LOGICAL AGENTS

In which we design agents that can form representations of a complex world, use a process of inference to derive new representations about the world, and use these new representations to deduce what to do.

Humans, it seems, know things; and what they know helps them do things. These are not empty statements. They make strong claims about how the intelligence of humans is achieved—not by purely reflex mechanisms but by processes of reasoning that operate on internal representations of knowledge. In AI, this approach to intelligence is embodied inknowledge-based agents.

The problem-solving agents of Chapters 3 and 4 know things, but only in a very limited, inflexible sense. For example, the transition model for the 8-puzzle—knowledge of what the actions do—is hidden inside the domain-specific code of the RESULT function. It can be used to predict the outcome of actions but not to deduce that two tiles cannot occupy the same space or that states with odd parity cannot be reached from states with even parity. The atomic representations used by problem-solving agents are also very limiting. In a partially observable environment, an agent’s only choice for representing what it knows about the current state is to list all possible concrete states—a hopeless prospect in large environments.

Chapter 6 introduced the idea of representing states as assignments of values to variables; this is a step in the right direction, enabling some parts of the agent to work in a domain-independent way and allowing for more efficient algorithms. In this chapter and those that follow, we take this step to its logical conclusion, so to speak—we develop logic as a general class of representations to support knowledge-based agents. Such agents can combine and recombine information to suit myriad purposes. Often, this process can be quite far removed from the needs of the moment—as when a mathematician proves a theorem or an astronomer calculates the earth’s life expectancy. Knowledge-based agents can accept new tasks in the form of explicitly described goals; they can achieve competence quickly by being told or learning new knowledge about the environment; and they can adapt to changes in the environment by updating the relevant knowledge.

We begin in Section 7.1 with the overall agent design. Section 7.2 introduces a simple new environment, the wumpus world, and illustrates the operation of a knowledge-based agent without going into any technical detail. Then we explain the general principles of logic in Section 7.3 and the specifics of propositional logic in Section 7.4. While less expressive than first-order logic (Chapter 8), propositional logic illustrates all the basic concepts of logic; it also comes with well-developed inference technologies, which we describe in sections 7.5 and 7.6. Finally, Section 7.7 combines the concept of knowledge-based agents with the technology of propositional logic to build some simple agents for the wumpus world.

KNOWLEDGE-BASED AGENTS

The central component of a knowledge-based agent is its knowledge base, or KB. A knowledge base is a set of sentences. (Here “sentence” is used as a technical term. It is related but not identical to the sentences of English and other natural languages.) Each sentence is expressed in a language called a knowledge representation language and represents some assertion about the world. Sometimes we dignify a sentence with the name axiom, when the sentence is taken as given without being derived from other sentences.

There must be a way to add new sentences to the knowledge base and a way to query what is known. The standard names for these operations are TELL and ASK, respectively. Both operations may involve inference—that is, deriving new sentences from old. Inference must obey the requirement that when one ASKs a question of the knowledge base, the answer should follow from what has been told (or TELLed) to the knowledge base previously. Later in this chapter, we will be more precise about the crucial word “follow.” For now, take it to mean that the inference process should not make things up as it goes along.

Figure 7.1 shows the outline of a knowledge-based agent program. Like all our agents, it takes a percept as input and returns an action. The agent maintains a knowledge base, KB , which may initially contain some background knowledge.

Each time the agent program is called, it does three things. First, it TELLs the knowledge base what it perceives. Second, it ASKs the knowledge base what action it should perform. In the process of answering this query, extensive reasoning may be done about the current state of the world, about the outcomes of possible action sequences, and so on. Third, the agent program TELLs the knowledge base which action was chosen, and the agent executes the action.

The details of the representation language are hidden inside three functions that implement the interface between the sensors and actuators on one side and the core representation and reasoning system on the other. MAKE-PERCEPT-SENTENCE constructs a sentence asserting that the agent perceived the given percept at the given time. constructs a sentence that asks what action should be done at the current time. Finally, MAKE-ACTION-SENTENCE constructs a sentence asserting that the chosen action was executed. The details of the inference mechanisms are hidden inside TELL and ASK. Later sections will reveal these details.

The agent in Figure 7.1 appears quite similar to the agents with internal state described in Chapter 2. Because of the definitions of TELL and ASK, however, the knowledge-based agent is not an arbitrary program for calculating actions. It is amenable to a description at

function KB-AGENT(percept ) returns an action persistent: KB , a knowledge base t , a counter, initially 0, indicating time

TELL(KB , MAKE-PERCEPT-SENTENCE(percept , t )) action←ASK(KB , MAKE-ACTION-QUERY(t )) TELL(KB , MAKE-ACTION-SENTENCE(action , t )) t← t + 1 return action

Figure 7.1 A generic knowledge-based agent. Given a percept, the agent adds the percept to its knowledge base, asks the knowledge base for the best action, and tells the knowledge base that it has in fact taken that action. the knowledge level, where we need specify only what the agent knows and what its goals are, in order to fix its behavior. For example, an automated taxi might have the goal of taking a passenger from San Francisco to Marin County and might know that the Golden Gate Bridge is the only link between the two locations. Then we can expect it to cross the Golden Gate Bridge because it knows that that will achieve its goal. Notice that this analysis is independent of how the taxi works at the implementation level. It doesn’t matter whether its geographical knowledge is implemented as linked lists or pixel maps, or whether it reasons by manipulating strings of symbols stored in registers or by propagating noisy signals in a network of neurons.

A knowledge-based agent can be built simply by TELLing it what it needs to know. Starting with an empty knowledge base, the agent designer can TELL sentences one by one until the agent knows how to operate in its environment. This is called the declarative approach to system building. In contrast, the procedural approach encodes desired behaviors directly as program code. In the 1970s and 1980s, advocates of the two approaches engaged in heated debates. We now understand that a successful agent often combines both declarative and procedural elements in its design, and that declarative knowledge can often be compiled into more efficient procedural code.

We can also provide a knowledge-based agent with mechanisms that allow it to learn for itself. These mechanisms, which are discussed in Chapter 18, create general knowledge about the environment from a series of percepts. A learning agent can be fully autonomous.

THE WUMPUS WORLD

In this section we describe an environment in which knowledge-based agents can show their worth. The wumpus world is a cave consisting of rooms connected by passageways. Lurking somewhere in the cave is the terrible wumpus, a beast that eats anyone who enters its room. The wumpus can be shot by an agent, but the agent has only one arrow. Some rooms contain bottomless pits that will trap anyone who wanders into these rooms (except for the wumpus, which is too big to fall in). The only mitigating feature of this bleak environment is the possibility of finding a heap of gold. Although the wumpus world is rather tame by modern computer game standards, it illustrates some important points about intelligence.

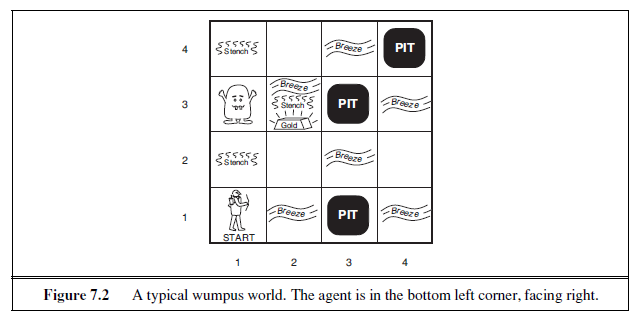

A sample wumpus world is shown in Figure 7.2. The precise definition of the task environment is given, as suggested in Section 2.3, by the PEAS description:

-

Performance measure: +1000 for climbing out of the cave with the gold, –1000 for falling into a pit or being eaten by the wumpus, –1 for each action taken and –10 for using up the arrow. The game ends either when the agent dies or when the agent climbs out of the cave.

-

Environment: A 4× 4 grid of rooms. The agent always starts in the square labeled [1,1], facing to the right. The locations of the gold and the wumpus are chosen randomly, with a uniform distribution, from the squares other than the start square. In addition, each square other than the start can be a pit, with probability 0.2.

-

Actuators: The agent can move Forward, TurnLeft by 90◦, or TurnRight by 90◦. The agent dies a miserable death if it enters a square containing a pit or a live wumpus. (It is safe, albeit smelly, to enter a square with a dead wumpus.) If an agent tries to move forward and bumps into a wall, then theagent does not move. The action Grab can be used to pick up the gold if it is in the same square as the agent. The action Shoot can be used to fire an arrow in a straight line in the direction the agent is facing. The arrow continues until it either hits (and hence kills) the wumpus or hits a wall. The agent has only one arrow, so only the first Shoot action has any effect. Finally, the action Climb can be used to climb out of the cave, but only from square [1,1].

-

Sensors: The agent has five sensors, each of which gives a single bit of information:

– In the square containing the wumpus and in the directly (not diagonally) adjacent squares, the agent will perceive a Stench.

– In the squares directly adjacent to a pit, the agent will perceive a Breeze. – In the square where the gold is, the agent will perceive a Glitter. – When an agent walks into a wall, it will perceive a Bump. – When the wumpus is killed, it emits a woeful Scream that can be perceived anywhere in the cave.

The percepts will be given to the agent program in the form of a list of five symbols; for example, if there is a stench and a breeze, but no glitter, bump, or scream, the agent program will get [Stench,Breeze ,None,None,None ].

We can characterize the wumpus environment along the various dimensions given in Chapter 2. Clearly, it is discrete, static, and single-agent. (The wumpus doesn’t move, fortunately.) It is sequential, because rewards may come only after many actions are taken. It is partially observable, because some aspects of the state are not directly perceivable: the agent’s location, the wumpus’s state of health, and the availability of an arrow. As for the locations of the pits and the wumpus: we could treat them as unobserved parts of the state that happen to be immutable—in which case, the transition model for the environment is completely

known; or we could say that the transition model itself is unknown because the agent doesn’t know which Forward actions are fatal—in which case, discovering the locations of pits and wumpus completes the agent’s knowledge of the transition model.

For an agent in the environment, the main challenge is its initial ignorance of the configuration of the environment; overcoming this ignorance seems to require logical reasoning. In most instances of the wumpus world, it is possible for the agent to retrieve the gold safely. Occasionally, the agent must choose between going home empty-handed and risking death to find the gold. About 21% of the environments are utterly unfair, because the gold is in a pit or surrounded by pits.

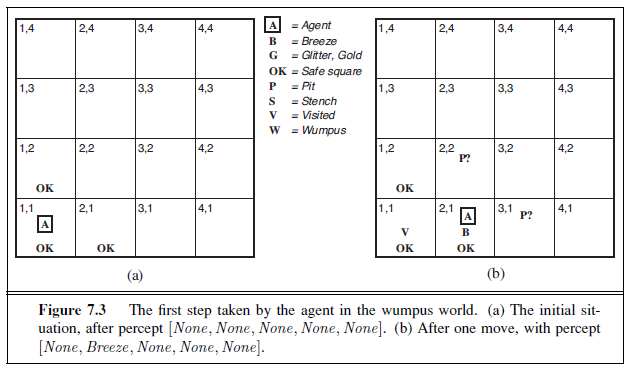

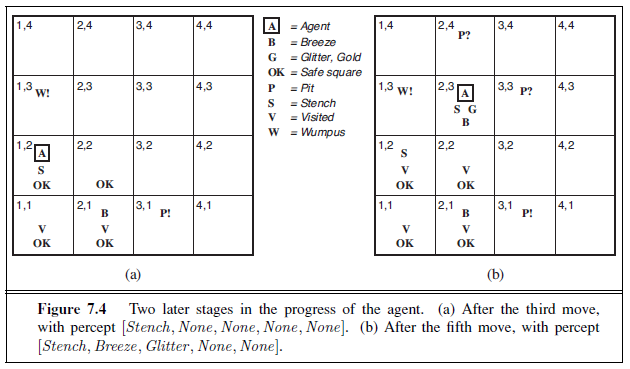

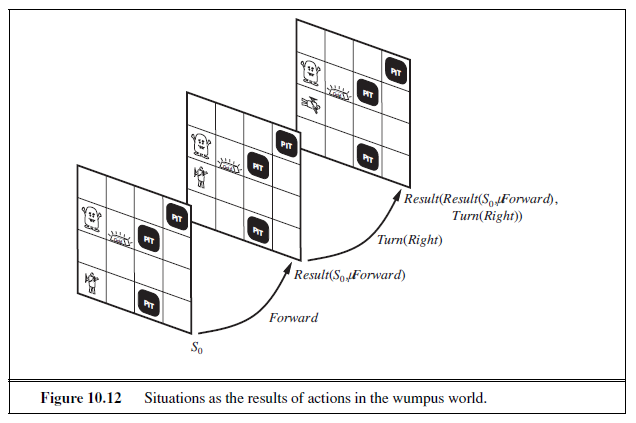

Let us watch a knowledge-based wumpus agent exploring the environment shown in Figure 7.2. We use an informal knowledge representation language consisting of writing down symbols in a grid (as in Figures 7.3 and 7.4).

The agent’s initial knowledge base contains the rules of the environment, as described previously; in particular, it knows that it is in [1,1] and that [1,1] is a safe square; we denote that with an “A” and “OK,” respectively, in square [1,1].

The first percept is [None,None,None,None ,None], from which the agent can conclude that its neighboring squares, [1,2] and [2,1], are free of dangers—they are OK. Figure 7.3(a) shows the agent’s state of knowledge at this point.

A cautious agent will move only into a square that it knows to be OK. Let us suppose the agent decides to move forward to [2,1]. The agent perceives a breeze (denoted by “B”) in [2,1], so there must be a pit in a neighboring square. The pit cannot be in [1,1], by the rules of the game, so there must be a pit in [2,2] or [3,1] or both. The notation “P?” in Figure 7.3(b) indicates a possible pit in those squares. At this point, there is only one known square that is OK and that has not yet been visited. So the prudent agent will turn around, go back to [1,1], and then proceed to [1,2].

The agent perceives a stench in [1,2], resulting in the state of knowledge shown in Figure 7.4(a). The stench in [1,2] means that there must be a wumpus nearby. But the

wumpus cannot be in [1,1], by the rules of the game, and it cannot be in [2,2] (or the agent would have detected a stench when it was in [2,1]). Therefore, the agent can infer that the wumpus is in [1,3]. The notation W! indicates this inference. Moreover, the lack of a breeze in [1,2] implies that there is no pit in [2,2]. Yet the agent has already inferred that there must be a pit in either [2,2] or [3,1], so this means it must be in [3,1]. This is a fairly difficult inference, because it combines knowledge gained at different times in different places and relies on the lack of a percept to make one crucial step.

The agent has now proved to itself that there is neither a pit nor a wumpus in [2,2], so it is OK to move there. We do not show the agent’s state of knowledge at [2,2]; we just assume that the agent turns and moves to [2,3], giving us Figure 7.4(b). In [2,3], the agent detects a glitter, so it should grab the gold and then return home.

Note that in each case for which the agent draws a conclusion from the available information, that conclusion is guaranteed to be correct if the available information is correct. This is a fundamental property of logical reasoning. In the rest of this chapter, we describe how to build logical agents that can represent information and draw conclusions such as those described in the preceding paragraphs.

LOGIC

This section summarizes the fundamental concepts of logical representation and reasoning. These beautiful ideas are independent of any of logic’s particular forms. We therefore postpone the technical details of those forms until the next section, using instead the familiar example of ordinary arithmetic.

In Section 7.1, we said that knowledge bases consist of sentences. These sentences are expressed according to the syntax of the representation language, which specifies all the sentences that are well formed. The notion of syntax is clear enough in ordinary arithmetic: “x + y = 4” is a well-formed sentence, whereas “x4y+ =” is not.

A logic must also define the semantics or meaning of sentences. The semantics definesSEMANTICS

the truth of each sentence with respect to each possible world. For example, the semanticsTRUTH

POSSIBLE WORLD for arithmetic specifies that the sentence “x + y = 4” is true in a world where x is 2 and y

is 2, but false in a world where x is 1 and y is 1. In standard logics, every sentence must be either true or false in each possible world—there is no “in between.”1

When we need to be precise, we use the term model in place of “possible world.”Where as possible worlds might be thought of as (potentially) real environments that the agent might or might not be in, models are mathematical abstractions, each of which simply fixes the truth or falsehood of every relevant sentence. Informally, we may think of a possible world as, for example, having x men and y women sitting at a table playing bridge, and the sentence x + y = 4 is true when there are four people in total. Formally, the possible models are just all possible assignments of real numbers to the variables x and y. Each such assignment fixes the truth of any sentence of arithmetic whose variables are x and y. If a sentence α is true in model m, we say that m satisfies α or sometimes m is a model of α. We use the notation M(α) to mean the set of all models of α.

Now that we have a notion of truth, we are ready to talk about logical reasoning. This involves the relation of logical entailment between sentences—the idea that a sentence follows logically from another sentence. In mathematical notation, we write

α |= β

1 Fuzzy logic, discussed in Chapter 14, allows for degrees of truth.

to mean that the sentence α entails the sentence β. The formal definition of entailment is this: α |= β if and only if, in every model in which α is true, β is also true. Using the notation just introduced, we can write

α |= β if and only if M(α) ⊆ M(β) .

(Note the direction of the ⊆ here: if α |= β, then α is a stronger assertion than β: it rules out more possible worlds.) The relation of entailment is familiar from arithmetic; we are happy with the idea that the sentence x = 0 entails the sentence x^y^ = 0. Obviously, in any model where x is zero, it is the case that x^y^ is zero (regardless of the value of y).

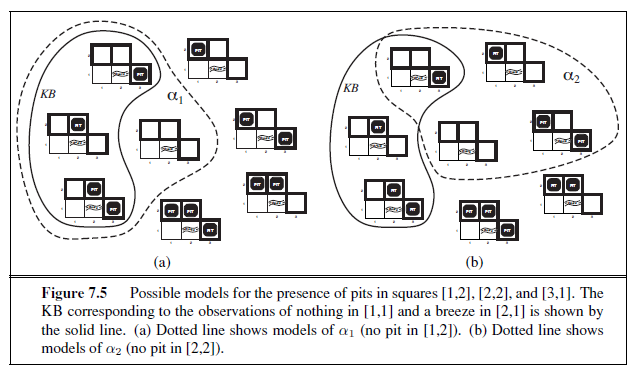

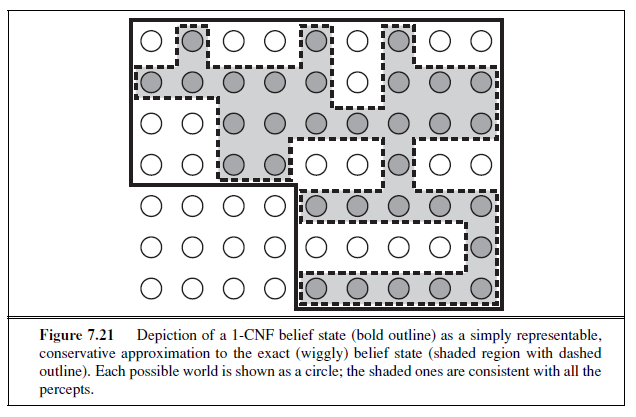

We can apply the same kind of analysis to the wumpus-world reasoning example given in the preceding section. Consider the situation in Figure 7.3(b): the agent has detected nothing in [1,1] and a breeze in [2,1]. These percepts, combined with the agent’s knowledge of the rules of the wumpus world, constitute the KB. The agent is interested (among other things) in whether the adjacent squares [1,2], [2,2], and [3,1] contain pits. Each of the three squares might or might not contain a pit, so (for the purposes of this example) there are 23 =8

possible models. These eight models are shown in Figure 7.5.2

The KB can be thought of as a set of sentences or as a single sentence that asserts all the individual sentences. The KB is false in models that contradict what the agent knows— for example, the KB is false in any model in which [1,2] contains a pit, because there is no breeze in [1,1]. There are in fact just three models in which the KB is true, and these are

2 Although the figure shows the models as partial wumpus worlds, they are really nothing more than assignments of true and false to the sentences “there is a pit in [1,2]” etc. Models, in the mathematical sense, do not need to have ’orrible ’airy wumpuses in them.

shown surrounded by a solid line in Figure 7.5. Now let us consider two possible conclusions:

α1 = “There is no pit in [1,2].” α2 = “There is no pit in [2,2].”

We have surrounded the models of α1 and α2 with dotted lines in Figures 7.5(a) and 7.5(b), respectively. By inspection, we see the following:

in every model in which KB is true, α1 is also true.

Hence, KB |= α1: there is no pit in [1,2]. We can also see that

in some models in which KB is true, α2 is false.

Hence, KB |≠ α2: the agent cannot conclude that there is no pit in [2,2]. (Nor can it conclude that there is a pit in [2,2].)^3^

The preceding example not only illustrates entailment but also shows how the definition of entailment can be applied to derive conclusions—that is, to carry out logical inference. The inference algorithm illustrated in Figure 7.5 is called model checking, because it enumerates all possible models to check that α is true in all models in which KB is true, that is, that M(KB) ⊆ M(α).

In understanding entailment and inference, it might help to think of the set of all consequences of KB as a haystack and of α as a needle. Entailment is like the needle being in the haystack; inference is like finding it. This distinction is embodied in some formal notation: if an inference algorithm i can derive α from KB , we write

KB |-~i~ α ,

which is pronounced “α is derived from KB by i” or “i derives α from KB .” An inference algorithm that derives only entailed sentences is called sound or truthpreserving. Soundness is a highly desirable property. An unsound inference procedure essentially makes things up as it goes along—it announces the discovery of nonexistent needles. It is easy to see that model checking, when it is applicable,4 is a sound procedure.

The property of completeness is also desirable: an inference algorithm is complete if it can derive any sentence that is entailed. For real haystacks, which are finite in extent, it seems obvious that a systematic examination can always decide whether the needle is in the haystack. For many knowledge bases, however, the haystack of consequences is infinite, and completeness becomes an important issue.5 Fortunately, there are complete inference procedures for logics that are sufficiently expressive to handle many knowledge bases.

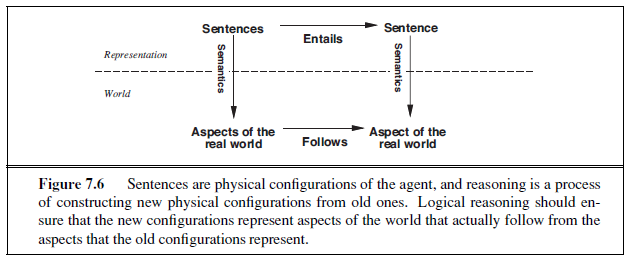

We have described a reasoning process whose conclusions are guaranteed to be true in any world in which the premises are true; in particular, if KB is true in the real world, then any sentence α derived from KB by a sound inference procedure is also true in the real world. So, while an inference process operates on “syntax”—internal physical configurations such as bits in registers or patterns of electrical blips in brains—the process corresponds

3 The agent can calculate the probability that there is a pit in [2,2]; Chapter 13 shows how. 4 Model checking works if the space of models is finite—for example, in wumpus worlds of fixed size. For arithmetic, on the other hand, the space of models is infinite: even if we restrict ourselves to the integers, there are infinitely many pairs of values for x and y in the sentence x + y = 4. 5 Compare with the case of infinite search spaces in Chapter 3, where depth-first search is not complete.

to the real-world relationship whereby some aspect of the real world is the case6 by virtue of other aspects of the real world being the case. This correspondence between world and representation is illustrated in Figure 7.6.

The final issue to consider is grounding—the connection between logical reasoning processes and the real environment in which the agent exists. In particular, how do we know that KB is true in the real world? (After all, KB is just “syntax” inside the agent’s head.) This is a philosophical question about which many, many books have been written. (See Chapter 26.) A simple answer is that the agent’s sensors create the connection. For example, our wumpus-world agent has a smell sensor. The agent program creates a suitable sentence whenever there is a smell. Then, whenever that sentence is in the knowledge base, it is true in the real world. Thus, the meaning and truth of percept sentences are defined by the processes of sensing and sentence construction that produce them. What about the rest of the agent’s knowledge, such as its belief that wumpuses cause smells in adjacent squares? This is not a direct representation of a single percept, but a general rule—derived, perhaps, from perceptual experience but not identical to a statement of that experience. General rules like this are produced by a sentence construction process called learning, which is the subject of Part V. Learning is fallible. It could be the case that wumpuses cause smells except on February 29 in leap years, which is when they take their baths. Thus, KB may not be true in the real world, but with good learning procedures, there is reason for optimism.

PROPOSITIONAL LOGIC: A VERY SIMPLE LOGIC

We now present a simple but powerful logic called propositional logic. We cover the syntax of propositional logic and its semantics—the way in which the truth of sentences is determined. Then we look at entailment—the relation between a sentence and another sentence that follows from it—and see how this leads to a simple algorithm for logical inference. Everything takes place, of course, in the wumpus world.

6 As Wittgenstein (1922) put it in his famous Tractatus: “The world is everything that is the case.”

Syntax

The syntax of propositional logic defines the allowable sentences. The atomic sentences consist of a single proposition symbol. Each such symbol stands for a proposition that can be true or false. We use symbols that start with an uppercase letter and may contain other letters or subscripts, for example: P , Q, R, W~1,3~ and North . The names are arbitrary but are often chosen to have some mnemonic value—we use W~1,3~ to stand for the proposition that the wumpus is in [1,3]. (Remember that symbols such as W~1,3~ are atomic, i.e., W , 1, and 3 are not meaningful parts of the symbol.) There are two proposition symbols with fixed meanings: True is the always-true proposition and False is the always-false proposition. Complex sentences are constructed from simpler sentences, using parentheses and logical connectives. There are five connectives in common use:

-

¬ (not). A sentence such as ¬W~1,3~ is called the negation of W~1,3~. A literal is either an atomic sentence (a positive literal) or a negated atomic sentence (a negative literal).

-

∧ (and). A sentence whose main connective is ∧, such as W~1,3~ ∧ P~3,1~, is called a conjunction; its parts are the conjuncts. (The ∧ looks like an “A” for “And.”)

-

∨ (or). A sentence using ∨, such as (W~1,3~∧P~3,1~)∨W~2,2~, is a disjunction of the disjuncts (W~1,3~ ∧ P~3,1~) and W~2,2~. (Historically, the ∨ comes from the Latin “vel,” which means “or.” For most people, it is easier to remember ∨ as an upside-down ∧.)

-

⇒ (implies). A sentence such as (W~1,3~∧P~3,1~) ⇒ ¬W~2,2~ is called an implication (or conditional). Its premise or antecedent is (W~1,3~∧P~3,1~), and its conclusion or consequent is ¬W~2,2~. Implications are also known as rules or if–then statements. The implication RULES symbol is sometimes written in other books as ⊃ or →.

⇔ (if and only if). The sentence W~1,3~ ⇔ ¬W~2,2~ is a biconditional. Some other books write this as ≡.

Sentence → AtomicSentence | ComplexSentence

AtomicSentence → True | False | P | Q | R | . . .

ComplexSentence → ( Sentence ) | [ Sentence ]

| ¬ Sentence

| Sentence ∧ Sentence

| Sentence ∨ Sentence

| Sentence ⇒ Sentence

| Sentence ⇔ Sentence

OPERATOR PRECEDENCE : ¬,∧,∨,⇒,⇔

Figure 7.7 A BNF (Backus–Naur Form) grammar of sentences in propositional logic, along with operator precedences, from highest to lowest.

Figure 7.7 gives a formal grammar of propositional logic; see page 1060 if you are not familiar with the BNF notation. The BNF grammar by itself is ambiguous; a sentence with several operators can be parsed by the grammar in multiple ways. To eliminate the ambiguity we define a precedence for each operator. The “not” operator (¬) has the highest precedence, which means that in the sentence ¬A ∧ B the ¬ binds most tightly, giving us the equivalent of (¬A)∧B rather than ¬(A∧B). (The notation for ordinary arithmetic is the same: −2+4 is 2, not –6.) When in doubt, use parentheses to make sure of the right interpretation. Square brackets mean the same thing as parentheses; the choice of square brackets or parentheses is solely to make it easier for a human to read a sentence.

Semantics

Having specified the syntax of propositional logic, we now specify its semantics. The semantics defines the rules for determining the truth of a sentence with respect to a particular model. In propositional logic, a model simply fixes the truth value—true or false—for every proposition symbol. For example, if the sentences in the knowledge base make use of the proposition symbols P~1,2~, P~2,2~, and P~3,1~, then one possible model is

M~1~ = {P~1,2~ = false, P~2,2~ = false, P~3,1~ = true} .

With three proposition symbols, there are 23 = 8 possible models—exactly those depicted in Figure 7.5. Notice, however, that the models are purely mathematical objects with no necessary connection to wumpus worlds. P~1,2~ is just a symbol; it might mean “there is a pit in [1,2]” or “I’m in Paris today and tomorrow.”

The semantics for propositional logic must specify how to compute the truth value of any sentence, given a model. This is done recursively. All sentences are constructed from atomic sentences and the five connectives; therefore, we need to specify how to compute the truth of atomic sentences and how to compute the truth of sentences formed with each of the five connectives. Atomic sentences are easy:

-

True is true in every model and False is false in every model.

-

The truth value of every other proposition symbol must be specified directly in the model. For example, in the model M~1~ given earlier, P~1,2~ is false.

For complex sentences, we have five rules, which hold for any subsentences P and Q in any model m (here “iff” means “if and only if”):

-

¬P is true iff P is false in m.

-

P ∧Q is true iff both P and Q are true in m.

-

P ∨Q is true iff either P or Q is true in m.

-

P ⇒ Q is true unless P is true and Q is false in m.

-

P ⇔ Q is true iff P and Q are both true or both false in m.

The rules can also be expressed with truth tables that specify the truth value of a complex sentence for each possible assignment of truth values to its components. Truth tables for the five connectives are given in Figure 7.8. From these tables, the truth value of any sentence s can be computed with respect to any model m by a simple recursive evaluation. For example,

| P | Q | ¬P | P ∧Q | P ∨Q | P ⇒ Q | P ⇔ Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| false | false | true | false | false | true | true |

| false | true | true | false | true | true | false |

| true | false | false | false | true | false | false |

| true | true | false | true | true | true | true |

Figure 7.8 Truth tables for the five logical connectives. To use the table to compute, for example, the value of P ∨Q when P is true and Q is false, first look on the left for the row where P is true and Q is false (the third row). Then look in that row under the P ∨Q column to see the result: true.

the sentence ¬P~1,2~ ∧ (P~2,2~ ∨ P~3,1~), evaluated in M~1~, gives true ∧ (false ∨ true)= true ∧

true = true . Exercise 7.3 asks you to write the algorithm PL-TRUE?(s, m), which computes the truth value of a propositional logic sentence s in a model m.

The truth tables for “and,” “or,” and “not” are in close accord with our intuitions about the English words. The main point of possible confusion is that P ∨Q is true when P is true or Q is true or both. A different connective, called “exclusive or” (“xor” for short), yields false when both disjuncts are true.7 There is no consensus on the symbol for exclusive or; some choices are ∨̇ or ≠ or ⊕.

The truth table for ⇒ may not quite fit one’s intuitive understanding of “P implies Q” or “if P then Q.” For one thing, propositional logic does not require any relation of causation or relevance between P and Q. The sentence “5 is odd implies Tokyo is the capital of Japan” is a true sentence of propositional logic (under the normal interpretation), even though it is a decidedly odd sentence of English. Another point of confusion is that any implication is true whenever its antecedent is false. For example, “5 is even implies Sam is smart” is true, regardless of whether Sam is smart. This seems bizarre, but it makes sense if you think of “P ⇒ Q” as saying, “If P is true, then I am claiming that Q is true. Otherwise I am making no claim.” The only way for this sentence to be false is if P is true but Q is false.

The biconditional, P ⇔ Q, is true whenever both P ⇒ Q and Q ⇒ P are true. In English, this is often written as “P if and only if Q.” Many of the rules of the wumpus world are best written using ⇔. For example, a square is breezy if a neighboring square has a pit, and a square is breezy only if a neighboring square has a pit. So we need a biconditional,

B~1,1~ ⇔ (P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) ,

where B~1,1~ means that there is a breeze in [1,1].

A simple knowledge base

Now that we have defined the semantics for propositional logic, we can construct a knowledge base for the wumpus world. We focus first on the immutable aspects of the wumpus world, leaving the mutable aspects for a later section. For now, we need the following symbols for each [x, y] location:

7 Latin has a separate word, aut, for exclusive or.

P~x,y~ is true if there is a pit in [x, y]. W~x,y~ is true if there is a wumpus in [x, y], dead or alive. B~x,y~ is true if the agent perceives a breeze in [x, y]. S~x,y~ is true if the agent perceives a stench in [x, y].

The sentences we write will suffice to derive ¬P~1,2~ (there is no pit in [1,2]), as was done informally in Section 7.3. We label each sentence Ri so that we can refer to them:

- There is no pit in [1,1]:

R~1~ : ¬P~1,1~ .

- A square is breezy if and only if there is a pit in a neighboring square. This has to be stated for each square; for now, we include just the relevant squares:

R~2~ : B~1,1~ ⇔ (P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) .

R~3~ : B~2,1~ ⇔ (P~1,1~ ∨ P~2,2~ ∨ P~3,1~) .

- The preceding sentences are true in all wumpus worlds. Now we include the breeze percepts for the first two squares visited in the specific world the agent is in, leading up to the situation in Figure 7.3(b).

R~4~ : ¬B~1,1~ .

R~5~ : B~2,1~ .

A simple inference procedure

Our goal now is to decide whether KB |= α for some sentence α. For example, is ¬P~1,2~ entailed by our KB? Our first algorithm for inference is a model-checking approach that is a direct implementation of the definition of entailment: enumerate the models, and check that α is true in every model in which KB is true. Models are assignments of true or false to every proposition symbol. Returning to our wumpus-world example, the relevant proposi- tion symbols are B~1,1~, B~2,1~, P~1,1~, P~1,2~, P~2,1~, P~2,2~, and P~3,1~. With seven symbols, there are 27 = 128 possible models; in three of these, KB is true (Figure 7.9). In those three models, ¬P~1,2~ is true, hence there is no pit in [1,2]. On the other hand, P~2,2~ is true in two of the three models and false in one, so we cannot yet tell whether there is a pit in [2,2].

Figure 7.9 reproduces in a more precise form the reasoning illustrated in Figure 7.5. A general algorithm for deciding entailment in propositional logic is shown in Figure 7.10. Like the BACKTRACKING-SEARCH algorithm on page 215, TT-ENTAILS? performs a recursive enumeration of a finite space of assignments to symbols. The algorithm is sound because it implements directly the definition of entailment, and complete because it works for any KB and α and always terminates—there are only finitely many models to examine.

Of course, “finitely many” is not always the same as “few.” If KB and α contain n symbols in all, then there are 2^n^ models. Thus, the time complexity of the algorithm is O(2^n^). (The space complexity is only O(n) because the enumeration is depth-first.) Later in this chapter we show algorithms that are much more efficient in many cases. Unfortunately, propositional entailment is co-NP-complete (i.e., probably no easier than NP-complete—see Appendix A), so every known inference algorithm for propositional logic has a worst-case complexity that is exponential in the size of the input.

| B~1,1~ | B~2,1~ | P~1,1~ | P~1,2~ | P~2,1~ | P~2,2~ | P~3,1~ | R~1~ | R~2~ | R~3~ | R~4~ | R~5~ | KB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| false | false | false | false | false | false | false | true | true | true | true | false | false |

| false | false | false | false | false | false | true | true | true | false | true | false | false |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| false | true | false | false | false | false | false | true | true | false | true | true | false |

| false | true | false | false | false | false | true | true | true | true | true | true | true |

| false | true | false | false | false | true | false | true | true | true | true | true | true |

| false | true | false | false | false | true | true | true | true | true | true | true | true |

| false | true | false | false | true | false | false | true | false | false | true | true | false |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| true | true | true | true | true | true | true | false | true | true | false | true | false |

Figure 7.9 A truth table constructed for the knowledge base given in the text. KB is true if R~1~ through R~5~ are true, which occurs in just 3 of the 128 rows (the ones underlined in the right-hand column). In all 3 rows, P~1,2~ is false, so there is no pit in [1,2]. On the other hand, there might (or might not) be a pit in [2,2].

function TT-ENTAILS?(KB , α) returns true or false

inputs: KB , the knowledge base, a sentence in propositional logic α, the query, a sentence in propositional logic

symbols← a list of the proposition symbols in KB and α return TT-CHECK-ALL(KB , α, symbols ,{ })

function TT-CHECK-ALL(KB , α, symbols ,model ) returns true or false

if EMPTY?(symbols) then if PL-TRUE?(KB ,model ) then return PL-TRUE?(α,model ) else return true // when KB is false, always return true

else do P ← FIRST(symbols) rest←REST(symbols) return (TT-CHECK-ALL(KB , α, rest ,model ∪ {P = true}) and TT-CHECK-ALL(KB , α, rest ,model ∪ {P = false }))

Figure 7.10 A truth-table enumeration algorithm for deciding propositional entailment. (TT stands for truth table.) PL-TRUE? returns true if a sentence holds within a model. The variable model represents a partial model—an assignment to some of the symbols. The key- word “and” is used here as a logical operation on its two arguments, returning true or false .

(α ∧ β) ≡ (β ∧ α) commutativity of ∧ (α ∨ β) ≡ (β ∨ α) commutativity of ∨ ((α ∧ β) ∧ γ) ≡ (α ∧ (β ∧ γ)) associativity of ∧ ((α ∨ β) ∨ γ) ≡ (α ∨ (β ∨ γ)) associativity of ∨ ¬(¬α) ≡ α double-negation elimination (α ⇒ β) ≡ (¬β ⇒ ¬α) contraposition (α ⇒ β) ≡ (¬α ∨ β) implication elimination (α ⇔ β) ≡ ((α ⇒ β) ∧ (β ⇒ α)) biconditional elimination ¬(α ∧ β) ≡ (¬α ∨ ¬β) De Morgan ¬(α ∨ β) ≡ (¬α ∧ ¬β) De Morgan (α ∧ (β ∨ γ)) ≡ ((α ∧ β) ∨ (α ∧ γ)) distributivity of ∧ over ∨ (α ∨ (β ∧ γ)) ≡ ((α ∨ β) ∧ (α ∨ γ)) distributivity of ∨ over ∧

Figure 7.11 Standard logical equivalences. The symbols α, β, and γ stand for arbitrary sentences of propositional logic.

PROPOSITIONAL THEOREM PROVING

So far, we have shown how to determine entailment by model checking: enumerating models and showing that the sentence must hold in all models. In this section, we show how entailment can be done by theorem proving applying rules of inference directly to the sentences in our knowledge base to construct a proof of the desired sentence without consulting models. If the number of models is large but the length of the proof is short, then theorem proving can be more efficient than model checking.

Before we plunge into the details of theorem-proving algorithms, we will need some additional concepts related to entailment. The first concept is logical equivalence: two sentences α and β are logically equivalent if they are true in the same set of models. We write this as α ≡ β. For example, we can easily show (using truth tables) that P ∧ Q and Q ∧ P are logically equivalent; other equivalences are shown in Figure 7.11. These equivalences play much the same role in logic as arithmetic identities do in ordinary mathematics. An alternative definition of equivalence is as follows: any two sentences α and β are equivalent only if each of them entails the other:

α ≡ β if and only if α |= β and β |= α .

The second concept we will need is validity. A sentence is valid if it is true in all models. For example, the sentence P ∨¬P is valid. Valid sentences are also known as tautologies—they are necessarily true. Because the sentence True is true in all models, every valid sentence is logically equivalent to True . What good are valid sentences? From our definition of entailment, we can derive the deduction theorem, which was known to the ancient Greeks:

For any sentences α and β_,_ α |= β if and only if the sentence (α ⇒ β) is valid.

(Exercise 7.5 asks for a proof.) Hence, we can decide if α |= β by checking that (α ⇒ β) is true in every model—which is essentially what the inference algorithm in Figure 7.10 does or by proving that (α ⇒ β) is equivalent to True . Conversely, the deduction theorem states that every valid implication sentence describes a legitimate inference.

The final concept we will need is satisfiability. A sentence is satisfiable if it is true in, or satisfied by, some model. For example, the knowledge base given earlier, (R~1~ ∧ R~2~ ∧ R~3~ ∧ R~4~ ∧ R~5~), is satisfiable because there are three models in which it is true, as shown in Figure 7.9. Satisfiability can be checked by enumerating the possible models until one is found that satisfies the sentence. The problem of determining the satisfiability of sentences in propositional logic—the SAT problem—was the first problem proved to be NP-complete. Many problems in computer science are really satisfiability problems. For example, all the constraint satisfaction problems in Chapter 6 ask whether the constraints are satisfiable by some assignment.

Validity and satisfiability are of course connected: α is valid iff ¬α is unsatisfiable; contrapositively, α is satisfiable iff ¬α is not valid. We also have the following useful result:

α |= β if and only if the sentence (α ∧ ¬β) is unsatisfiable.

Proving β from α by checking the unsatisfiability of (α ∧ ¬β) corresponds exactly to the standard mathematical proof technique of reductio ad absurdum (literally, “reduction to an absurd thing”). It is also called proof by refutation or proof by contradiction. One assumes a sentence β to be false and shows that this leads to a contradiction with known axioms α. This contradiction is exactly what is meant by saying that the sentence (α ∧ ¬β) is unsatisfiable.

Inference and proofs

This section covers inference rules that can be applied to derive a proof—a chain of conclu-INFERENCE RULES

PROOF sions that leads to the desired goal. The best-known rule is called Modus Ponens (Latin for MODUS PONENS mode that affirms) and is written

α ⇒ β, α / β.

The notation means that, whenever any sentences of the form α ⇒ β and α are given, then the sentence β can be inferred. For example, if (WumpusAhead ∧WumpusAlive) ⇒ Shoot

and (WumpusAhead ∧WumpusAlive) are given, then Shoot can be inferred. Another useful inference rule is And-Elimination, which says that, from a conjunction,AND-ELIMINATION

any of the conjuncts can be inferred: α ∧ β / α.

For example, from (WumpusAhead ∧ WumpusAlive), WumpusAlive can be inferred.

By considering the possible truth values of α and β, one can show easily that Modus Ponens and And-Elimination are sound once and for all. These rules can then be used in any particular instances where they apply, generating sound inferences without the need for enumerating models.

All of the logical equivalences in Figure 7.11 can be used as inference rules. For example, the equivalence for biconditional elimination yields the two inference rules

α ⇔ β / (α ⇒ β) ∧ (β ⇒ α) and (α ⇒ β) ∧ (β ⇒ α) / α ⇔ β .

Not all inference rules work in both directions like this. For example, we cannot run Modus Ponens in the opposite direction to obtain α ⇒ β and α from β.

Let us see how these inference rules and equivalences can be used in the wumpus world. We start with the knowledge base containing R~1~ through R~5~ and show how to prove ¬P~1,2~, that is, there is no pit in [1,2]. First, we apply biconditional elimination to R~2~ to obtain

R~6~ : (B~1,1~ ⇒ (P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~)) ∧ ((P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) ⇒ B~1,1~) .

Then we apply And-Elimination to R~6~ to obtain

R~7~ : ((P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) ⇒ B~1,1~) .

Logical equivalence for contrapositives gives

R~8~ : (¬B~1,1~ ⇒ ¬(P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~)) .

Now we can apply Modus Ponens with R~8~ and the percept R~4~ (i.e., ¬B~1,1~), to obtain

R~9~ : ¬(P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) .

Finally, we apply De Morgan’s rule, giving the conclusion

R~1~0 : ¬P~1,2~ ∧ ¬P~2,1~ .

That is, neither [1,2] nor [2,1] contains a pit. We found this proof by hand, but we can apply any of the search algorithms in Chapter 3

to find a sequence of steps that constitutes a proof. We just need to define a proof problem as follows:

-

INITIAL STATE: the initial knowledge base.

-

ACTIONS: the set of actions consists of all the inference rules applied to all the sentences that match the top half of the inference rule.

-

RESULT: the result of an action is to add the sentence in the bottom half of the inference rule.

-

GOAL: the goal is a state that contains the sentence we are trying to prove.

Thus, searching for proofs is an alternative to enumerating models. In many practical cases finding a proof can be more efficient because the proof can ignore irrelevant propositions, no matter how many of them there are. For example, the proof given earlier leading to ¬P~1,2~ ∧ ¬P~2,1~ does not mention the propositions B~2,1~, P~1,1~, P~2,2~, or P~3,1~. They can be ignored because the goal proposition, P~1,2~, appears only in sentence R~2~; the other propositions in R~2~ appear only in R~4~ and R~2~; so R~1~, R~3~, and R~5~ have no bearing on the proof. The same would hold even if we added a million more sentences to the knowledge base; the simple truth-table algorithm, on the other hand, would be overwhelmed by the exponential explosion of models.

One final property of logical systems is monotonicity, which says that the set of en-MONOTONICITY

tailed sentences can only increase as information is added to the knowledge base.8 For any sentences α and β,

if KB |= α then KB ∧ β |= α .

8 Nonmonotonic logics, which violate the monotonicity property, capture a common property of human reasoning: changing one’s mind. They are discussed in Section 12.6.

For example, suppose the knowledge base contains the additional assertion β stating that there are exactly eight pits in the world. This knowledge might help the agent draw additional conclusions, but it cannot invalidate any conclusion α already inferred—such as the conclusion that there is no pit in [1,2]. Monotonicity means that inference rules can be applied whenever suitable premises are found in the knowledge base—the conclusion of the rule must follow regardless of what else is in the knowledge base.

Proof by resolution

We have argued that the inference rules covered so far are sound, but we have not discussed the question of completeness for the inference algorithms that use them. Search algorithms such as iterative deepening search (page 89) are complete in the sense that they will find any reachable goal, but if the available inference rules are inadequate, then the goal is not reachable—no proof exists that uses only B~1,2~ those inference rules. For example, if we removed the biconditional elimination rule, the proof in the preceding section would not go through. The current section introduces a single inference rule, resolution, that yields a complete inference algorithm when coupled with any complete search algorithm.

We begin by using a simple version of the resolution rule in the wumpus world. Let us consider the steps leading up to Figure 7.4(a): the agent returns from [2,1] to [1,1] and then goes to [1,2], where it perceives a stench, but no breeze. We add the following facts to the knowledge base:

R~11~ : ¬B~1,2~ .

R~12~ : B~1,2~ ⇔ (P~1,1~ ∨ P~2,2~ ∨ P~1,3~) .

By the same process that led to R~10~ earlier, we can now derive the absence of pits in [2,2] and [1,3] (remember that [1,1] is already known to be pitless):

R~13~ : ¬P~2,2~ .

R~14~ : ¬P~1,3~ .

We can also apply biconditional elimination to R~3~, followed by Modus Ponens with R~5~, to obtain the fact that there is a pit in [1,1], [2,2], or [3,1]:

R~15~ : P~1,1~ ∨ P~2,2~ ∨ P~3,1~ .

Now comes the first application of the resolution rule: the literal ¬P~2,2~ in R~1~3 resolves with the literal P~2,2~ in R~15~ to give the resolvent

R~16~ : P~1,1~ ∨ P~3,1~ .

In English; if there’s a pit in one of [1,1], [2,2], and [3,1] and it’s not in [2,2], then it’s in [1,1] or [3,1]. Similarly, the literal ¬P~1,1~ in R~1~ resolves with the literal P~1,1~ in R~16~ to give

R~17~ : P~3,1~ .

In English: if there’s a pit in [1,1] or [3,1] and it’s not in [1,1], then it’s in [3,1]. These last two inference steps are examples of the unit resolution inference rule,UNIT RESOLUTION

l~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ l~k~, m

l~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ li−1 ∨ li+1 ∨ · · · ∨ l~k~ ,

where each l is a literal and li and m are complementary literals (i.e., one is the negation of the other). Thus, the unit resolution rule takes a clause—a disjunction of literals—and a literal and produces a new clause. Note that a single literal can be viewed as a disjunction of one literal, also known as a unit clause.

The unit resolution rule can be generalized to the full resolution rule,RESOLUTION

l~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ l~k~, m~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ m~n~ / l~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ l~i−1~ ∨ l~i+1~ ∨ · · · ∨ l~k~ ∨ m~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ m~j−1~ ∨ m~j+1~ ∨ · · · ∨ m~n~,

where li and mj are complementary literals. This says that resolution takes two clauses and produces a new clause containing all the literals of the two original clauses except the two complementary literals. For example, we have

P~1,1~ ∨ P~3,1~, ¬P~1,1~ ∨ ¬P~2,2~ / P~3,1~ ∨ ¬P~2,2~ .

There is one more technical aspect of the resolution rule: the resulting clause should contain only one copy of each literal.9 The removal of multiple copies of literals is called factoring. For example, if we resolve (A ∨B) with (A ∨ ¬B), we obtain (A ∨A), which is reduced to just A.

The soundness of the resolution rule can be seen easily by considering the literal l~i~ that is complementary to literal m~j~ in the other clause. If l~i~ is true, then m~j~ is false, and hence m~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ m~j−1~ ∨ m~j+1~ ∨ · · · ∨ m~n~ must be true, because m~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ m~n~ is given. If l~i~ is false, then l~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ l~i−1~ ∨ l~i+1~ ∨ · · · ∨ l~k~ must be true because l~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ l~k~ is given. Now l~i~ is either true or false, so one or other of these conclusions holds—exactly as the resolution rule states.

What is more surprising about the resolution rule is that it forms the basis for a family of complete inference procedures. A resolution-based theorem prover can, for any sentences α and β in propositional logic, decide whether α |= β_._ The next two subsections explain how resolution accomplishes this.

Conjunctive normal form

The resolution rule applies only to clauses (that is, disjunctions of literals), so it would seem to be relevant only to knowledge bases and queries consisting of clauses. How, then, can it lead to a complete inference procedure for all of propositional logic? The answer is that every sentence of propositional logic is logically equivalent to a conjunction of clauses. A sentence expressed as a conjunction of clauses is said to be in conjunctive normal form or CNF (see Figure 7.14). We now describe a procedure for converting to CNF. We illustrate the procedure by converting the sentence B~1,1~ ⇔ (P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) into CNF. The steps are as follows:

- Eliminate ⇔, replacing α ⇔ β with (α ⇒ β) ∧ (β ⇒ α).

(B~1,1~ ⇒ (P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~)) ∧ ((P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) ⇒ B~1,1~) .

- Eliminate ⇒, replacing α ⇒ β with ¬α ∨ β:

(¬B~1,1~ ∨ P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) ∧ (¬(P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) ∨B~1,1~) .

9 If a clause is viewed as a set of literals, then this restriction is automatically respected. Using set notation for clauses makes the resolution rule much cleaner, at the cost of introducing additional notation.

- CNF requires ¬ to appear only in literals, so we “move ¬ inwards” by repeated application of the following equivalences from Figure 7.11:

¬(¬α) ≡ α (double-negation elimination) ¬(α ∧ β) ≡ (¬α ∨ ¬β) (De Morgan) ¬(α ∨ β) ≡ (¬α ∧ ¬β) (De Morgan)

In the example, we require just one application of the last rule:

(¬B~1,1~ ∨ P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) ∧ ((¬P~1,2~ ∧ ¬P~2,1~) ∨B~1,1~) .

- Now we have a sentence containing nested ∧ and ∨ operators applied to literals. We apply the distributivity law from Figure 7.11, distributing ∨ over ∧ wherever possible.

(¬B~1,1~ ∨ P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) ∧ (¬P~1,2~ ∨B~1,1~) ∧ (¬P~2,1~ ∨B~1,1~) .

The original sentence is now in CNF, as a conjunction of three clauses. It is much harder to read, but it can be used as input to a resolution procedure.

A resolution algorithm

Inference procedures based on resolution work by using the principle of proof by contradiction introduced on page 250. That is, to show that KB |= α, we show that (KB ∧ ¬α) is unsatisfiable. We do this by proving a contradiction.

A resolution algorithm is shown in Figure 7.12. First, (KB ∧ ¬α) is converted into CNF. Then, the resolution rule is applied to the resulting clauses. Each pair that contains complementary literals is resolved to produce a new clause, which is added to the set if it is not already present. The process continues until one of two things happens:

-

there are no new clauses that can be added, in which case KB does not entail α; or,

-

two clauses resolve to yield the empty clause, in which case KB entails α.

The empty clause—a disjunction of no disjuncts—is equivalent to False because a disjunction is true only if at least one of its disjuncts is true. Another way to see that an empty clause represents a contradiction is to observe that it arises only from resolving two complementary unit clauses such as P and ¬P .

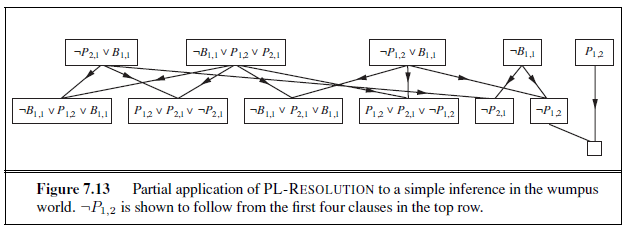

We can apply the resolution procedure to a very simple inference in the wumpus world. When the agent is in [1,1], there is no breeze, so there can be no pits in neighboring squares. The relevant knowledge base is

KB = R~2~ ∧ R~4~ = (B~1,1~ ⇔ (P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~)) ∧ ¬B~1,1~

and we wish to prove α which is, say, ¬P~1,2~. When we convert (KB ∧ ¬α) into CNF, we obtain the clauses shown at the top of Figure 7.13. The second row of the figure shows clauses obtained by resolving pairs in the first row. Then, when P~1,2~ is resolved with ¬P~1,2~, we obtain the empty clause, shown as a small square. Inspection of Figure 7.13 reveals that many resolution steps are pointless. For example, the clause B~1,1~∨¬B~1,1~∨P~1,2~ is equivalent to True ∨ P~1,2~ which is equivalent to True . Deducing that True is true is not very helpful. Therefore, any clause in which two complementary literals appear can be discarded.

function PL-RESOLUTION(KB , α) returns true or false

inputs: KB , the knowledge base, a sentence in propositional logic α, the query, a sentence in propositional logic

clauses← the set of clauses in the CNF representation of KB ∧ ¬α new←{} loop do for each pair of clauses Ci, Cj in clauses do

resolvents← PL-RESOLVE(Ci, Cj ) if resolvents contains the empty clause then return true

new←new ∪ resolvents if new ⊆ clauses then return false clauses← clauses ∪new

Figure 7.12 A simple resolution algorithm for propositional logic. The function PL-RESOLVE returns the set of all possible clauses obtained by resolving its two inputs.

Completeness of resolution

To conclude our discussion of resolution, we now show why PL-RESOLUTION is complete. To do this, we introduce the resolution closure RC (S) of a set of clauses S, which is the set of all clauses derivable by repeated application of the resolution rule to clauses in S or their derivatives. The resolution closure is what PL-RESOLUTION computes as the final value of the variable clauses . It is easy to see that RC (S) must be finite, because there are only finitely many distinct clauses that can be constructed out of the symbols P~1~, . . . , P~k~ that appear in S. (Notice that this would not be true without the factoring step that removes multiple copies of literals.) Hence, PL-RESOLUTION always terminates.

The completeness theorem for resolution in propositional logic is called the ground resolution theorem:

If a set of clauses is unsatisfiable, then the resolution closure of those clauses contains the empty clause.

This theorem is proved by demonstrating its contrapositive: if the closure RC (S) does not contain the empty clause, then S is satisfiable. In fact, we can construct a model for S with suitable truth values for P~1~, . . . , P~k~. The construction procedure is as follows:

For i from 1 to k,

– If a clause in RC (S) contains the literal ¬P~i~ and all its other literals are false under the assignment chosen for P~1~, . . . , P~i−1~, then assign false to P~i~.

– Otherwise, assign true to P~i~.

This assignment to P~1~, . . . , P~k~ is a model of S. To see this, assume the opposite—that, at some stage i in the sequence, assigning symbol P~i~ causes some clause C to become false. For this to happen, it must be the case that all the other literals in C must already have been falsified by assignments to P~1~, . . . , P~i−1~. Thus, C must now look like either (false ∨ false ∨ · · · false ∨ P~i~) or like (false ∨ false ∨ · · · false ∨ ¬P~i~). If just one of these two is in RC(S), then the algorithm will assign the appropriate truth value to P~i to make C true, so C can only be falsified if both of these clauses are in RC(S). Now, since RC(S) is closed under resolution, it will contain the resolvent of these two clauses, and that resolvent will have all of its literals already falsified by the assignments to P~1~, . . . , P~i−1~. This contradicts our assumption that the first falsified clause appears at stage i. Hence, we have proved that the construction never falsifies a clause in RC(S); that is, it produces a model of RC(S) and thus a model of S itself (since S is contained in RC(S)).

Horn clauses and definite clauses

The completeness of resolution makes it a very important inference method. In many practical situations, however, the full power of resolution is not needed. Some real-world knowledge bases satisfy certain restrictions on the form of sentences they contain, which enables them to use a more restricted and efficient inference algorithm.

One such restricted form is the definite clause, which is a disjunction of literals of which exactly one is positive. For example, the clause (¬l~1~,1 ∨ ¬Breeze ∨ B~1,1~) is a definite clause, whereas (¬B~1,1~ ∨ P~1,2~ ∨ P~2,1~) is not.

Slightly more general is the Horn clause, which is a disjunction of literals of which at most one is positive. So all definite clauses are Horn clauses, as are clauses with no positive literals; these are called goal clauses. Horn clauses are closed under resolution: if you resolve two Horn clauses, you get back a Horn clause. Knowledge bases containing only definite clauses are interesting for three reasons:

- Every definite clause can be written as an implication whose premise is a conjunction of positive literals and whose conclusion is a single positive literal. (See Exercise 7.13.) For example, the definite clause (¬l~1,1~ ∨ ¬Breeze ∨ B~1,1~) can be written as the implication (l~1,1~ ∧ Breeze) ⇒ B~1,1~. In the implication form, the sentence is easier to understand: it says that if the agent is in [1,1] and there is a breeze, then [1,1] is breezy. In Horn form, the premise is called the body and the conclusion is called the head. sentence consisting of a single positive literal, such as l~1,1~, is called a fact. It too can FACT be written in implication form as True ⇒ l~1,1~, but it is simpler to write just l~1,1~.

CNFSentence → Clause~1~ ∧ · · · ∧ Clause~n~

Clause → Literal~1~ ∨ · · · ∨ Literal~m~

Literal → Symbol | ¬Symbol

Symbol → P | Q | R | . . .

HornClauseForm → DefiniteClauseForm | GoalClauseForm

DefiniteClauseForm → (Symbol~1~ ∧ · · · ∧ Symbol~l~) ⇒ Symbol

GoalClauseForm → (Symbol~1~ ∧ · · · ∧ Symbol~l~) ⇒ False

Figure 7.14 A grammar for conjunctive normal form, Horn clauses, and definite clauses. A clause such as A ∧ B ⇒ C is still a definite clause when it is written as ¬A ∨ ¬B ∨ C, but only the former is considered the canonical form for definite clauses. One more class is the k-CNF sentence, which is a CNF sentence where each clause has at most k literals.

-

Inference with Horn clauses can be done through the forward-chaining and backwar-chaining algorithms, which we explain next. Both of these algorithms are natural, in that the inference steps are obvious and easy for humans to follow. This type of inference is the basis for logic programming, which is discussed in Chapter 9.

-

Deciding entailment with Horn clauses can be done in time that is linear in the size of the knowledge base—a pleasant surprise.

Forward and backward chaining

The forward-chaining algorithm PL-FC-ENTAILS?(KB , q) determines if a single proposition symbol q—the query—is entailed by a knowledge base of definite clauses. It begins from known facts (positive literals) in the knowledge base. If all the premises of an implication are known, then its conclusion is added to the set of known facts. For example, if L~1,1~ and Breeze are known and (L~1,1~ ∧ Breeze) ⇒ B~1,1~ is in the knowledge base, then B~1,1~ can be added. This process continues until the query q is added or until no further inferences can be made. The detailed algorithm is shown in Figure 7.15; the main point to remember is that it runs in linear time.

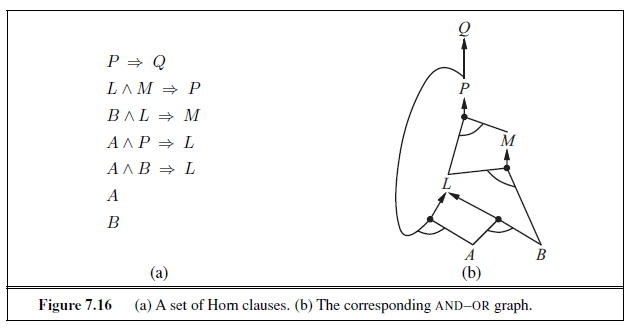

The best way to understand the algorithm is through an example and a P~icture. Figure 7.16(a) shows a simple knowledge base of Horn clauses with A and B as known facts. Figure 7.16(b) shows the same knowledge base drawn as an AND–OR graph (see Chapter 4). In AND–OR graphs, multiple links joined by an arc indicate a conjunction—every link must be proved—while multiple links without an arc indicate a disjunction—any link can be proved. It is easy to see how forward chaining works in the graph. The known leaves (here, A and B) are set, and inference propagates up the graph as far as possible. Wherever a conjunction appears, the propagation waits until all the conjuncts are known before proceeding. The reader is encouraged to work through the example in detail.

function PL-FC-ENTAILS?(KB , q) returns true or false

inputs: KB , the knowledge base, a set of propositional definite clauses q , the query, a proposition symbol

count← a table, where count[c] is the number of symbols in c’s premise inferred← a table, where inferred [s] is initially false for all symbols agenda← a queue of symbols, initially symbols known to be true in KB

while agenda is not empty do p← POP(agenda) if p = q then return true

if inferred [p] = false then inferred [p]← true

for each clause c in KB where p is in c.PREMISE do decrement count[c] if count[c] = 0 then add c.CONCLUSION to agenda

return false

Figure 7.15 The forward-chaining algorithm for propositional logic. The agenda keeps track of symbols known to be true but not yet “processed.” The count table keeps track of how many premises of each implication are as yet unknown. Whenever a new symbol p from the agenda is processed, the count is reduced by one for each implication in whose premise p appears (easily identified in constant time with appropriate indexing.) If a count reaches zero, all the premises of the implication are known, so its conclusion can be added to the agenda. Finally, we need to keep track of which symbols have been processed; a symbol that is already in the set of inferred symbols need not be added to the agenda again. This avoids redundant work and prevents loops caused by implications such as P ⇒ Q and Q⇒ P .

It is easy to see that forward chaining is sound: every inference is essentially an application of Modus Ponens. Forward chaining is also complete: every entailed atomic sentence will be derived. The easiest way to see this is to consider the final state of the inferred table (after the algorithm reaches a fixed point where no new inferences are possible). The table contains true for each symbol inferred during the process, and false for all other symbols. We can view the table as a logical model; moreover, every definite clause in the original KB is true in this model. To see this, assume the opposite, namely that some clause a~1~ ∧. . .∧ a~k~ ⇒ b is false in the model. Then a~1~ ∧ . . . ∧ a~k~ must be true in the model and b must be false in the model. But this contradicts our assumption that the algorithm has reached a fixed point! We can conclude, therefore, that the set of atomic sentences inferred at the fixed point defines a model of the original KB. Furthermore, any atomic sentence q that is entailed by the KB must be true in all its models and in this model in particular. Hence, every entailed atomic sentence q must be inferred by the algorithm.

Forward chaining is an example of the general concept of data-driven reasoning—that is, reasoning in which the focus of attention starts with the known data. It can be used within an agent to derive conclusions from incoming percepts, often without a specific query in mind. For example, the wumpus agent might TELL its percepts to the knowledge base using

an incremental forward-chaining algorithm in which new facts can be added to the agenda to initiate new inferences. In humans, a certain amount of data-driven reasoning occurs as new information arrives. For example, if I am indoors and hear rain starting to fall, it might occur to me that the picnic will be canceled. Yet it will probably not occur to me that the seventeenth petal on the largest rose in my neighbor’s garden will get wet; humans keep forward chaining under careful control, lest they be swamped with irrelevant consequences.

The backward-chaining algorithm, as its name suggests, works backward from the query. If the query q is known to be true, then no work is needed. Otherwise, the algorithm finds those implications in the knowledge base whose conclusion is q . If all the premises of one of those implications can be proved true (by backward chaining), then q is true. When applied to the query Q in Figure 7.16, it works back down the graph until it reaches a set of known facts, A and B, that forms the basis for a proof. The algorithm is essentially identical to the AND-OR-GRAPH-SEARCH algorithm in Figure 4.11. As with forward chaining, an efficient implementation runs in linear time.

Backward chaining is a form of goal-directed reasoning. It is useful for answering specific questions such as “What shall I do now?” and “Where are my keys?” Often, the cost of backward chaining is much less than linear in the size of the knowledge base, because the process touches only relevant facts.

EFFECTIVE PROPOSITIONAL MODEL CHECKING

In this section, we describe two families of efficient algorithms for general propositional inference based on model checking: One approach based on backtracking search, and one on local hill-climbing search. These algorithms are part of the “technology” of propositional logic. This section can be skimmed on a first reading of the chapter.

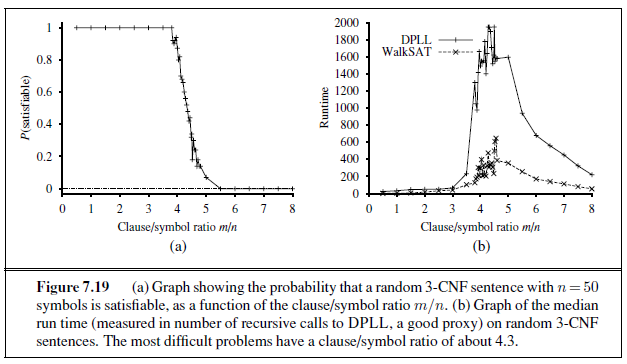

The algorithms we describe are for checking satisfiability: the SAT problem. (As noted earlier, testing entailment, α |= β, can be done by testing unsatisfiability of α ∧ ¬β.) We have already noted the connection between finding a satisfying model for a logical sentence and finding a solution for a constraint satisfaction problem, so it is perhaps not surprising that the two families of algorithms closely resemble the backtracking algorithms of Section 6.3 and the local search algorithms of Section 6.4. They are, however, extremely important in their own right because so many combinatorial problems in computer science can be reduced to checking the satisfiability of a propositional sentence. Any improvement in satisfiability algorithms has huge consequences for our ability to handle complexity in general.

A complete backtracking algorithm

The first algorithm we consider is often called the Davis–Putnam algorithm, after the seminal paper by Martin Davis and Hilary Putnam (1960). The algorithm is in fact the version described by Davis, Logemann, and Loveland (1962), so we will call it DPLL after the initials of all four authors. DPLL takes as input a sentence in conjunctive normal form—a set of clauses. Like BACKTRACKING-SEARCH and TT-ENTAILS?, it is essentially a recursive, depth-first enumeration of possible models. It embodies three improvements over the simple scheme of TT-ENTAILS?:

-

Early termination: The algorithm detects whether the sentence must be true or false, even with a partially completed model. A clause is true if any literal is true, even if the other literals do not yet have truth values; hence, the sentence as a whole could be judged true even before the model is complete. For example, the sentence (A ∨ B) ∧ (A ∨ C) is true if A is true, regardless of the values of B and C . Similarly, a sentence is false if any clause is false, which occurs when each of its literals is false. Again, this can occur long before the model is complete. Early termination avoids examination of entire subtrees in the search space.

-

Pure symbol heuristic: A pure symbol is a symbol that always appears with the same “sign” in all clauses. For example, in the three clauses (A ∨ ¬B), (¬B ∨ ¬C), and (C ∨ A), the symbol A is pure because only the positive literal appears, B is pure because only the negative literal appears, and C is impure. It is easy to see that if a sentence has a model, then it has a model with the pure symbols assigned so as to make their literals true , because doing so can never make a clause false. Note that, in determining the purity of a symbol, the algorithm can ignore clauses that are already known to be true in the model constructed so far. For example, if the model contains B = false , then the clause (¬B ∨ ¬C) is already true, and in the remaining clauses C appears only as a positive literal; therefore C becomes pure.

-

Unit clause heuristic: A unit clause was defined earlier as a clause with just one literal. In the context of DPLL, it also means clauses in which all literals but one are already assigned false by the model. For example, if the model contains B = true , then (¬B ∨ ¬C) simplifies to ¬C , which is a unit clause. Obviously, for this clause to be true, C must be set to false . The unit clause heuristic assigns all such symbols before branching on the remainder. One important consequence of the heuristic is that

function DPLL-SATISFIABLE?(s) returns true or false inputs: s , a sentence in propositional logic

clauses← the set of clauses in the CNF representation of s symbols← a list of the proposition symbols in s return DPLL(clauses , symbols ,{ })

function DPLL(clauses , symbols ,model ) returns true or false

if every clause in clauses is true in model then return true if some clause in clauses is false in model then return false P , value← FIND-PURE-SYMBOL(symbols , clauses ,model ) if P is non-null then return DPLL(clauses , symbols – P ,model ∪ {P=value}) P , value← FIND-UNIT-CLAUSE(clauses ,model ) if P is non-null then return DPLL(clauses , symbols – P ,model ∪ {P=value}) P← FIRST(symbols); rest←REST(symbols) return DPLL(clauses , rest ,model ∪ {P=true}) or DPLL(clauses , rest ,model ∪ {P=false})

Figure 7.17 The DPLL algorithm for checking satisfiability of a sentence in propositional logic. The ideas behind FIND-PURE-SYMBOL and FIND-UNIT-CLAUSE are described in the text; each returns a symbol (or null) and the truth value to assign to that symbol. Like TT-ENTAILS?, DPLL operates over partial models.

any attempt to prove (by refutation) a literal that is already in the knowledge base will succeed immediately (Exercise 7.23). Notice also that assigning one unit clause can create another unit clause—for example, when C is set to false , (C ∨ A) becomes a unit clause, causing true to be assigned to A. This “cascade” of forced assignments is called unit propagation. It resembles the process of forward chaining with definite clauses, and indeed, if the CNF expression contains only definite clauses then DPLL essentially replicates forward chaining. (See Exercise 7.24.)

The DPLL algorithm is shown in Figure 7.17, which gives the the essential skeleton of the search process.

What Figure 7.17 does not show are the tricks that enable SAT solvers to scale up to large problems. It is interesting that most of these tricks are in fact rather general, and we have seen them before in other guises:

-

Component analysis (as seen with Tasmania in CSPs): As DPLL assigns truth values to variables, the set of clauses may become separated into disjoint subsets, called components, that share no unassigned variables. Given an efficient way to detect when this occurs, a solver can gain considerable speed by working on each component separately.

-

Variable and value ordering (as seen in Section 6.3.1 for CSPs): Our simple implementation of DPLL uses an arbitrary variable ordering and always tries the value true before false. The degree heuristic (see page 216) suggests choosing the variable that appears most frequently over all remaining clauses.

-

Intelligent backtracking (as seen in Section 6.3 for CSPs): Many problems that cannot be solved in hours of run time with chronological backtracking can be solved in seconds with intelligent backtracking that backs up all the way to the relevant point of conflict. All SAT solvers that do intelligent backtracking use some form of conflict clause learning to record conflicts so that they won’t be repeated later in the search. Usually a limited-size set of conflicts is kept, and rarely used ones are dropped.

-

Random restarts (as seen on page 124 for hill-climbing): Sometimes a run appears not to be making progress. In this case, we can start over from the top of the search tree, rather than trying to continue. After restarting, different random choices (in variable and value selection) are made. Clauses that are learned in the first run are retained after the restart and can help prune the search space. Restarting does not guarantee that a solution will be found faster, but it does reduce the variance on the time to solution.

-

Clever indexing (as seen in many algorithms): The speedup methods used in DPLL itself, as well as the tricks used in modern solvers, require fast indexing of such things as “the set of clauses in which variable Xi appears as a positive literal.” This task is complicated by the fact that the algorithms are interested only in the clauses that have not yet been satisfied by previous assignments to variables, so the indexing structures must be updated dynamically as the computation proceeds.

With these enhancements, modern solvers can handle problems with tens of millions of variables. They have revolutionized areas such as hardware verification and security protocol verification, which previously required laborious, hand-guided proofs.

Local search algorithms

We have seen several local search algorithms so far in this book, including (page 122) and SIMULATED-ANNEALING (page 126). These algorithms can be applied directly to satisfiability problems, provided that we choose the right evaluation function. Because the goal is to find an assignment that satisfies every clause, an evaluation function that counts the number of unsatisfied clauses will do the job. In fact, this is exactly the measure used by the MIN-CONFLICTS algorithm for CSPs (page 221). All these algorithms take steps in the space of complete assignments, flipping the truth value of one symbol at a time. The space usually contains many local minima, to escape from which various forms of randomness are required. In recent years, there has been a great deal of experimentation to find a good balance between greediness and randomness.

One of the simplest and most effective algorithms to emerge from all this work is called WAlkSAT (Figure 7.18). On every iteration, the algorithm picks an unsatisfied clause and picks a symbol in the clause to flip. It chooses randomly between two ways to pick which symbol to flip: (1) a “min-conflicts” step that minimizes the number of unsatisfied clauses in the new state and (2) a “random walk” step that picks the symbol randomly.

When WALKSAT returns a model, the input sentence is indeed satisfiable, but when it returns failure , there are two possible causes: either the sentence is unsatisfiable or we need to give the algorithm more time. If we set max flips = ∞ and p > 0, WALKSAT will eventually return a model (if one exists), because the random-walk steps will eventually hit

function WALKSAT(clauses ,p,max flips) returns a satisfying model or failure inputs: clauses , a set of clauses in propositional logic p, the probability of choosing to do a “random walk” move, typically around 0.5 max flips , number of flips allowed before giving up

model← a random assignment of true/false to the symbols in clauses for i = 1 to max flips do if model satisfies clauses then return model

clause← a randomly selected clause from clauses that is false in model

with probability p flip the value in model of a randomly selected symbol from clause

else flip whichever symbol in clause maximizes the number of satisfied clauses return failure

Figure 7.18 The WALKSAT algorithm for checking satisfiability by randomly flipping the values of variables. Many versions of the algorithm exist.

upon the solution. Alas, if max flips is infinity and the sentence is unsatisfiable, then the algorithm never terminates!