the sample complexity of the space grows as 2n. Because the number of possible examples is also 2n, this suggests that PAC-learning in the class of all Boolean functions requires seeing all, or nearly all, of the possible examples. A moment’s thought reveals the reason for this: H contains enough hypotheses to classify any given set of examples in all possible ways. In particular, for any set of N examples, the set of hypotheses consistent with those examples contains equal numbers of hypotheses that predict xN+1 to be positive and hypotheses that predict xN+1 to be negative.

To obtain real generalization to unseen examples, then, it seems we need to restrict the hypothesis space H in some way; but of course, if we do restrict the space, we might eliminate the true function altogether. There are three ways to escape this dilemma. The first, which we will cover in Chapter 19, is to bring prior knowledge to bear on the problem. The second, which we introduced in Section 18.4.3, is to insist that the algorithm return not just any consistent hypothesis, but preferably a simple one (as is done in decision tree learning). In cases where finding simple consistent hypotheses is tractable, the sample complexity results are generally better than for analyses based only on consistency. The third escape, which we pursue next, is to focus on learnable subsets of the entire hypothesis space of Boolean functions. This approach relies on the assumption that the restricted language contains a hypothesis h that is close enough to the true function f ; the benefits are that the restricted hypothesis space allows for effective generalization and is typically easier to search. We now examine one such restricted language in more detail.

PAC learning example: Learning decision lists

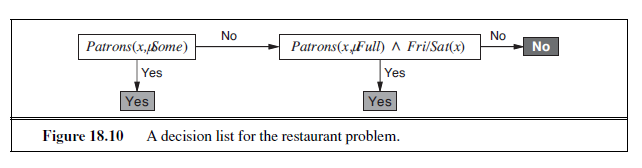

We now show how to apply PAC learning to a new hypothesis space: decision lists.decision list consists of a series of tests, each of which is a conjunction of literals. If a test succeeds when applied to an example description, the decision list specifies the value to be returned. If the test fails, processing continues with the next test in the list. Decision lists resemble decision trees, but their overall structure is simpler: they branch only in one

direction. In contrast, the individual tests are more complex. Figure 18.10 shows a decision list that represents the following hypothesis:

WillWait ⇔ (Patrons = Some) ∨ (Patrons = Full ∧ Fri/Sat) .

If we allow tests of arbitrary size, then decision lists can represent any Boolean function (Exercise 18.14). On the other hand, if we restrict the size of each test to at most k literals, then it is possible for the learning algorithm to generalize successfully from a small number of examples. We call this language k**-DL**. The example in Figure 18.10 is in 2-DL. It is easy tok-DL show (Exercise 18.14) that k-DL includes as a subset the language k**-DT**, the set of all decisionk-DT trees of depth at most k. It is important to remember that the particular language referred to by k-DL depends on the attributes used to describe the examples. We will use the notation k-DL(n) to denote a k-DL language using n Boolean attributes.

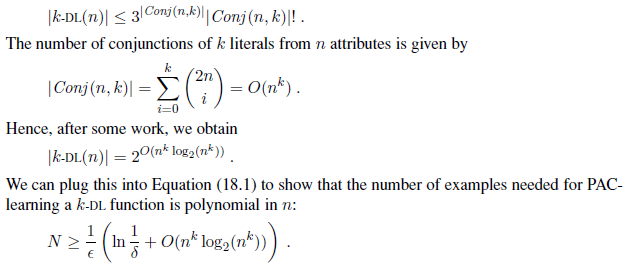

The first task is to show that k-DL is learnable—that is, that any function in k-DL can be approximated accurately after training on a reasonable number of examples. To do this, we need to calculate the number of hypotheses in the language. Let the language of tests— conjunctions of at most k literals using n attributes—be Conj (n, k). Because a decision list is constructed of tests, and because each test can be attached to either a Yes or a No outcome or can be absent from the decision list, there are at most 3|Conj (n,k)| distinct sets of component tests. Each of these sets of tests can be in any order, so

Therefore, any algorithm that returns a consistent decision list will PAC-learn a k-DL function in a reasonable number of examples, for small k.

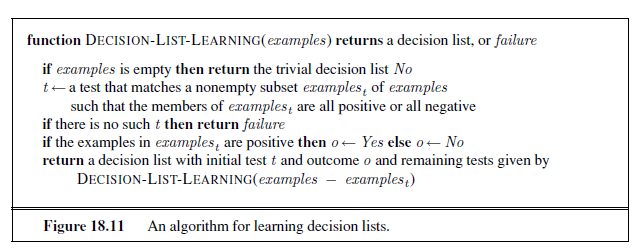

The next task is to find an efficient algorithm that returns a consistent decision list. We will use a greedy algorithm called DECISION-LIST-LEARNING that repeatedly finds a

test that agrees exactly with some subset of the training set. Once it finds such a test, it adds it to the decision list under construction and removes the corresponding examples. It then constructs the remainder of the decision list, using just the remaining examples. This is repeated until there are no examples left. The algorithm is shown in Figure 18.11.

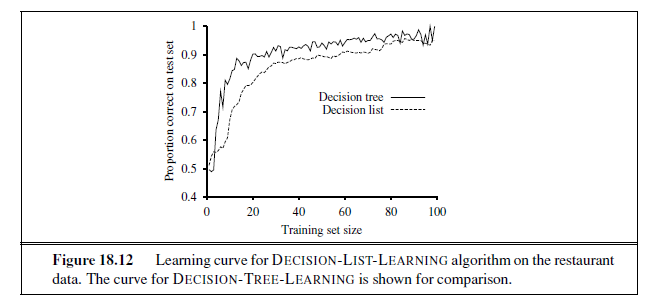

This algorithm does not specify the method for selecting the next test to add to the decision list. Although the formal results given earlier do not depend on the selection method, it would seem reasonable to prefer small tests that match large sets of uniformly classified examples, so that the overall decision list will be as compact as possible. The simplest strategy is to find the smallest test t that matches any uniformly classified subset, regardless of the size of the subset. Even this approach works quite well, as Figure 18.12 suggests.

REGRESSION AND CLASSIFICATION WITH LINEAR MODELS

Now it is time to move on from decision trees and lists to a different hypothesis space, one that has been used for hundred of years: the class of linear functions of continuous-valued

inputs. We’ll start with the simplest case: regression with a univariate linear function, otherwise known as “fitting a straight line.” Section 18.6.2 covers the multivariate case. Sections 18.6.3 and 18.6.4 show how to turn linear functions into classifiers by applying hard and soft thresholds.

Univariate linear regression

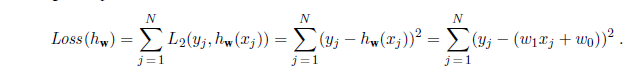

A univariate linear function (a straight line) with input x and output y has the form y = w~1~x+ w~0~, where w~0~ and w~1~ are real-valued coefficients to be learned. We use the letter w because we think of the coefficients as weights; the value of y is changed by changing the relative weight of one term or another. We’ll define w to be the vector [w~0~, w~1~], and define

h~w~(x)= w~1~x + w~0~ .

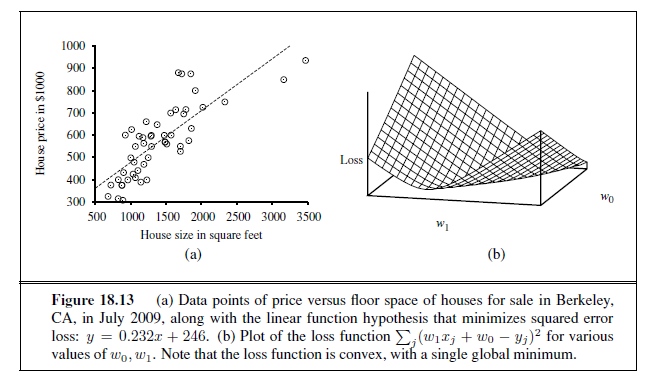

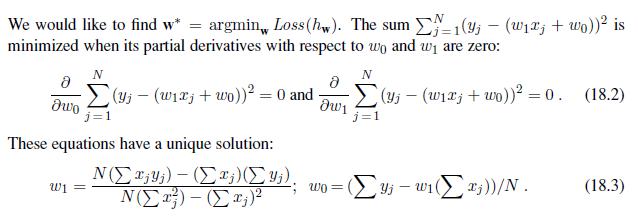

Figure 18.13(a) shows an example of a training set of n points in the x, y plane, each point representing the size in square feet and the price of a house offered for sale. The task of finding the h~w~ that best fits these data is called linear regression. To fit a line to the data, all we have to do is find the values of the weights [w~0~, w1] that minimize the empirical loss. It is traditional (going back to Gauss3) to use the squared loss function, L~2~, summed over all the training examples:

3 Gauss showed that if the y~j~ values have normally distributed noise, then the most likely values of w~1~ and w~0~ are obtained by minimizing the sum of the squares of the errors.

For the example in Figure 18.13(a), the solution is w1 = 0.232, w~0~ = 246, and the line with those weights is shown as a dashed line in the figure.

Many forms of learning involve adjusting weights to minimize a loss, so it helps to have a mental picture of what’s going on in weight space—the space defined by all possible settings of the weights. For univariate linear regression, the weight space defined by w~0~ and w1 is two-dimensional, so we can graph the loss as a function of w~0~ and w1 in a 3D plot (see Figure 18.13(b)). We see that the loss function is convex, as defined on page 133; this is true for every linear regression problem with an L~2~ loss function, and implies that there are no local minima. In some sense that’s the end of the story for linear models; if we need to fit lines to data, we apply Equation (18.3).4

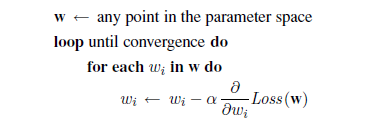

To go beyond linear models, we will need to face the fact that the equations defining minimum loss (as in Equation (18.2)) will often have no closed-form solution. Instead, we will face a general optimization search problem in a continuous weight space. As indicated in Section 4.2 (page 129), such problems can be addressed by a hill-climbing algorithm that follows the gradient of the function to be optimized. In this case, because we are trying to minimize the loss, we will use gradient descent. We choose any starting point in weight space—here, a point in the (w~0~, w1) plane—and then move to a neighboring point that is downhill, repeating until we converge on the minimum possible loss:

The parameter α, which we called the step size in Section 4.2, is usually called the learning rate when we are trying to minimize loss in a learning problem. It can be a fixed constant, or it can decay over time as the learning process proceeds.

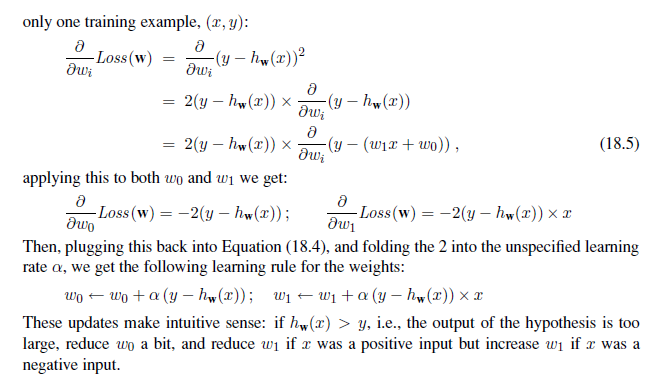

For univariate regression, the loss function is a quadratic function, so the partial derivative will be a linear function. (The only calculus you need to know is that ∂/∂x x^2^=2x and∂/∂x x= 1.) Let’s first work out the partial derivatives—the slopes—in the simplified case of

4 With some caveats: the L~2~ loss function is appropriate when there is normally-distributed noise that is independent of x; all results rely on the stationarity assumption; etc.

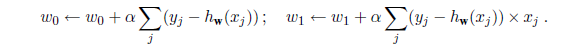

The preceding equations cover one training example. For N training examples, we want to minimize the sum of the individual losses for each example. The derivative of a sum is the sum of the derivatives, so we have:

These updates constitute the batch gradient descent learning rule for univariate linear regression. Convergence to the unique global minimum is guaranteed (as long as we pick α small enough) but may be very slow: we have to cycle through all the training data for every step, and there may be many steps.

There is another possibility, called stochastic gradient descent, where we consider only a single training point at a time, taking a step after each one using Equation (18.5). Stochastic gradient descent can be used in an online setting, where new data are coming in one at a time, or offline, where we cycle through the same data as many times as is necessary, taking a step after considering each single example. It is often faster than batch gradient descent. With a fixed learning rate α, however, it does not guarantee convergence; it can oscillate around the minimum without settling down. In some cases, as we see later, a schedule of decreasing learning rates (as in simulated annealing) does guarantee convergence.

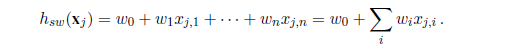

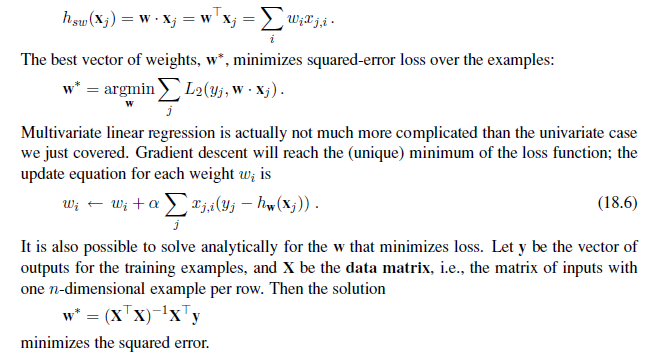

Multivariate linear regression

We can easily extend to multivariate linear regression problems, in which each example x~j~ is an n-element vector.5 Our hypothesis space is the set of functions of the form

5 The reader may wish to consult Appendix A for a brief summary of linear algebra.

The w~0~ term, the intercept, stands out as different from the others. We can fix that by inventing a dummy input attribute, x~j,0~, which is defined as always equal to 1. Then h is simply the dot product of the weights and the input vector (or equivalently, the matrix product of the transpose of the weights and the input vector):

With univariate linear regression we didn’t have to worry about overfitting. But with multivariate linear regression in high-dimensional spaces it is possible that some dimension that is actually irrelevant appears by chance to be useful, resulting in overfitting.

Thus, it is common to use regularization on multivariate linear functions to avoid overfitting. Recall that with regularization we minimize the total cost of a hypothesis, counting both the empirical loss and the complexity of the hypothesis:

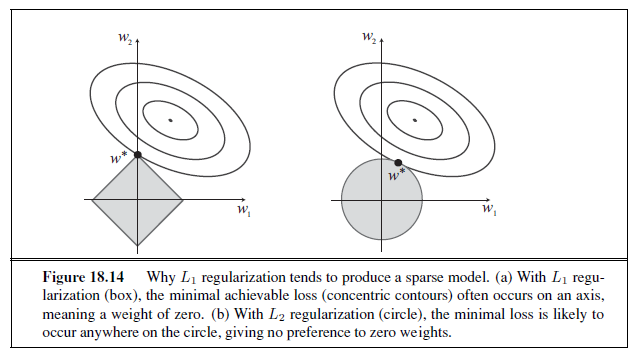

As with loss functions,6 with q =1 we have L~1~ regularization, which minimizes the sum of the absolute values; with q =2, L~2~ regularization minimizes the sum of squares. Which regularization function should you pick? That depends on the specific problem, but L~1~ regularization has an important advantage: it tends to produce a sparse model. That is, it often sets many weights to zero, effectively declaring the corresponding attributes to be irrelevant—just as DECISION-TREE-LEARNING does (although by a different mechanism). Hypotheses that discard attributes can be easier for a human to understand, and may be less likely to overfit.

6 It is perhaps confusing that L~1~ and L~2~ are used for both loss functions and regularization functions. They need not be used in pairs: you could use L~2~ loss with L~1~ regularization, or vice versa.

Figure 18.14 gives an intuitive explanation of why L~1~ regularization leads to weights of zero, while L~2~ regularization does not. Note that minimizing Loss(w) + λComplexity(w) is equivalent to minimizing Loss(w) subject to the constraint that Complexity(w) ≤ c, for some constant c that is related to λ. Now, in Figure 18.14(a) the diamond-shaped box represents the set of points w in two-dimensional weight space that have L~1~ complexity less than c; our solution will have to be somewhere inside this box. The concentric ovals represent contours of the loss function, with the minimum loss at the center. We want to find the point in the box that is closest to the minimum; you can see from the diagram that, for an arbitrary position of the minimum and its contours, it will be common for the corner of the box to find its way closest to the minimum, just because the corners are pointy. And of course the corners are the points that have a value of zero in some dimension. In Figure 18.14(b), we’ve done the same for the L~2~ complexity measure, which represents a circle rather than a diamond. Here you can see that, in general, there is no reason for the intersection to appear on one of the axes; thus L~2~ regularization does not tend to produce zero weights. The result is that the number of examples required to find a good h is linear in the number of irrelevant features for L~2~ regularization, but only logarithmic with L~1~ regularization. Empirical evidence on many problems supports this analysis.

Another way to look at it is that L~1~ regularization takes the dimensional axes seriously, while L~2~ treats them as arbitrary. The L~2~ function is spherical, which makes it rotationally invariant: Imagine a set of points in a plane, measured by their x and y coordinates. Now imagine rotating the axes by 45o. You’d get a different set of (x′, y ′) values representing the same points. If you apply L~2~ regularization before and after rotating, you get exactly the same point as the answer (although the point would be described with the new (x′, y ′) coordinates). That is appropriate when the choice of axes really is arbitrary—when it doesn’t matter whether your two dimensions are distances north and east; or distances north-east and south-east. With L~1~ regularization you’d get a different answer, because the L~1~ function is not rotationally invariant. That is appropriate when the axes are not interchangeable; it doesn’t make sense to rotate “number of bathrooms” 45o towards “lot size.”

Linear classifiers with a hard threshold

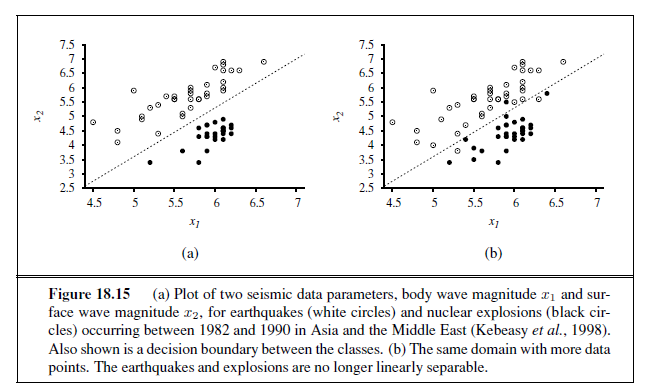

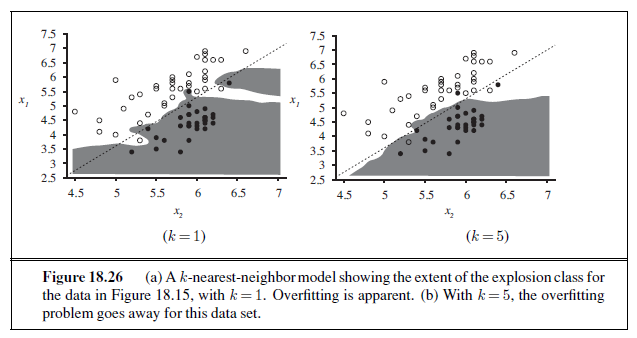

Linear functions can be used to do classification as well as regression. For example, Figure 18.15(a) shows data points of two classes: earthquakes (which are of interest to seismologists) and underground explosions (which are of interest to arms control experts). Each point is defined by two input values, x~1~ and x~2~, that refer to body and surface wave magnitudes computed from the seismic signal. Given these training data, the task of classification is to learn a hypothesis h that will take new (x~1~, x~2~) points and return either 0 for earthquakes or 1 for explosions.

A decision boundary is a line (or a surface, in higher dimensions) that separates theDECISION BOUNDARY two classes. In Figure 18.15(a), the decision boundary is a straight line. A linear decision boundary is called a linear separator and data that admit such a separator are called linearly separable. The linear separator in this case is defined by

x~2~ = 1.7x~1~ − 4.9 or − 4.9 + 1.7x~1~ − x~2~ = 0 .

The explosions, which we want to classify with value 1, are to the right of this line with higher values of x~1~ and lower values of x~2~, so they are points for which −4.9 + 1.7x~1~ − x~2~ > 0, while earthquakes have −4.9 + 1.7x~1~ − x~2~ < 0. Using the convention of a dummy input x0 =1, we can write the classification hypothesis as

h~w~(x) = 1 if w · x ≥ 0 and 0 otherwise.

Alternatively, we can think of h as the result of passing the linear function w · x through a threshold function:

h~w~(x) = Threshold (w · x) where Threshold (z)= 1 if z ≥ 0 and 0 otherwise.

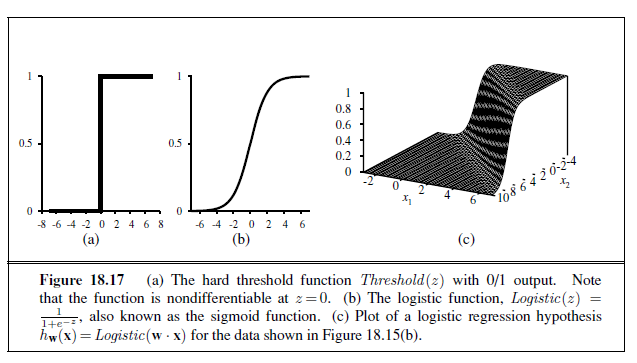

The threshold function is shown in Figure 18.17(a). Now that the hypothesis h~w~(x) has a well-defined mathematical form, we can think about choosing the weights w to minimize the loss. In Sections 18.6.1 and 18.6.2, we did this both in closed form (by setting the gradient to zero and solving for the weights) and by gradient descent in weight space. Here, we cannot do either of those things because the gradient is zero almost everywhere in weight space except at those points where w · x = 0, and at those points the gradient is undefined.

There is, however, a simple weight update rule that converges to a solution—that is, a linear separator that classifies the data perfectly–provided the data are linearly separable. For a single example (x, y), we have

w~i~ ← w~i~ + α (y − h~w~(x))× x~i~ (18.7)

which is essentially identical to the Equation (18.6), the update rule for linear regression! This rule is called the perceptron learning rule, for reasons that will become clear in Section 18.7. Because we are considering a 0/1 classification problem, however, the behavior is somewhat different. Both the true value y and the hypothesis output h~w~(x) are either 0 or 1, so there are three possibilities:

-

If the output is correct, i.e., y = h~w~(x), then the weights are not changed.

-

If y is 1 but h~w~(x) is 0, then wi is increased when the corresponding input xi is positive and decreased when xi is negative. This makes sense, because we want to make w · x bigger so that h~w~(x) outputs a 1.

-

If y is 0 but h~w~(x) is 1, then wi is decreased when the corresponding input xi is positive and increased when xi is negative. This makes sense, because we want to make w · x smaller so that h~w~(x) outputs a 0.

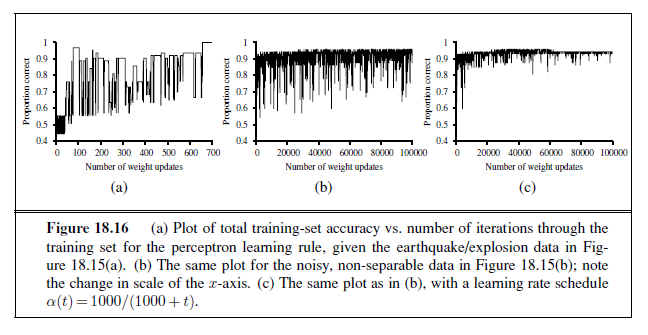

Typically the learning rule is applied one example at a time, choosing examples at random (as in stochastic gradient descent). Figure 18.16(a) shows a training curve for this learningTRAINING CURVE

rule applied to the earthquake/explosion data shown in Figure 18.15(a). A training curve measures the classifier performance on a fixed training set as the learning process proceeds on that same training set. The curve shows the update rule converging to a zero-error linear separator. The “convergence” process isn’t exactly pretty, but it always works. This particular run takes 657 steps to converge, for a data set with 63 examples, so each example is presented roughly 10 times on average. Typically, the variation across runs is very large.

We have said that the perceptron learning rule converges to a perfect linear separator when the data points are linearly separable, but what if they are not? This situation is all too common in the real world. For example, Figure 18.15(b) adds back in the data points left out by Kebeasy et al. (1998) when they plotted the data shown in Figure 18.15(a). In Figure 18.16(b), we show the perceptron learning rule failing to converge even after 10,000 steps: even though it hits the minimum-error solution (three errors) many times, the algorithm keeps changing the weights. In general, the perceptron rule may not converge to a

stable solution for fixed learning rate α, but if α decays as O(1/t) where t is the iteration number, then the rule can be shown to converge to a minimum-error solution when examples are presented in a random sequence.7 It can also be shown that finding the minimum-error solution is NP-hard, so one expects that many presentations of the examples will be required for convergence to be achieved. Figure 18.16(b) shows the training process with a learning rate schedule α(t)= 1000/(1000 + t): convergence is not perfect after 100,000 iterations, but it is much better than the fixed-α case.

Linear classification with logistic regression

We have seen that passing the output of a linear function through the threshold function creates a linear classifier; yet the hard nature of the threshold causes some problems: the hypothesis h~w~(x) is not differentiable and is in fact a discontinuous function of its inputs and its weights; this makes learning with the perceptron rule a very unpredictable adventure. Furthermore, the linear classifier always announces a completely confident prediction of 1 or 0, even for examples that are very close to the boundary; in many situations, we really need more gradated predictions.

All of these issues can be resolved to a large extent by softening the threshold function— approximating the hard threshold with a continuous, differentiable function. In Chapter 14 (page 522), we saw two functions that look like soft thresholds: the integral of the standard normal distribution (used for the probit model) and the logistic function (used for the logit model). Although the two functions are very similar in shape, the logistic function

Logistic(z) = 1/1 + e −z

has more convenient mathematical properties. The function is shown in Figure 18.17(b). With the logistic function replacing the threshold function, we now have

h~w~(x) = Logistic(w · x) = 1 / 1 + e −^w·x^ .

An example of such a hypothesis for the two-input earthquake/explosion problem is shown in Figure 18.17(c). Notice that the output, being a number between 0 and 1, can be interpreted as a probability of belonging to the class labeled 1. The hypothesis forms a soft boundary in the input space and gives a probability of 0.5 for any input at the center of the boundary region, and approaches 0 or 1 as we move away from the boundary.

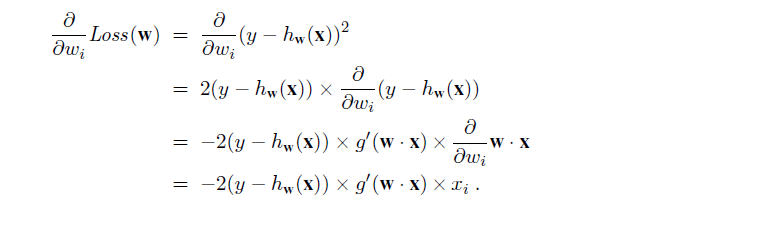

The process of fitting the weights of this model to minimize loss on a data set is called logistic regression. There is no easy closed-form solution to find the optimal value of w with this model, but the gradient descent computation is straightforward. Because our hypotheses no longer output just 0 or 1, we will use the L~2~ loss function; also, to keep the formulas readable, we’ll use g to stand for the logistic function, with g′ its derivative. For a single example (x, y), the derivation of the gradient is the same as for linear regression (Equation (18.5)) up to the point where the actual form of h is inserted. (For this derivation, we will need the chain rule: ∂g(f(x))/∂x= g′(f(x)) ∂f(x)/∂x.) We have

The derivative g ′ of the logistic function satisfies g′(z)= g(z)(1 − g(z)), so we have

g′(w · x) = g(w · x)(1− g(w · x)) = h~w~(x)(1− h~w~(x))

so the weight update for minimizing the loss is

w~i~ ← w~i~ + α (y − h~w~(x))× h~w~(x)(1− h~w~(x))× x~i~ . (18.8)

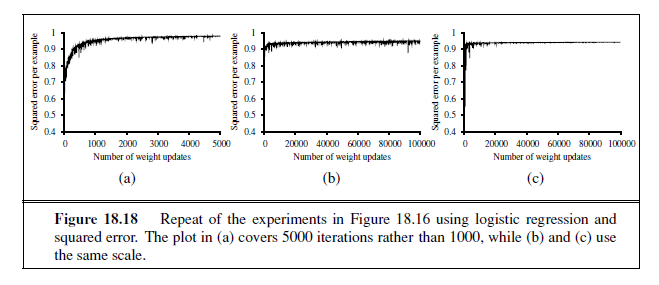

Repeating the experiments of Figure 18.16 with logistic regression instead of the linear threshold classifier, we obtain the results shown in Figure 18.18. In (a), the linearly separable case, logistic regression is somewhat slower to converge, but behaves much more predictably. In (b) and (c), where the data are noisy and nonseparable, logistic regression converges far more quickly and reliably. These advantages tend to carry over into real-world applications and logistic regression has become one of the most popular classification techniques for problems in medicine, marketing and survey analysis, credit scoring, public health, and other applications.

ARTIFICIAL NEURAL NETWORKS

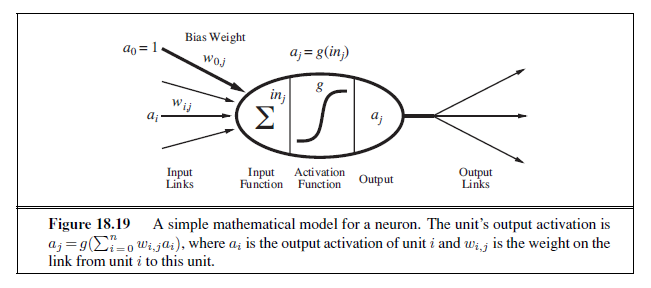

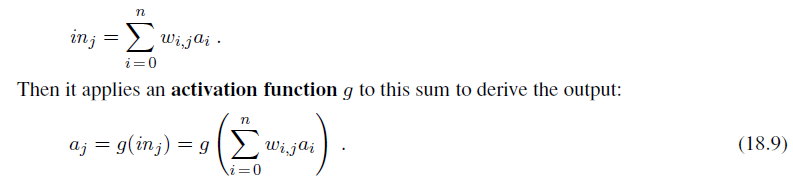

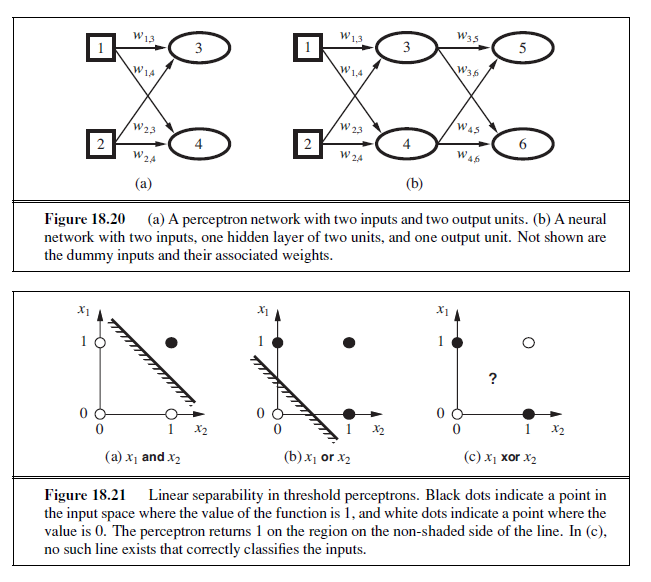

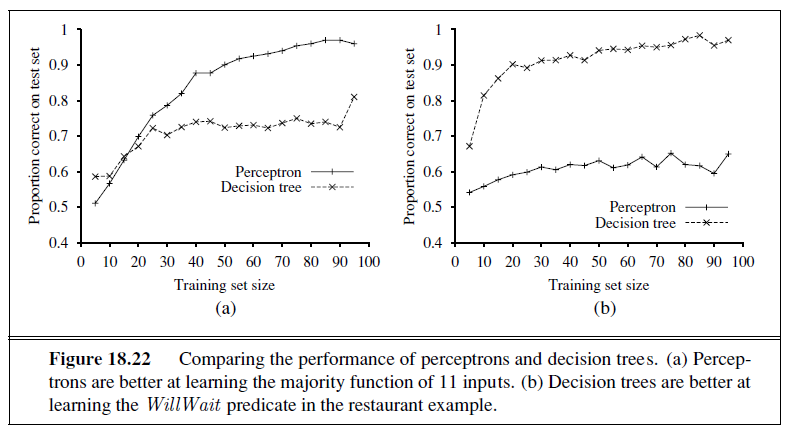

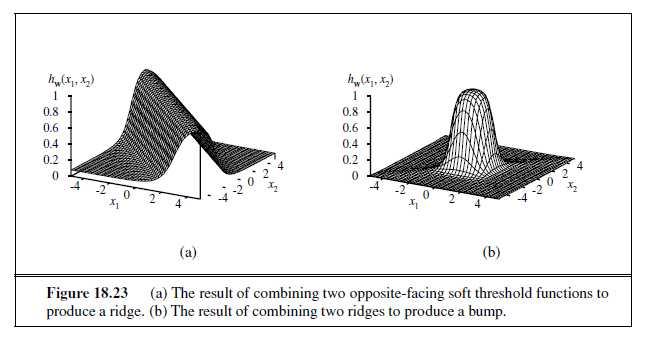

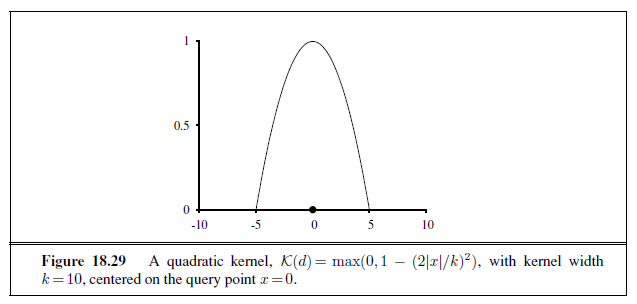

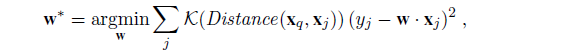

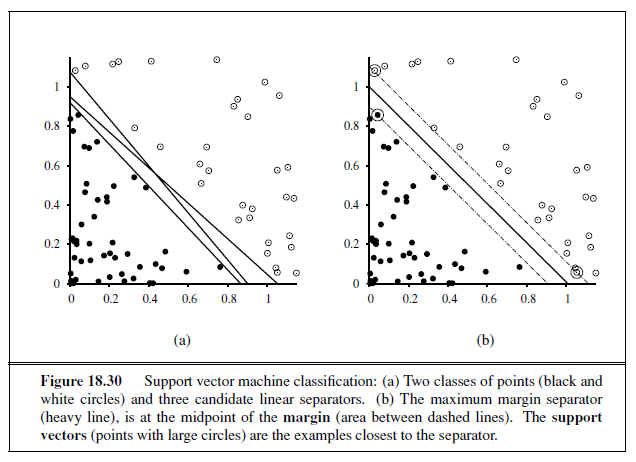

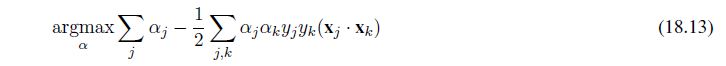

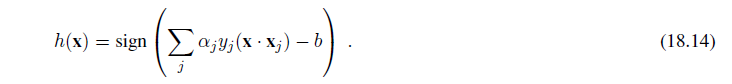

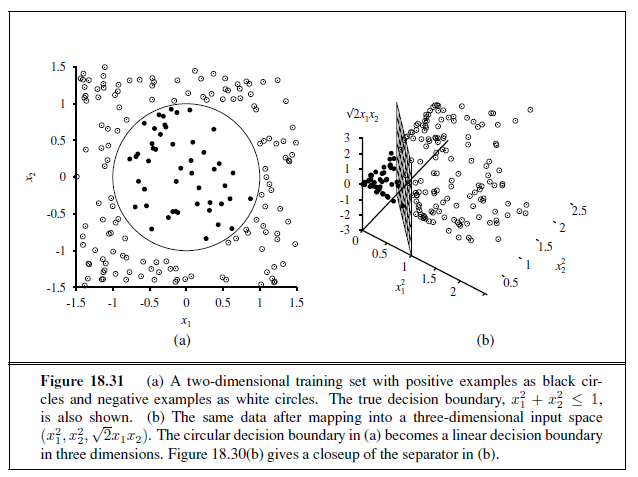

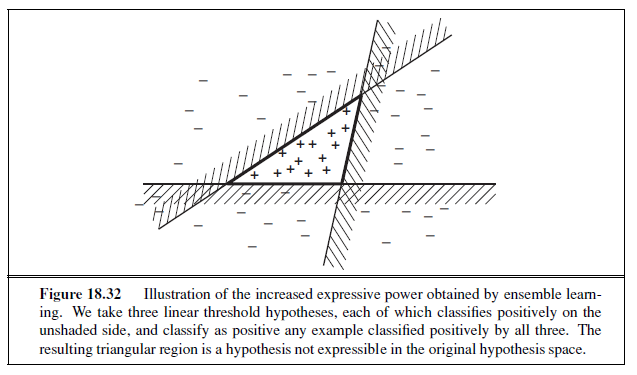

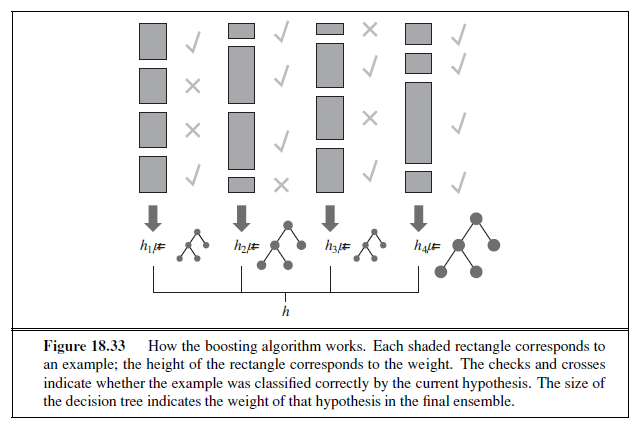

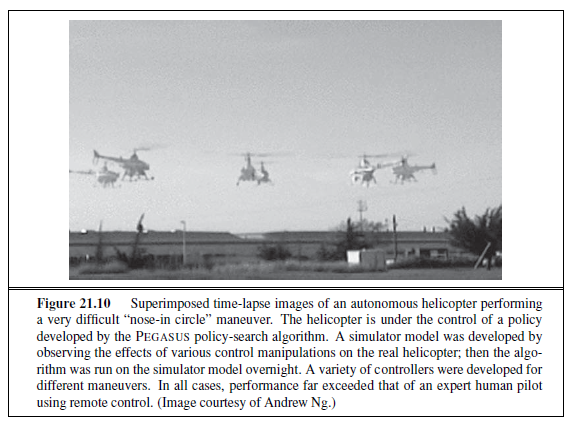

We turn now to what seems to be a somewhat unrelated topic: the brain. In fact, as we will see, the technical ideas we have discussed so far in this chapter turn out to be useful in building mathematical models of the brain’s activity; conversely, thinking about the brain has helped in extending the scope of the technical ideas.