NATURAL LANGUAGE PROCESSING

In which we see how to make use of the copious knowledge that is expressed in natural language.

Homo sapiens is set apart from other species by the capacity for language. Somewhere around 100,000 years ago, humans learned how to speak, and about 7,000 years ago learned to write. Although chimpanzees, dolphins, and other animals have shown vocabularies of hundreds of signs, only humans can reliably communicate an unbounded number of qualitatively different messages on any topic using discrete signs.

Of course, there are other attributes that are uniquely human: no other species wears clothes, creates representational art, or watches three hours of television a day. But when Alan Turing proposed his Test (see Section 1.1.1), he based it on language, not art or TV. There are two main reasons why we want our computer agents to be able to process natural languages: first, to communicate with humans, a topic we take up in Chapter 23, and second, to acquire information from written language, the focus of this chapter.

There are over a trillion pages of information on the Web, almost all of it in natural language. An agent that wants to do knowledge acquisition needs to understand (at leastKNOWLEDGE ACQUISITION partially) the ambiguous, messy languages that humans use. We examine the problem from the point of view of specific information-seeking tasks: text classification, information retrieval, and information extraction. One common factor in addressing these tasks is the use of language models: models that predict the probability distribution of language expressions.

LANGUAGE MODELS

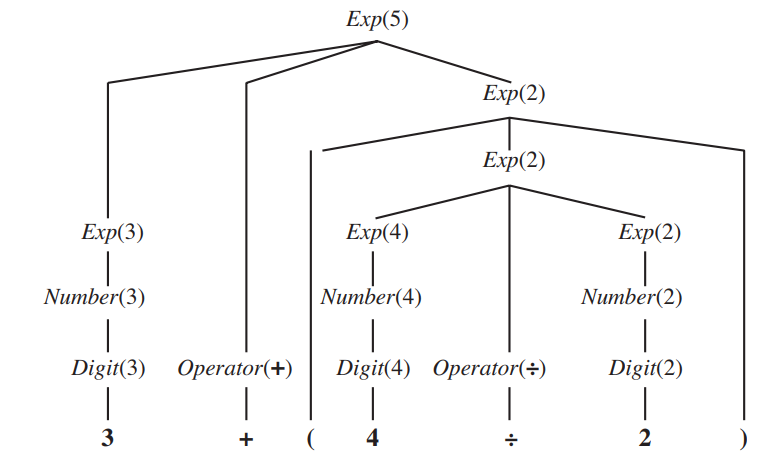

Formal languages, such as the programming languages Java or Python, have precisely defined language models. A language can be defined as a set of strings; “print(2 + 2)” is a legal program in the language Python, whereas “(2+2) print” is not. Since there are an infinite number of legal programs, they cannot be enumerated; instead they are specified by a set of rules called a grammar*. Formal languages also have rules that define the meaning or semantics of a program; for example, the rules say that the “meaning” of “2 + 2” is 4, and the meaning of “1/0” is that an error is signaled.

Natural languages, such as English or Spanish, cannot be characterized as a definitive set of sentences. Everyone agrees that “Not to be invited is sad” is a sentence of English, but people disagree on the grammaticality of “To be not invited is sad.” Therefore, it is more fruitful to define a natural language model as a probability distribution over sentences rather than a definitive set. That is, rather than asking if a string of words is or is not a member of the set defining the language, we instead ask for P (S =words)—what is the probability that a random sentence would be words.

Natural languages are also ambiguous. “He saw her duck” can mean either that he saw a waterfowl belonging to her, or that he saw her move to evade something. Thus, again, we cannot speak of a single meaning for a sentence, but rather of a probability distribution over possible meanings.

Finally, natural languages are difficult to deal with because they are very large, and constantly changing. Thus, our language models are, at best, an approximation. We start with the simplest possible approximations and move up from there.

N-gram character models

Ultimately, a written text is composed of letters, digits, punctuation, and spaces in English (and more exotic characters in some other languages). Thus, one of the simplest language models is a probability distribution over sequences of characters. As in Chapter 15, we write P (c~1:N~ ) for the probability of a sequence of N characters, C~1~ through c~N~ . In one Web collection, P (“the”)= 0.027 and P (“zgq”)= 0.000000002. A sequence of written symbols of length n is called an n-gram (from the Greek root for writing or letters), with special case “unigram” for 1-gram, “bigram” for 2-gram, and “trigram” for 3-gram. A model of the probability distribution of n-letter sequences is thus called an n-gram model. (But be care-N ful: we can have n-gram models over sequences of words, syllables, or other units; not just over characters.)

An n-gram model is defined as a Markov chain of order n − 1. Recall from page 568 that in a Markov chain the probability of character c~i~ depends only on the immediately preceding characters, not on any other characters. So in a trigram model (Markov chain of order 2) we have

P (c~i~ | C~1:i−1~) = P (c~i~ | c~i−2:i−1~) .

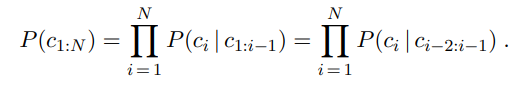

We can define the probability of a sequence of characters P (C~1~:N ) under the trigram model by first factoring with the chain rule and then using the Markov assumption:

For a trigram character model in a language with 100 characters, P(C~i~|C~i−2:i−1~) has a million entries, and can be accurately estimated by counting character sequences in a body of text of 10 million characters or more. We call a body of text a corpus (plural corpora), from the Latin word for body.

What can we do with n-gram character models? One task for which they are well suited is language identification: given a text, determine what natural language it is written in. This is a relatively easy task; even with short texts such as “Hello, world” or “Wie geht es dir,” it is easy to identify the first as English and the second as German. Computer systems identify languages with greater than 99% accuracy; occasionally, closely related languages, such as Swedish and Norwegian, are confused.

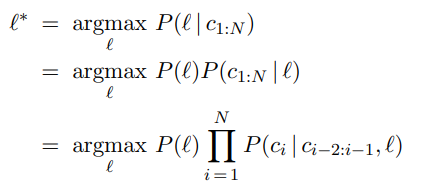

One approach to language identification is to first build a trigram character model of each candidate language, P (c~i~ | c~i−2:i−1~, ), where the variable ranges over languages. For each the model is built by counting trigrams in a corpus of that language. (About 100,000 characters of each language are needed.) That gives us a model of P(Text |Language), but we want to select the most probable language given the text, so we apply Bayes’ rule followed by the Markov assumption to get the most probable language:

The trigram model can be learned from a corpus, but what about the prior probability P ()? We may have some estimate of these values; for example, if we are selecting a random Web page we know that English is the most likely language and that the probability of Macedonian will be less than 1%. The exact number we select for these priors is not critical because the trigram model usually selects one language that is several orders of magnitude more probable than any other.

Other tasks for character models include spelling correction, genre classification, and named-entity recognition. Genre classification means deciding if a text is a news story, a legal document, a scientific article, etc. While many features help make this classification, counts of punctuation and other character n-gram features go a long way (Kessler et al., 1997). Named-entity recognition is the task of finding names of things in a document and deciding what class they belong to. For example, in the text “Mr. Sopersteen was prescribed aciphex,” we should recognize that “Mr. Sopersteen” is the name of a person and “aciphex” is the name of a drug. Character-level models are good for this task because they can associate the character sequence “ex ” (“ex” followed by a space) with a drug name and “steen ” with a person name, and thereby identify words that they have never seen before.

Smoothing n-gram models

The major complication of n-gram models is that the training corpus provides only an estimate of the true probability distribution. For common character sequences such as “ th” any English corpus will give a good estimate: about 1.5% of all trigrams. On the other hand, “ ht” is very uncommon—no dictionary words start with ht. It is likely that the sequence would have a count of zero in a training corpus of standard English. Does that mean we should assign P (“ th”)= 0? If we did, then the text “The program issues an http request” would have an English probability of zero, which seems wrong. We have a problem in generalization: we want our language models to generalize well to texts they haven’t seen yet. Just because we have never seen “ http” before does not mean that our model should claim that it is impossible. Thus, we will adjust our language model so that sequences that have a count of zero in the training corpus will be assigned a small nonzero probability (and the other counts will be adjusted downward slightly so that the probability still sums to 1). The process od adjusting the probability of low-frequency counts is called smoothing.

The simplest type of smoothing was suggested by Pierre-Simon Laplace in the 18th century: he said that, in the lack of further information, if a random Boolean variable X has been false in all n observations so far then the estimate for P (X = true) should be 1/(n+2). That is, he assumes that with two more trials, one might be true and one false. Laplace smoothing (also called add-one smoothing) is a step in the right direction, but performs relatively poorly. A better approach is a backoff model, in which we start by estimating n-gram counts, but for any particular sequence that has a low (or zero) count, we back off to (n− 1)-grams. Linear interpolation smoothing is a backoff model that combines trigram, bigram, and unigram models by linear interpolation. It defines the probability estimate as

P̂ (c~i~|c~i−2:i−1~) = λ3P (c~i~|c~i−2:i−1~) + λ2P (c~i|ci−1~) + λ1P (c~i~) ,

where λ~3~ + λ~2~ + λ~1~ =1. The parameter values λi can be fixed, or they can be trained with an expectation–maximization algorithm. It is also possible to have the values of λi depend on the counts: if we have a high count of trigrams, then we weigh them relatively more; if only a low count, then we put more weight on the bigram and unigram models. One camp of researchers has developed ever more sophisticated smoothing models, while the other camp suggests gathering a larger corpus so that even simple smoothing models work well. Both are getting at the same goal: reducing the variance in the language model.

One complication: note that the expression P (c~i~ | c~i−2:i−1~) asks for P (C~1~ | c~-1:0~) when i = 1, but there are no characters before C~1~. We can introduce artificial characters, for example, defining c~0~ to be a space character or a special “begin text” character. Or we can fall back on lower-order Markov models, in effect defining c-1:0 to be the empty sequence and thus P (C~1~ | c~-1:0~)= P (C~1~).

Model evaluation

With so many possible n-gram models—unigram, bigram, trigram, interpolated smoothing with different values of λ, etc.—how do we know what model to choose? We can evaluate a model with cross-validation. Split the corpus into a training corpus and a validation corpus. Determine the parameters of the model from the training data. Then evaluate the model on the validation corpus.

The evaluation can be a task-specific metric, such as measuring accuracy on language identification. Alternatively we can have a task-independent model of language quality: calculate the probability assigned to the validation corpus by the model; the higher the probability the better. This metric is inconvenient because the probability of a large corpus will be a very small number, and floating-point underflow becomes an issue. A different way of describing the probability of a sequence is with a measure called perplexity, defined as

Perplexity(C~1~:N ) = P (C~1~:N )^1/N^

Perplexity can be thought of as the reciprocal of probability, normalized by sequence length. It can also be thought of as the weighted average branching factor of a model. Suppose there are 100 characters in our language, and our model says they are all equally likely. Then for a sequence of any length, the perplexity will be 100. If some characters are more likely than others, and the model reflects that, then the model will have a perplexity less than 100.

N-gram word models

Now we turn to n-gram models over words rather than characters. All the same mechanism applies equally to word and character models. The main difference is that the vocabulary the set of symbols that make up the corpus and the model—is larger. There are only about 100 characters in most languages, and sometimes we build character models that are even more restrictive, for example by treating “A” and “a” as the same symbol or by treating all punctuation as the same symbol. But with word models we have at least tens of thousands of symbols, and sometimes millions. The wide range is because it is not clear what constitutes a word. In English a sequence of letters surrounded by spaces is a word, but in some languages, like Chinese, words are not separated by spaces, and even in English many decisions must be made to have a clear policy on word boundaries: how many words are in “ne’er-do-well”? Or in “(Tel:1-800-960-5660x123)”?

Word n-gram models need to deal with out of vocabulary words. With character models, we didn’t have to worry about someone inventing a new letter of the alphabet.1 But with word models there is always the chance of a new word that was not seen in the training corpus, so we need to model that explicitly in our language model. This can be done by adding just one new word to the vocabulary:

To get a feeling for what word models can do, we built unigram, bigram, and trigram models over the words in this book and then randomly sampled sequences of words from the models. The results are

Unigram: logical are as are confusion a may right tries agent goal the was . . .

Bigram: systems are very similar computational approach would be represented . . .

Trigram: planning and scheduling are integrated the success of naive bayes model is . . .

Even with this small sample, it should be clear that the unigram model is a poor approximation of either English or the content of an AI textbook, and that the bigram and trigram models are much better. The models agree with this assessment: the perplexity was 891 for the unigram model, 142 for the bigram model and 91 for the trigram model.

With the basics of n-gram models—both characterand word-based—established, we can turn now to some language tasks.

TEXT CLASSIFICATION

We now consider in depth the task of text classification, also known as categorization: given a text of some kind, decide which of a predefined set of classes it belongs to. Language identification and genre classification are examples of text classification, as is sentiment analysis (classifying a movie or product review as positive or negative) and spam detection (classifying an email message as spam or not-spam). Since “not-spam” is awkward, researchers have coined the term ham for not-spam. We can treat spam detection as a problem in supervised learning. A training set is readily available: the positive (spam) examples are in my spam folder, the negative (ham) examples are in my inbox. Here is an excerpt:

Spam: Wholesale Fashion Watches -57% today. Designer watches for cheap … Spam: You can buy ViagraFr$1.85 All Medications at unbeatable prices! … Spam: WE CAN TREAT ANYTHING YOU SUFFER FROM JUST TRUST US… Spam: Sta.rt earn*ing the salary yo,u d-eserve by o’btaining the prope,r crede’ntials!

Ham: The practical significance of hypertree width in identifying more … Ham: Abstract: We will motivate the problem of social identity clustering: … Ham: Good to see you my friend. Hey Peter, It was good to hear from you. … Ham: PDS implies convexity of the resulting optimization problem Kernel Ridge …

From this excerpt we can start to get an idea of what might be good features to include in the supervised learning model. Word n-grams such as “for cheap” and “You can buy” seem to be indicators of spam (although they would have a nonzero probability in ham as well). Character-level features also seem important: spam is more likely to be all uppercase and to have punctuation embedded in words. Apparently the spammers thought that the word bigram “you deserve” would be too indicative of spam, and thus wrote “yo,u d-eserve” instead. A character model should detect this. We could either create a full character n-gram model of spam and ham, or we could handcraft features such as “number of punctuation marks embedded in words.”

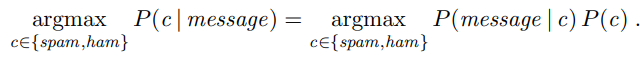

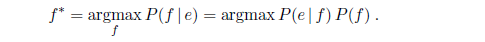

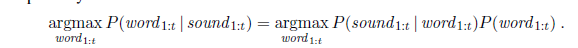

Note that we have two complementary ways of talking about classification. In the language-modeling approach, we define one n-gram language model for P(Message | spam) by training on the spam folder, and one model for P(Message | ham) by training on the inbox. Then we can classify a new message with an application of Bayes’ rule:

where P (c) is estimated just by counting the total number of spam and ham messages. This approach works well for spam detection, just as it did for language identification.

In the machine-learning approach we represent the message as a set of feature/value pairs and apply a classification algorithm h to the feature vector X. We can make the language-modeling and machine-learning approaches compatible by thinking of the n-grams as features. This is easiest to see with a unigram model. The features are the words in the vocabulary: “a,” “aardvark,” and the values are the number of times each word appears in the message. That makes the feature vector large and sparse. If there are 100,000 words in the language model, then the feature vector has length 100,000, but for a short email message almost all the features will have count zero. This unigram representation has been called the bag of words model. You can think of the model as putting the words of the training corpusin a bag and then selecting words one at a time. The notion of order of the words is lost; a unigram model gives the same probability to any permutation of a text. Higher-order n-gram models maintain some local notion of word order.

With bigrams and trigrams the number of features is squared or cubed, and we can add in other, non-n-gram features: the time the message was sent, whether a URL or an image is part of the message, an ID number for the sender of the message, the sender’s number of previous spam and ham messages, and so on. The choice of features is the most important part of creating a good spam detector—more important than the choice of algorithm for processing the features. In part this is because there is a lot of training data, so if we can propose a feature, the data can accurately determine if it is good or not. It is necessary to constantly update features, because spam detection is an adversarial task; the spammers modify their spam in response to the spam detector’s changes.

It can be expensive to run algorithms on a very large feature vector, so often a process of feature selection is used to keep only the features that best discriminate between spam and ham. For example, the bigram “of the” is frequent in English, and may be equally frequent in spam and ham, so there is no sense in counting it. Often the top hundred or so features do a good job of discriminating between classes.

Once we have chosen a set of features, we can apply any of the supervised learning techniques we have seen; popular ones for text categorization include k-nearest-neighbors, support vector machines, decision trees, naive Bayes, and logistic regression. All of these have been applied to spam detection, usually with accuracy in the 98%–99% range. With a carefully designed feature set, accuracy can exceed 99.9%.

Classification by data compression

Another way to think about classification is as a problem in data compression. A lossless compression algorithm takes a sequence of symbols, detects repeated patterns in it, and writes a description of the sequence that is more compact than the original. For example, the text “0.142857142857142857” might be compressed to “0.[142857]*3.” Compression algorithms work by building dictionaries of subsequences of the text, and then referring to entries in the dictionary. The example here had only one dictionary entry, “142857.”

In effect, compression algorithms are creating a language model. The LZW algorithm in particular directly models a maximum-entropy probability distribution. To do classification by compression, we first lump together all the spam training messages and compress them as a unit. We do the same for the ham. Then when given a new message to classify, we append it to the spam messages and compress the result. We also append it to the ham and compress that. Whichever class compresses better—adds the fewer number of additional bytes for the new message—is the predicted class. The idea is that a spam message will tend to share dictionary entries with other spam messages and thus will compress better when appended to a collection that already contains the spam dictionary.

Experiments with compression-based classification on some of the standard corpora for text classification—the 20-Newsgroups data set, the Reuters-10 Corpora, the Industry Sector corpora—indicate that whereas running off-the-shelf compression algorithms like gzip, RAR, and LZW can be quite slow, their accuracy is comparable to traditional classification algorithms. This is interesting in its own right, and also serves to point out that there is promise for algorithms that use character n-grams directly with no preprocessing of the text or feature selection: they seem to be captiring some real patterns.

INFORMATION RETRIEVAL

Information retrieval is the task of finding documents that are relevant to a user’s need for information. The best-known examples of information retrieval systems are search engines on the World Wide Web. A Web user can type a query such as [AI book] into a search engine and see a list of relevant pages. In this section, we will see how such systems are built. An information retrieval (henceforth IR) system can be characterized by

-

A corpus of documents. Each system must decide what it wants to treat as a document: a paragraph, a page, or a multipage text.

-

Queries posed in a query language. A query specifies what the user wants to know.The query language can be just a list of words, such as YHN8[AI bookYHN8]; or it can specify a phrase of words that must be adjacent, as in [“AI book”]; it can contain Boolean operators as in [AI AND book]; it can include non-Boolean operators such as [AI NEAR book] or [AI book site:www.aaai.org].

-

A result set. This is the subset of documents that the IR system judges to be relevant to the query. By relevant, we mean likely to be of use to the person who posed the query, for the particular information need expressed in the query.

-

A presentation of the result set. This can be as simple as a ranked list of document titles or as complex as a rotating color map of the result set projected onto a threedimensional space, rendered as a two-dimensional display.

The earliest IR systems worked on a Boolean keyword model. Each word in the document collection is treated as a Boolean feature that is true of a document if the word occurs in the document and false if it does not. So the feature “retrieval” is true for the current chapter but false for Chapter 15. The query language is the language of Boolean expressions over features. A document is relevant only if the expression evaluates to true. For example, the query [information AND retrieval] is true for the current chapter and false for Chapter 15.

This model has the advantage of being simple to explain and implement. However, it has some disadvantages. First, the degree of relevance of a document is a single bit, so there is no guidance as to how to order the relevant documents for presentation. Second, Boolean expressions are unfamiliar to users who are not programmers or logicians. Users find it unintuitive that when they want to know about farming in the states of Kansas and Nebraska they need to issue the query [farming (Kansas OR Nebraska)]. Third, it can be hard to formulate an appropriate query, even for a skilled user. Suppose we try [information AND retrieval AND models AND optimization] and get an empty result set. We could try [information OR retrieval OR models OR optimization], but if that returns too many results, it is difficult to know what to try next.

IR scoring functions

Most IR systems have abandoned the Boolean model and use models based on the statistics of word counts. We describe the BM25 scoring function, which comes from the Okapi project of Stephen Robertson and Karen Sparck Jones at London’s City College, and has been used in search engines such as the open-source Lucene project.

A scoring function takes a document and a query and returns a numeric score; the most relevant documents have the highest scores. In the BM25 function, the score is a linear weighted combination of scores for each of the words that make up the query. Three factors affect the weight of a query term: First, the frequency with which a query term appears in a document (also known as TF for term frequency). For the query [farming in Kansas], documents that mention “farming” frequently will have higher scores. Second, the inverse document frequency of the term, or IDF . The word “in” appears in almost every document, so it has a high document frequency, and thus a low inverse document frequency, and thus it is not as important to the query as “farming” or “Kansas.” Third, the length of the document. A million-word document will probably mention all the query words, but may not actually be about the query. A short document that mentions all the words is a much better candidate.

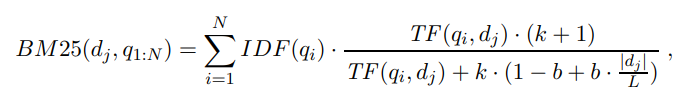

The BM25 function takes all three of these into account. We assume we have created an index of the N documents in the corpus so that we can look up TF (qi, dj), the count of the number of times word qi appears in document dj . We also assume a table of document frequency counts, DF (qi), that gives the number of documents that contain the word qi. Then, given a document dj and a query consisting of the words q1:N , we have

where |dj | is the length of document dj in words, and L is the average document length in the corpus: L = ∑ i |d~i~|/N . We have two parameters, k and b, that can be tuned by cross-validation; typical values are k = 2.0 and b = 0.75. IDF (qi) is the inverse document frequency of word qi, given by

Of course, it would be impractical to apply the BM25 scoring function to every document in the corpus. Instead, systems create an index ahead of time that lists, for each vocabulary word, the documents that contain the word. This is called the hit list for the word. Then when given a query, we intersect the hit lists of the query words and only score the documents in the intersection.

IR system evaluation

How do we know whether an IR system is performing well? We undertake an experiment in which the system is given a set of queries and the result sets are scored with respect to human relevance judgments. Traditionally, there have been two measures used in the scoring: recall and precision. We explain them with the help of an example. Imagine that an IR system has returned a result set for a single query, for which we know which documents are and are not relevant, out of a corpus of 100 documents. The document counts in each category are given in the following table:

| In result set | Not in result set | |

|---|---|---|

| Relevant | 30 | 20 |

| Not relevant | 10 | 40 |

Precision measures the proportion of documents in the result set that are actually relevant. In our example, the precision is 30/(30 + 10)= .75. The false positive rate is 1− .75 = .25. Recall measures the proportion of all the relevant documents in the collection that are in the result set. In our example, recall is 30/(30 + 20)= .60. The false negative rate is 1 −.60 = .40. In a very large document collection, such as the World Wide Web, recall is difficult to compute, because there is no easy way to examine every page on the Web for relevance. All we can do is either estimate recall by sampling or ignore recall completely and just judge precision. In the case of a Web search engine, there may be thousands of documents in the result set, so it makes more sense to measure precision for several different sizes, such as “P@10” (precision in the top 10 results) or “P@50,” rather than to estimate precision in the entire result set.

It is possible to trade off precision against recall by varying the size of the result set returned. In the extreme, a system that returns every document in the document collection is guaranteed a recall of 100%, but will have low precision. Alternately, a system could return a single document and have low recall, but a decent chance at 100% precision. A summary of both measures is the f~1~ score, a single number that is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, 2PR/(P + R).

IR refinements

There are many possible refinements to the system described here, and indeed Web search engines are continually updating their algorithms as they discover new approaches and as the Web grows and changes.

One common refinement is a better model of the effect of document length on relevance. Singhal et al. (1996) observed that simple document length normalization schemes tend to favor short documents too much and long documents not enough. They propose a pivoted document length normalization scheme; the idea is that the pivot is the document length at which the old-style normalization is correct; documents shorter than that get a boost and longer ones get a penalty.

The BM25 scoring function uses a word model that treats all words as completely independent, but we know that some words are correlated: “couch” is closely related to both “couches” and “sofa.” Many IR systems attempt to account for these correlations.

For example, if the query is [couch], it would be a shame to exclude from the result set those documents that mention “COUCH” or “couches” but not “couch.” Most IR systems do case folding of “COUCH” to “couch,” and some use a stemming algorithm to reduce “couches” to the stem form “couch,” both in the query and the documents. This typically yields a small increase in recall (on the order of 2% for English). However, it can harm precision. For example, stemming “stocking” to “stock” will tend to decrease precision for queries about either foot coverings or financial instruments, although it could improve recall for queries about warehousing. Stemming algorithms based on rules (e.g., remove “-ing”) cannot avoid this problem, but algorithms based on dictionaries (don’t remove “-ing” if the word is already listed in the dictionary) can. While stemming has a small effect in English, it is more important in other languages. In German, for example, it is not uncommon to see words like “Lebensversicherungsgesellschaftsangestellter” (life insurance company employee). Languages such as Finnish, Turkish, Inuit, and Yupik have recursive morphological rules that in principle generate words of unbounded length.

The next step is to recognize synonyms, such as “sofa” for “couch.” As with stemming,this has the potential for small gains in recall, but can hurt precision. A user who gives the query [Tim Couch] wants to see results about the football player, not sofas. The problem is that “languages abhor absolute synonyms just as nature abhors a vacuum” (Cruse, 1986). That is, anytime there are two words that mean the same thing, speakers of the language conspire to evolve the meanings to remove the confusion. Related words that are not synonyms also play an important role in ranking—terms like “leather”, “wooden,” or “modern” can serve to confirm that the document really is about “couch.” Synonyms and related words can be found in dictionaries or by looking for correlations in documents or in queries—if we find that many users who ask the query [new sofa] follow it up with the query [new couch], we can in the future alter [new sofa] to be [new sofa OR new couch].

As a final refinement, IR can be improved by considering metadata—data outside of the text of the document. Examples include human-supplied keywords and publication data. On the Web, hypertext links between documents are a crucial source of information.

The PageRank algorithm

PageRank^3^ was one of the two original ideas that set Google’s search apart from other Web search engines when it was introduced in 1997. (The other innovation was the use of anchor

text—the underlined text in a hyperlink—to index a page, even though the anchor text was on a different page than the one being indexed.) PageRank was invented to solve the problem of the tyranny of TF scores: if the query is [IBM], how do we make sure that IBM’s home page, ibm.com, is the first result, even if another page mentions the term “IBM” more frequently? The idea is that ibm.com has many in-links (links to the page), so it should be ranked higher: each in-link is a vote for the quality of the linked-to page. But if we only counted in-links, then it would be possible for a Web spammer to create a network of pages and have them all point to a page of his choosing, increasing the score of that page. Therefore, the PageRank algorithm is designed to weight links from high-quality sites more heavily. What is a highquality site? One that is linked to by other high-quality sites. The definition is recursive, but we will see that the recursion bottoms out properly. The PageRank for a page p is defined as:

where PR(p) is the PageRank of page p, N is the total number of pages in the corpus, in~i~ are the pages that link in to p, and C(ini) is the count of the total number of out-links on page ini. The constant d is a damping factor. It can be understood through the random surfer model: imagine a Web surfer who starts at some random page and begins exploring. With probability d (we’ll assume d= 0.85) the surfer clicks on one of the links on the page (choosing uniformly among them), and with probability 1 − d she gets bored with the page and restarts on a random page anywhere on the Web. The PageRank of page p is then the probability that the random surfer will be at page p at any point in time. PageRank can be computed by an iterative procedure: start with all pages having PR(p)= 1, and iterate the algorithm, updating ranks until they converge.

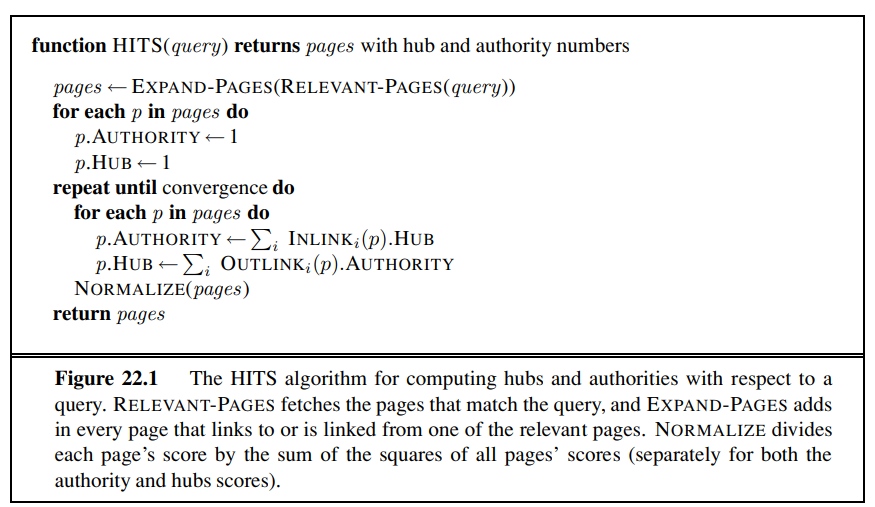

The HITS algorithm

The Hyperlink-Induced Topic Search algorithm, also known as “Hubs and Authorities” or HITS, is another influential link-analysis algorithm (see Figure 22.1). HITS differs from PageRank in several ways. First, it is a query-dependent measure: it rates pages with respect to a query. That means that it must be computed anew for each query—a computational burden that most search engines have elected not to take on. Given a query, HITS first finds a set of pages that are relevant to the query. It does that by intersecting hit lists of query words, and then adding pages in the link neighborhood of these pages—pages that link to or are linked from one of the pages in the original relevant set.

Each page in this set is considered an authority on the query to the degree that other pages in the relevant set point to it. A page is considered a hub to the degree that it points to other authoritative pages in the relevant set. Just as with PageRank, we don’t want to merely count the number of links; we want to give more value to the high-quality hubs and authorities. Thus, as with PageRank, we iterate a process that updates the authority score of a page to be the sum of the hub scores of the pages that point to it, and the hub score to be the sum of the authority scores of the pages it points to. If we then normalize the scores and repeat k times, the process will converge.

Both PageRank and HITS played important roles in developing our understanding of Web information retrieval. These algorithms and their extensions are used in ranking billions of queries daily as search engines steadily develop better ways of extracting yet finer signals of search relevance.

Question answering

Information retrieval is the task of finding documents that are relevant to a query, where the query may be a question, or just a topic area or concept. Question answering is a somewhat different task, in which the query really is a question, and the answer is not a ranked list of documents but rather a short response—a sentence, or even just a phrase. There have been question-answering NLP (natural language processing) systems since the 1960s, but only since 2001 have such systems used Web information retrieval to radically increase their breadth of coverage.

The ASKMSR system (Banko et al., 2002) is a typical Web-based question-answering system. It is based on the intuition that most questions will be answered many times on the Web, so question answering should be thought of as a problem in precision, not recall. We don’t have to deal with all the different ways that an answer might be phrased—we only have to find one of them. For example, consider the query [Who killed Abraham Lincoln?] Suppose a system had to answer that question with access only to a single encyclopedia, whose entry on Lincoln said

John Wilkes Booth altered history with a bullet. He will forever be known as the man who ended Abraham Lincoln’s life.

To use this passage to answer the question, the system would have to know that ending a life can be a killing, that “He” refers to Booth, and several other linguistic and semantic facts.

ASKMSR does not attempt this kind of sophistication—it knows nothing about pronoun reference, or about killing, or any other verb. It does know 15 different kinds of questions, and how they can be rewritten as queries to a search engine. It knows that [Who killed Abraham Lincoln] can be rewritten as the query [* killed Abraham Lincoln] and as [Abraham Lincoln was killed by *]. It issues these rewritten queries and examines the results that come back— not the full Web pages, just the short summaries of text that appear near the query terms. The results are broken into 1-, 2-, and 3-grams and tallied for frequency in the result sets and for weight: an n-gram that came back from a very specific query rewrite (such as the exact phrase match query [“Abraham Lincoln was killed by *”]) would get more weight than one from a general query rewrite, such as [Abraham OR Lincoln OR killed]. We would expect that “John Wilkes Booth” would be among the highly ranked n-grams retrieved, but so would “Abraham Lincoln” and “the assassination of” and “Ford’s Theatre.”

Once the n-grams are scored, they are filtered by expected type. If the original query starts with “who,” then we filter on names of people; for “how many” we filter on numbers, for “when,” on a date or time. There is also a filter that says the answer should not be part of the question; together these should allow us to return “John Wilkes Booth” (and not “Abraham Lincoln”) as the highest-scoring response.

In some cases the answer will be longer than three words; since the components responses only go up to 3-grams, a longer response would have to be pieced together from shorter pieces. For example, in a system that used only bigrams, the answer “John Wilkes Booth” could be pieced together from high-scoring pieces “John Wilkes” and “Wilkes Booth.”

At the Text Retrieval Evaluation Conference (TREC), ASKMSR was rated as one of the top systems, beating out competitors with the ability to do far more complex language understanding. ASKMSR relies upon the breadth of the content on the Web rather than on its own depth of understanding. It won’t be able to handle complex inference patterns like associating “who killed” with “ended the life of.” But it knows that the Web is so vast that it can afford to ignore passages like that and wait for a simple passage it can handle.

INFORMATION EXTRACTION

Information extraction is the process of acquiring knowledge by skimming a text and looking for occurrences of a particular class of object and for relationships among objects. A typical task is to extract instances of addresses from Web pages, with database fields for street, city, state, and zip code; or instances of storms from weather reports, with fields for temperature, wind speed, and precipitation. In a limited domain, this can be done with high accuracy. As the domain gets more general, more complex linguistic models and more complex learning techniques are necessary. We will see in Chapter 23 how to define complex language models of the phrase structure (noun phrases and verb phrases) of English. But so far there are no complete models of this kind, so for the limited needs of information extraction, we define limited models that approximate the full English model, and concentrate on just the parts that are needed for the task at hand. The models we describe in this section are approximations in the same way that the simple 1-CNF logical model in Figure 7.21 (page 271) is an approximations of the full, wiggly, logical model.

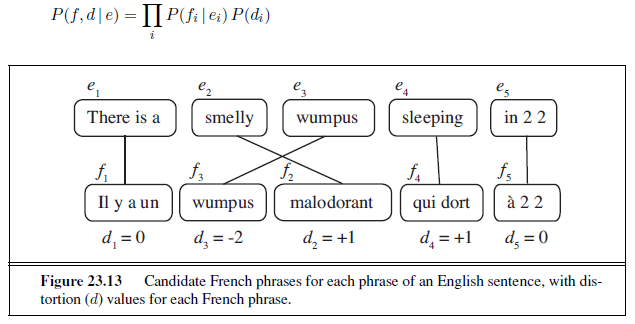

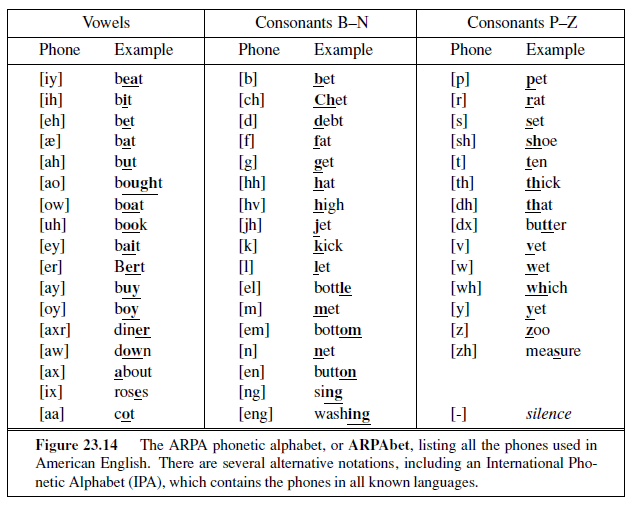

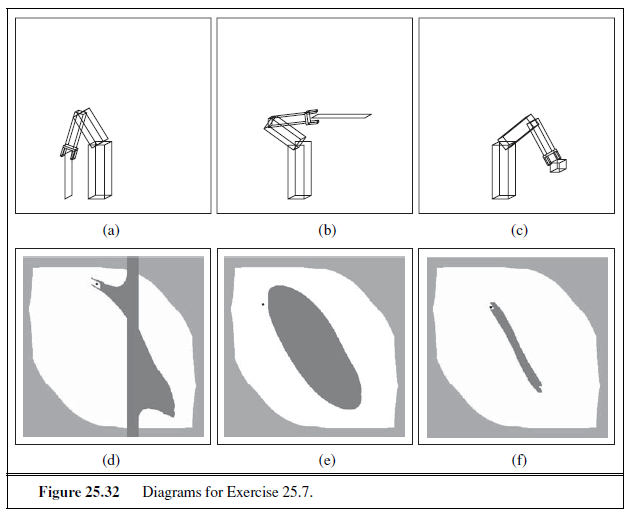

In this section we describe six different approaches to information extraction, in order of increasing complexity on several dimensions: deterministic to stochastic, domain-specific to general, hand-crafted to learned, and small-scale to large-scale.

Finite-state automata for information extraction

The simplest type of information extraction system is an attribute-based extraction system that assumes that the entire text refers to a single object and the task is to extract attributes of that object. For example, we mentioned in Section 12.7 the problem of extracting from the text “IBM ThinkBook 970. Our price: $399.00” the set of attributes { Manufacturer=IBM, Model=ThinkBook970, Price=$399.00 }. We can address this problem by defining a template (also known as a pattern) for each attribute we would like to extract. The template is defined by a finite state automaton, the simplest example of which is the regular expression, or regex. Regular expressions are used in Unix commands such as grep, in programming languages such as Perl, and in word processors such as Microsoft Word. The details vary slightly from one tool to another and so are best learned from the appropriate manual, but here we show how to build up a regular expression template for prices in dollars:

[0-9] matches any digit from 0 to 9

[0-9]+ matches one or more digits

[.][0-9][0-9] matches a period followed by two digits

([.][0-9][0-9])? matches a period followed by two digits, or nothing

[$][0-9]+([.][0-9][0-9])? matches $249.99 or $1.23 or $1000000 or . . .

Templates are often defined with three parts: a prefix regex, a target regex, and a postfix regex. For prices, the target regex is as above, the prefix would look for strings such as “price:” and the postfix could be empty. The idea is that some clues about an attribute come from the attribute value itself and some come from the surrounding text.

If a regular expression for an attribute matches the text exactly once, then we can pull out the portion of the text that is the value of the attribute. If there is no match, all we can do is give a default value or leave the attribute missing; but if there are several matches, we need a process to choose among them. One strategy is to have several templates for each attribute, ordered by priority. So, for example, the top-priority template for price might look for the prefix “our price:”; if that is not found, we look for the prefix “price:” and if that is not found, the empty prefix. Another strategy is to take all the matches and find some way to choose among them. For example, we could take the lowest price that is within 50% of the highest price. That will select $78.00 as the target from the text “List price $99.00, special sale price $78.00, shipping $3.00.”

One step up from attribute-based extraction systems are relational extraction systems,which deal with multiple objects and the relations among them. Thus, when these systems see the text “$249.99,” they need to determine not just that it is a price, but also which object has that price. A typical relational-based extraction system is FASTUS, which handles news stories about corporate mergers and acquisitions. It can read the story Bridgestone Sports Co. said Friday it has set up a joint venture in Taiwan with a local concern and a Japanese trading house to produce golf clubs to be shipped to Japan.

and extract the relations:

e∈ JointVentures ∧ Product(e, “golf clubs”) ∧Date(e, “Friday”) ∧Member(e, “Bridgestone Sports Co”) ∧Member(e, “a local concern”) ∧Member(e, “a Japanese trading house”) .

A relational extraction system can be built as a series of cascaded finite-state transducers. That is, the system consists of a series of small, efficient finite-state automata (FSAs), where each automaton receives text as input, transduces the text into a different format, and passes it along to the next automaton. FASTUS consists of five stages:

-

Tokenization

-

Complex-word handling

-

Basic-group handling

-

Complex-phrase handling

-

Structure merging

FASTUS’s first stage is tokenization, which segments the stream of characters into tokens (words, numbers, and punctuation). For English, tokenization can be fairly simple; just separating characters at white space or punctuation does a fairly good job. Some tokenizers also deal with markup languages such as HTML, SGML, and XML.

The second stage handles complex words, including collocations such as “set up” and “joint venture,” as well as proper names such as “Bridgestone Sports Co.” These are recognized by a combination of lexical entries and finite-state grammar rules. For example, a company name might be recognized by the rule

CapitalizedWord+ (“Company” | “Co” | “Inc” | “Ltd”)

The third stage handles basic groups, meaning noun groups and verb groups. The idea is to chunk these into units that will be managed by the later stages. We will see how to write a complex description of noun and verb phrases in Chapter 23, but here we have simple rules that only approximate the complexity of English, but have the advantage of being representable by finite state automata. The example sentence would emerge from this stage as the following sequence of tagged groups:

- NG: Bridgestone Sports Co.

- VG: said

- NG: Friday

- NG: it

- VG: had set up

- NG: a joint venture

- PR: in

- NG: Taiwan

- PR: with

- NG: a local concern

- CJ: and

- NG: a Japanese trading house

- VG: to produce

- NG: golf clubs

- VG: to be shipped

- PR: to

- NG: Japan

Here NG means noun group, VG is verb group, PR is preposition, and CJ is conjunction.

The fourth stage combines the basic groups into complex phrases. Again, the aim is to have rules that are finite-state and thus can be processed quickly, and that result in unambiguous (or nearly unambiguous) output phrases. One type of combination rule deals with domain-specific events. For example, the rule

Company+ SetUp JointVenture (“with” Company+)?

captures one way to describe the formation of a joint venture. This stage is the first one in the cascade where the output is placed into a database template as well as being placed in the output stream. The final stage merges structures that were built up in the previous step. If the next sentence says “The joint venture will start production in January,” then this step will notice that there are two references to a joint venture, and that they should be merged into one. This is an instance of the identity uncertainty problem discussed in Section 14.6.3.

In general, finite-state template-based information extraction works well for a restricted domain in which it is possible to predetermine what subjects will be discussed, and how they will be mentioned. The cascaded transducer model helps modularize the necessary knowledge, easing construction of the system. These systems work especially well when they are reverse-engineering text that has been generated by a program. For example, a shopping site on the Web is generated by a program that takes database entries and formats them into Web pages; a template-based extractor then recovers the original database. Finite-state information extraction is less successful at recovering information in highly variable format, such as text written by humans on a variety of subjects.

Probabilistic models for information extraction

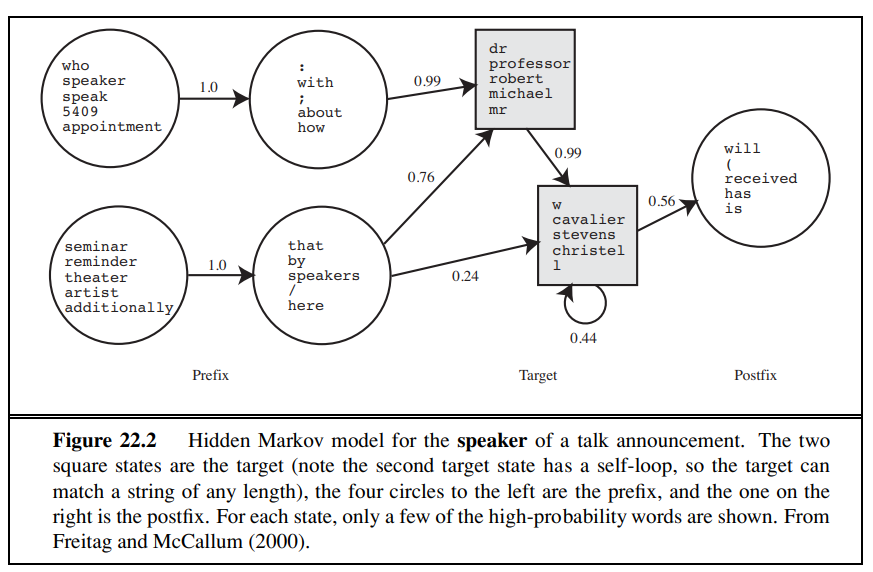

When information extraction must be attempted from noisy or varied input, simple finite-state approaches fare poorly. It is too hard to get all the rules and their priorities right; it is better to use a probabilistic model rather than a rule-based model. The simplest probabilistic model for sequences with hidden state is the hidden Markov model, or HMM.

Recall from Section 15.3 that an HMM models a progression through a sequence of hidden states, x~t~, with an observation e~t~ at each step. To apply HMMs to information extraction, we can either build one big HMM for all the attributes or build a separate HMM for each attribute. We’ll do the second. The observations are the words of the text, and the hidden states are whether we are in the target, prefix, or postfix part of the attribute template, or in the background (not part of a template). For example, here is a brief text and the most probable (Viterbi) path for that text for two HMMs, one trained to recognize the speaker in a talk announcement, and one trained to recognize dates. The “-” indicates a background state:

Text: There will be a seminar by Dr. Andrew McCallum on Friday Speaker: PRE PRE TARGET TARGET TARGET POST Date: PRE TARGET

HMMs have two big advantages over FSAs for extraction. First, HMMs are probabilistic, and thus tolerant to noise. In a regular expression, if a single expected character is missing, the regex fails to match; with HMMs there is graceful degradation with missing characters/words, and we get a probability indicating the degree of match, not just a Boolean match/fail. Second,

HMMs can be trained from data; they don’t require laborious engineering of templates, and thus they can more easily be kept up to date as text changes over time.

Note that we have assumed a certain level of structure in our HMM templates: they all consist of one or more target states, and any prefix states must precede the targets, postfix states most follow the targets, and other states must be background. This structure makes it easier to learn HMMs from examples. With a partially specified structure, the forward– backward algorithm can be used to learn both the transition probabilities P(X~t~ |X~t−1~) between states and the observation model, P(E~t~ |X~t~), which says how likely each word is in each state. For example, the word “Friday” would have high probability in one or more of the target states of the date HMM, and lower probability elsewhere.

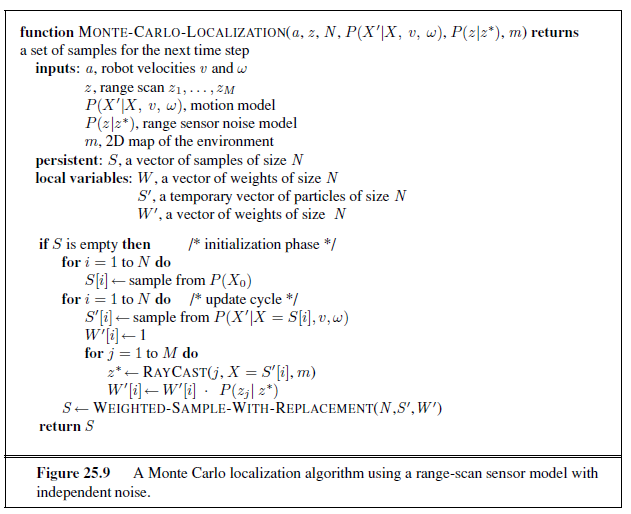

With sufficient training data, the HMM automatically learns a structure of dates that we find intuitive: the date HMM might have one target state in which the high-probability words are “Monday,” “Tuesday,” etc., and which has a high-probability transition to a target state with words “Jan”, “January,” “Feb,” etc. Figure 22.2 shows the HMM for the speaker of a talk announcement, as learned from data. The prefix covers expressions such as “Speaker:” and “seminar by,” and the target has one state that covers titles and first names and another state that covers initials and last names.

Once the HMMs have been learned, we can apply them to a text, using the Viterbi algorithm to find the most likely path through the HMM states. One approach is to apply each attribute HMM separately; in this case you would expect most of the HMMs to spend most of their time in background states. This is appropriate when the extraction is sparse— when the number of extracted words is small compared to the length of the text.

The other approach is to combine all the individual attributes into one big HMM, which would then find a path that wanders through different target attributes, first finding a speaker target, then a date target, etc. Separate HMMs are better when we expect just one of each attribute in a text and one big HMM is better when the texts are more free-form and dense with attributes. With either approach, in the end we have a collection of target attribute observations, and have to decide what to do with them. If every expected attribute has one target filler then the decision is easy: we have an instance of the desired relation. If there are multiple fillers, we need to decide which to choose, as we discussed with template-based systems. HMMs have the advantage of supplying probability numbers that can help make the choice. If some targets are missing, we need to decide if this is an instance of the desired relation at all, or if the targets found are false positives. A machine learning algorithm can be trained to make this choice.

Conditional random fields for information extraction

One issue with HMMs for the information extraction task is that they model a lot of probabilities that we don’t really need. An HMM is a generative model; it models the full joint probability of observations and hidden states, and thus can be used to generate samples. That is, we can use the HMM model not only to parse a text and recover the speaker and date, but also to generate a random instance of a text containing a speaker and a date. Since we’re not interested in that task, it is natural to ask whether we might be better off with a model that doesn’t bother modeling that possibility. All we need in order to understand a text is a discriminative model, one that models the conditional probability of the hidden attributes given the observations (the text). Given a text e1:N , the conditional model finds the hidden state sequence X1:N that maximizes P (X1:N | e1:N ).

Modeling this directly gives us some freedom. We don’t need the independence assumptions of the Markov model—we can have an x~t~ that is dependent on x1. A framework for this type of model is the conditional random field, or CRF, which models a conditional probability distribution of a set of target variables given a set of observed variables. Like Bayesian networks, CRFs can represent many different structures of dependencies among the variables. One common structure is the linear-chain conditional random field for representing Markov dependencies among variables in a temporal sequence. Thus, HMMs are the temporal version of naive Bayes models, and linear-chain CRFs are the temporal version of logistic regression, where the predicted target is an entire state sequence rather than a single binary variable.

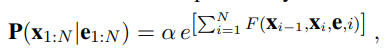

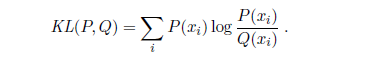

Let e1:N be the observations (e.g., words in a document), and x1:N be the sequence of hidden states (e.g., the prefix, target, and postfix states). A linear-chain conditional random field defines a conditional probability distribution:

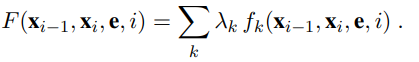

where α is a normalization factor (to make sure the probabilities sum to 1), and F is a feature function defined as the weighted sum of a collection of k component feature functions:

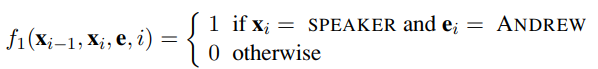

The λ~k~ parameter values are learned with a MAP (maximum a posteriori) estimation procedure that maximizes the conditional likelihood of the training data. The feature functions are the key components of a CRF. The function fk has access to a pair of adjacent states, x~i−1~ and x~i~, but also the entire observation (word) sequence e, and the current position in the temporal sequence, i. This gives us a lot of flexibility in defining features. We can define a simple feature function, for example one that produces a value of 1 if the current word is ANDREW and the current state is SPEAKER:

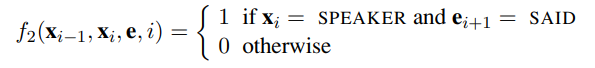

How are features like these used? It depends on their corresponding weights. If λ1 > 0, then whenever f~1~ is true, it increases the probability of the hidden state sequence x~1:N~ . This is another way of saying “the CRF model should prefer the target state SPEAKER for the word ANDREW.” If on the other hand λ~1~ < 0, the CRF model will try to avoid this association, and if λ~1~ = 0, this feature is ignored. Parameter values can be set manually or can be learned from data. Now consider a second feature function:

This feature is true if the current state is SPEAKER and the next word is “said.” One would therefore expect a positive λ~2~ value to go with the feature. More interestingly, note that both f~1~ and f~2~ can hold at the same time for a sentence like “Andrew said . . . .” In this case, the two features overlap each other and both boost the belief in x~1~ = SPEAKER. Because of the independence assumption, HMMs cannot use overlapping features; CRFs can. Furthermore, a feature in a CRF can use any part of the sequence e~1:N~ . Features can also be defined over transitions between states. The features we defined here were binary, but in general, a feature function can be any real-valued function. For domains where we have some knowledge about the types of features we would like to include, the CRF formalism gives us a great deal of flexibility in defining them. This flexibility can lead to accuracies that are higher than with less flexible models such as HMMs.

Ontology extraction from large corpora

So far we have thought of information extraction as finding a specific set of relations (e.g., speaker, time, location) in a specific text (e.g., a talk announcement). A different application of extraction technology is building a large knowledge base or ontology of facts from a corpus. This is different in three ways: First it is open-ended—we want to acquire facts about all types of domains, not just one specific domain. Second, with a large corpus, this task is dominated by precision, not recall—just as with question answering on the Web (Section 22.3.6). Third, the results can be statistical aggregates gathered from multiple sources, rather than being extracted from one specific text.

For example, Hearst (1992) looked at the problem of learning an ontology of concept categories and subcategories from a large corpus. (In 1992, a large corpus was a 1000-page encyclopedia; today it would be a 100-million-page Web corpus.) The work concentrated on templates that are very general (not tied to a specific domain) and have high precision (are almost always correct when they match) but low recall (do not always match). Here is one of the most productive templates:

NP such as NP (, NP)* (,)? ((and | or) NP)? .

Here the bold words and commas must appear literally in the text, but the parentheses are for grouping, the asterisk means repetition of zero or more, and the question mark means optional. NP is a variable standing for a noun phrase; Chapter 23 describes how to identify noun phrases; for now just assume that we know some words are nouns and other words (such as verbs) that we can reliably assume are not part of a simple noun phrase. This template matches the texts “diseases such as rabies affect your dog” and “supports network protocols such as DNS,” concluding that rabies is a disease and DNS is a network protocol. Similar templates can be constructed with the key words “including,” “especially,” and “or other.” Of course these templates will fail to match many relevant passages, like “Rabies is a disease.” That is intentional. The “NP is a NP” template does indeed sometimes denote a subcategory relation, but it often means something else, as in “There is a God” or “She is a little tired.” With a large corpus we can afford to be picky; to use only the high-precision templates. We’ll miss many statements of a subcategory relationship, but most likely we’ll find a paraphrase of the statement somewhere else in the corpus in a form we can use.

Automated template construction

The subcategory relation is so fundamental that is worthwhile to handcraft a few templates to help identify instances of it occurring in natural language text. But what about the thousands of other relations in the world? There aren’t enough AI grad students in the world to create and debug templates for all of them. Fortunately, it is possible to learn templates from a few examples, then use the templates to learn more examples, from which more templates can be learned, and so on. In one of the first experiments of this kind, Brin (1999) started with a data set of just five examples:

(“Isaac Asimov”, “The Robots of Dawn”)

(“David Brin”, “Startide Rising”)

(“James Gleick”, “Chaos—Making a New Science”)

(“Charles Dickens”, “Great Expectations”)

(“William Shakespeare”, “The Comedy of Errors”)

Clearly these are examples of the author–title relation, but the learning system had no knowledge of authors or titles. The words in these examples were used in a search over a Web corpus, resulting in 199 matches. Each match is defined as a tuple of seven strings,

(Author, Title, Order, Prefix, Middle, Postfix, URL) ,

where Order is true if the author came first and false if the title came first, Middle is the characters between the author and title, Prefix is the 10 characters before the match, Suffix is the 10 characters after the match, and URL is the Web address where the match was made.

Given a set of matches, a simple template-generation scheme can find templates to explain the matches. The language of templates was designed to have a close mapping to the matches themselves, to be amenable to automated learning, and to emphasize high precision (possibly at the risk of lower recall). Each template has the same seven components as a match. The Author and Title are regexes consisting of any characters (but beginning and ending in letters) and constrained to have a length from half the minimum length of the examples to twice the maximum length. The prefix, middle, and postfix are restricted to literal strings, not regexes. The middle is the easiest to learn: each distinct middle string in the set of matches is a distinct candidate template. For each such candidate, the template’s Prefix is then defined as the longest common suffix of all the prefixes in the matches, and the Postfix is defined as the longest common prefix of all the postfixes in the matches. If either of these is of length zero, then the template is rejected. The URL of the template is defined as the longest prefix of the URLs in the matches.

In the experiment run by Brin, the first 199 matches generated three templates. The most productive template was

- Title by Author URL: www.sff.net/locus/c

The three templates were then used to retrieve 4047 more (author, title) examples. The examples were then used to generate more templates, and so on, eventually yielding over 15,000 titles. Given a good set of templates, the system can collect a good set of examples. Given a good set of examples, the system can build a good set of templates.

The biggest weakness in this approach is the sensitivity to noise. If one of the first few templates is incorrect, errors can propagate quickly. One way to limit this problem is to not accept a new example unless it is verified by multiple templates, and not accept a new template unless it discovers multiple examples that are also found by other templates.

Machine reading

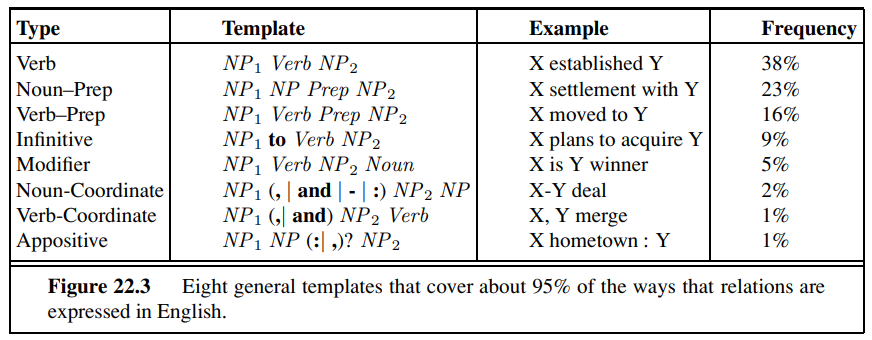

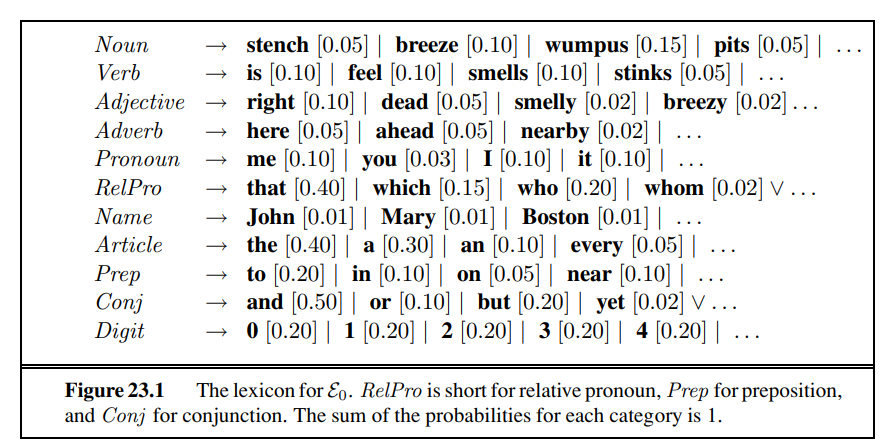

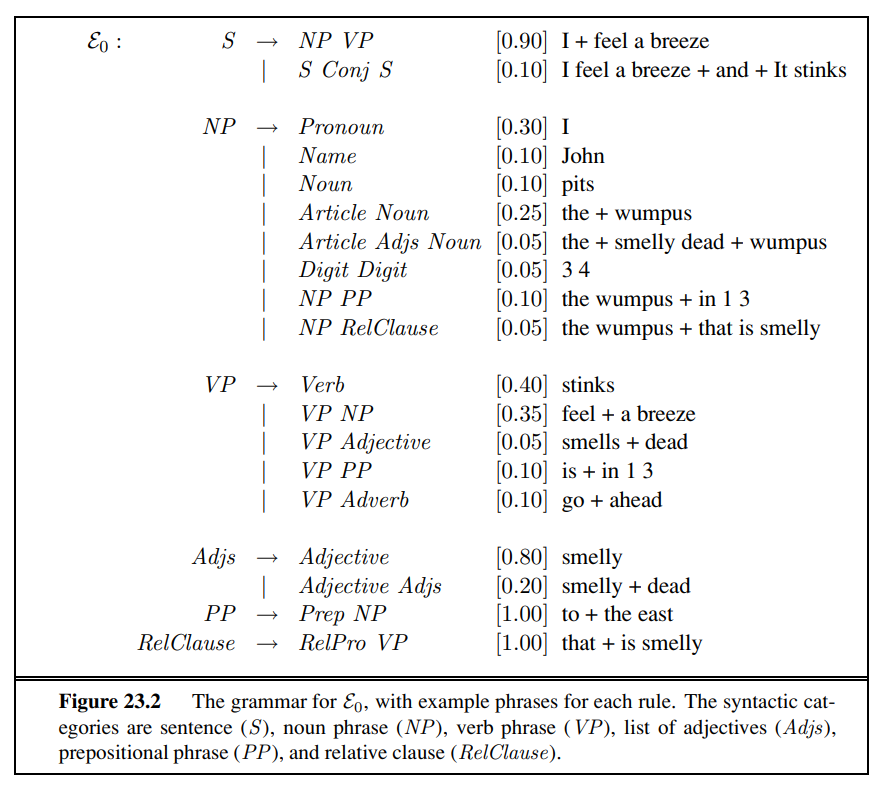

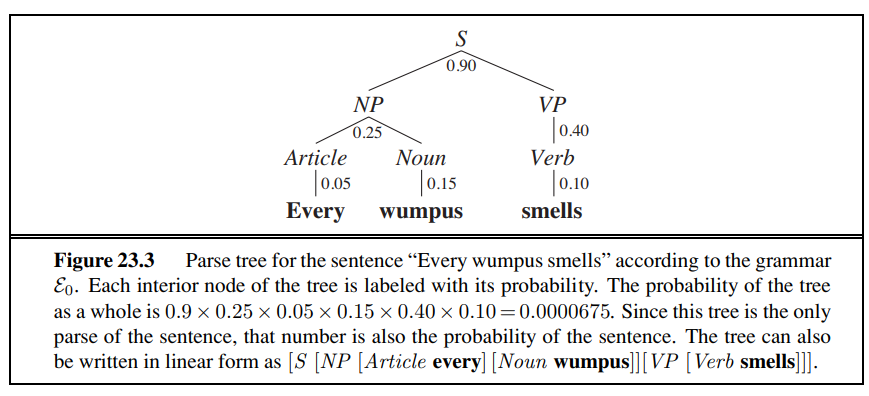

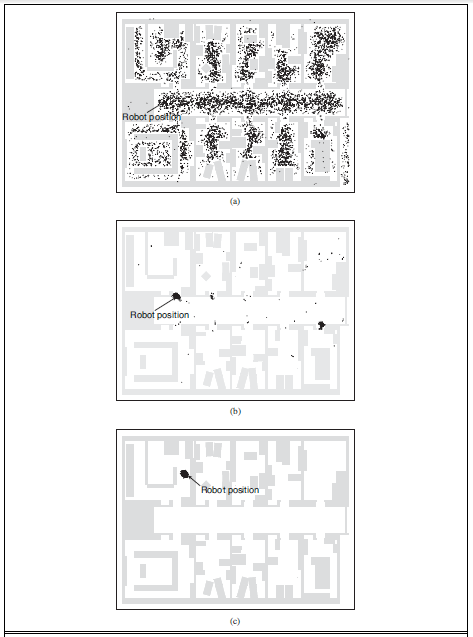

Automated template construction is a big step up from handcrafted template construction, but it still requires a handful of labeled examples of each relation to get started. To build a large ontology with many thousands of relations, even that amount of work would be onerous; we would like to have an extraction system with no human input of any kind—a system that could read on its own and build up its own database. Such a system would be relation-independent; would work for any relation. In practice, these systems work on all relations in parallel, because of the I/O demands of large corpora. They behave less like a traditional informationextraction system that is targeted at a few relations and more like a human reader who learns from the text itself; because of this the field has been called machine reading.A representative machine-reading system is TEXTRUNNER (Banko and Etzioni, 2008). TEXTRUNNER uses cotraining to boost its performance, but it needs something to bootstrap from. In the case of Hearst (1992), specific patterns (e.g., such as) provided the bootstrap, and for Brin (1998), it was a set of five author–title pairs. For TEXTRUNNER, the original inspiration was a taxonomy of eight very general syntactic templates, as shown in Figure 22.3. It was felt that a small number of templates like this could cover most of the ways that relationships are expressed in English. The actual bootsrapping starts from a set of labelled examples that are extracted from the Penn Treebank, a corpus of parsed sentences. For example, from the parse of the sentence “Einstein received the Nobel Prize in 1921,” TEXTRUNNER is able to extract the relation (“Einstein,” “received,” “Nobel Prize”). Given a set of labeled examples of this type, TEXTRUNNER trains a linear-chain CRF to extract further examples from unlabeled text. The features in the CRF include function words like “to” and “of” and “the,” but not nouns and verbs (and not noun phrases or verb phrases). Because TEXTRUNNER is domain-independent, it cannot rely on predefined lists of nouns and verbs.

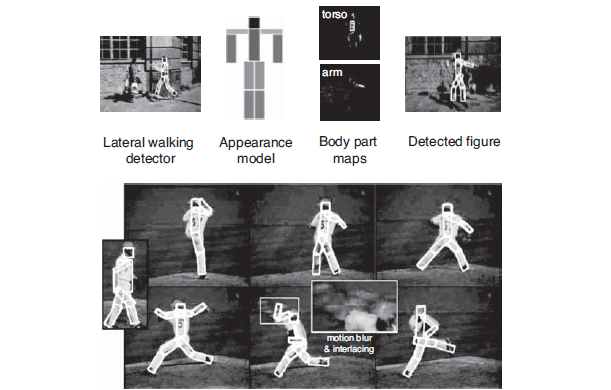

Type Template Example Frequency

TEXTRUNNER achieves a precision of 88% and recall of 45% (f~1~ of 60%) on a large Web corpus. TEXTRUNNER has extracted hundreds of millions of facts from a corpus of a half-billion Web pages. For example, even though it has no predefined medical knowledge, it has extracted over 2000 answers to the query [what kills bacteria]; correct answers include antibiotics, ozone, chlorine, Cipro, and broccoli sprouts. Questionable answers include “water,” which came from the sentence “Boiling water for at least 10 minutes will kill bacteria.” It would be better to attribute this to “boiling water” rather than just “water.”

With the techniques outlined in this chapter and continual new inventions, we are starting to get closer to the goal of machine reading.

SUMMARY

The main points of this chapter are as follows:

Probabilistic language models based on n-grams recover a surprising amount of information about a language. They can perform well on such diverse tasks as language identification, spelling correction, genre classification, and named-entity recognition.

These language models can have millions of features, so feature selection and preprocessing of the data to reduce noise is important.

Text classification can be done with naive Bayes n-gram models or with any of the classification algorithms we have previously discussed. Classification can also be seen as a problem in data compression.

Information retrieval systems use a very simple language model based on bags of words, yet still manage to perform well in terms of recall and precision on very large corpora of text. On Web corpora, link-analysis algorithms improve performance.

Question answering can be handled by an approach based on information retrieval, for questions that have multiple answers in the corpus. When more answers are available in the corpus, we can use techniques that emphasize precision rather than recall.

Information-extraction systems use a more complex model that includes limited notions of syntax and semantics in the form of templates. They can be built from finitestate automata, HMMs, or conditional random fields, and can be learned from examples.

In building a statistical language system, it is best to devise a model that can make good use of available data, even if the model seems overly simplistic.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL NOTES

N -gram letter models for language modeling were proposed by Markov (1913). Claude Shannon (Shannon and Weaver, 1949) was the first to generate n-gram word models of English. Chomsky (1956, 1957) pointed out the limitations of finite-state models compared with context-free models, concluding, “Probabilistic models give no particular insight into some of the basic problems of syntactic structure.” This is true, but probabilistic models do provide insight into some other basic problems—problems that context-free models ignore. Chomsky’s remarks had the unfortunate effect of scaring many people away from statistical models for two decades, until these models reemerged for use in speech recognition (Jelinek, 1976).

Kessler et al. (1997) show how to apply character n-gram models to genre classification, and Klein et al. (2003) describe named-entity recognition with character models. Franz and Brants (2006) describe the Google n-gram corpus of 13 million unique words from a trillion words of Web text; it is now publicly available. The bag of words model gets its name from a passage from linguist Zellig Harris (1954), “language is not merely a bag of words but a tool with particular properties.” Norvig (2009) gives some examples of tasks that can be accomplished with n-gram models.

Add-one smoothing, first suggested by Pierre-Simon Laplace (1816), was formalized by Jeffreys (1948), and interpolation smoothing is due to Jelinek and Mercer (1980), who used it for speech recognition. Other techniques include Witten–Bell smoothing (1991), Good– Turing smoothing (Church and Gale, 1991) and Kneser–Ney smoothing (1995). Chen and Goodman (1996) and Goodman (2001) survey smoothing techniques.

Simple n-gram letter and word models are not the only possible probabilistic models. Blei et al. (2001) describe a probabilistic text model called latent Dirichlet allocation that views a document as a mixture of topics, each with its own distribution of words. This model can be seen as an extension and rationalization of the latent semantic indexing model of (Deerwester et al., 1990) (see also Papadimitriou et al. (1998)) and is also related to the multiple-cause mixture model of (Sahami et al., 1996).

Manning and Schütze (1999) and Sebastiani (2002) survey text-classification techniques. Joachims (2001) uses statistical learning theory and support vector machines to give a theoretical analysis of when classification will be successful. Apté et al. (1994) report an accuracy of 96% in classifying Reuters news articles into the “Earnings” category. Koller and Sahami (1997) report accuracy up to 95% with a naive Bayes classifier, and up to 98.6% with a Bayes classifier that accounts for some dependencies among features. Lewis (1998) surveys forty years of application of naive Bayes techniques to text classification and retrieval. Schapire and Singer (2000) show that simple linear classifiers can often achieve accuracy almost as good as more complex models and are more efficient to evaluate. Nigam et al. (2000) show how to use the EM algorithm to label unlabeled documents, thus learning a better classification model. Witten et al. (1999) describe compression algorithms for classification, and show the deep connection between the LZW compression algorithm and maximum-entropy language models.

Many of the n-gram model techniques are also used in bioinformatics problems. Biostatistics and probabilistic NLP are coming closer together, as each deals with long, structured sequences chosen from an alphabet of constituents.

The field of information retrieval is experiencing a regrowth in interest, sparked by the wide usage of Internet searching. Robertson (1977) gives an early overview and introduces the probability ranking principle. Croft et al. (2009) and Manning et al. (2008) are the first textbooks to cover Web-based search as well as traditional IR. Hearst (2009) covers user interfaces for Web search. The TREC conference, organized by the U.S. government’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), hosts an annual competition for IR systems and publishes proceedings with results. In the first seven years of the competition, performance roughly doubled.

The most popular model for IR is the vector space model (Salton et al., 1975). Salton’s work dominated the early years of the field. There are two alternative probabilistic models, one due to Ponte and Croft (1998) and one by Maron and Kuhns (1960) and Robertson and Sparck Jones (1976). Lafferty and Zhai (2001) show that the models are based on the same joint probability distribution, but that the choice of model has implications for training the parameters. Craswell et al. (2005) describe the BM25 scoring function and Svore and Burges (2009) describe how BM25 can be improved with a machine learning approach that incorporates click data—examples of past search queies and the results that were clicked on.

Brin and Page (1998) describe the PageRank algorithm and the implementation of a Web search engine. Kleinberg (1999) describes the HITS algorithm. Silverstein et al. (1998) investigate a log of a billion Web searches. The journal Information Retrieval and the proceedings of the annual SIGIR conference cover recent developments in the field.

Early information extraction programs include GUS (Bobrow et al., 1977) and (DeJong, 1982). Recent information extraction has been pushed forward by the annual Message Understand Conferences (MUC), sponsored by the U.S. government. The FASTUS finite-state system was done by Hobbs et al. (1997). It was based in part on the idea from Pereira and Wright (1991) of using FSAs as approximations to phrase-structure grammars. Surveys of template-based systems are given by Roche and Schabes (1997), Appelt (1999), and Muslea (1999). Large databases of facts were extracted by Craven et al. (2000), Pasca et al. (2006), Mitchell (2007), and Durme and Pasca (2008).

Freitag and McCallum (2000) discuss HMMs for Information Extraction. CRFs were introduced by Lafferty et al. (2001); an example of their use for information extraction is described in (McCallum, 2003) and a tutorial with practical guidance is given by (Sutton and McCallum, 2007). Sarawagi (2007) gives a comprehensive survey.

Banko et al. (2002) present the ASKMSR question-answering system; a similar system is due to Kwok et al. (2001). Pasca and Harabagiu (2001) discuss a contest-winning question-answering system. Two early influential approaches to automated knowledge engineering were by Riloff (1993), who showed that an automatically constructed dictionary performed almost as well as a carefully handcrafted domain-specific dictionary, and by Yarowsky (1995), who showed that the task of word sense classification (see page 756) could be accomplished through unsupervised training on a corpus of unlabeled text with accuracy as good as supervised methods.

The idea of simultaneously extracting templates and examples from a handful of labeled examples was developed independently and simultaneously by Blum and Mitchell (1998), who called it cotraining and by Brin (1998), who called it DIPRE (Dual Iterative Pattern Relation Extraction). You can see why the term cotraining has stuck. Similar early work, under the name of bootstrapping, was done by Jones et al. (1999). The method was advanced by the QXTRACT (Agichtein and Gravano, 2003) and KNOWITALL (Etzioni et al., 2005) systems. Machine reading was introduced by Mitchell (2005) and Etzioni et al. (2006) and is the focus of the TEXTRUNNER project (Banko et al., 2007; Banko and Etzioni, 2008).

This chapter has focused on natural language text, but it is also possible to do information extraction based on the physical structure or layout of text rather than on the linguistic structure. HTML lists and tables in both HTML and relational databases are home to data that can be extracted and consolidated (Hurst, 2000; Pinto et al., 2003; Cafarella et al, 2008).

The Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) holds regular conferences and publishes the journal Computational Linguistics. There is also an International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING). The textbook by Manning and Schütze (1999) covers statistical language processing, while Jurafsky and Martin (2008) give a comprehensive introduction to speech and natural language processing.

EXERCISES

22.1 This exercise explores the quality of the n-gram model of language. Find or create a monolingual corpus of 100,000 words or more. Segment it into words, and compute the frequency of each word. How many distinct words are there? Also count frequencies of bigrams (two consecutive words) and trigrams (three consecutive words). Now use those frequencies to generate language: from the unigram, bigram, and trigram models, in turn, generate a 100word text by making random choices according to the frequency counts. Compare the three generated texts with actual language. Finally, calculate the perplexity of each model.

22.2 Write a program to do segmentation of words without spaces. Given a string, such as the URL “thelongestlistofthelongeststuffatthelongestdomainnameatlonglast.com,” return a list of component words: [“the,” “longest,” “list,” . . .]. This task is useful for parsing URLs, for spelling correction when words runtogether, and for languages such as Chinese that do not have spaces between words. It can be solved with a unigram or bigram word model and a dynamic programming algorithm similar to the Viterbi algorithm.

22.3 (Adapted from Jurafsky and Martin (2000).) In this exercise you will develop a classifier for authorship: given a text, the classifier predicts which of two candidate authors wrote the text. Obtain samples of text from two different authors. Separate them into training and test sets. Now train a language model on the training set. You can choose what features to use; n-grams of words or letters are the easiest, but you can add additional features that you think may help. Then compute the probability of the text under each language model and chose the most probable model. Assess the accuracy of this technique. How does accuracy change as you alter the set of features? This subfield of linguistics is called stylometry; itsSTYLOMETRY

successes include the identification of the author of the disputed Federalist Papers (Mosteller and Wallace, 1964) and some disputed works of Shakespeare (Hope, 1994). Khmelev and Tweedie (2001) produce good results with a simple letter bigram model.

22.4 This exercise concerns the classification of spam email. Create a corpus of spam email and one of non-spam mail. Examine each corpus and decide what features appear to be useful for classification: unigram words? bigrams? message length, sender, time of arrival? Then train a classification algorithm (decision tree, naive Bayes, SVM, logistic regression, or some other algorithm of your choosing) on a training set and report its accuracy on a test set.

22.5 Create a test set of ten queries, and pose them to three major Web search engines. Evaluate each one for precision at 1, 3, and 10 documents. Can you explain the differences between engines?

22.6 Try to ascertain which of the search engines from the previous exercise are using case folding, stemming, synonyms, and spelling correction.